The last week of December 1775 had weather that was almost identical to the same week in 2025. The wind howls in off the Delaware River. It’s freezing cold — too cold to snow in Philadelphia. Two hundred and fifty years later, my wife and I are visiting. It’s the first time we have been here, and a chance to see first hand some of the locations that have been immortalised in America’s history.

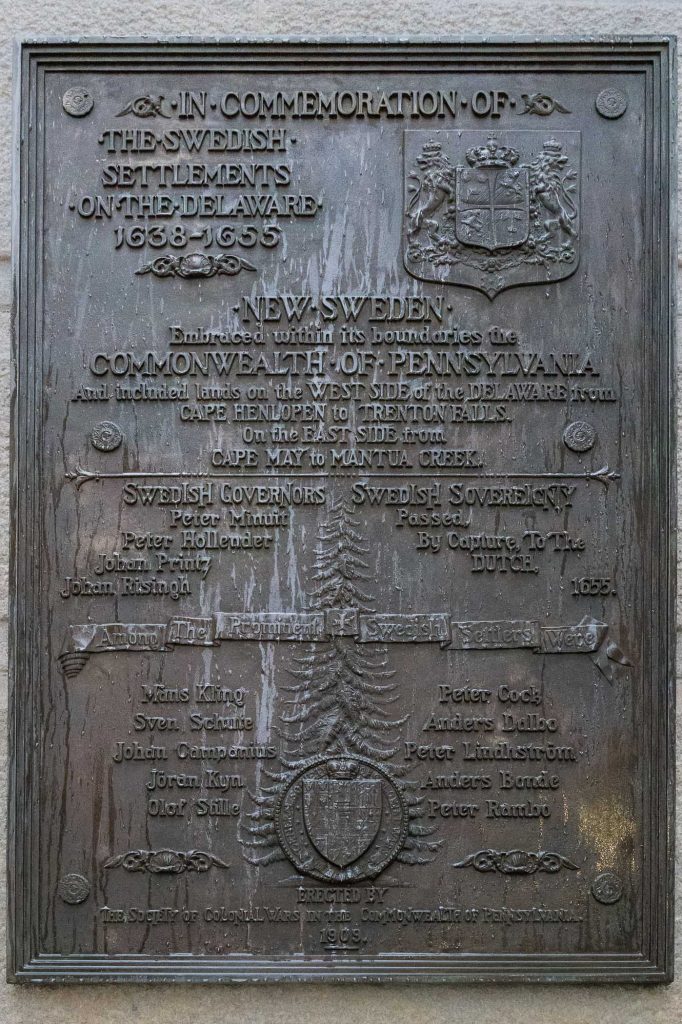

Philadelphia’s journey as an immigrant city is much older than this. “New Sweden” was a colony established between 1638 and 1655 on the Delaware River in what is now called “Society Hill”, part of modern-day Philadelphia. It was an expansionist part of Sweden’s “Age of Greatness”. And as a pre-echo the Swedish settlers were allowed their autonomy, militia, religion, courts, and land.

William Penn and the art of branding

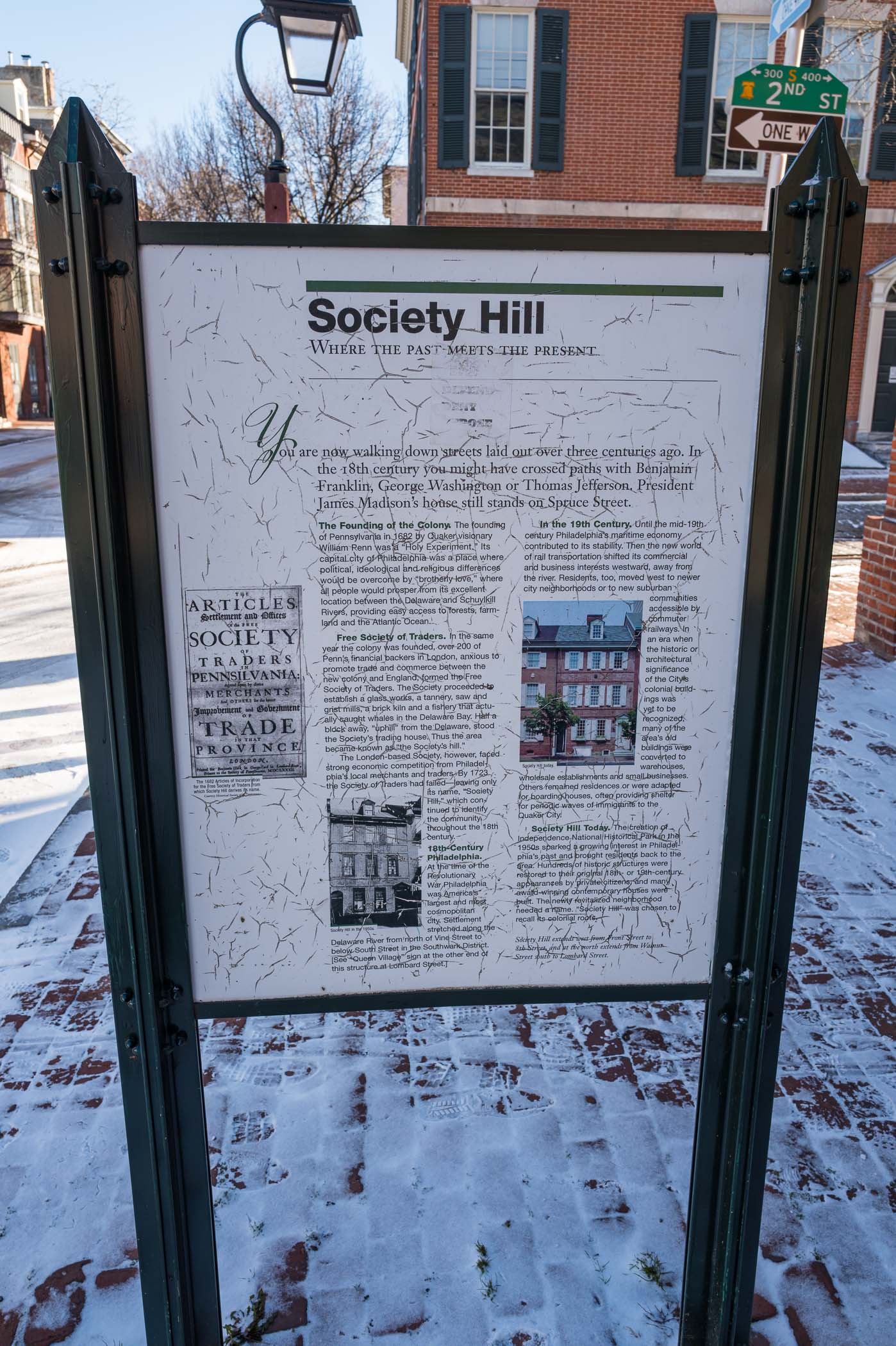

The arrival of the British brought William Penn, who founded Philadelphia in 1682. Penn had been given the territory of what would become Pennsylvania as a gift by the “Merry Monarch” King Charles II. He envisioned a city of religious freedom, wide streets, and green spaces, naming it for “brotherly love” (Greek: philos+adelphos). Today, Philadelphia is still known as “The City of Brotherly Love”.

Penn’s plan featured a grid system with squares and tree-named streets, attracting diverse settlers. By 1770 it was America’s leading city. By the time of the Revolution, over 150,000 Scots-Irish migrants from Ulster had arrived. Many of them came as indentured servants or “redemptioners” and 75,000 Germans had also arrived and had begun to settle.

Tripping over history

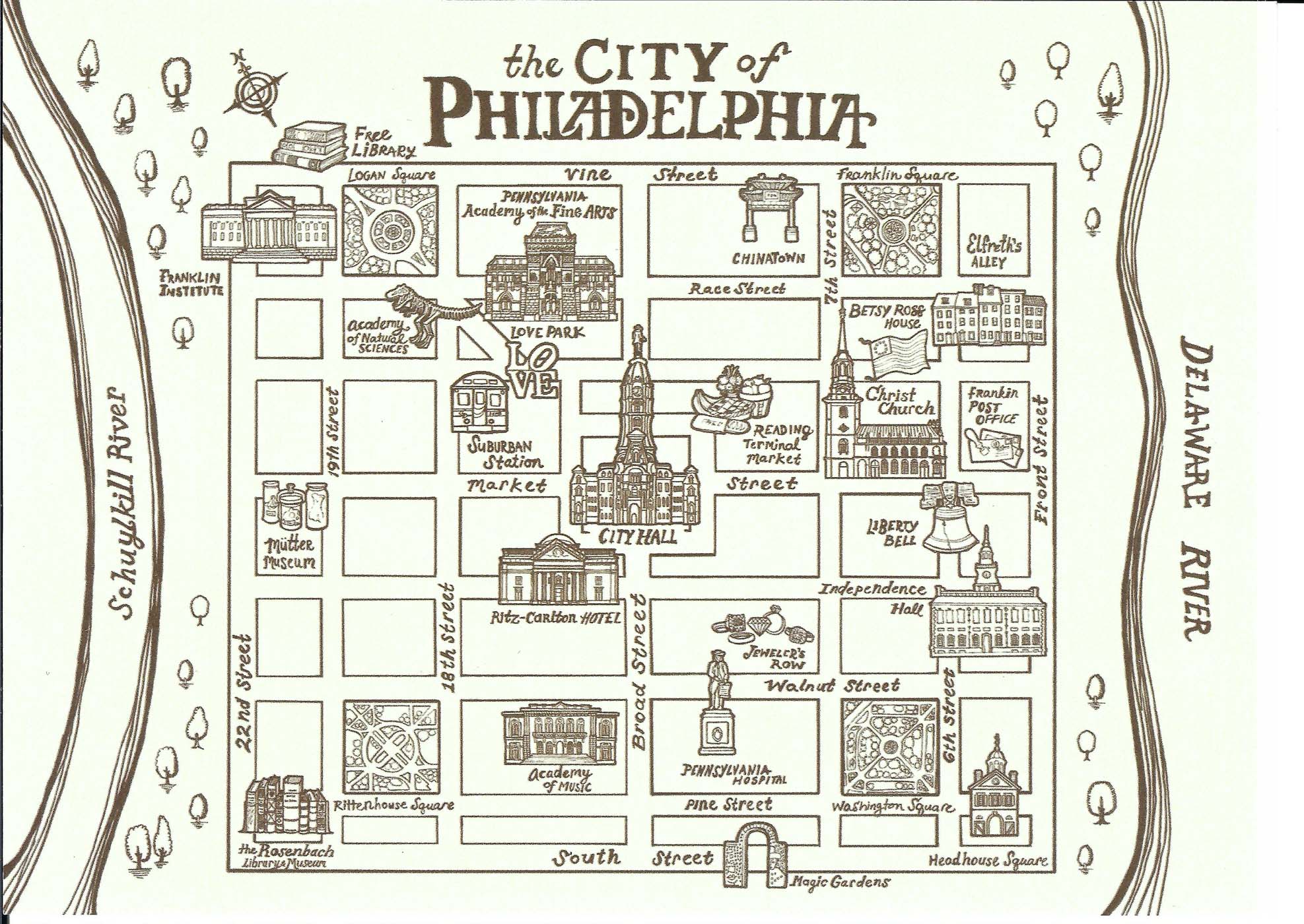

Philadelphia is the “Zelig” of American history. Wherever you look in the old part of Philadelphia (which is where we were staying, and shown in the postcard map above) you trip over history and see it emblazoned on plaques, old homes, and public buildings. You cannot ignore Philadelphia and hope to understand American history and why it is the way it is.

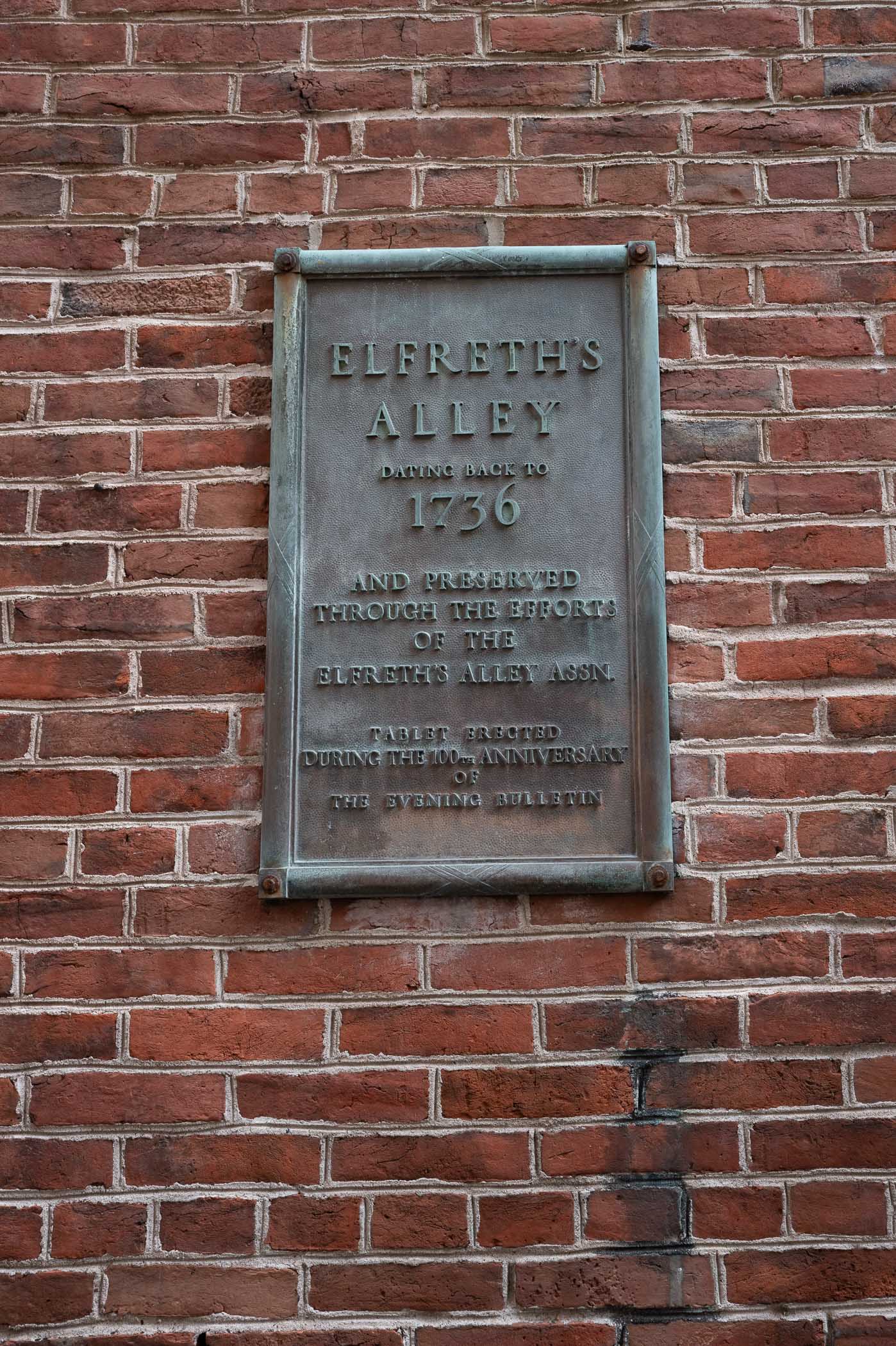

In 1703 Arthur Wells and John Gilbert created a narrow cart path between their properties, which extended from Front St. to Second St. The area was already overcrowded with rental properties that enabled traders to have as easy access as possible to the port. The path became known as Elfreth’s Alley, after Jeremiah Elfreth, who was a local blacksmith. It is the oldest continuously occupied street of row (terraced) houses in the USA, dating back to 1736, and was outside the original plans for Philadelphia.

December 1775

In late December 1775, Philadelphia was a bustling city of thirty to forty thousand people at the heart of the 13 colonies. The Second Continental Congress was meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) with the political goal of trying to develop a unified form of government.

They were also having to sustain the Revolutionary War effort. To fight back against the British, the Second Congress needed a standing army and navy. They lacked the means and the money to obtain goods to feed and clothe the troops, and the ships and boats to defend the Delaware River from naval attacks by the British.

The enemy at Philadelphia’s doorstep

At the same time, the Congressional delegates were debating strategy in city taverns like London Coffee House and City Tavern. All the while, the calls from “Americans” for independence continued to grow.

News had arrived that the American attack on Quebec on New Year’s Eve had failed. The Olive Branch Petition to the King had also been rejected, and hope for reconciliation with the King and Britain was fading. The ongoing hostilities were shifting sentiment, with some members moving towards the idea of full independence.

The cry for independence

The first edition of The Plain Dealer newspaper was published across the Delaware River in New Jersey on December 25, 1775, and reflected the growing political debate about independence. Thomas Paine’s influential pamphlet, Common Sense, was published in January 1776, further impacting public opinion and forcefully arguing for independence. If you were already living in America, were you going to support continuing being part of Britain, or were you going to support American independence?

The urgent need for consensus

Imagine, while you were contending with the freezing cold of a winter in Philadelphia, how could you organise an army made up of a mix of Scots-Irish and Germans, along with the English and Welsh settlers? Much of America’s early political blueprint can be understood in the context of this population mix and their disparate needs and wants.

The bells!

By September 11, 1777, Philadelphia, the revolutionary capital of America, was defenseless. The city was preparing for what was believed to be an inevitable attack by the British Army. One of the preparations was to remove the Liberty Bell and other bells from Philadelphia churches because bells could easily be recast into munitions and used by the enemy if the city was captured.

The bells were sent by heavily guarded wagon train to the Zion German Reformed Church in Northampton Town in what is now Allentown, where they were hidden under the church floorboards during the British occupation of Philadelphia. The Liberty Bell remained hidden in Allentown from September 1777 until its return to Philadelphia following the British retreat from Philadelphia on June 18, 1778.

Signs of history are everywhere

Like cities around the world, Philadelphia honours its history with wall plaques to remind you how important this city was to the birth of a nation. Sadly, the wall plaques in George Washington’s home that depicted the lives of some of his slaves have recently been removed on the orders of the White House.

Art is everywhere in Philadelphia

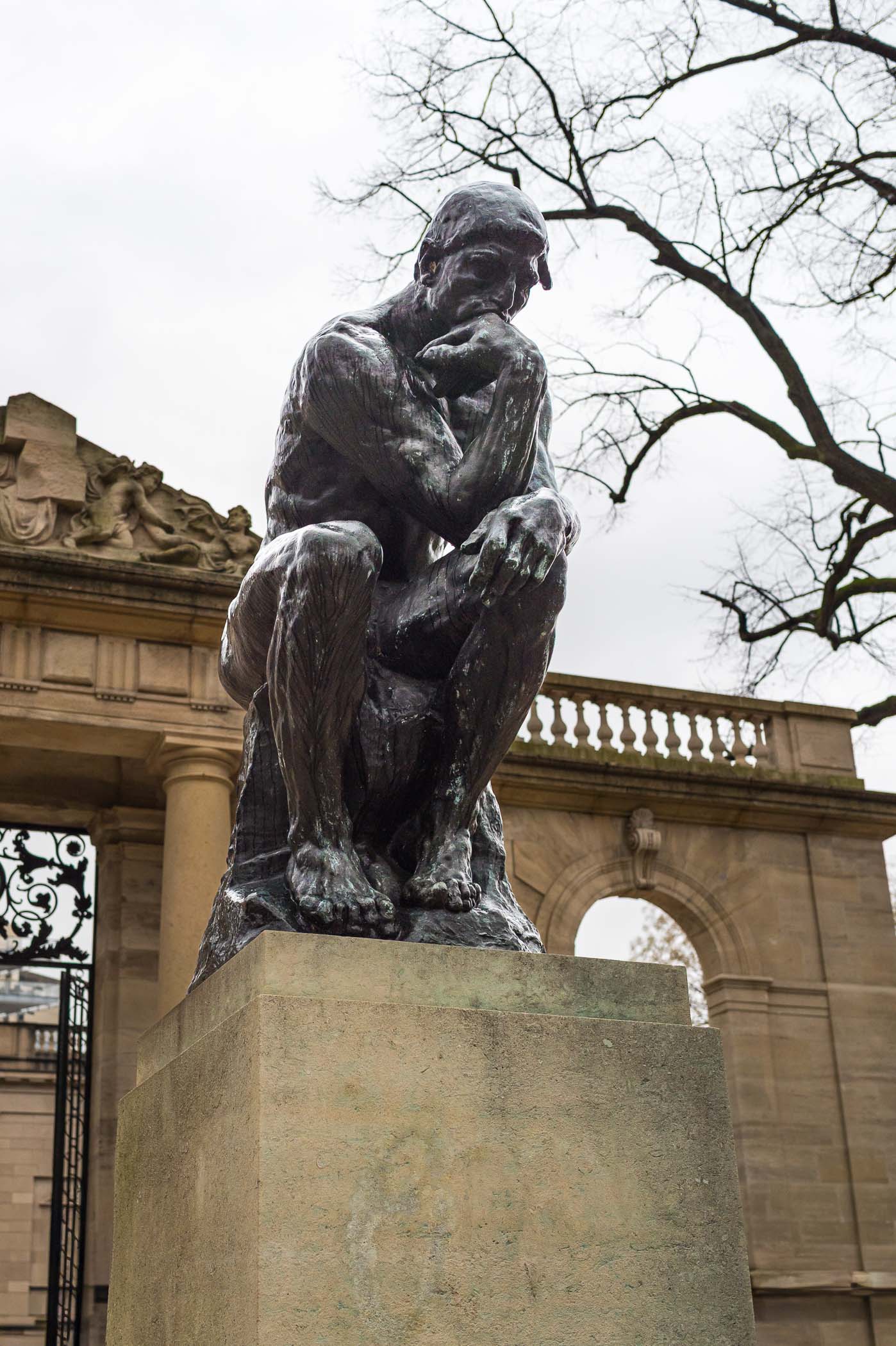

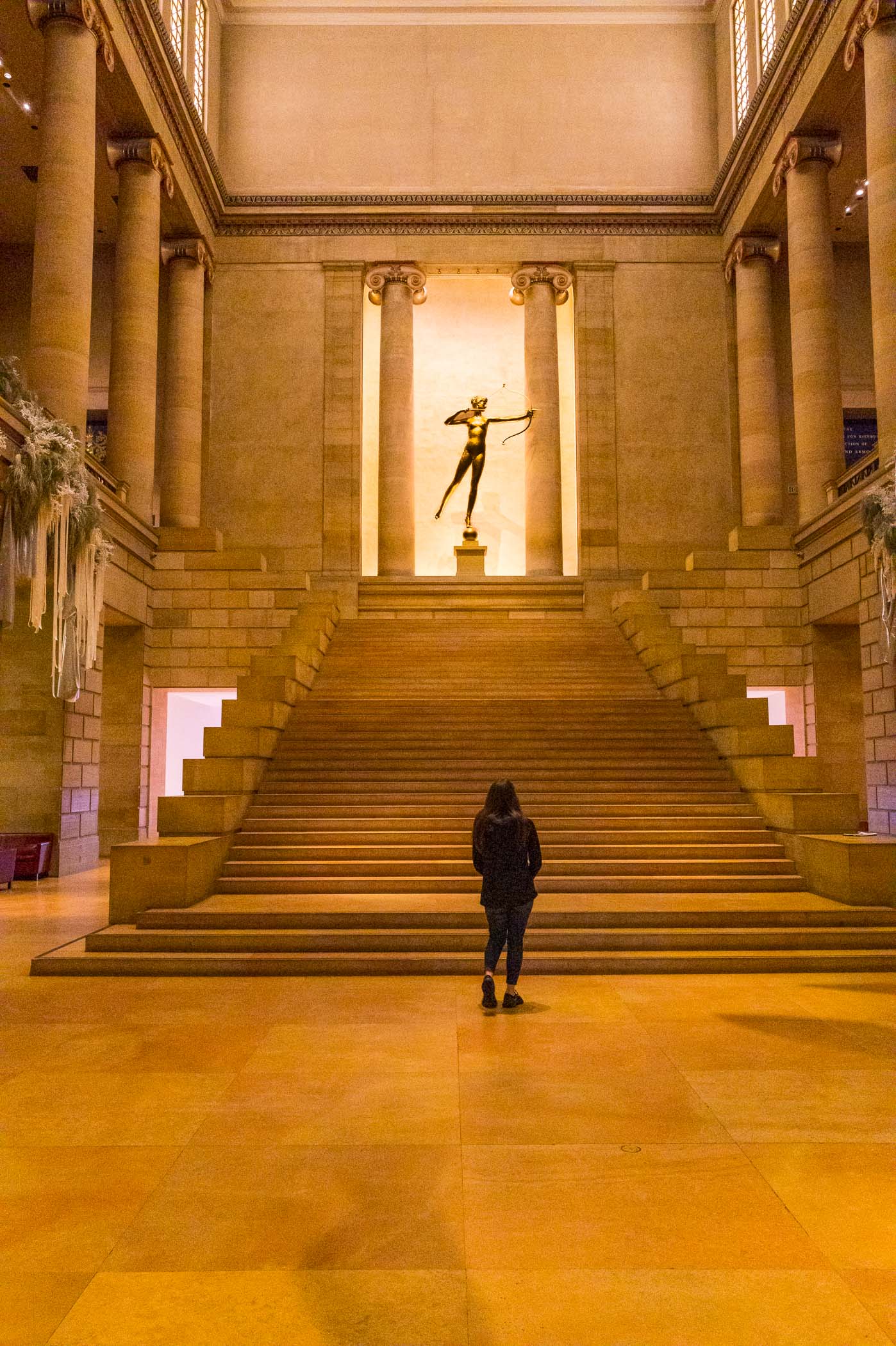

A walk along Franklin Parkway takes you to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, past the Rodin Museum, and the eclectic Barnes Museum. All well worth taking the time to visit.

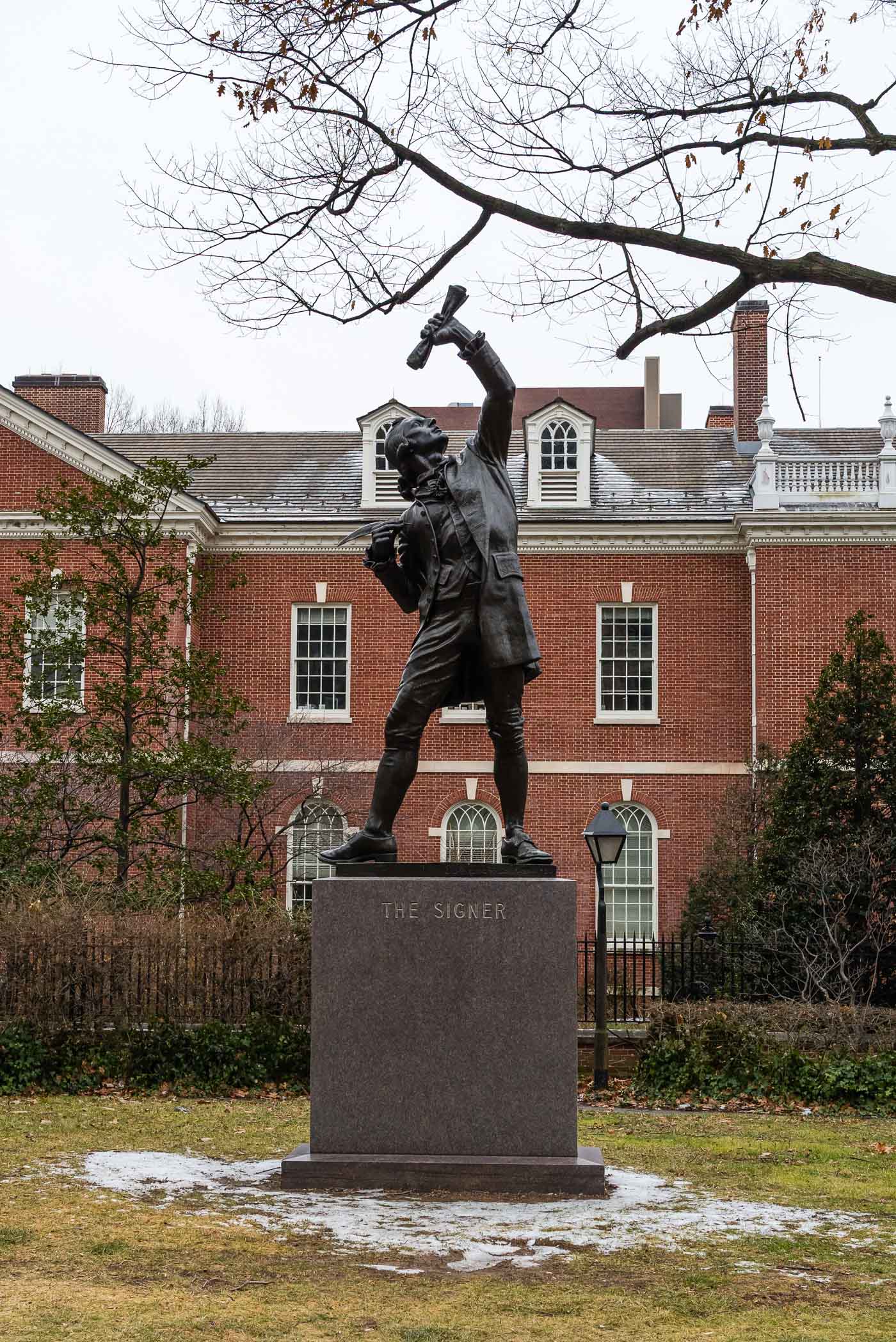

More of Philadelphia’s iconic public art is visible in the city wherever you look: from Rodin to Banksy lookalikes, to quirky sculptures, to sobering memorials to the fallen. One of the advantages of getting in your daily 10,000 steps, is that you get to stop and look at the art that’s on display in the city. Consider that a good bonus!

Rocky’s place in the City of Brotherly Love

Today, Philadelphia is more than just history. Anyone who has watched one of the “Rocky” movies will have seen the steps leading up to the outstanding Philadelphia Museum of Art. The city is also the fictitious home of the TV series “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia”. As you might surmise from earlier remarks, the title contains a substantial amount of irony.

Popular culture in Philadelphia, you can embrace

Walk past JFK Plaza and Love Park with its iconic sign, and step into City Hall, where the rooftop offers spectacular views. And that’s before we discuss the appeal of the Philly Cheesesteak. Prepare yourself for sliced beef, slathered with melted American cheese, sautéed onions and peppers, on a crusty Hoagy Roll. Delicious in moderation, but remember to snort a crushed statin if you wish to progress further.

There are museums that detail the city from various aspects of its growth. The birth of democracy, the Declaration of Independence, the Liberty Bell, and of course, the American Constitution. And a city that also saw the arrival of slavery. All of this is jammed into a small area of old Philadelphia. You will never get to see it all in five days. But that’s an excuse to return when the weather is warmer.

A new year begins

The late night fireworks light up the city and the Delaware River, almost as that attack by the British must have done 250 years ago. The celebrations continued long into the freezing cold night, and sometime shortly before dawn. It’s now New Year’s Day, January 1, 2026. We are 250 years on from the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, and the beginning of the formal separation of America from Britain. Five days in Philadelphia was not enough to really understand the complexity of what took place and what caused it. Thankfully, that relationship was patched up and continues to survive despite the odd rocky patch.

But what about the kit?

One of the challenges of a short trip is what camera kit you take. The temperatures were below freezing all day, every day. There was significant windchill, which tried to peel the skin from your face and any exposed extremities. Daylight was in short supply, and how much kit do you really want to carry, while pondering which lens you should use. The answer is simple.

I chose what now feels like my Old Faithful — my Q3 28mm. It’s wieldy and familiar, with a mostly wide enough field of view to capture city landscapes. Cropping from 60MP is easy. The lens is a gem. Exposure is good out to 25,000 ISO. All you have to worry about are a darkening EVF, either from the cold, or the early arrival of sunset, or from a declining charge in the battery. And yes, I always carry a spare, and charge the working battery in the camera with the cable.

The next trip will be to London for the LSI meeting in May, and another city saturated in history wherever you look.

| More: | |

| Philadelphia | American Revolution |

| Independence Day Coronado style | Leica Q3 Review: Solid upgrade for the perfect travel camera |

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

I have been to Philadelphia a couple of times since my last employer, before I retired was based there. As I might have said a couple of days back, they are no longer in business, although their ultimate owners are still very much so. The business model died with the ending of printed newspapers and their colour supplements, they used to offer collections of all sorts of trinkets, the most famous one here in the UK being ’The Spice Village’, spice jars shaped like houses, which some people would line up on a rack in their kitchens. All a bit kitsch really, but it paid my wages!

That company is called Brown-Foreman and among other things they make whiskey Jack Daniels, Southern Comfort and many others worldwide. They also sponsored sporting events like horse racing (Kentucky Derby) and boxing, they introduced the world to the then Cassius Clay. I remember meeting Owsley Brown who came to visit us in the UK, he had a thick southern drawl, but for such a powerful man, was really quite personable with a hearty laugh.

Oh, and one thing that amused me, was that I forgot to pack my razor the first time, so I asked a clerk in the hotel, where I could obtain one. She pointed to the door and said, just up the road opposite, so I set off and about an hour later walking over rough grass, I reached the Langhorne mall, found a good shaver and just another hour later arrived back at the hotel, completely worn out… I had already spent many hours in flight across the Atlantic. I think the clerk assumed that I was mobile, since everyone else in America is. 🙂

Thanks, Stephen,

I’m well acquainted with Brown Foreman both on a product level and also on a company level, as I worked with someone from the Brown family a few years ago. Plenty of good stories still to be told!

Cheers!

Jon

Thank you for this beautifully written and richly detailed reflection on the historical tapestry of Philadelphia. Your article captures the city’s stories, landmarks, and enduring legacy with both clarity and appreciation, inviting readers to see history come alive in everyday spaces. I particularly appreciate how you weave observation with thoughtful context, making the piece both informative and engaging for anyone interested in culture, heritage, or urban exploration. This post is both enlightening and inspiring, offering a meaningful reminder of the depth and character that history imparts to the places we inhabit.

A nice piece Jimmy, I too was given the tour, Liberty Bell etc., I also wanted to see the deli, where a mafia hit had taken place (I can’t remember who), I bought a tub of freshly made pesto, which was served at a lunch hosted by John Gianpolo, who was my main contact when I was at work, I talked to him every day for several years, as he practised the guitar that he had bought in London and I was showing him around.

Apparently, although they were made in America, they were considerably cheaper in London’s Tin Pan Alley. Willie Nelson’s guitar ‘Trigger’ came from the same Soho shop.

Many thanks, Jimmy, for your generous comments! I enjoy writing articles like this where you can weave together facts and observations. More to come!

Best

Jon

The last 6-8 years December was pretty mild in Philadelphia but December 2025 was the coldest one since 2010. I hope you were still able to enjoy the city though. And some belly-warming food like a cheesesteak was definitely recommended I would say. Were you able to visit Eastern State Penitentiary (with Al Capone’s cell) as well? You were close, it is about half a mile from the Rocky statue.

Thanks for your comments. We enjoyed the whole experience of being in Philly and the weather was not a big deal as we live in Chicago. We miss timed the trip to the Pen and were going to get there after it closed, with the next day it was closed for the Holidays. Next time!

Let me know if you are ever around again. Perhaps we can do a Leica CL shootout 🙂

I would like to return to Philadelphia as there’s a lot more to see, including the prison!

Cheers!

Jon