The Battle of Imphal-Kohima, 1944

The year 2014 marked the centenary of the start of the First World War. It was also the 70th anniversary of one of the most historic World War II battles fought far from the Western Front. It was a war so few knew much about that the men who fought in it called themselves the ‘Forgotten Army’.

“The year is 1944. The place Imphal, capital of Manipur, a remote and inaccessible State on the north-east frontier of India; a beauty spot and the last place on earth likely to suffer the horrors of modern war. But here was fought the most fiercely contested battle of the Burma Campaign, the battle which, if for no reason, will go down in history as the greatest military disaster ever suffered by the Japanese on land.” ‘Imphal–A Flower on Lofty Hills’, Lt-Gen Sir Geoffrey Evans and Antony Brett-James

Context

Following the retreat from Burma of the British and Indian forces in 1942, the Fourteenth Army under General William Slim organised its divisions in the Imphal plain. The plan was to fight the Japanese Imperial Army here under conditions that favoured the British and stretched thin the Japanese lines of communication. The battles that followed were fought around this perimeter in the thick jungle of the hills and the few approaches by road, flanked on either side by paddy fields. On 19 March 1944, the Japanese 15th and 31st Divisions clashed with the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade at Sangshak in the first of many fiercely fought battles for Imphal.

Through the months March to July 1944, the battles raged on simultaneously over several fronts. The monsoon rains turned the difficult terrain into formidable obstacles for both sides and presented a definite hazard to aircraft carrying relief and supplies to the forward troops.

Photographs

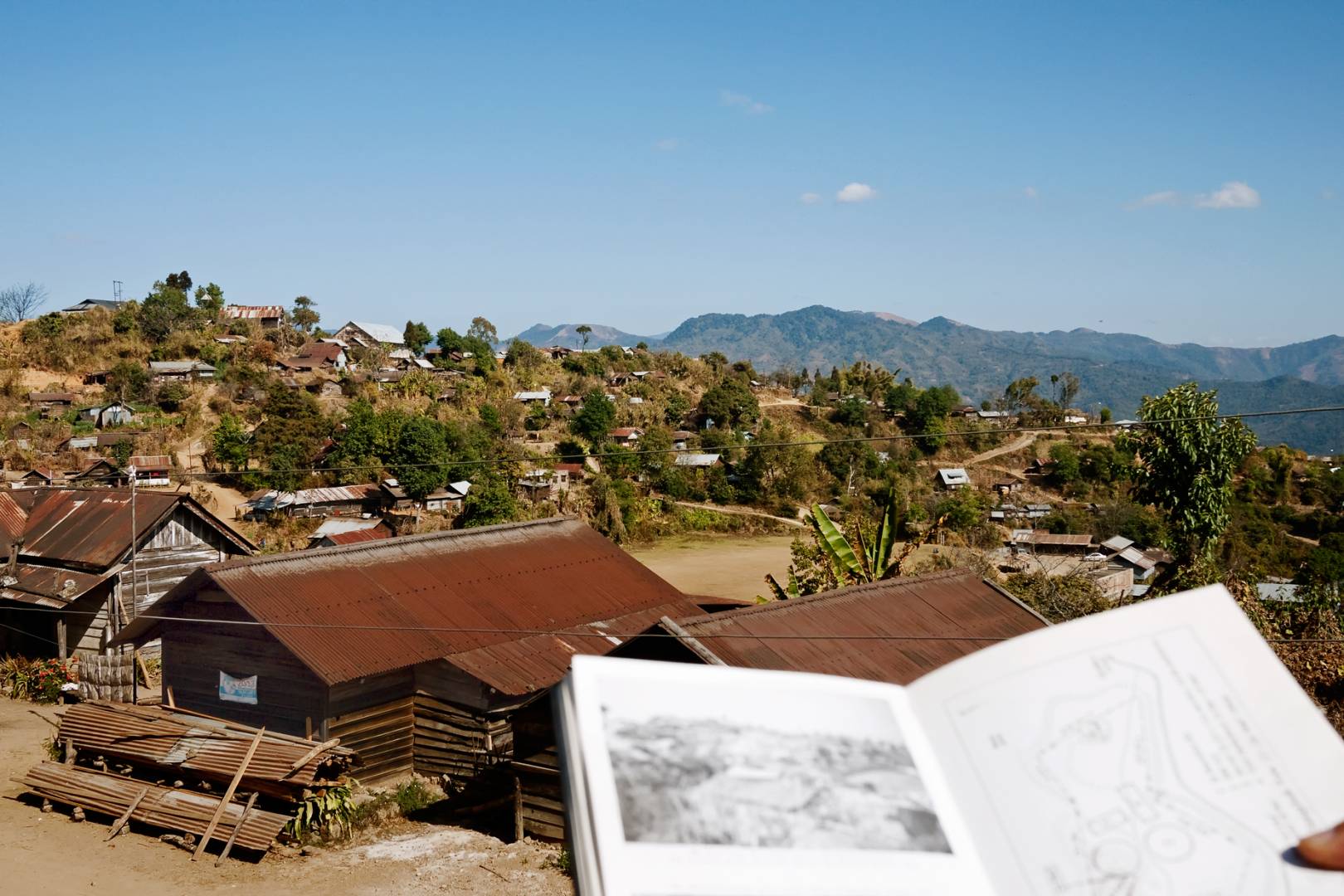

Much of the countryside outside Imphal remains unchanged seventy-five years after the end of the war. In the southeast, on the Tamu-Palel road, nature has repossessed the hills of the Shenam Saddle. Scraggy, Gibraltar, Recce Hill and all the others are thick with trees and undergrowth once again. But the slit trenches dug by the soldiers are still in evidence. In Sangshak, in the northeast spoke, the village has a new church but the football field is the same. The sun still beats down fiercely on the paddy fields, the rice stalks dry and dusty before the rains, as they were at the Battle of Nungshigum in the Iril River valley. And the turel still runs through Ningthukhong on the Tiddim Road.

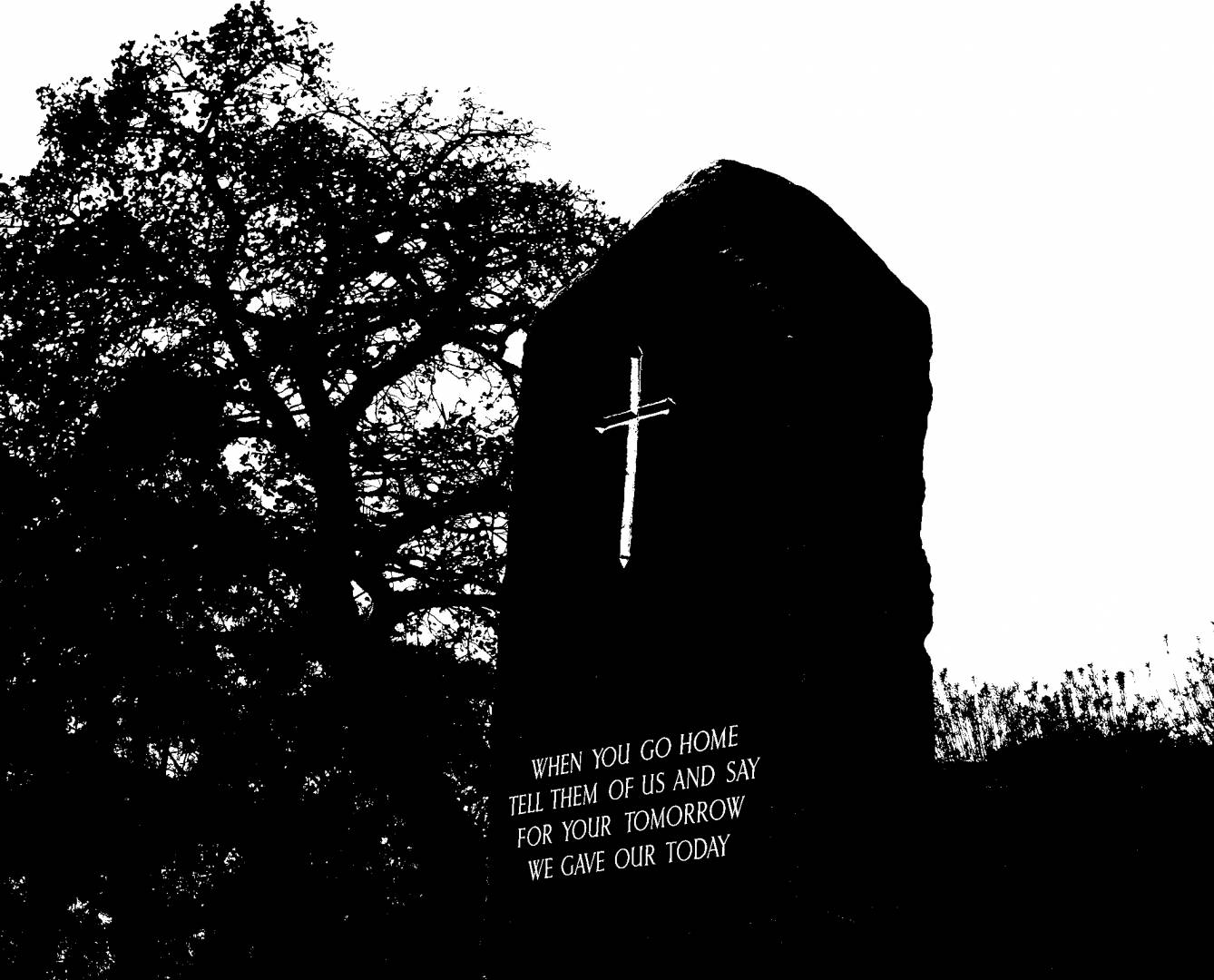

Habitation, however, has changed Kohima. It has completely obliterated any battlefield scars on Garrison Hill, Kuki Piquet, FSD or DIS Hills. On the site of the District Commissioner’s Bungalow, a Commonwealth War Graves cemetery now stands, a sombre spot in the heart of the city.

Everywhere, life goes on. Kids walk to school, play in the streets. Men and women go about their daily work in the fields and businesses.

The battlefields, as they are today, and the signs of life present everywhere are the subjects of these photographs.

In this open hall, near the memorial, a painting depicts British officials who visited the site immediately after the bombing.

On the 20th of April, 1943, in a prelude to what was to come, Japanese planes bombed this site, killing over ninety civilians gathered here. A memorial in Khurai Thangjam Leikai is dedicated to their memory.

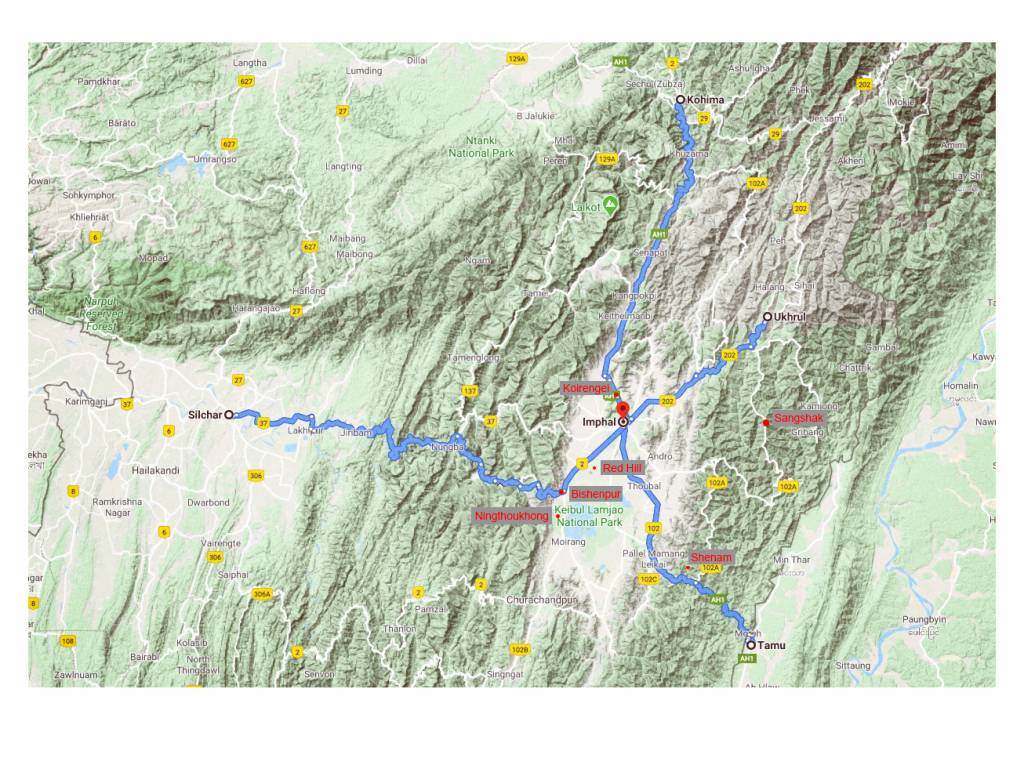

The Imphal plain is the only large expanse of flat ground in the great stretch of mountains between India and Burma. The Fourteenth Army concentrated 4 Corps in its 1,500 square kilometre expanse.

Similar to the points of a compass, six routes converged at the plain to meet at Imphal: From the north, the Kohima road and the path down the Iril River Valley, from the north-east, the Ukhrul road, from the south-east, the Tamu-Palel road, from the south, the Tiddim road and from the west, the Silchar-Bishenpur track.

It was by these routes that the Japanese fought to break into the plain. The offensive began on 6 March 1944.

”Though few believed it at the time,” writes Frank Owen1, “here in the ‘Bloody Plain’ the spine of the Japanese Imperial Army in South-east Asia was broken.” We Gave Our Today: Burma 1941-1945, William Fowler2

Koirengei / Imphal Main was one of three all-weather airfields along the Imphal-Kohima road in the Imphal valley. It had great strategic importance to the British and Indian troops for receiving supplies and reinforcements during the Battle of Imphal 1944 against the advancing Japanese.

“Every road, airfield, and camp had to be made from virgin jungle or rice field. The whole of the labour, many thousands, was Indian, and much of it came from the Indian Tea Association, which organised, officered, and controlled some forty thousand of its own workers. Without this contribution we should never have built either roads or the airfields that were vital for the Burma campaign and for the supply of China.” — ‘Defeat into Victory”, Field Marshal Viscount Slim

In March 1944, Sangshak, a Naga village situated on a hilltop north-east of Imphal, was at the centre of fierce combat between the British, Indian and Gurkha troops and the Japanese army in a bid to control the Ukhrul Road that led to Imphal and Kohima.

“The men of the 153rd Battalion’s C Company were positioned on the extreme south-western edge of the plateau where it declined in a shallow curve round to the south. They had a perfect field of fire westwards across the slopes of West Hill and southwards across a pint-sized football field – the only one in the Naga Hills, on the only patch of flat ground between Sangshak village and the defenders’ perimeter. This was the way the enemy was expected, and indeed arrived, in the last rapidly fading light of the afternoon.” — ‘The Battle at Sangshak’, Harry Seaman 3

“It speaks volumes for the determination and tenacity of the Japanese battalion that, even in the face of so disastrous a start, as soon as darkness fell they mounted a second assault — this time from the south, across the tiny football pitch. This had its anxious moments for the Gurkhas. This night attack continued for some hours, but was broken off long before dawn, when another twenty bodies were found scattered around the football pitch.” — ‘The Battle at Sangshak’, Harry Seaman 3

“The fate of the Empire depends on this battle. You will capture Imphal but you will be annihilated.” — Commander of the Japanese 15th Army, in an order to the troops of the 33rd Division.

Nungshigum has two peaks rising almost 4,000 feet above sea level. Its steep slopes are covered in long grass and shrubs, above grow a number of trees while at the base it is surrounded by dried-up paddy fields. In bright sunshine, it is a picturesque stretch of countryside.

This is how it was at the Battle of Nungshigum that took place on April 7, 1944. A battalion of the Japanese 51st Regiment occupied the vital Nungshigum Ridge, which overlooked the main airstrip at Imphal, posing a major threat to 4 Corps concentrated in the plain.

As the sun beat down fiercely on the fighting that ensued to flush out the Japanese it marked the first time the British Army used tanks in such steep terrain. The sharp incline the M3 Lee tanks had to negotiate had tragic consequences as two squadrons of Carabiniers lost almost all their tank commanders to Japanese snipers as they stood exposed in their turrets while they directed their tank drivers.

British troops fighting the Japanese in the cluster of hills between the villages of Shenam and Tengnoupal, along the Tamu-Palel Road, quickly gave the hills nicknames—Gibraltar, Malta, Scraggy, Recce Hill, Crete West, Crete East and Nippon Hill. Collectively they made up the Shenam Saddle.

“They are hills unknown to the outside world, but they will remain always in the memories of those who fought there. They were the scene of some of the most ferocious fighting of the whole war, and hundreds and hundreds of British, Indian, Gurkha and Japanese soldiers lost their lives on these hills which changed hands time and again as counter-attack followed attack. At the outset clothed with jungle, they became completely bare except for shattered tree stumps.” — ‘Imphal–A Flower on Lofty Heights’, Evans and Brett-James

A view of part of the 5,000 ft. high Shenam Saddle from the top of Recce Hill. Malta is on the left, Gibraltar on the right and Nippon Hill in the far distance. The Japanese names for them were Yajima, Laimatol and Maejima respectively.

“I said: ‘What’s going to happen now?”’ ‘Well, it’s hard to say. I expect they’ll be over the top of the hill here in a minute.’” — Neil Gilliam’s4 record of his conversation with a company commander on Shenam Saddle

“It was the scene of intense fighting during the Japanese drive along the Palel road towards Imphal in April 1944. The position was a labyrinth of bunkers; trees were reduced to shattered trunks and the hillsides turned into barren wastes by artillery fire. The result was a field of battle reminiscent of the worst fighting on the Somme during World War One.” — National Army Museum

“The fighting went on relentlessly and on the night of May 20-21 in driving rain an attack was launched against a feature known as Red Hill in the 17 Division area near Bishenpur by men of the 2/214 Regimental Group, 33 Division. A force of 500 infantry, 100 gunners with three light-calibre guns supported by 40 sappers. It would be the closest the Japanese got to Imphal. They were stopped by a platoon of D Company 10 Baluch Regiment who held the hill under the heroic leadership of Subedar Ghulam Yasmin. The feature was known as Red Hill because shell fire had stripped away the vegetation and exposed the red laterite earth below.” – ‘We Gave Our Today: Burma 1941-1945’, William Fowler.

During April and June 1944, Ningthoukhong was the scene of many a battle, and, along with Shenam, it probably received more shelling than any other area in Burma or Assam.

The turel (stream) which flowed down from the hills and under the road proved a severe obstacle to British tanks.

It was near this small turel that runs through the village at Ningthoukhong that two Victoria Crosses were awarded in June 1944.

“A great deal of the most intense and costly fighting during the next two months took place along the dozen miles of the Silchar track between Bishenpur in the plain and the suspension bridge formerly spanning the Leimatok. This jeep track of earth and red laterite wound between and around hill features, of which some were covered with scrub or jungle, some with soft soil or boulders, while others again had a bare surface.” ‘Imphal — A Flower on Lofty Heights‘, Evans and Brett-James

In May 1944, the Japanese launched several air attacks on Bishenpur, a village south of Imphal on the Tiddim Road. The village of Potsangbam, nicknamed ‘Pots and Pans’ by the British soldiers, witnessed heavy fighting between the 17th Indian Division, the 32 Brigade of the 20th Indian Division and the Japanese 33rd Division. The Japanese supply route stretched all the way from Tiddim in Burma and then by mules along the Thangjing range.

“Before the battle at Potsangbam, we lay up all night on the edge of the paddy. At dawn the whole place was covered in mist. We were all tapped on the shoulder, ‘Come on up.’ One said, ‘Good luck,’ and we moved on to the paddy and lined up, on one side the Gurkhas, and further along another battalion. We had walked for quite a while and then the Jap guns began to open up.” — ‘Forgotten Voices of Burma: The Second World War’s Forgotten Conflict’, Julian Thompson5

On 8 April 1944, the Japanese attack on the DC’s bungalow began. British and Indian troops took up positions on the western edge of the tennis court situated on the Kohima ridge, the Japanese held its eastern edge. The battle that followed would be one of the bloodiest in the Battle of Kohima.

On the far horizon, demarcated by a row of white buildings, lies the famous Palel airfield. In 1944, Palel served as an all-weather airfield near the foothills at the southeast edge of the Imphal plain. During the days of fighting to control the Tamu-Palel road, on the night of 28 April 1944, the Indian National Army6 commander believed he could win over the loyalties of the Indian and Gurkha soldiers at Palel airfield and invited them to come across to his side. The Indian Army troops responded by opening fire on the INA battalion forcing them to flee leaving behind their weapons and ammunition.

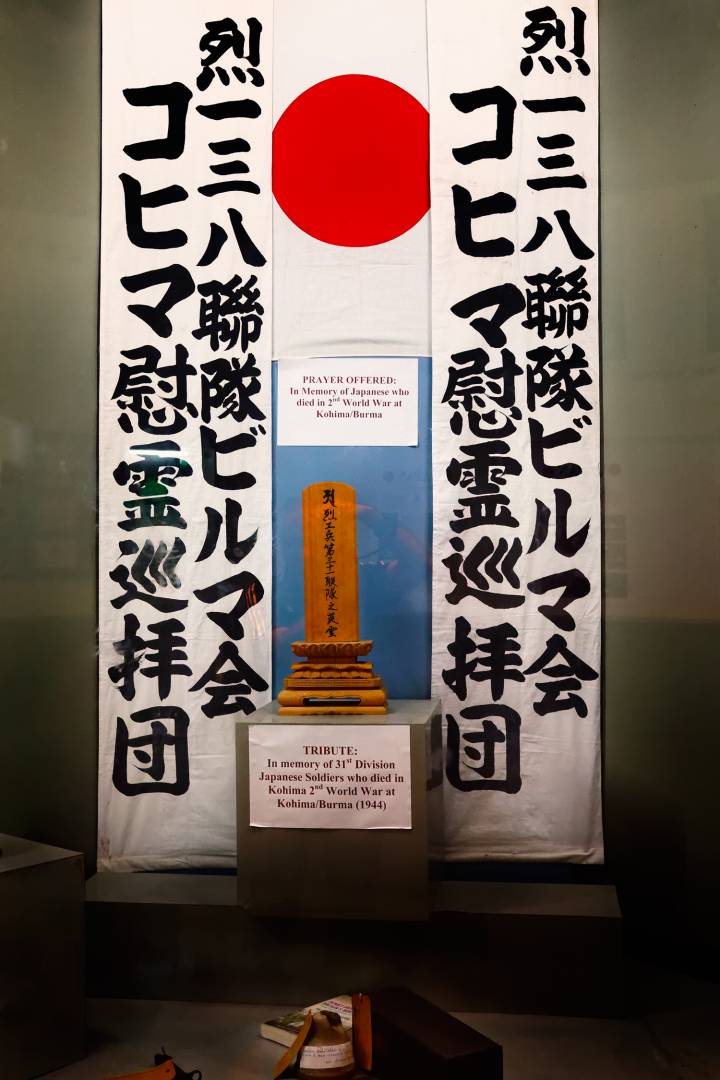

On the Imphal-Kohima road, the last and most important of the Imphal spokes, the Japanese 31st Division cut the road north of Imphal on 30 March 1944. Three months would pass before it could be re-opened. On 22 June, the tanks of 2 Division met the leading infantry of 5 Division at Milestone 109 and a convoy could go through, bringing the siege of Imphal to an end.

“There was much to dislike and despise about the way the Japs conducted the war, but no one who actually fought them on the battlefield could deny their courage and fighting prowess. For a week they had dug in and held that position under constant artillery and mortar fire, with no reinforcements nor supply of food or ammunition, and no succour for their wounded.

“In the 1990s, the All Burma Veteran Association of Japan, the equivalent of our Burma Star Association, with the support of the Japanese Government, obtained permission of the Indian Government to erect a memorial at Imphal, in memory of all the 190,000 Japanese dead in the whole Burma Campaign. The site chosen for this memorial was Red Hill, the nearest point to Imphal that the Japanese ever reached.” – ‘Battle Tales from Burma, John Randle7

This Japanese War Memorial lies at the base of Red Hill, the site of fierce fighting between Indian & British forces and the Japanese army in May 1944. It was as Robert Lyman noted in his book ‘Japan’s Last Bid for Victory: The Invasion of India, 1944’, “one of the main turning-point battles of the entire war”.

No more deaths. The Imphal War Cemetery in Imphal originally had 950 graves of Commonwealth soldiers from Britain, Australia, Canada, India, Africa and Burma. It has grown to 1,600 graves.

The Sangshak War Memorial in Lungshang is erected in memory of the men and women who fell in the Battle of Sangshak, 19-26 March 1944.

“Many a British and Indian soldier owes his life to the naked, headhunting Naga, and no soldier of the Fourteenth Army who met them will ever think of them but with admiration and affection.” — ‘Defeat into Victory’, Field Marshall Viscount Slim

“This M3 Grant tank fought at the Battle of Kohima, April–May 1944 as part of 2nd Infantry Division whose wish it is that it should remain where it stands as a permanent memorial to those who gave their lives in the defence of freedom.” — From a plaque at the site

“In one sector, only the width of the town’s tennis court separated the two sides.” — National Army Museum

“In memory of the men of the 2nd Division who fell in the Battle of Kohima and the fighting for the Imphal road April 1944–June 1944.” — From the plaque at the site

Hemant Singh Katoch and Yaiphaba Kangjam were my battlefield guides over two trips to Imphal and Kohima in 2014. This was my first introduction to the north-east. Just a year earlier, in 2013, the National Army Museum had by vote declared the Battle of Imphal and Kohima as Britain’s greatest battle. In the months leading up to and following my trips, I studied up on the Burma Campaign and, in particular, the battle of Imphal and Kohima. In this article, I have tried to describe events as far as possible in my own words but when I have failed, and there have been many times, I have relied on the voices from the past of the men who were there.

All images ©Farhiz Karanjawala. May not be reproduced without permission.

More articles by Farhiz Karanjawala

A passage to India Mark II: Fifteen years on, many changes — John Shingleton

- Frank Owen was a British journalist, author, and Member of Parliament. During World War II, he served with the Royal Tank Regiment and later with South East Asia Command. He is the author of several books including The Campaign in Burma (1946). ↩

- William Fowler was an editor of Defence magazine. He served with British forces in the Gulf War. ↩

- Harry Seaman fought with the Gurkhas at Sangshak. ↩

- An entertaining account of the conversation between Neil Gilliam and the company commander is recounted at https://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?f=46&t=87898 ↩

- Julian Thompson served in the Royal Marines, retiring as Major General. He is the author of The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Burma 1942-1945. ↩

- The Indian National Army (INA) under Subhas Chandra Bose formed an alliance with Imperial Japan in the latter’s campaign in the Southeast Asian theatre of World War II. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IndianNationalArmy) ↩

- Brigadier John Randle OBE MC was a former soldier who saw action in Burma during World War II. ↩

My father served in the RAF Operations room at Imphal but said very little about it. It was only very late in his life that one or two episodes from his experience came to light. I’ve had to read about the campaign since his death and I have two contrasting emotions. That I should have asked my father more about Imphal before he died and that I had to respect his desire not to speak about it. He’ll always be my hero for that.

Great article and well written.

My father was in Burma with RAF 237 Squadron. He never spoke about it and I have a mass of photographs taken in Burma a lot of which I have no idea where or even who some of the people are in them ,

Reading articles like these gives me insight into my fathers time there and the horrible conditions they all suffered.

Thank you .

Great article, Farhiz.

Wonderful account of a corner of the War that often gets little attention beyond the Airlift over the Hump and Chennaults Flying Tigers.

And excellent images as well.

Jason.

Thanks, Jason. Glad you liked it.

Thank you Farhiz, I appreciated your story telling and the way you brought the voices of the past to us.

What a wonderful story of a long forgotten battle. The bravery, the wonder, and just those amazing vignettes that allow us to glimpse in to what must have been a horrific situation on all involved.

Your images show the area as it is today well, in wonderful colour.

Thank you for this insightful piece.

Dave

Thank you Farhiz for this evocative historical journey. By coincidence, two of Michael’s Macfilos correspondents are already booked to travel up river into the Nagaland region later this year. So more images to come.

Well that is excellent. They should ensure that they have the required travel documents for the state. Indian citizens need an Inner Line Permit (ILP) and some ID to travel to Nagaland. Foreigners will need a Restricted Area Permit and ID, but they should check this with their agent. For one trip I flew into Imphal, Manipur and went up to Kohima by road, for the second trip I flew into Dibrugarh, Assam and entered Nagaland by road heading to Mon. In a future article for Mike I’ll recount my friendly encounter with the Assam Rifles station commander at the Naga border.

Thank you guys! To be honest, I’m relieved to find that the topic has struck a chord with you. Mike will attest to my doubts on that. Many thanks to him too for all his help through the drafting process.

All the photographs were taken with my Panasonic GF1 and 20mm (40 mm-e) lens. Even with an electronic viewfinder attached it’s a very small camera.

Read this WOW WOW WOW,THANK YOU HAD UNCLE USED TO PILOT ON THE BURMA RUN TO CHINA. WHICH CAMERA LENS COMBO YOU USE, REALLY GORGEOUS PHOTOS.

Beautifully written and photographed. Congratulations. Many of us have not forgotten this field of battle, we have never heard of it. Thank you for this introduction.

I had two uncles who fought in the Burma campaign. They also came from Northamptonshire, which featured on one of the graves shown in your story. Very interesting to imagine events so long ago over enduring landscapes you show us today. Well done.

In the 1990’s Slim’s campaign was studied as course material at the U.S. Army War College.

A wonderful article Farhiz. We, westerners often forget what happened in the east during the war. Visiting India Gate a few years back only gave me a hint of what the various conflicts were. I love the image of children the Silshar-Bishenpur track. These children are our future. Looking forward to more of your contributions on Macfilos. Incidentally what camera did you use?

Thanks for sharing

OMG,,PEAKED AHEAD SAW THE SUBJECT WENT BONKERS, THIS AREA WW2 has never gotten the press it should have had. Saving this for tonight on way to my camp upstate NY now 130ish afternoon at seven tonight will settle in front of fire and drink silent salute to these brave men! Thank you.