Assam is the gateway to many of the north-eastern states of India. On our way to one of them, our drive from the airport in Guwahati to the first night-stop at a jungle camp took a little over six hours, which includes stops along the way to stretch our legs but also because it was a Thursday. In towns and villages all over the north-east, certain days and spots are reserved as market days. In some places, meat and poultry are kept separate from the fruit and vegetables. Thursday is market day in Guwahati.

A nice surprise

At the foothills of the Himalayas, Eco Camp Nameri is situated on the fringes of Nameri National Park in Assam and along the Jia Bhorelli that flows down from Arunachal Pradesh on its way to join the Brahmaputra. The area, home to over 350 bird species, attracts birders from all parts of the country to trek its forests and raft the Bhorelli.

The itinerary for my trip had indicated ‘basic amenities’ as the description for the accommodation at the Eco Camp. By now I knew enough of the standard of accommodation in the north-east to temper my expectations. But I am pleasantly surprised as the thatched tents and attached baths turn out to be more than satisfactory. There’s even a frog to keep me company while I shave.

The Bihu girls of Nameri

On the way, we are waylaid by a party of girls dressed in colourful chadors, a traditional Assamese Bihu festival attire, who with customary charm succeed in extracting a tidy sum to add to their Bihu kitty. The Bihu festival is celebrated by the Assamese to coincide with the farming calendar.

The one we find ourselves in the middle of, called Rongali Bihu, is in the Baisakh season or the spring festival in mid-April. Two other Bihu festivals are also celebrated with traditional gusto — in January and October.

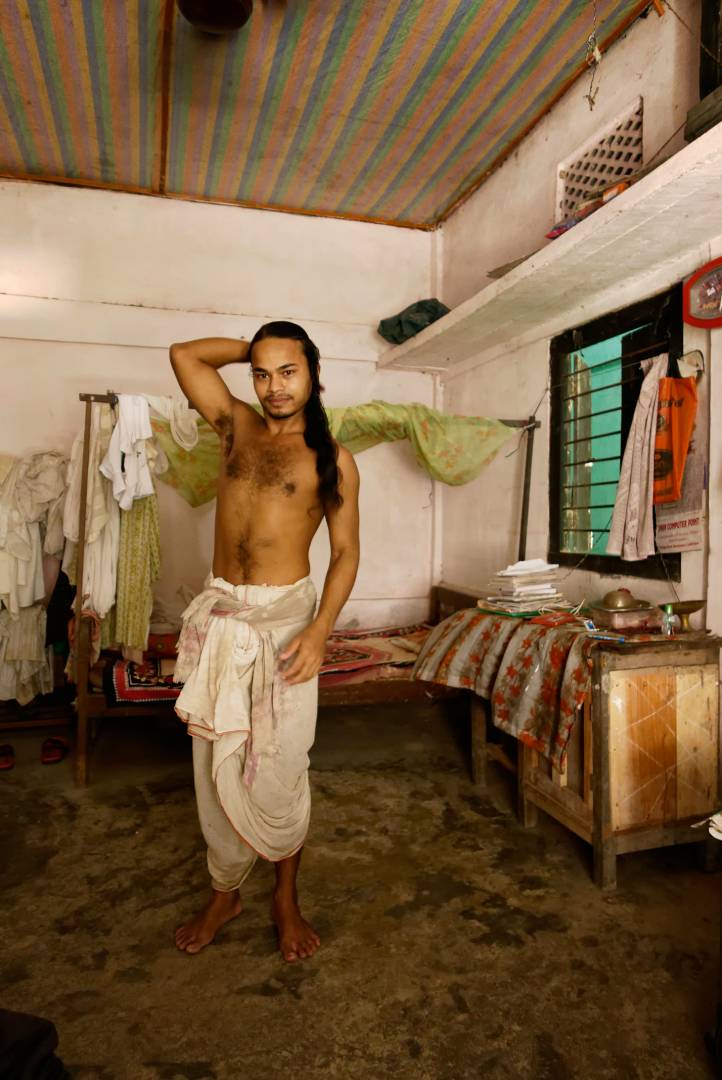

As there is still light upon reaching camp we decide to walk to the nearest Mishing tribal village. The Mishing was originally a hill tribe now settled in the plains along the Brahmaputra. The huts are all raised on stilts — a reminder of the rains and flooding season — and built of wood, bamboo and thatch. Like many north-east homes, they have a long room at the front with partitions between smaller rooms at the back. In the village, Bihu celebrations are in full swing.

There’s one aspect of rural India that stands out for me and that is the hospitality of its people. I suspect that this is true with rural communities everywhere. We are welcomed with open arms to join in the festivities.

The rhythmic beats of a dhol can be heard from a clearing behind a hut. We’re led with much fuss and cheer to the small knot of people gathered there. The dhol is loud over a distance, at close quarters it is deafening.

The dhol is a drum made of wood and hide. It is a key instrument used in a Bihu dance. Our dhol player uses a stick in one hand and the palm and fingers of his other hand to beat out a rhythm.

Wrapped around his dhol is a white cloth with a simple border much like an ugon. I don’t see any sign of the pepa, a hornpipe, or gogona, a type of vibrating reed, nor for that matter, any sign of the toka, banhi or hutuli all popular Bihu musical instruments.

There are at least five forms of Bihu dance, some performed exclusively by women, some only at night, and some performed under a tree. The one we witness is called Husori and is performed in the village courtyard.

As the dhol settles into its rhythm, the women start to sway and move in a circle, singing all the time. Dressed simply, they display spirit and energy in their dancing. It is a while before we can say our goodbyes and return to camp.

The mighty Brahmaputra

Later the same year I travelled through Assam again. My night-stop this time was on Majuli, the largest river island on the Brahmaputra, in the world. Ferries that ply to and fro have to constantly battle against soil erosion and shifting ghats. Planks laid across the gap between mud bank and deck allow cars, motorbikes, bicycles and passengers aboard.

Those lucky to find a seat sit on benches in the hold, others, like us, clamber on top of the wheelhouse. Unlike some of the other public transport, ferries generally keep to a timetable. Whenever possible we try to take the first one across at around half past eight in the morning. Since the crossing takes a little over an hour that gives us time to see the island.

There’s an oft-repeated quote about the Brahmaputra that goes: “If you cross the mighty river once, you’re destined to cross it again.”

Seems accurate in my case. Chugging across the Brahmaputra in a rickety wooden boat heaving with vehicles and passengers is an experience not to be missed despite the hazards that go with it. Besides the odd ferry capsizing, recently a ferry lost its way from Majuli to Nimati ghat with 250 passengers and vehicles on board. I believe, the passengers raised quite a commotion.

Majuli

Majuli covers an area in excess of 350 square kilometres and has a population of over 160,000. Not an island in the traditional sense, of a single landmass surrounded by water, it is made up of several islets formed by the Brahmaputra and its tributaries. The island inhabitants are mainly tribals from the Mishing and Deori tribes related to the Mongols from Burma. The water and land have a big influence on their culture and traditions.

The Vaishnavites

Majuli is the centre of Vaishnavite culture going back centuries. Vaishnavism is a Hindu philosophy whose followers take Vishnu, the preserver and protector of the universe, as their god in his many forms. Vaishnavite centres of learning and culture in Majuli are called satras. Here disciples are initiated in the traditions of Vaishnavism, which aims at reforming society through art, music and drama.

Leaving our shoes near the gate we enter one of the satras. The Uttar Kamalabari Satra is a centre for art, culture and classical studies. Like all satras it has a prayer hall and sleeping quarters for bhakts or disciples.

The mask makers

Mask making is a tradition still practised in Majuli’s satras — Samaguri Satra being the best known. Used in religious dance and drama performances to depict gods and demons, Samaguri receives orders for its masks from all parts of the country.

Led into a room which doubles as a display and demonstration hall, I recognise a Ravana and several Hanuman masks. We get an impromptu demonstration of a type of mask called lotokai mukha. These masks have moveable parts for the mouth and eyes unlike typical mukhas or face masks. There was even a bor mukha, a life-size mask, in one corner.

Bamboo, cow dung, clay, gum and cloth are the simple materials that go into making a mask. Red, yellow and indigo colours are applied with a brush made of cat or goat hair.

The Kumhars

Salmora village in Majuli is keeping another tradition alive — handmade pottery. The potter communities, known as Kumhars, are concentrated in the south-eastern area of the island where a particular type of clay soil, or kumhar mitti, is found.

Being a labour-intensive occupation, the whole family is involved in the making and distribution of clay pots and utensils. A lot of the labour force is made up of the womenfolk. The clay pots are sold or bartered for paddy to the surrounding villages. We bought ourselves some pots and did our best to keep them from breaking on the journey ahead.

Onward Journeys

A long drive and a night-stop lay ahead before our final destination, Ziro in Arunachal Pradesh. Back at the guesthouse, another traveller was also about to continue on her journey back home to Spain on a bicycle; a journey that started in Japan and would take her six years through Indonesia, East Timor, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Myanmar, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Dubai, Oman, Iran and Europe.

The photographs here were taken with a Panasonic LX100, except for a very few which were taken with a Panasonic GF1 1.7/20mm. On the LX100, over 55% of the photos fell in the 28mm & 70mm focal lengths. The LX100 served me well till I used it one day for taking pictures of a landslide being cleared.

All images ©Farhiz Karanjawala. May not be reproduced without permission.

Thank you, David—looks like this year’s a wipeout as far as travel is concerned. You should write up your experiences in India too. Would love to read them.

Thank you, Farhiz, for a return trip to India at a time when travel has become so difficult. Memories from previous trips to India of places, colours, food, dance, culture and above all the most vibrant and friendly of people come flooding back to me. As a bonus, you take me to new regions and places with your excellent eye for an image. Thank you!

Lovely story Fahriz with great photos illustrating the story line. Illustrating different cultures with photos is a real art and you have succeeded admirably. The warmth and friendship and love of tradition and culture of the people in the photos come shining true. You have shown real empathy in your photos and this is something that comes not from the camera, but from the photographer.

William

Thank you for your kind words, William, I am truly touched. Throughout the north-east I have been welcomed with smiles, been met with kindness and generosity, and made friends of strangers. I’m happy that bits of these have been captured in the photos. Normally, this time of the year, I’d have made my plans for a trip out there again. But here we all are – looking through our photo archives and wondering when we can be out and off again. As the Sufi saints said, “This too shall pass”.

Thank you, Chef — I haven’t yet seen Ugly Delicious, but I hope you can make it one day to see the country, and if you can combine that into a gastronomical tour it would be all the better.

This is a wonderful travelogue and a window on yet another part of India I’m unfamiliar with. I have never been to India, in part because it seems such an overwhelming country, that it’s hard to know where to begin so I remain unfamilar.

David Chang (famed head chef an owner of Momofuku in New York) has been doing a food series called “Ugly Delicious”. He spent 1 episode trying to grapple with Indian food, starting by smashing the stereotype of standard Indian dishes. In the end he is bewildered and enchanted by India and the range of food from Kashmir to Goa that does not fit the clichéd images of India. I love these posts because sooner or later I will be motivated to satisfy my curiosity and book a trip there with the Missus.

absolutely agree with your comments.

As an native of the subcontinent living in Denmark, I try to explain india here in my own way by equating it to European Union. The current entity India is actually many different countries put together (it is a big topic of discussion, on the history of the subcontinent, that is for another day !) and administered as one country ! there are 22 official languages with no national language as we see in European nations… as a native of southern india i speak in english when i have to converse with someone from the north ! it is a novel experiment that we are trying now but how far it would carry on, would be the question, as not many politicians have understood the idea of india… Gandhi, Nehru and some of the latter ones being the exceptions. the sub continent also has a large native tribal population which is not so much known outside (or even to indians !) largely because i think it was the route for migratory routes in the ancient past and there is a huge mix of native/indigenous population…

so if you plan to travel it is almost traversing many countries 🙂 you would experience different language, culture, food when you cross the different provinces/states. only common thing you would find , as Farhiz mentioned, is the love of people especially in the ‘rural’ areas.

All the best !

Thank you, Kevin. That photo of the woman dancing is another of my favourites too.

Thanks Farhiz for this entertaining article. The river photos are special and another that caught my eye was that of the women dancing where you framed the woman nicely with her fellow dancers around her.

Thank you, Wayne. That one taken at Nimati ghat is of course a panorama. But there’s a funny one that my guide took of me that is not included in the article, when I was completely unaware of this stranger behind me who was peering up right over my shoulder as I looked through my camera while taking the pictures, which was with the GF1 in this case. About the LX100’s fate…it got a load of dust into the lens from the earth moving equipment. If you want to read it, I’ve replied to Dave in more detail. Pity I didn’t know about this one flaw it had or I’d have been more careful. It really is a wonderful little camera.

Thank you Farhiz. I particularly like the three wider riverboat shots.

The Leica glass on the LX100 with its 13mp served you well.

But I must echo Dave’s question above. What happened to it at the landslide?

Man would these people fit right at home dancing their way down the street at New a Orleans Mardi Gras or that monster Carnival celebration in South America. I do feel that one could really spend a lifetime wandering India and be surprised every time you turned a corner. Thank you for this and your other articles, I don’t know why but the RAJ has always made me curious.

Thanks John. Every state has its own dance form. In Assam there are three distinct dance types: Ojapali, Bihu and Ankia Nat. Kerala, in the south, has as many as eleven. They would feel right at home in New Orleans as you say.

Thanks Farhiz for that wonderful and colourful article. I particularly like the Majuli series especially the golden light in the last shot with with the reflection of the man on his boat. Following your voyage on google maps to try and locate those villages is a real pleasure in those lockdown days.

Thanks for sharing and keep safe

Jean

Thank you so much, Jean. There was a map marking the places that was included in the initial draft which I removed later thinking nobody would be interested in seeing. I use Google Maps a lot, in fact. So maybe for future articles I may include them again, if it’s okay with Mike.

Perhaps map reference links would be useful in an article such as this.

Thank you for sharing these wonderful memories, its nice to see such colourfully dressed people, and lovely scenes.

The Brahmaputra image with the moon in it, and the wetland image with the colourful reflection of the trees are really decent shots.

I have to say the dancing, perhaps a bit of murder on the dance floor. You clearly impressed the local ladies.

I take it the LX100 expired at the landslide, or got caught up in it?

Keep safe folks.

Dave

Thank you, Dave. The Brahmaputra photos you see here were culled from the dozen or so crossings I’ve made. It was only the one time that the moon was visible during the day. Clearly the women folk at the end had a field day with my dance floor moves (that picture is one I’m quite fond of). About the LX100, I thought I’d leave that bit for another story one day, but since there’s interest in knowing what became of it, I’ll tell it now. It was on the same trip from Majuli to Ziro, in Arunachal, that a landslide was being cleared from the track. At first, I was sitting in the car waiting patiently. We were at a safe enough distance should there have been any further slippage of rock down the hillside. But after a bit, I thought there’d be no harm in getting a few shots of the earth mover in action. So I moved in close to the machine, and then closer, till I was just outside the arc of it’s arm. I took some decent videos, if I say so myself, with my phone all the while the LX was hanging by the neckstrap at my side. So long story short, we continue on our way once landslide is cleared and LX works just fine. Get home, load the images onto the computer and good lord there’s a dust spot on every damn picture after that day. There’s nothing to do but to spot out each one. Then one fine day, I am gifted with, *drum roll*, an X Vario. I sure hope my godson gets the LX sensor cleaned.

i dont which bit to gasp at, the LX100 sensor going spotting, or that a Leica X Vario landing in your lap to help you get over the loss.

Surely the LX100 wont be expensive to resolve, I am sure I read about that during my research that led me to the X typ 113.

It would be nice to see an article on the landslide though, I bet the image – even dust corrected will be interesting to see.