Until around twelve years ago I knew nothing of George Hackney But since then he has been responsible for my becoming a twice published author, research consultant for a documentary film company, and more recently, consultant for a theatrical stage play currently in the process of production. So who was this man?

It was William Fagan in Dublin who suggested I put together this article on this relatively unknown Great War photographer from Northern Ireland.

The connection

George Hackney was born in Belfast in 1888. As far as I could establish, he was active in the world of photography from around 1910, initially taking photographs during rambling holidays with an organisation called the Co-Operative Holiday Association (CHA), set up to facilitate affordable group holidays across Britain and Ireland for working-class men and women.

My connection to Hackney, however, began on September 14, 1914. I can be that specific because on that date, following the outbreak of the Great War, George enlisted in the 14th Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles. He was enrolled into ‘B’ Company, number 7 platoon and thus came under the charge of one Sergeant Jimmy Scott, who just happens to be my great grandfather.

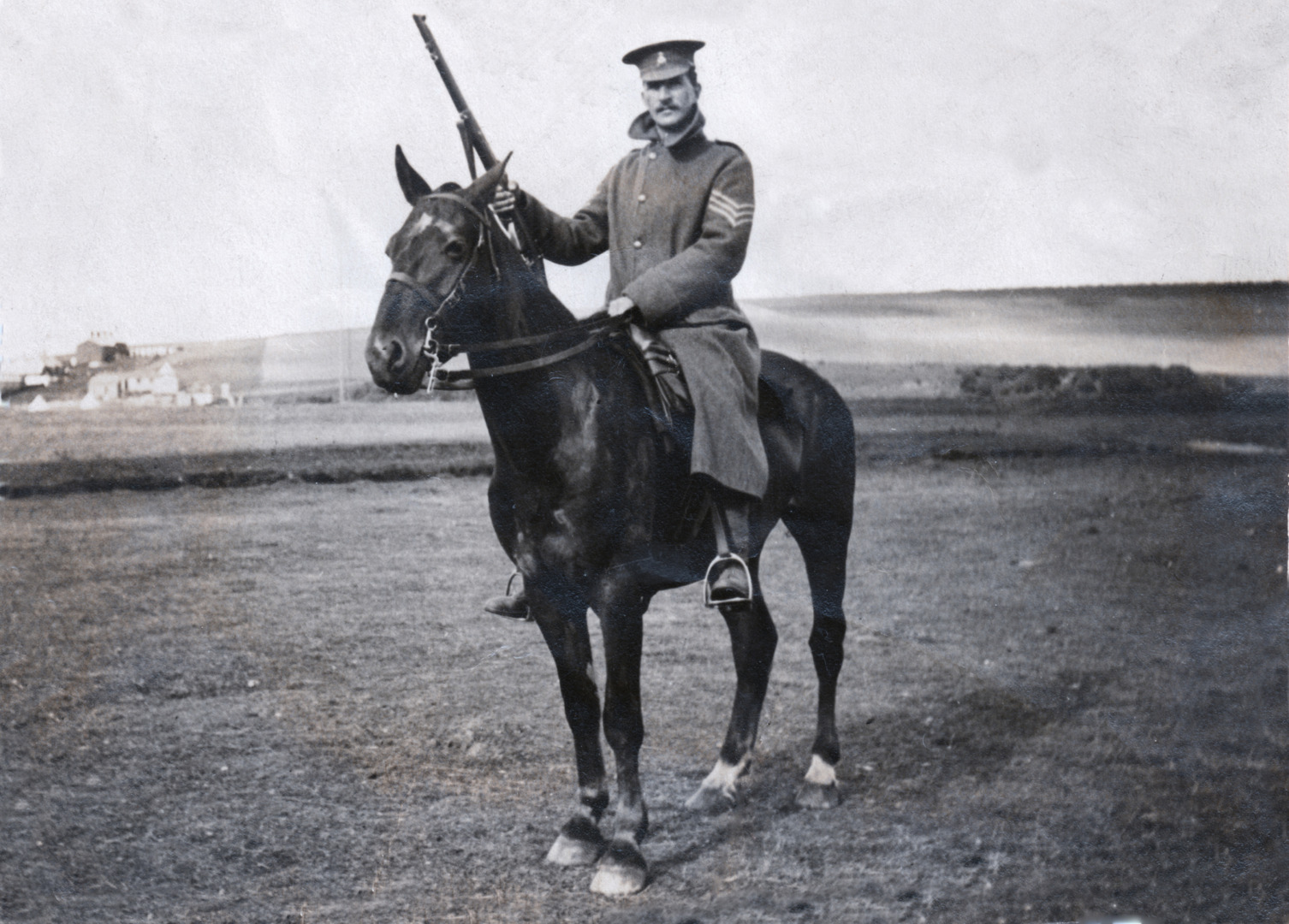

Around 2010, before I knew any of this, a rather rough photocopy of a photograph appeared in my family. I could see that it was of a soldier sitting on horseback and carrying a rifle.

I was informed that this image was of Sergeant Jimmy Scott. I attempted to find the original, enquiring with relatives and was told that it may have been taken to America with a branch of the family. I began researching Jimmy Scott, making contacts with local military historians.

The collection

One of these historians had by chance been given access to a Great War photographic collection at the Ulster Museum in Belfast. He contacted me and enquired about my great-grandfather’s service number. I told him the number and he confirmed to me that he had seen a photograph of Jimmy Scott’s grave, taken in January 1917 with the soil on the grave freshly turned, his name and service number were inscribed on an original wooden cross.

To say I was shocked was an understatement. I eventually gained access to the archive with the assistance of the curator, William Blair, and from that moment worked to understand as much as I could about the collected images. The great point of interest is that the photographer was identified as being George Naptali Hackney, from Belfast.

It wasn’t long before I found an original print copy of the photocopied image that had been passed around my family. The image created an immediate strong impact. For the first time, I could see what my great grandfather looked like. I could almost look him in the eye as he stared out from the paper.

More than that, the photograph was taken and composed in such a way that it projected the personality of the man. Here was sergeant Jimmy Scott, mounted on a beautiful horse, with his rifle in hand and greatcoat collar turned up. The image was perfectly composed and technically perfect. If there was ever an image to portray an Irish warrior, this was it.

The quest

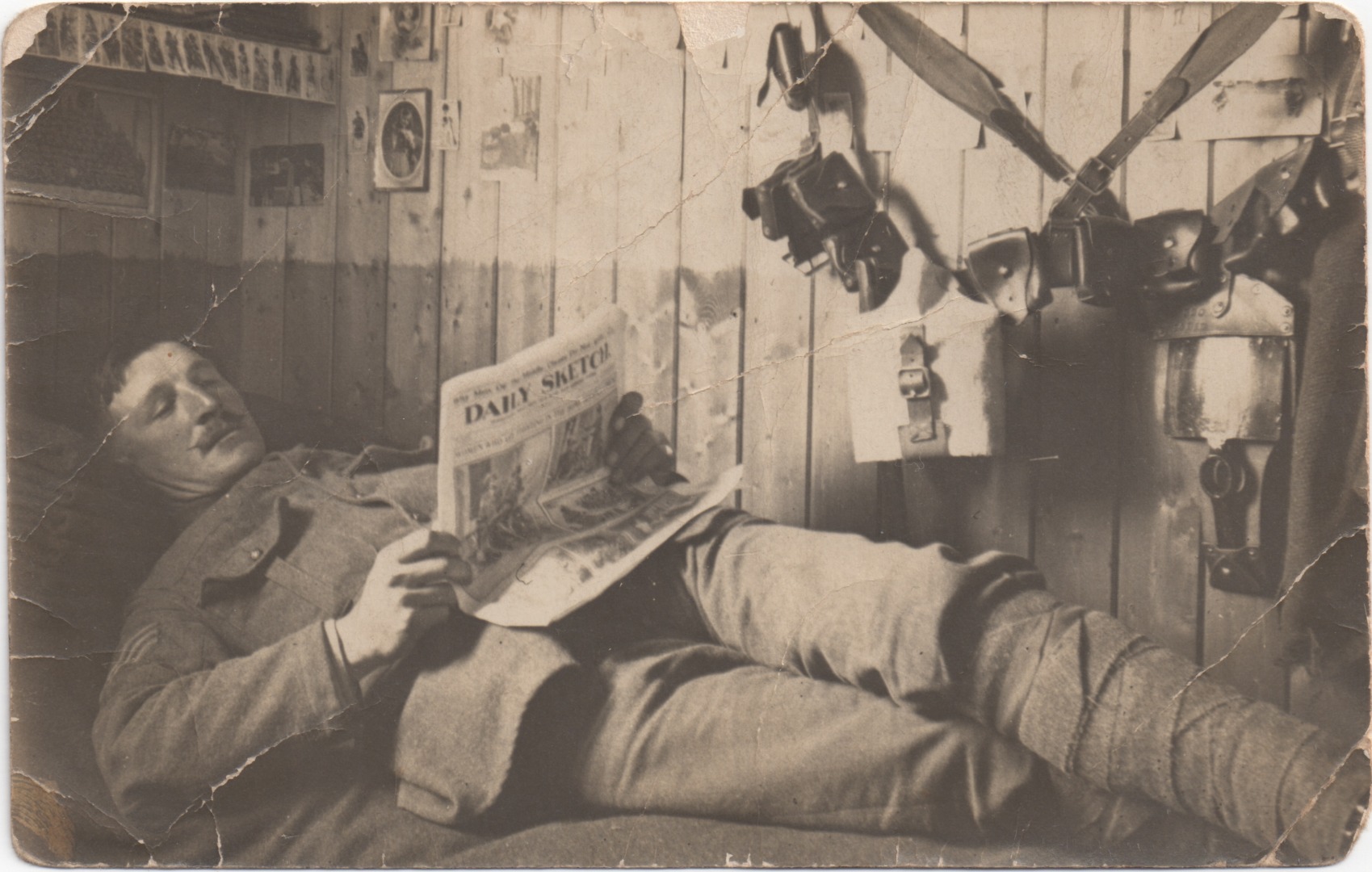

From that moment, back in 2011, I have spent years attempting to place the collection of some 120 images in context with regard to time and place. This work led me to France and Belgium, back to the old battlefields of the Great War. Although George Hackney was an early hobby photographer, he was by then first and foremost a soldier. Photography was forbidden in the British Army, punishable by imprisonment under martial law.

If a man were to be allowed to take photographs and later be taken prisoner, or his camera is found on his body by the enemy, then the information obtained from the developed images could be of intelligence use and a danger to his colleagues. George appeared to have made a local ‘arrangement’ with an officer in his battalion, a captain called Thomas Mayes.

Along with the photographs, the archive contained diaries written by George. On examination of the written work, it appeared that Captain Mayes facilitated the posting home of his photographic plates, outside of the official censor. When one examines some of George’s photographs, it is obvious that they would have been of intelligence use, for instance showing the layout of German trenches. It was also discovered that George was a scout/sniper in the battalion. These men were trained to sketch enemy positions with paper and pencil. It seems that George found a better, more accurate way of doing his job by using a camera.

The documentary

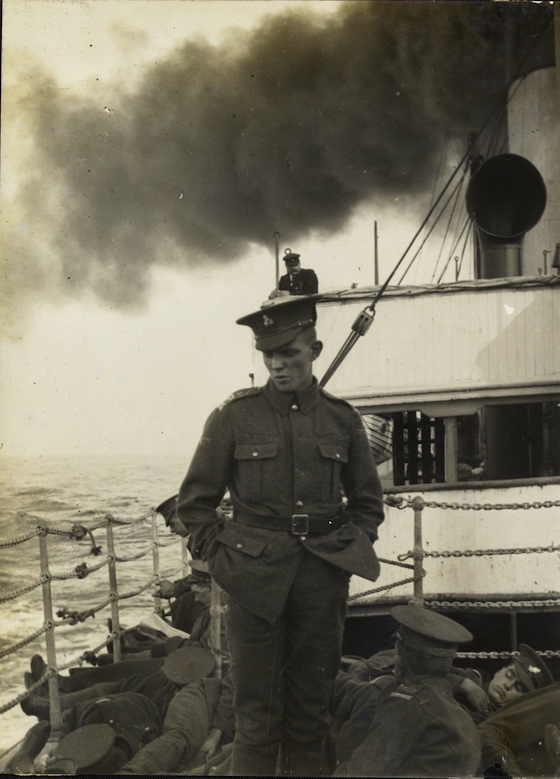

In 2014 I was contacted by Brian Henry Martin, a film producer with DoubleBand Films in Belfast. He had heard about the archive and the research which I had carried out. I went to France and Belgium armed with two Leica M8 digital cameras and set about reconstructing the photographs which George had originally taken.

The exercise was a great success. George had essentially photographed the journey that Number 7 platoon had taken through training in Ireland and England right up to the great battle on July 1, 1916, at Thiepval and then on to Belgium.

I was acutely aware that George’s journey was identical to that of my great grandfather’s. I could follow almost step for step in his footsteps. DoubleBand Films made a documentary of this journey which aired on the BBC in November 2014, titled ‘The Man Who Shot The Great War’. I was encouraged by the producer, Brian Henry Martin, to rewrite my research work into a book. The book, also called ‘The Man Who Shot The Great War’, was published in 2016.

Of all of the Hackney photographs, those which impressed me most were a trio taken by George on the morning of July 1, between eight and eight-thirty. They record the first hour of the Battle of The Somme at Thiepval in France. They are stunning in that they were taken during a battle that has been described by historians as the worst day in the history of the British Army.

Two images depict lines of German troops surrendering to the advancing Royal Irish Riflemen. A third shows a view looking across the Ancre Valley, to the left and rear of George’s line of attack. On taking this image George would have realised from the position of the exploding shells on the British lines across the valley that the supporting battalions on his flank had not advanced further than their own wire.

At that moment the battle turned with the 36th (Ulster) Division, of which George’s battalion was a part, left unsupported and outflanked by the enemy. George and Jimmy Scott spent the next two days fighting for their lives in a rearguard action to make it back to their own lines. Almost half of his battalion of nearly a thousand men were lost, missing, wounded, or killed in action.

In my opinion, these images are comparable to those produced by the great Robert Capa, taken on June 6, 1944, at Omaha Beach in Normandy. The difference is, apart from the quality, that George Hackney was a fighting soldier and not an embedded photographer.

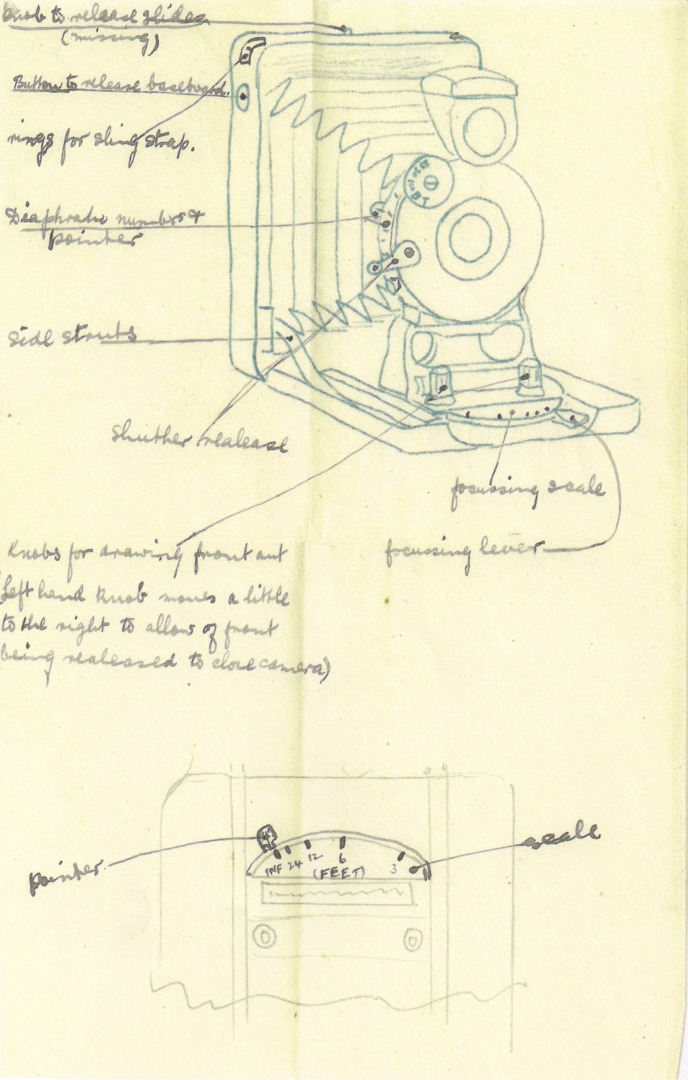

George used a Watch Pocket Kilmax camera which could be quickly expanded and collapsed during use. It had the advantage of being easily carried in a tunic pocket or in a kitbag. Before deployment in France, George listed his equipment in his diary as follows: Watchpocket Klimax Camera, 12 sheaths, 8 doz plates, changing bag, photo record book, flash lamp, watch, 2 body belts, ink, and pens.

George Hackney’s work is outlined in the publication ‘The Man Who Shot The Great War’ by Mark Scott ISBN 978-1-78073-095-0 published by Colourpoint Books.

Photographs are courtesy of the Royal Ulster Rifles Museum, Belfast, The National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’is of the United Kingdom, and the private collection of the author, Mark Scott.

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

Fabulous article Mark! Many thanks for sharing this incredible story, the photographs are just stunning. I love how your own genealogical research led to the wonderful story of George Hackney.

Thank you Mark For this amazing article

Jean

Thank you Mark,

I found it interesting that he used plates which I assume made the job of sending them home that much more difficult. A valuable record of the time.

Wonderful storytelling – thank you. Even after getting on for 120 years after the start of WWI there are still stories to be unearthed about the horrors, the muddled strategic thinking and the simple comradeship that persist to this day.

Thank you, what a gift.

Beautiful, great photos, great storyline, great relatives! Posterity has been well served by yours. Thank you

Great to see here, Mark. Also it was good to have you at the Gallery of Photography, Ireland last week to see our Martin Parr exhibition.

There are a number of points about George Hackney’s story which are remarkable. The first of these relates to the prohibition on cameras at the front in WWI introduced by Kitchener after photographs had appeared following the ‘football fraternisation’ between the warring sides at Christmas 1914. For some reason George Hackney and another Irish photographer, Father Francis Browne SJ, were both allowed to carry cameras at the front. I suspect, as you do, that Hackney was a spotter or a sniper, but Fr Browne did not have such an excuse, except, perhaps, because he was the Jesuit who took the last photos of the Titanic.

The other difference was that George Hackney was a Presbyterian, but late in life he met a fellow veteran (from the US if I remember correctly) who had become a Baha’i. After some years of thinking about the matter, George Hackney left the Presbyterian Church to be come a Baha’i. However, the story does not end there. As I recall, it would have been very difficult and vary expensive for you to have completed your book and film without the aid of the Baha’is who only sought a copy of your book as a payment in return. Out of such kindnesses are histories made.

I love the handwritten instructions for the Houghton Butcher camera. I must share these with the guys at the Photographic Collectors Club of Great Britain who are very expert about cameras of that era. Maybe we might even some day get around to doing that project, which we discussed, in which I would shoot the locations of the WW I battles with a WWI camera and you might shoot the same scenes with one of your Leicas. The photographs in your book, mentioned above, are stunning. I am thinking, particularly, of one set of photographs joined up to show a walkway in a battlefield zone with pools of water and a shell going off in one of the pools right beside a soldier who is calmly washing his uniform. George Hackney saw and captured it all over 100 years ago. Then there are the British soldiers in goatskin jackets …… and a lot more.

You have done a great service to the ordinary military men of that era, not only in recording what they did, but also in not letting their memory fade from your and our view.

William