Sirui, pronounced ‘soo-ray’, joined the L-Mount Alliance in March 2025, further diversifying the system beyond its heavyweight founders, Leica, Panasonic, and Sigma. As well as offering lower-cost options for popular spherical lenses, the company has brought a new and exotic dish to the L-Mount feast: anamorphic lenses.

Sirui is by no means the first third-party lens manufacturer to have joined the alliance, but it might prove one of the more consequential.

The company, formed in 2001 and based in Zhongshan City, Guangdong Province, China, manufactures a range of camera accessories. According to the company’s website, it had been producing tripods since 2006, but only began investing in lens-manufacturing capabilities in 2015.

Sirui came to the attention of the content-creation world in 2019, when it released a series of affordable anamorphic lenses for cinematography. Up to that point, anamorphic cine-lenses were typically expensive, accessible only to large commercial operations. Several generations later, Sirui has an extensive range of anamorphic lenses for both video and stills photography — hence the interest to Macfilos.

Before going further, I think a short diversion is in order to explain what the anamorphic format and anamorphic lenses are all about. I, for one, had heard the term bandied about for a while, without really understanding what it meant. So, for those not familiar with anamorphic lenses, here’s a quick overview.

Shape shifter

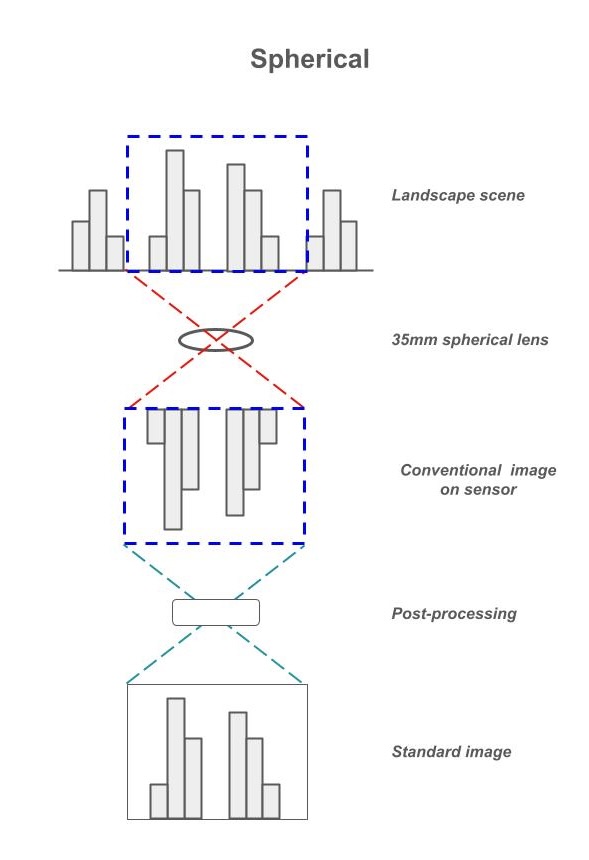

The spherical lenses with which we are familiar, almost certainly sitting on our cameras right now, produce a circular, unaltered image.

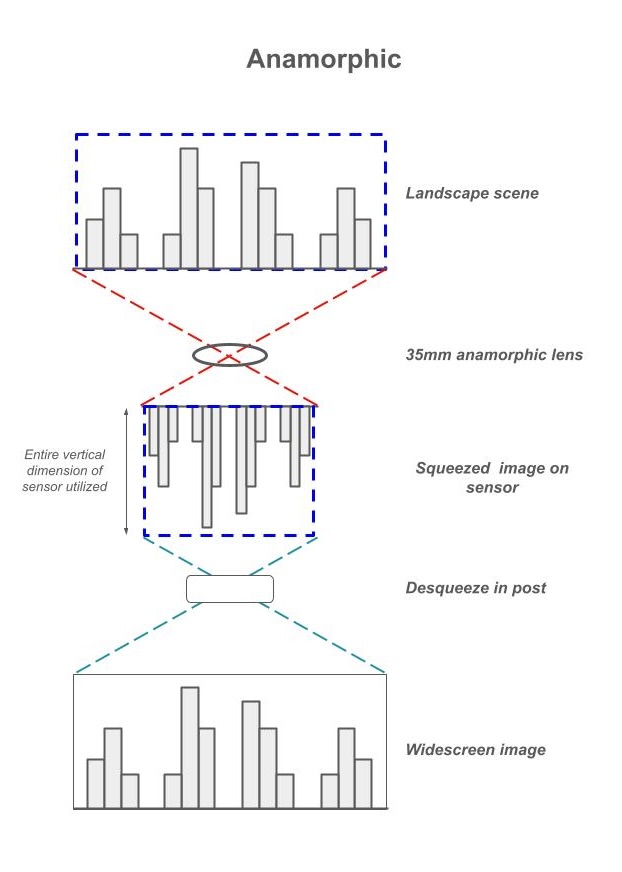

In contrast, anamorphic lenses produce horizontally compressed, oval images. These must be stretched during post-processing, to return them to life-like proportions.

Why, you might ask, would anyone want to go through such a rigmarole?

To understand this, and the motivation for introducing such a tortuous optical manoeuvre, let’s take a brief excursion into the history of cinema.

CinemaScope

The popularity of television in the 1950s meant that rather than going to the cinema, people could just watch shows at home. So, in order to compete, film-makers sought ways of making the cinema experience more exciting.

One obvious way to fight back was through wide-screen movies – much more immersive and spectacular than a small square box in the corner of the room. You might recall statements such as Shot in CinemaScope in the opening credits of your favourite Western back then.

Capturing these wide-screen effects, using standard, readily available 35mm film stock, required an innovation: anamorphic lenses. The name has a Greek derivation, (αναμορφικός, οr reshaping).

These lenses ‘squeeze’ the image horizontally, so that the optical information contained in a wide-aspect-ratio scene could fit onto a film with a narrower aspect ratio.

At the cinema, the film would be run through a special projector, which ‘desqueezed’ the image. Bingo! The audience was treated to a spectacular widescreen picture.

That cinematic look

By using the full height of the film frame or, these days, a digital sensor, this approach retains more resolution than cropped, non-anamorphic widescreen formats.

The CinemaScope format, first used by 20th Century Fox, achieved a desqueezed aspect ratio of 2.55:1. Today, common anamorphic aspect ratios include 2.39:1, and 2.55:1.

I took the photographs in this article using a Sirui 35mm T1.8 1.33-squeeze Super 35 anamorphic lens I bought used, mounted on a Leica TL2. The 1.33 squeeze means that the 3×2 image captured on the sensor is stretched in the horizontal dimension by 1.33x when ‘desqueezed’. So, it becomes a 3.99:2 aspect ratio, which is approximately 2:1.

Anamorphic lenses have more complex optics than standard spherical lenses, requiring more light to achieve a correct exposure. In fact, Bausch & Lomb, an optics company, received an Academy Award in 1954 for the development of their CinemaScope lens.

Anamorphic lenses can also introduce distinctive distortions and lens flares — more on this below. However, these artefacts are sometimes deliberately embraced for their aesthetic appeal.

In these days of social media, video creation is well within the purview of the unwashed masses. Accordingly, the ‘cinematic’ look produced using anamorphic lenses has become highly sought after.

Sirui is meeting that need with affordable, high-quality anamorphic lenses, compatible with a range of camera mounts, including now the L-Mount.

Properties of anamorphic lenses

Although anamorphic lenses are most commonly used in videography, they also offer stills photographers the prospect of that cinematic aspect ratio. Of course, in principle, you could crop an image to a 2.4:1 aspect ratio instead of using an exotic anamorphic lens. But, the result is not quite the same. The advantages of the anamorphic approach go as follows.

First, an anamorphic lens captures a wider horizontal view than a spherical lens of the same focal length. For example, a 35mm anamorphic full-frame lens with a 1.6 ‘squeeze’ produces an image with a horizontal dimension comparable to a 22mm lens. In doing so, the entire vertical dimension of the sensor is retained, so no pixels are discarded.

When cropping to achieve the same aspect ratio, you would need to use a wider-angle lens. You would therefore both forego the optical properties of a 35mm focal length, and sacrifice sensor real estate above and below the image.

Second, anamorphic lenses produce unusual, ellipsoid bokeh, rather than the circular bokeh to which we are accustomed. Together with their unusual flare properties, these oval specular highlights contribute to the characteristic ‘cinematic’ look of anamorphic lenses.

A flare with flair

Finally, the flare produced by these lenses projects horizontally from the light source at which the camera is pointed. It is also typically blue, conveying an otherworldly, slightly sci-fi feel to the image.

This characteristic, striking, flare is produced by a cylindrical element at the front of the anamorphic lens. Light striking this element at certain angles results in the horizontal flare, the colour of which is governed by the coating used. Typical coatings scatter blue light preferentially.

The film director, J.J Abrams, is known (perhaps even notorious) for his extensive use of this anamorphic flare in his films. You can see it yourself in clips of Star Trek movies he has directed. Watch out for the flare as the camera pans around the bridge of the USS Enterprise, under heavy attack by those pesky Romulans.

It’s an acquired taste, but I think it’s fabulous.

It’s getting better all the time…

Initially, Sirui released manual-focus anamorphic lenses for cropped-sensor cameras. As mentioned above, the one I own is designed for the Super 35 format, similar in size to an APS-C sensor.

Subsequently, the company released its Venus, full-frame anamorphic series, followed by a much more compact Saturn series. The latter employs carbon fibre in the lens barrel to minimize weight.

Both series have a T2.9 aperture. Because of their more complex optical design, and the need for consistency when switching cine lenses during a shoot, anamorphic lenses use T-stops rather than f-stops.

Whereas an f-stop is a calculated property, indicating the amount of light a lens should transmit, a T-stop is a measurement of the amount of light a lens actually transmits. The directionality of T-stops and f-stops is the same, however: the smaller the number, the faster the lens.

Most recently, Sirui has introduced the Astra series, the first full-frame anamorphic lenses with autofocus. Here is a recent online review.

It’s an impressive accomplishment, indicative of Sirui’s commitment to continued innovation in lens design.

A galaxy of lenses

In this article, I have emphasised the company’s anamorphic lenses, such as the Astra, Venus, and Saturn series, primarily because of my fascination with this niche corner of the lens world.

But Sirui also produces low-cost spherical lenses for L-Mount cameras, such as the Aurora 85mm f/1.4. Online reviews suggest the lens is optically excellent, very compact, and outstanding value for money.

Since I am a newbie to the world of anamorphic photography, I bought a used, older-generation Sirui anamorphic lens so I could gingerly dip my toe in the water. I have included a few example shots throughout the article to illustrate that cinematic look.

This final image illustrates how the wider field-of-view of an anamorphic lens can add additional context in a self-portrait shot. I threw in a flashlight for good measure, just to see that flare again.

It’s a camera lens, Jim, but not as we know it…

Having taken this initial step, I plan to keep an eye on this quirky segment of the lens world, which I find fascinating. Depending upon how I get on with my new anamorphic acquisition, I might even spring for a state-of-the art model. I’ll keep you posted. I also plan to cover the post-processing steps involved in de-squeezing images in a future article. It is very straightforward.

Meanwhile, I shall continue to put my 35mm T1.8 Super 35 1.33 squeeze anamorphic lens through its paces on my Leica TL2. It won’t be on the bridge of a starship, but it might be on a bridge across San Diego Bay.

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

Keith

Surely your comment: “In these days of social media, video creation is well within the purview of the unwashed masses”, should be a contender for the Macfilos 2025, “best turn of phrase” award?

I look forward to the next instalment of this engaging topic featuring shots from San Diego Bay.

Chris

Thanks, Chris! It’s good to know I’d have your vote if Editor Mike ever decides to add this one to the Macfilos End-of-Year Review award line-up. All the best, Keith

Hi Keith,

Really interesting article! In the past I’ve sort of skipped over articles I’ve seen about anamorphic lenses because I’m not a video or cinema shooter. I hadn’t thought of using anamorphic lenses for stills but it’s enticing. I am looking forward to your follow-up article.

Cheers,

Joel

Thanks, Joel. It’s been fun dipping into this corner of the photography/cinematography world. The Lumix S5 provides good support for anamorphic video recording, and I presume the S5II does too, enabling you to see a live de-squeezed image on the rear tilting screen. Unfortunately, the S5 does not provide similar support for anamorphic stills photography. Perhaps they will introduce it in future firmware updates if interest in anamorphic photography continues to grow. All the best, Keith

Fascinating, thanks for the explanation and the history. Like an f/0.95 lens, I think anamorphic lenses are intriguing, though useful in a limited number of situations (like night time with lights giving lens flare as you illustrated).

Do you have to “unsqueeze” the resulting images in Photoshop or something similar? How do you do that?

Kudos for using a TL2 – nice.

Hi Andrew, Many thanks!

I have a follow-up article coming out in a few weeks which delves deeper into the optical properties of anamorphic lenses (in comparison to spherical lenses of the same focal length) and includes more example shots and a step-by-step description of the de-squeezing process. It is indeed done using photoshop, selecting ‘Image size’ under the ‘Image’ menu, and simply multiplying the horizontal dimension shown by the lens’s squeeze factor.

I agree that for still photography, use of anamorphic lenses is very much a niche. I think they work well when including two subjects in the wide frame, perhaps one in the foreground and one in the background. As you mention, they make for eye-catching nighttime shots, with that electric blue flare.

I bought mine used for $250, and have had great fun with it. The TL2 is the only APS-C format camera I own, and so ended up shooting exclusively with this most unlikely pair. More on that in the forthcoming article.

All the best,

Keith

Thanks Keith – makes sense that Photoshop is used for unsqueezing. Sounds like a good buy at $250. I got a used Mikaton 50 0.95 for about the same amount which is fun in the right circumstances but a bit of a one-trick pony. Glad I didn’t pay for a Noctilux!