Click here to leave a comment on this article

Two months in and I love my Leica Monochrom like no other. Whatever is said about the restrictions of black and white or the excessive cost of this camera, the fact is that the MM is unique1 and a classic in the making.

For a month this summer I used mine almost exclusively for street photography in the Greek islands. It never failed to surprise me with its abilities and with the image quality and detail. I was nervous about committing a whole month to a black-and-white camera, especially in the colourful Cyclades with their unblemished blue skies and the greeny blue Aegean lapping at every rock. But the Monochrom has been thoroughly addictive and I haven’t felt at all short changed. On the contrary, I have been emboldened and enthused.

So, after four weeks abroad and two full months with the Monochrom this is a good moment to take stock of Leica’s unique black-and-white M as a photographic tool.

Before getting down to detail I should warn you that this article represents my personal views and experience with the Monochrom. It is subjective rather than technical and you will find more detailed expert opinions from photographers such as Ming Thein, Thorsten Overgaard, Jonathan Slack, Steve Huff and Andy Hendriksen at The Photoblogger. However, I hope you find my real-world experiences of use.

Build Quality

The MM, in common with all modern M models, is constructed mainly from brass. It feels like it: solid, dependable and indestructible. All the controls shout precision and work perfectly (including those on the lenses, which is a story for another day). The camera is finished in a stealthy matte black which is entirely unobtrusive and forgettable. That’s a good thing as any Leica owner will tell you. It is too early to say whether the paint will rub off at edges and points of wear to reveal the brass. This has happened to my old MP and I rather like it. I suspect a bit of brassing adds to value rather than detracting.

Ergonomics

Ergonomically and mechanically the MM is identical to the M9 (or, perhaps more specifically, to the the M9-P which shares the same sapphire-glass screen and stealthy image). It feels exactly the same and, to my mind, is all the better for that. The new M (Type 240) is a tad thicker and 15 percent (90g) heavier. I notice this extra bulk and weight in the M and it was a pleasant experience to get back to the more svelte lines of the MM.

With its restrained finish the Monochrom is a real Q-car of a camera. The only indication of origin is the “Leica Camera Made in Germany” engraving on the back (and without a white inlay it is invisible from more than a few inches away) and the “Monochrom” legend on the hot-shoe. There is no Leica dot, red or black, and only those in the know will recognise this camera for what it is. For once, unlike with the comparatively gaudy Leica M, I have not had to reach for my roll of black gaffer tape.

The Monochrom is a comfortable camera to hold and many owners will be happy using it naked without grip or case. For test purposes, I have had the opportunity to experiment with various added-grip options. I found an old M8 grip on a top shelf and also remembered I had held on to the Thumbs Up hot-shoe mount I bought for my M9 from Tim Isaac at Match Technical. As a result, I have been using both in tandem. They work well together but using two is probably overkill. On balance I will retain the Thumbs Up and put the M8 grip back on its shelf. This choice is based mainly on aesthetics since the M8/M9 cylindrical grip is rather odd and ugly to my eye. I am currently in the market for a leather half-case and will be reviewing all good-quality options on the market.

Unlike all other digital cameras (as far as I am aware), Leica Ms require you to remove the brass bottom plate (with one quick-release screw) for access to the battery and SD card. While this arrangement is often criticised as old fashioned (it follows the practice used on Leica’s film cameras) I much prefer it to the modern flappy cover that is often flimsy and hard to secure. The removable bottom has other advantages. When you buy an accessory grip it comes with a replacement bottom plate so that the grip adds nothing to the height of the camera. This is not an insignificat detail because most grips will add at least 75mm to the height of the body.

The MM shares its 1800 mAh battery with the M9 which is useful to know if you currently own an M9. The new M240, however, adopts a larger and incompatible battery.

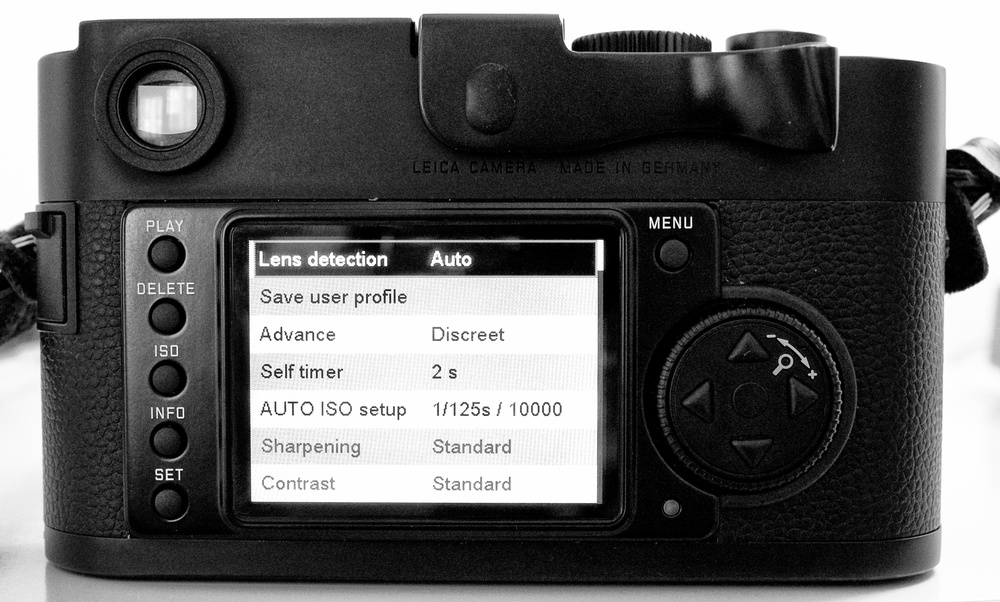

Controls

Controls on the MM are pure M9 and the menu is solidly Leica, simple and without a multitude of confusing sub menus. I have read complaints that Leicas menus consists of just one scrollable list. But I much prefer this approach to the Byzantine complexity of modern menus on even the most consumer-orientated point and shoot. There is no white balance control because it isn’t needed; other than that it is business as usual.

The MM shares with the M9 the much-liked “discreet” shutter release setting. When selected, holding down the shutter release after taking a picture delays the recocking noise until the finger is released. So you can take an almost silent picture, turn the camera in another direction and release the shutter. It is indeed discreet and I prefer it, particularly in the street. Sadly this good idea was not carried forward to the new M240.

Almost as an afterthought I should mention the word rangefinder. I cannot imagine many people will be buying the Monochrom without prior experience with a Leica, whether a film camera or digital. So it is tempting to assume everyone knows about the focusing system. However, for those new to Leica, a few words of explanation. The Leica finder window offers a big, bright optical view of the world combined with a mechanical focus system based on the convergence of the view from two windows mounted on the front of the camera. A central square in the frame is used to converge the two images. When this happens, provided lens and camera are both properly calibrated, you have perfect focus. Bright framelines are used to represent the field of view with any particular lens and these come in pairs (35/135, 28/90 and 50/75) and change depending on which lens is mounted.

In my view the rangefinder system is best for manual focus in good lighting conditions. It is less than ideal in poor light because of the lack of contrast. Advances have been made in recent years with improve manual focus when using electronic viewfinders, including the focus peaking system used on many modern cameras, including the new M. Focus peaking, where the area in focus is highlighted in a contrasting colour, is effective but not as easy to use as the old Leica rangefinder. Tellingly, although I have an optional electronic viewfinder on my M (240) I seldom use it for lenses between 28mm and 50mm. On balance, I prefer to use it on 75mm and 90mm because of the relatively small framelines for these lenses in the rangefinder. For lenses wider than 28mm, of course, the EVF (or an accessory optical finder) is essential on Leica M cameras.

The main disadvantage of the system is that it is mechanical and therefore subject to misalignment if abused. Leica offers to recalibrate lenses to your particular camera body at a price (and at the factory in Germany) but I have not so far found this necessary.

Leica’s rangefinder implementation has always been one of the best and I still see it as a major asset rather than as a throwback to earlier times. It is the essence of the camera. For a brief moment, I suspect, Leica’s designers even considered replacing the rangefinder of the M240 with a modern electronic unit. But only for a moment because the resulting camera would not have been an M.

.jpg)

As with the M9, there is a dedicated ISO button which allows quick changes to sensitivity from 320 right up to a whopping 10,000 (unlike the M9, the MM copes well with such high ISO). And again as with the M9, the SET button allows quick adjustment of file format, exposure compensation, exposure bracketing and selection of user profile. Base ISO is 320, although there is a “push 160” option which I have not found useful, and an auto setting (for which you can select maximum permitted ISO and minimum shutter speed using the main menu)

Apart from the lack of white balance control, the MM will be totally familiar to the owners of either the M8 or M9. You have controls for what you need and nothing more. Access to the most frequently used adjustments is instantly available via the SET menu.

Sensor

The Monochrom is all about the sensor. The camera has a similar Kodak CCD sensor to that in the M9. The big difference is the removal of both the anti-aliasing filter (now a fashionable trend among high-end colour cameras such as the Nikon 800E and Sony RX1-R) and the Bayer colour filter. Thus stripped and tweaked, the Monochrom’s sensor can concentrate on tone rather than colour. Every little pixel does its monochrome duty without the complication of having to kowtow to the god of colour. The result is sharply enhanced dynamic range and remarkable sharpness.

While this sensor has a relatively modest 18 Megapixels (similar to the M9), the concentration on tone rather than colour means that it can fight its corner with much denser colour sensors. Some reviewers have said that it is equivalent in resolution to the 36.3MP of the Nikon D800E and I cannot dispute this. Although it is a subjective view, I certainly believe that the MM can comfortably outperform a 24 or even a 30MP colour sensor.

Exposure

Exposure metering on all Ms is rather primitive when compared with the systems available on the majority of modern bells-and-whistles digital cameras. You have centre-weighted exposure and that’s that. Having been used to Ms for some years I find this no problem and it is something you soon learn to appreciate. If anything, it encourages the owner to experiment with fixed manual exposure settings as I learned recently at the Leica Akademie. For street photography in particular, pre-set exposure works well.

Digital Ms are essentially manual cameras. The only nod to automation, other than exposure metering, is the ability to set the shutter speed to automatic. This is the same set-up used on the M7 film camera. With a specific speed selected instead of using the A (auto) position, a simple system of two inward pointing arrows and a central dot in the rangefinder window is used to indicate exposure. When the central red dot appears you have what the camera assumes to be correct exposure. The arrows at either side of the dot guide you to this point by indicating the direction you need to turn either the aperture ring or the shutter dial. It is very simple once you get used to it and, I feel, this very simplicity in the M is one of its greatest virtues.

The Monochrom deals with over and under exposure in a slightly different way to most digital colour cameras. In general it is all too easy to over-expose lighter parts of the frame when exposing for a darker subject. With a colour sensor you can often recover over-blown detail in post processing but you will have little luck with the Monochrom. The colour channels of a Bayer filter are much more forgiving and highlights can often be recovered successfully. It is thus better to err on the side of under-exposure with the MM. Crucially, impressive detail can be recovered from darker areas of a Monochrom file. I prefer to expose to the left of the histogram and avoid the right wherever possible. Manual, average exposure setting is often a lifesaver, especially with backlit subjects.

A word of warning on exposure compensation. One evening I was fiddling with the menus after a couple of glasses of wine and decided to change the option to allow exposure compensation from the knurled ring around the four-way controller on the back of the camera. By default you have to enter the SET menu to change compensation. I immediately forgot I had done this and went out the following day to bag over 130 shots. Only later did I find them all over exposed (a cardinal sin for Monochrom wielders). I had inadvertently moved the setting ring to +1-2/3 EV while holding the camera. There is a warning of exposure compensation in the viewfinder but it takes the form of a flashing red comma in the speed value and is easily overlooked if you don’t know what you are looking for. I had not noticed this at the time but I am now keenly aware of it.

There are three options for exposure compensation adjustment. The default, safe option is to allow adjustment only through the SET menu. The extreme is to allow adjustment simply by moving the setting ring encircling the four-way controller. This is the easiest for quick changes if you know what you are doing and are prepared to keep a close eye on the viewfinder display. The third option, which I currently prefer, is to permit use of the setting ring but only in conjunction with a half-press of the shutter release button. Although a little awkward at first, this soon becomes second nature. All you have to be aware of is that, since there is no physical exposure compensation dial to check (as on many cameras such as the Fuji X series and Sony RX1), you need to keep a close eye on the viewfinder speed setting to detect the warning blink.

.jpg)

Screen

In a £6,000 camera you could be forgiven for expecting a state-of-the-art rear screen such as you might get on , say, a £300 compact. You would be wrong. The tiny 230,000-dot viewer is pure 2003 vintage and absolutely hopeless in checking shots, which invariably look depressing. In this, the MM shares the heritage of the M8 and M9. Only the new M gets a better screen with live view. However, since the CCD sensor in the MM does not support live view the screen is of relatively little use other than for accessing the menus or checking the full-width histogram. In this it is adequate and the size of the histogram is ideal for the M instead of the mini version seen on the M9 and M-E. Chimping with the MM is an wholly unrewarding experience. It is far better to leave this until you get your shots uploaded to a computer.

Despite these excuses, the screen of the MM (and M9/ME) is a disgrace and I have never understood why the resolution, if not the size of the screen, has not been upgraded. Perhaps the low resolution is a restriction of the firmware design but I would need convincing.

ISO Performance

The M9 struggled with high ISO and, frankly, it was a brave soul who ventured above 1600 without serious noise penalties. In contrast, the removal of the Bayer and AA filters coupled with behind-the-scenes sensor tweaking has transformed the MM into a camera with a very useful ISO range. This is acknowledged by Leica in providing an available range from 320 to 10,000 (the M9 tops out at 2,500). In my experience, although low light testing has not been a priority, 3,200 and 6,400 settings are perfectly usable and even 10,000 is possible although noise is by then becoming obtrusive and the results rather grungy. The good thing about noise with the MM is that it more resembles film grain rather than traditional digital noise. Using higher ISO is a valid technique to achieve film-like qualities and some of the results can be impressive.

Filtering Question

Several reviewers have mentioned that it is advisable to employ colour filters with the MM, arguing that the sensor behaves in a similar way to film. I had no filters to take with me to Greece so I have not been able to prove or disprove that theory. I have now acquired a Zeiss mid-yellow filter and will give it a run. Up to now, though, I have been perfectly happy with the output from the MM, sans filters (other than the usual lens-protecting UV).

RAW processing

I expose exclusively RAW (DNG) files and do not bother with JPGs out of the camera. However, the OOC DNG files are distinctly flat and cry out for post-processing before the high level of detail and tone can be extracted. To some extent this applies to RAW files from any camera but the MM is particularly picky. For this purpose I have found Silver Efex Pro (bundled by Leica with the MM for very good reasons) to be excellent. Even the preset filters available in Silver Efex allow a high degree of customisation without the need for extensive pp knowledge. I find that they are an invaluable start to pave the way for final tweaking.

Lenses

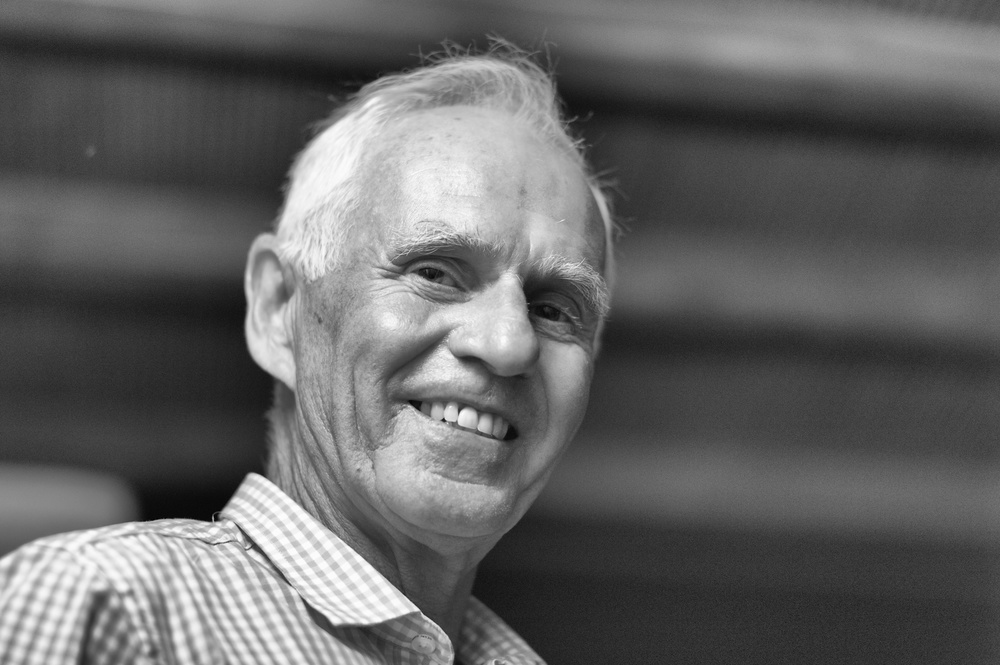

While this is not strictly relevant to a review of the camera itself, a few words on lenses is helpful. Before leaving London for the month I had a choice to make and decided to pack light. I chose a 35mm Summicron (instead of the heavier ‘Lux), and one of my favourite lenses, the 75mm APO Summicron. I should have left it at that but at the last minute I got cold feet and threw in a 50mm ‘Cron and my ancient 90mm Tele Elmarit, the latter on the grounds that it is tiny and very light and might come in useful. (Note for non-Leica users: Lens names usually indicate the maximum aperture. Summiluxes are all f/1.4, Summicrons are f/2, Elmarits are f/2.8, with others such as Summarit and Elmar indicating a range of maximum apertures)

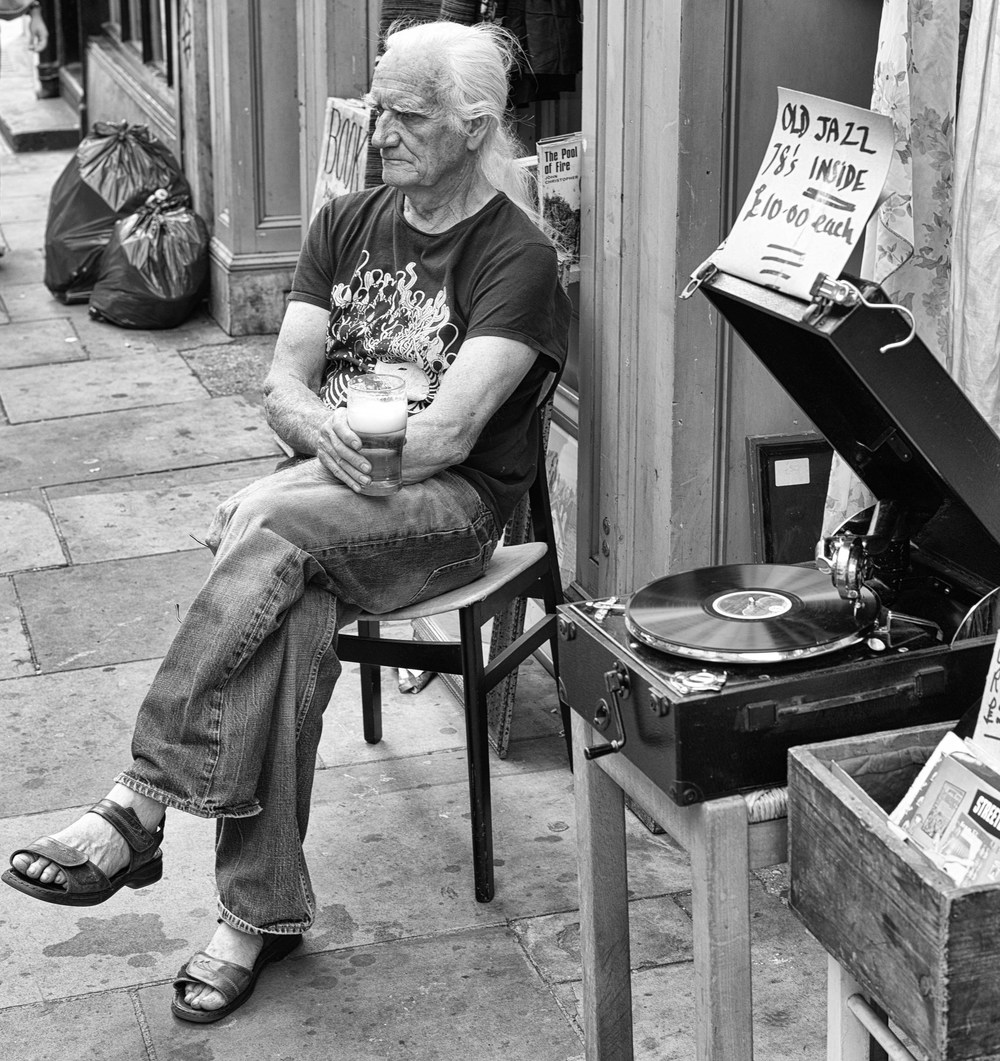

In practice I used the 35mm and 75mm almost exclusively while away. The 50mm is too near to both of these lenses and I felt no pressing need to use it. Similarly, the 90mm offered little advantage over the 75mm. Both the 35 and 75 Summicrons are wonderful lenses. The 75 ‘Cron is pretty ideal for portraiture in my view (although popular prejudice runs to 90mm or longer) and also performs well in street photography when you prefer to be a little further away from the subject.

The 35mm ‘Cron is the ideal general-purpose lens for street photography and it acquitted itself well in the narrow streets of Mykonos town. On a couple of occasions, trying to shoot buildings on the other side of a two-meter-wide road, I wished I had brought an even wider-angle lens. All things considered, I was happy with my choice and, in retrospect, I would have been better leaving the 50mm and 90mm at home.

In my experience it is wise to marry a 35mm with a 75mm for lightness when travelling. Alternatively, 28mm, 50mm and 90mm lenses provide a good range without excessive proximity in focal lengths. I now regret selling my 28mm Elmarit earlier this year. Never sell a Leica lens is a good motto because they invariably rise in value over time. Also invariably, as soon you sell one you wish you hadn’t.

Ownership

The MM is a deeply satisfying camera to own and use. As a successor to the M9 it is well-tried mechanically and exhibits few quirks in use. It does share foibles with the M9, chief of which is a slow write time. The blinking red light is a common sight and on some occasions, for no good reason, a shot takes a painfully long time to write to file and the camera is out of action until this has finished. It is a slow camera, no mistake, and newcomers from more modern devices will be surprised. You just get used to it. The MM, like all Leica Ms, is not a camera for rapid shooting, for sports or for action. But stay with street photography, landscape and portraiture and you have perhaps the best tool in the world.

After two months the MM is now my takeaway camera of choice. It is the one I am most likely to pick up in the morning and it is one that gives me more pleasure even than Leica’s flagship M 240.

My main photographic passion is street work, mostly here in London, but I like to carry a camera wherever I go. Portraiture is my second love, followed by landscape a distant third. For me, the Leica Monochrom is the ideal photographic tool. For street work it ticks all the boxes: A discreet, non-threatening appearance, a wide variety of superb lenses and excellence in manual focus, especially zone focus. Slap a 35mm lens on the MM and you have the archetypal street camera. I do not miss autofocus because, in street work, even fast autofocus can be bamboozled. Instead I prefer to pre-focus, or zone focus, using the focus scales engraved on all Leica M lenses. With a small aperture (f/8 is ideal for street work in daylight conditions) a 35mm lens gives a usefully wide depth of field.

The f/2 Summicron 35mm is my ideal lens for street photography and I prefer it in general use to the faster, heavier f/1.4 Summilux.

Digital rot

Digital rot is a consideration with all modern cameras (unlike, for instance, Leica film cameras which tend to go up in price). And, with a ticket price of over £6,000 on the Monochrom, there is a lot to rot. Strangely enough, though, Leica digitals fare better on the secondhand market than you would expect. You will lose money, especially if you buy new, but the Monochrom especially will be in demand for years to come. I bought mine secondhand, thus saving over 20 percent on list, and the few others that have come on the market are similarly priced.

Historically, German-made Leica digitals do quite well. Even the Japanese-made Leica compacts benefit by association. While Leica digital bodies are not inflation-proof like Leica’s film cameras or lenses, the secondhand market shows that values do hold up quite well in later years. The original M8 is still fetching £1,300 (or about half its original value) after eight years. The second-hand M9, after a brief hiatus following the introduction of the M240, is creeping back towards £3,000 while the more desirable M-P is still selling for nearer £4,000. Even the highly-esteemed ten-year-old Digilux 2 with its ancient 5MP sensor has a ready market at around £600, some 50 percent of the original cost. And that after ten years. It is obvious that there is a good market for Leica digitals and the loss can be minimised by buying secondhand as I did.

Conclusion

This is not a camera for everyone. It has a reasonably steep learning curve and and demands a knowledge of photographic techniques. And not everyone would spend so much money without the option of colour. Exposure can be fiddly and extra care has to be taken if blown highlights are to be avoided. But for the purist, the MM is an absolute gem and will surely delight.

The Monochrom was something of an experiment and Leica had no way of knowing whether or not it would succeed, especially at the pip-squeaking price. The bet has paid off and I think it is only a matter of time before we see other monochrome cameras reaching the market. Even removing the AA filter from high-end cameras such as the Nikon D800 (in the D800E version) was considered a bold step but is now spreading throughout the photographic world. The Sony RX1R just one recent example.

To remove the colour filter was considered by many to be a step too far. Who would pay all this money for a dedicated black and white camera when colour files can be converted so easily and so effectively? Against this background in May 2012, Leica’s further move was one shot too far into the dark. Yet critics are no longer laughing. The Monochrom will now surely be copied.

All that considered, the Monochrom is still a camera for the connoisseur and buyers will approach with caution and a fat wallet. For my part, I am convinced it is a rare gem and I believe the current MM will be a camera to keep. It has all the makings of a classic and is the nearest the Leica owner can get to the timelessness of film.

Read more of our camera reviews:

Fuji X and Sony A7 with Leica lenses

Voigtländer VM-E Close-Focus Adapter for Sony A7

Sony A7: Bargain basement quality zoom from Leica

Camera supplied by the ever-helpful and knowledgeable Len Lyons at London’s oldest Leica dealer, R.G.Lewis in Southampton Row. Thanks are also due to my friend George James for his photographic contribution and to the talented Robin Sinha who helped enormously during my recent visit to the Leica Akademie.

[1]: The adjective unique is often abused. Nothing can be almost unique or very unique. It is or it isn’t. I use unique advisedly in relation to the Leica Monochrom. It is unique on the current market. However, it is not the world’s first monochrome digital camera. That honour goes to the Kodak DSC 760M introduced in 2001. It was a brave try and had its adherents (see this review) but was killed off prematurely by Kodak. It is fitting that the Leica also sports a Kodak sensor, so it is really the spiritual descendant of the 760M.

Outstanding review. I’ve had my Monochrom for two months as well, and haven’t taken a color picture since.

Excellent write up Mike. Thank you !