1.Ricarda Schwerin

It was over twenty years ago that I first came across the glass plate negatives taken by Benedict Stolz, a German monk who spent most of his life at the Dormition Abbey on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. In the fall of 2000, while doing a postdoc at the Hebrew University, I organised the academic conference “Weimar in the Desert” about the Jewish writers, philosophers, artists, and musicians, mostly on the far left, who fled fascist Germany in the 1930s and brought their talents and humanism to Jerusalem.

For the conference poster, I wanted an archival image of Palestine from the 1930s. An Israeli friend of mine told me he knew of a German-born, Bauhaus-trained, socialist photographer named Ricarda Schwerin who had recently died and thought she might have left behind vintage photographs. I contacted Schwerin’s son, the historian Tom Segev, and we agreed to meet at his mother’s old apartment on Abraham Lincoln Street.

While Segev couldn’t offer me any negatives from his mother — they had all been destroyed in a flood — he pulled out a case of 350 glass plates and offered to sell them to me. He had no idea who took the photos. All he could say was that as a boy in 1967, he recalled a Palestinian selling the collection to his mother.

Schwerin was impressed enough by the quality of the unknown photographer’s work that she gave the collection to the Israel Museum, expecting them to organise an exhibition around the collection. She believed that the images, taken between 1920 and 1943, told a story the Israeli public, and the world, should get to know.

And it was a story of a conflict she knew all too well. Schwerin had fled Nazi Germany with her husband, Heinz. When they arrived in Palestine in 1935, the Old City of Jerusalem and the surrounded countryside seemed unspoiled, as if untouched by the modern world. But the Jewish-Arab conflict had already begun, and Heinz was killed during the civil war that broke out in 1947.

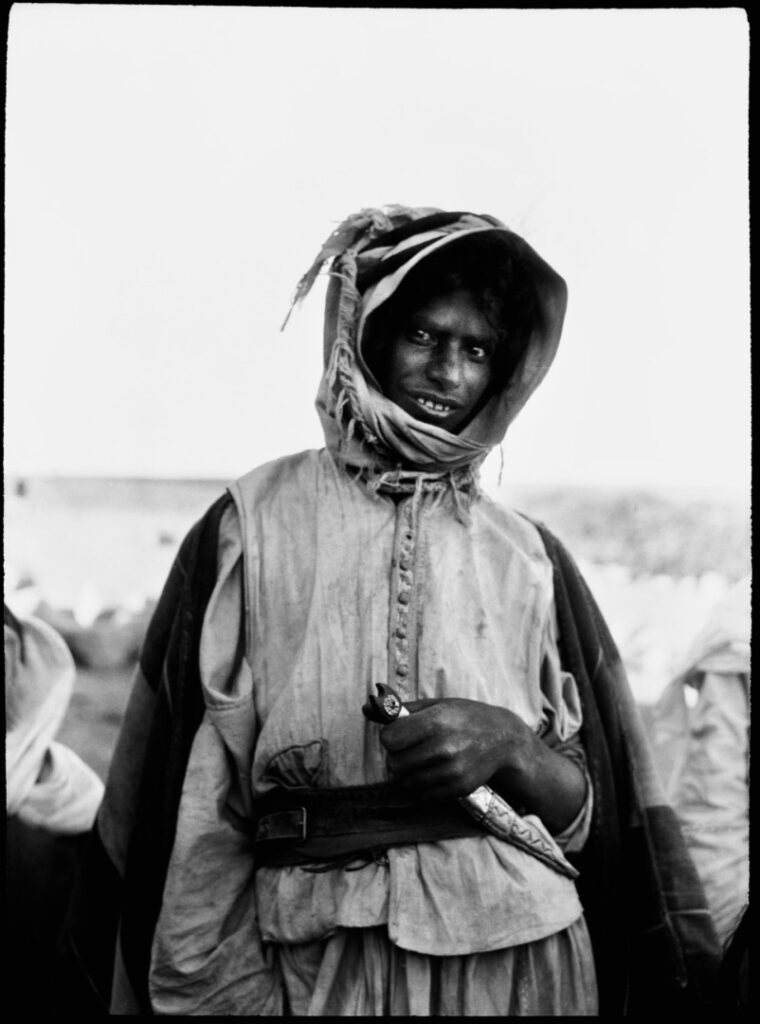

In the mystery photographer’s landscape images and portraits from the 1920s, she recognised this lost Eden. At the same time, photos with titles such as “The Beggar,” “The Child”, and “Jihad” taken during an outbreak of Arab-Jewish violence in 1929 captured the poverty and brewing conflict destined to tear the country apart.

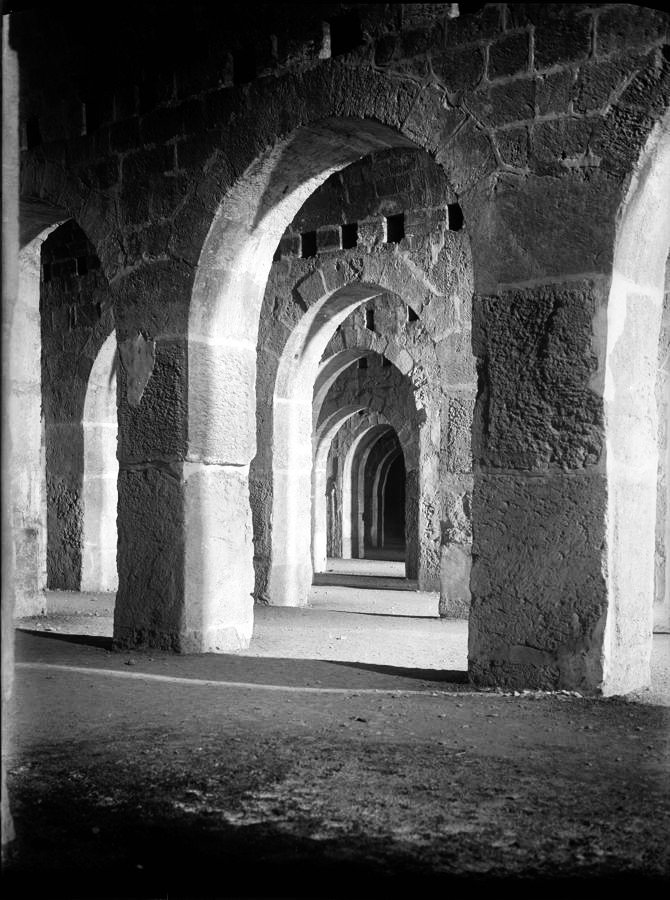

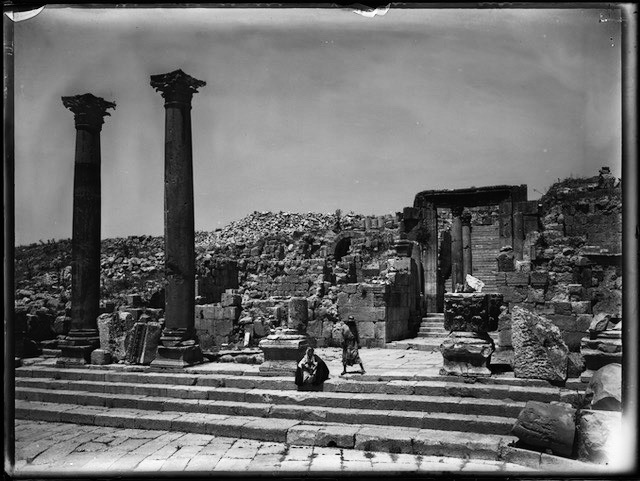

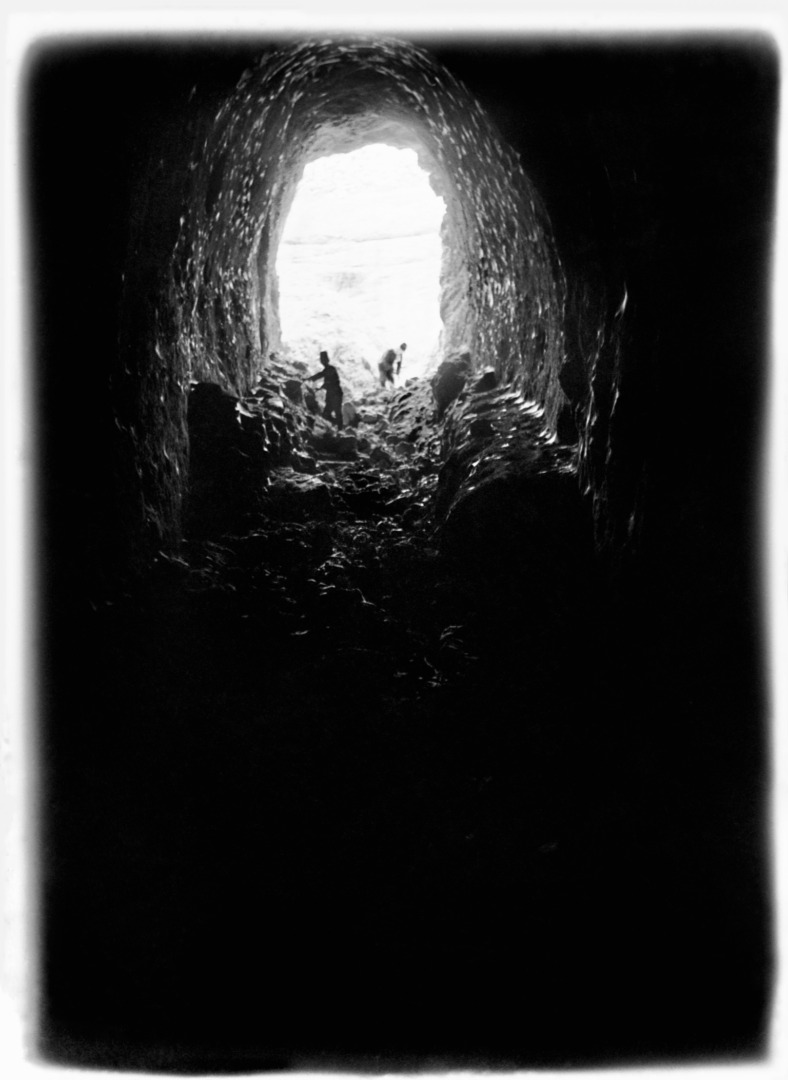

A year later, in 1930, photos taken at a Jewish kibbutz showed shifting allegiances. Schwerin was an architectural photographer and was especially intrigued by an analogous change in the photographer’s interest. In the 1920s, he photographed Greek and Roman temples, while in the 1930s his photos were of churches, shrines, and icons. The titles he gave to these pictures, like “The Inferno,” taken at Solomon’s Stables under the Al Aqsa Mosque, hinted at a more internal conflict at work inside the man.

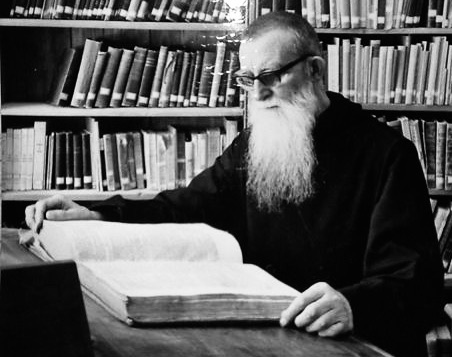

2.Benedict Stolz

The Israel Museum kept the plates in a storage room for years, until Schwerin eventually reclaimed them, vowing to discover who was behind these masterpieces. But she knew all the photographers in the city, and none could identify him. The man couldn’t have returned to Germany after 1940 because he would have taken his treasure trove with him. Had he died or been killed? Had the collection been stolen?

But Schwerin, a single mother raising two children, couldn’t put her own work to one side to sleuth for the photographer’s identity. She was also a very good artist in much demand — in 1974 Hannah Arendt urged her in a letter, “You must not give up photographing under any circumstance” — and the collection stayed under her bed when she died in July 1999.

When I bought the collection from Segev, I inherited his mother’s obsession, too. I must have talked to every photography expert in the country, but no one could help identify the photographer. Three years after I bought the collection, on what I vowed was my absolute last attempt, I visited the Ecole Biblique, a Dominican monastery in East Jerusalem because its scriptorium contained 250,000 volumes on the Holy Land.

Down in the stacks, I began randomly flipping through volumes in German, looking for photographs. Finally, in the 1931 edition of the archaeological journal Palästinische Hefte (Palestine Magazine), I found a reprint of a photo from the collection, “Memento Mori,” which shows a British soldier standing amid the rubble in the city of Nablus following the cataclysmic 1927 earthquake in northern and central Palestine.

The photo was attached to an article describing the earthquake as coming from the same “jagged tear in the earth’s crust” — the Jordan Rift Valley — that “in the Iron Age brought on the doom of Sodom and Gomorra.”

At the time the photographer was sitting in the scriptorium of the Dormition Abbey, built out of the ruins of a Byzantine shrine to the Virgin. Suddenly the building began groaning, all the way to its foundations. Heavy pieces of ceiling plaster rained down around him, leaving him in a cloud of dust, and giving him the sensation as if a tornado has suddenly arisen and was about to rip away the roof, whirling it into the heavens.

The Kingdom of God is Within You

Cracks appeared in the thousand-year-old walls, doors came unhinged, and bookshelves toppled over. The other monks clamoured out the door and raced pell-mell upstairs.

More amazed than frightened, the author found himself alone in the rubble and dust.” The quake, he concluded, is a poignant allegory for my life.” He was reminded of the true meaning of “memento mori.” Hence the title of the photo.

At the bottom of the page, an asterisk identified the author and photographer as Benedict Stolz, a monk at the Dormition Abbey on Mount Zion.

Adrenaline pumping at this stroke of luck, off I ran through Damascus Gate, into the warrens of the Old City, and I exited the Lion’s Gate before arriving at Mount Zion. Nikodemus, a young German monk I met that morning, took me to the attic of the monastery where Stolz’s effects were kept. In the following three months, I was finally able to do what Schwerin couldn’t: decipher the story Stolz told through his collection.

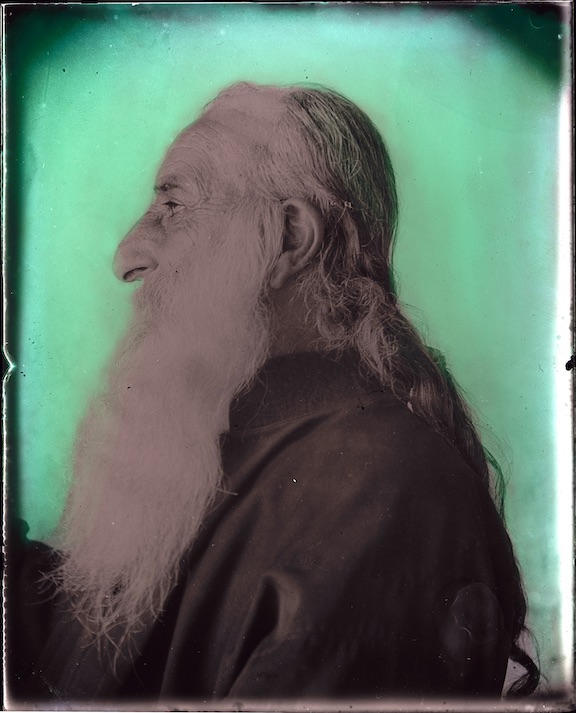

In 1975, after the mayor of Jerusalem awarded Stolz the city’s top honour, a prize shared by Chagall and Noble laureate in Literature SJ Agnon, an historian at the Hebrew University interviewed Stolz about his life. “It was on January 6, 1895, exactly eighty years ago,” he told the interviewer, “that God allowed me to see the light of day. I was born in Erkrath near Düsseldorf.” His name at the time was Arno Henricus Constantinus Stolz. He adopted the name Benedict after taking his vows.

A photo I found in the attic shows his father Peter with a neckless throat and a hard-driving intelligence projected through his eyes. Not the kind of fellow you want to cross. His mother Agnes, who was from Alsace and insisted on speaking French at home, was determined to train Arno’s imagination just as her husband was working on his son’s equally promising analytic mind. She liked taking him on walks outside of town to the Neanderthal, just over the hill from the ironworks churning out steel for Germany’s growing military. There it was, down a hillside path cutting through a stand of trees and alongside a fast-moving stream, that Homo sapiens neanderthalensis was first discovered in 1856.

Agnes also engineered her son’s life in the church, but less out of piety than the love of art and music. Someone in the local parish, knowing that the young Arno had a talent for art, told Agnes about the art school at Beuron. Led by Paul Gauguin’s pupil Jan Willibrord Verkade, the artist-monks there had participated in the Vienna Secession art exhibition organised by Gustav Klimt.

Agnes and Arno were soon on a train through the Danube Valley to enrol him in the art school. Arno soon went by Benedict, and at Beuron he was drawn most to the Palimpsest Institute attached to the scriptorium where the monks used infrared photography to peer behind the surface of medieval illuminated manuscripts in search for ancient classical texts on the underlying vellum. One intrepid researcher found a copy of Cicero’s On the Republic buried under Augustine’s meditation on the psalms.

3.Palimpsests

Through interviews with the historian of religion at the Hebrew University, Professor Raphael Werblowsky, and especially the 99-year-old Italian priest Monsignor Albino Gorla, I learned just how much the Palimpsest Institute taught Stolz to see — or introduce – multiple meanings into images.

It was just as Schwerin suspected. The 350 glass plates tell the story of a man thrust into one of the most dramatic moments in history. In the space of a year, from August 1929 to July 1930, he went from siding with Arab rebels against the Zionists to joining a circle of anti-Nazis in Germany determined to prevent Hitler’s rise to power. An encounter with the mystic Therese Neumann in the Bavarian village of Konnersreuth in 1930 turned him into both a fervent admirer of the Kibbutz movement in Palestine and a believer in the power of women to confront evil.

The darkest images in the collection reflect his horror that his closest friend from the Beuron art school, Hermann Keller, seemed to have sided with the Nazis and had a hand in preventing the Jewish philosopher Edith Stein from immigrating to Palestine.

4.Lost and found

In 1940, the British arrested Stolz on charges of lending support to the Zionist underground army, the Haganah. It was only three years later, after his release from a prison camp near Tel Aviv, that he put the plates into their final order. The last images in the collection, such as “Out of the Depths I Cry to Thee,” from Psalms 130, reflect his anguish at rumours that reached him in 1943 that Hermann Keller had joined the SS and gone to work for Reinhold Heydrich, a principal architect of the Endlösung — the Final Solution. Keller was also said to be responsible for sending Edith Stein to the gas chamber in Auschwitz.

Stolz stored the collection along with his camera equipment — an old wooden-and-brass warhorse of a camera and a Leica I Schraubgewinde — in his cell, which was where they were when the Arab Israeli war broke out in 1948.

In Jerusalem, Arab soldiers concentrated their forces behind the walls of the Lion’s Gate in the Old City. In an effort to drive them out, the Haganah mounted an assault from Mount Zion. The Arab forces fired round after round of mortar onto Zion Gate to prevent the Israelis from gaining a foothold.

During the battle, the monks were down in the crypt, far into the limestone belly of Mount Zion. The main church building took a direct mortar hit, and the other monks wanted to flee before the Israelis arrived at the monastery. Stolz had seniority at the monastery, and he used his authority to prevent anyone from leaving. He and his fellow German monks would have to trust that the Jews would show them mercy despite what Germans had recently done to them in Europe.

Using the butts of machine guns to break through the oak door leading to the crypt, a group of Israeli soldiers marched down the spiral stone stairs. A soldier raised his gun to fire when an officer came down the stone steps and ordered him to put his rifle down. “Dr Stolz,” the officer said in Hebrew, “you’ll have to evacuate the monastery at once.’” With bullets whizzing around them, the monks filed out of the monastery. The monks found shelter in the St. Charles Borromeo monastery in the German Colony, a building they shared with Holocaust survivors.

When the newly established Israeli government allowed the monks to return to Mount Zion two years later, Stolz found a half-destroyed monastery. His collection of plates had been looted.

Stolz died in 1983, and he never knew that for years the collection he believed was lost forever was gathering dust a mile away under Ricarda Schwerin’s bed on Abraham Lincoln Street.

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

Another wonderful photographic mystery. I love these historic images, they are an amazing testimony to what we can do with a camera, and the records that can be kept.

I do wonder if someone finds my hard drive in fifty years time, they will look at my images and wonder what i was thinking.

Thank you for sharing this incredible story and stunning images Anthony! It is wonderful that you were able to uncover the mystery of the photographer and his fascinating life. Also incredible that the glass plates survived and will be preserved for the future!

Dear Anthony,

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your story. You can tell it was written by a pro because of beautiful language, rich details, sharp observation and carefully researched facts. I was additionally hooked because of Stolz’ connections to Beuron. This is close to where I live; I know the Beuroner Schule from the art historian’s point of view, and I read a little the abbey’s role during the Nazi regime. But your story reminded me strongly of the fact that everything is connected and interwoven and that no act, no thought, no omission is isolated. Here, I can only support what William Fagan with this great knowledge wrote.

Thank you very much for sharing this fascinating story. JP

A beautiful story and what fantastic pictures!

Thank you very much – fascinating story and amazing pictures!

A great story, Anthony, and very well told. Our preserved images are all part of our history and teach us about who we were and who we are. Given what was happening in that part of the world, we are very lucky to have the glass plates of Benedict Stolz. Given how fragile they are it is good that they have survived and are now in good hands. Benedict Stolz seems to have travelled around a large territory. I visited Jerash in Jordan about 14 years ago, but I only have a couple of photos from there. The rest were on a laptop which was stolen about 11 years ago. So were some of my photos of Damascus, but I managed to save enough of them to able to produce an article for Macfilos which has also appeared in a magazine in the US and on 3 different live presentations. All of this is to show why we should celebrate the finding and preservation of these glass plates. I know some people here in Dublin who are still doing glass plate photography and also people who are involved in preserving old glass plates. I like the use of the Memento Mori concept here. There is a quote from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar which goes ” The evil which men do lives after them, the good is oft interred with their bones” . In this case the glass plates (which are good rather than evil ) of Benedict Stolz have lived after him and thankfully they are not interred with his bones. We photographers should never forget that message even in respect of our most humble photographs .

William

A truly enthralling story. Amazing images. A wonderful start to the weekend. Thank you

Jean

Fantastic monochrome! And a fascinating story. Thank you.

Those are gorgeous, what a treat! Please one of the Mac readers please pass to Nils Thune, Scandinavian Leica photog who has series on Monastic residences and life. Saw him on Leica camera blog. These are terrific.

Fascinating account. All the hard work and dedication paid off in the end.