When Mike Evans asked if I would like to try out the review 50mm Zeiss Touit it seemed like too good an opportunity to miss. In 20-20 hindsight the best film SLR I ever owned—twice, as it happened—was the Contax RX. A technological tour de force for its time, it sat below the theoretically more robust ST and the bomb-proof RTSIII in the then Kyocera-owned lineup. I had a full complement of Carl Zeiss lenses to go with it —Biogons, Planars, a tremendous 85mm Sonnar that was so sharp I shaved with it for a while, and even a brace of fantastically heavy Vario-Sonnars that I christened “Gustav” and “Dora” (well it amused me at the time).

I also had a foray into the G Series, with a G1 (adapted to take the 35mm f/2 when it came out) and a G2, which was well ahead of its time and deserved to sell a lot better than I suspect it did. Over time, however, I returned to Leica M for most uses and transitioned to Nikon when Contax ceased to exist. All was quiet for me on the Oberkochen optical front for a while (a Zeiss Age…?) until, towards the end of my film Leica M days I chose to pair an a là carte MP4 .85 with a 50mm Sonnar and a 35mm Biogon—and fell in love all over agaiin.

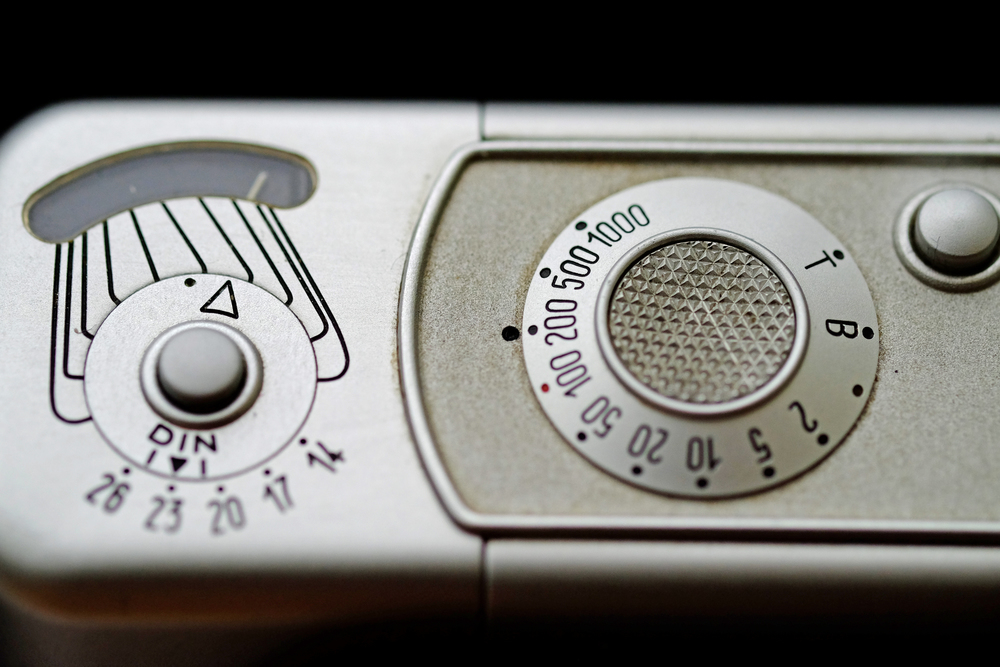

It’s the bokeh, you see. Or don’t see. If you see what I mean. When I first started in photography, back in those pre-internet days when we did most of our learning from books and other people, bokeh was an alien concept—well, foreign.

The idea that something you couldn’t actually see per se could become a significant compositional tool only really dawned on me when I started to use that fast Zeiss glass. I came to realise that the areas of an image that are not in sharp focus are as important in telling the overall story as the subject itself. It’s a slippery slope from then on, as you start craving the next optical fix of creamy out of focus goodness. You start to seek out lenses with ever shallower depth of focus, ever more rounded aperture blades.

Bigger front elements

The good stuff is expensive, of course, and as you slip further into the madness you may even start lying to your loved ones about the cost of feeding your habit. You start to rationalise—all lenses look the same to a non-photographer, don’t they?—and hope that your wife doesn’t notice your front elements getting bigger and bigger. You may even find yourself trying some of the really rough gear —lenses from the former Soviet Union—with bokeh so crunchy it makes you feel somehow… grubby…

I’ll stop waffling. As I type I’ve just completed a week on the Island of Madeira accompanied by my X-Pro2 and, for comparison, both the Touit and my own Fujinon XF 60mm f2.4 R. Side by side the two lenses could not look more different, belying their 10mm variance in focal length and slight (.4) difference in maximum aperture. The Fuji is one of the original Fujinon trio of 28, 35 and 60mm lenses that first saw the light of day at the same time as the X-Pro1 and it shows. I can’t help feeling that we will see it refreshed or even replaced in the not too distant future. It is physically smaller than the Zeiss, with a deeply recessed front element and a very wide, finely milled focussing ring that acts as a magnet to grease and dust. it has an “old-school” demeanour that would not have drawn attention if it dropped through a wormhole and found itself in 1976.

The Touit, by comparison, looks like it dropped through a wormhole from 2046. It is streamlined to a degree that makes me wonder if wind-tunnel testing was part of the design process. The aperture and focus rings are set flush with the body and are rubberised in what is once again an irritatingly dust and grease-attracting manner. Both lenses have deep, bayonet hoods that increase overall length considerably. Experience has shown that the Fujinon can safely be used hood-free due to the aforementioned deep-set front element but the Zeiss does not encourage such cavalier disregard for flare and I used it with the hood throughout.

Magnification

There are two other significant variances to mention and both are important, albeit for different reasons. The Zeiss scores over the Fujinon in terms of magnification, delivering a true 1:1 without the aid of fiddly extension rings. It also features an internal focusing mechanism which keeps overall physical lens length a constant and at least leads one to believe that it is better sealed than the Fuji, albeit not claiming to be weatherproof.

So. My cunning plan was to press into service some of Madeira’s famed biodiversity and to run the two in parallel to provide direct comparison shots of flowers and the like. I managed that—up to a point. What I hadn’t accounted for was the extent to which the Touit would end up bolted to the front of my X-Pro2 as my walkabout lens for most of the week. It’s the combination of a focal length that at a pinch could pass for a long standard and the ability to focus to infinity one minute and on a gnat’s nadgers the next that makes the Touit such a compelling proposition and useful travel lens.

A case in point is the Mercado de Lavadores in Funchal. A thriving market that is still very much the hub of fresh produce in the city, it sells a range of goods from fruit and vegetables to cut flowers and hats. It also has an fish market that helps you to find the location from a couple of streets away. The light is variable at best, from shafts of sunlight via fluorescent strips to stygian shade. The Touit was more than up to the job. I found the slightly less tight angle of view more useful while switching quickly from general photography to close-up and the lens really shone in the fish market as I stared down at finned things that certainly weren’t guppies, laying out on piles of Zeiss—sorry ice.

Swinging podule

I followed the market with an inadvertent ride in a cable-car up to Monte Palace and the botanical gardens that tumble down the hillside from the top. I say inadvertent because I certainly had not planned to spend twenty minutes in a swinging podule, rising up into the clouds. Once there, however, I decided to make the most of it and entered the gardens with lens at the ready.

Two hours later, footsore and largely shot out I found my way out and started my descent. I hadn’t really thought it through, either in terms of how high I had risen or the topography of Funchal’s road system. In most places, roads wind up and down steep inclines, meandering through a series of turns to level out the angle of descent. Not here. Monte is famous for their two-man toboggans —a hair-raising ride downhill in a glorified wicker basket, steered, propelled and occasionally braked by two gentlemen clinging to the back. I hadn’t intended to partake myself, but equally I hadn’t realised that it was just as hazardous making one’s way down, sharing the same roads that run straight down the hillside. The toboggans are largely silent, save for the occasional whimper from a terrified tourist, and it is not easy to keep oneself alert to rapidly approaching 4-man shopping baskets when one’s own toes are being mashed to a pulp in one’s shoes by the steepness of the descent. Still my frequent rest-stops offered the opportunity to use the Touit as a lens to capture fast-moving action.

In optical terms, as my images attest, there is little to choose between the two lenses in terms of quality. Both are capable of turning in a decent performance at normal shooting distances as well as within their respective macro performance parameters. The Zeiss coatings deliver a slightly warmer result, and the bokeh is a little more creamy, particularly at short focussing distances but the Fujinon is no slouch in that department itself. Both lenses suffer from a similar flaw—an occasional hesitancy to focus upon a small subject in close up, with a “busy” background a few feet behind, a tall flower head in a larger bed, for instance. I tend to shoot with a relatively small focus area set and it was frustrating to have to take three or four goes on occasion to lock on, particularly in overcast, relatively low-contrast conditions. The Fujinon does this every so often but the Zeiss far more frequently, at least for my liking. Both would benefit from a three-way focus-limiter switch, say <1m, off and >1m, to make both the lens and the photographer have to work a little less hard at times.

Mixed feelings

I’ll give the Touit back with mixed feelings. I really appreciate the Fujinon 60mm and it is definitely one of those lenses that has been given a new lease of life by the 24mp sensor of the X-Pro2. It is a grand portrait lens and remarkably compact for its capabilities. It will be the perfect big sister to the 35mm f/2 when it sees the light of day shortly, giving me once again a compact and eminently workable 35-50-90 (oh alright, 23-35-60) “holy trinity” travel set.

But. With the 50mm Touit in my lineup I might just be tempted to leave the 35 at home and go out and about with just the compact 23 and the capable 50; an even lighter two-lens set that could, let’s be honest, take on 90% of my travel shooting.

Food for thought… Mike, do we have to give it back…?

Thanks for a great review. I have also been thinking of 23/2 35/1.4 50/2 but I also relise i rarely use the 50 mm equiv FL. As you say 23/ 50 macro is a lively lightweight package with weatheproof and macro options