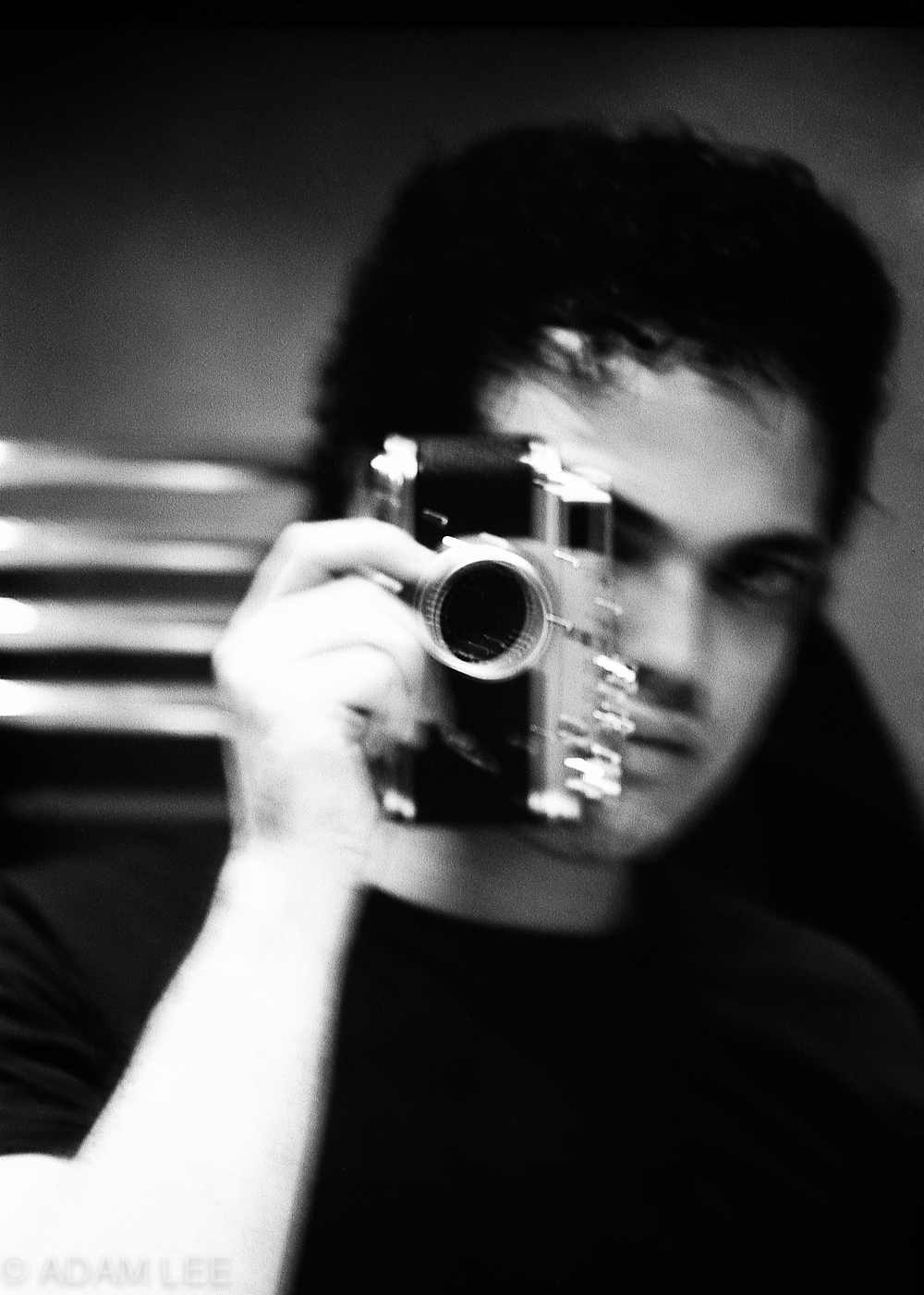

Adam Lee is a man of many parts. Not content with his upcoming PhD in biology, he is a very talented musician and a self-made expert on photography. At the age of 25, this accomplished young man is making a big name for himself through his music and his undoubted photographic skills.

Today my friend George James and I interviewed Adam over drinks at the wonderful Timber Yard cafe, opposite Red Dot Cameras in Old Street, London, both regular haunts. George had met Adam earlier in the year at a Leica Meet in Mayfair and had been vastly impressed with his photography and by his palpable enthusiasm for film cameras. The fact that there was a nice Leica M4 in the scene did no harm: Any old Leica will get George’s attention.

So, after a delay of several months, it was time to find out a bit more about a photographer of whom, I am sure, we will hear a lot about in the future. The M4 (which was dropped and dented in the meantime) has been replaced by a 1957 double-stroke M3 which, Adam says, is the best film camera ever made. I’m not about to argue because I love my 1954 version of the same camera. Currently Adam is using a Soviet-era Jupiter 50mm as his main lens but he had a mint 1961 Leitz 90mm Elmar tucked away in his bag. He loves the bokeh on that surprisingly compact medium tele.

In a short time Adam has become an expert on the M3. He has even dismantled the camera and discovered how to adjust the shutter speeds when he realised they were out of kilter. He put his music and audio skills to work in a rather unconventional way―recording the shutter release at all speeds and then analysing the results digitally until he had the camera absolutely spot on.

He is now firmly in love with the M3 which is in excellent condition except for a couple of tears in the leatherette. He is about to get a kit and tackle the replacement of the body trim himself, not a task for the faint of heart. He is also a firm fan of the earlier double-stroke film advance lever on his M3. I was curious about this because many Leica fans prefer the later single-stroke. The story goes that Leica engineers were worried that one quick advance might lead to torn film and introduced the two-step operation to help minimise the danger. As it happens, their worries proved unfounded, so a single-stroke film advance was introduced in in March 1958.

Adam believes the two-step advance is better and has even discovered something George and I didn’t know: That the first stroke, or half-cock as it were, actually locks the shutter and prevents an inadvertent release. He has learned that we can make a virtue out of a delaying tactic introduced by Leica when the M3 came on the scene in 1954.

A few years ago the photographic world was about to write off film cameras. As a result one after another company ceased production. Leica is now the only serious manufacturer of traditional 35mm cameras–the automatic M7 and the more traditional manual MP. Yet, in a complete reversal of fortunes, film is making a big comeback. And this resurgence isn’t led by older photographers revisiting their roots. On the contrary, it is a new breed of young enthusiasts such as Adam Lee which is rediscovering the merits of film.

Film is so much more versatile and satisfying to work with than digital, maintains Adam. Film renders tone in completely different way to digital—a more logarithmic approach rather than the linear treatment of modern sensors, he says. The result, suggests Adam, is a smoother gradient and a more satisfying and vibrant image. He is amused that digital camera manufacturers and fans often refer to “film-like qualities” as a sort of holy grail. Why, he wonders, do they not simply use film.

Film buffs do their own processing, of course, and Adam has equipped his bathroom as a darkroom. He says that often at three o’clock in the morning a red light can be seen seeping under the door of the en-suite as he takes the opportunity to work without fear of interruption. He has taught himself the intricacies of developing and printing. He has also perfected his scanning techniques, using an Epson V600 and regularly produces 18MP digital images from his negatives. As for choice of film, he is currently on a monochrome kick and loves Kodak Tri-X. But he really prefers Fuji Neopan 400 for its overall excellent in black-and-white rendering.

Going back to film from digital does need a tad more discipline. For one thing, it isn’t feasible to click away as we now do with digital. With 36 exposures at your disposal there is a natural tendency to be more selective, waiting for the right moment and taking greater care. This is no bad thing. There is also the complete lack of recorded metadata, something digital fans have come to rely on to remind them about past sessions, including exposure, aperture, speed, ISO and, even, the lens fitted to the camera. With film there is none of this and I have to admit I find it a problem. It is also an irritation when using manual lenses, such as M lenses, on modern non-Leica digitals. Many times I completely forget what lens I had attached on a particular day.

Impressively, Adam has embraced these shortcomings and manages to take copious notes as he goes along, mainly using his iPhone in a nod to modernity. Along the way he has built up an admirable knowledge about film lore, even to the extent of being able to put us old hands to shame on several occasions. He has now embarked on a series of YouTube tutorials on film and this is his first and quite remarkable effort.

Adam is well placed to vlog on photography because he already has a very successful music video channel with millions of views. With his engaging personality and ease of delivery I feel sure his photography videos will soon get the same level of hits.

There is little doubt that Adam will make a big impression on the photography world as he develops his skills and gains followers through his YouTube channels and his presence on other social media (follow him @AdamLeeGuitar and view his work on Flickr). But his portfolio of work speaks for his talent. Both George and I are mightily impressed with Adam’s work and his talent can only get better as he develops over the years.