So enthused have I been by the 56mm f/1.2 Fujinon lens that I went a whole month with the Fuji X-T1 without once mounting the M adapter and trying out a manual focus optic. Then, when I wanted to compare the legendary 50mm f/1.4 Summikux-M with the Fujinon 56mm in order to explore the new electronic shutter feature, I discovered some unexpected delights.

I always knew that the X-Series cameras performed well with Leica lenses. A couple of years ago I wrote about my experiences with the X-E1 and a few pieces of M glass. At the time my main problems came with the actual implementation of the manual focus system, given the lack of communication between lens and camera.

One of the big annoyances using manual lenses on today’s electronic cameras is fiddly focus. To activate focus magnification, which I find to be an invaluable aid, it is necessary to press a button, sometimes more than once if you have a choice of magnification. This has to be done before every shot. The ideal is to have magnification activated when turning the manual focus ring but this is an elusive goal.

The problem is that no modern camera (with the exception of the Leica M itself) has any inkling of movement in the focus ring. Not even Leica’s own APS-C offering, the T, can perform this trick. There are no electrical connections on manual lenses, so no information. This also leads to a lack of metadata, although Lightroom (at least) does make an effort to estimate aperture and, if you set the lens focal length in the camera (where possible) you get some help.

The M is the only modern camera that detects movement in the aperture ring; this is because of the venerable mechanical rangefinder mechanism which provides a physical communication between lens and camera. With the electronic viewfinder fitted to the M you can set the camera to enter magnification mode whenever you start to focus. This is undoubtedly very convenient and is one of the main advantages of using the electronic viewfinder on the M.

The Fuji X-T1 also has a trick or two up its shutter. For starters, there is a menu page for manual lenses with space for six focal lengths. The first four are fixed (21, 24, 28 and 45mm) and the other two are customisable. I am not sure why Fuji didn’t opt to make them all adjustable. For me, both 21mm and 24mm are redundant because I don’t possess any wide-angle Leica glass.

However, for all six options you can pre-set distortion and colour-shading correction as well as perpheral illumination correction. Inveterate fiddlers will love these extras although, for the purpose of my demonstation photographs, I left all settings at default. This manual-focus screen feature is common to all X-Series ILCs, not just the X-T1.

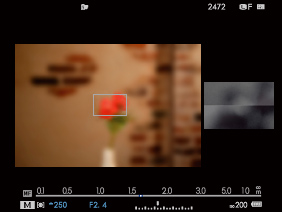

Then there is the new electronic viewfinder with its x0.77 magnification and impressively short 0.005sec lag. The finder is so large that there is room for two screens, a large composition frame to the left and a smaller focus screen to the right. This is an option; the full-frame combined view being the default.

This split view is quite addictive. For starters, the side focus window has a permanently enlarged view of the focus point from the centre of the main screen. Just move the focus point around on the main view to find the object of focus displayed in the small side screen. Secondly, combined with the intriguing rangefinder-like split-image function, focusing is remarkably easy. Check out the video below.

The entire set up puts me in mind of using an older Leica before viewfinder and focus windows were combined in the 1954 M3. My 1953 IIIf, typical of all Leicas from the early 1930s onwards, sports two tiny, side-by-side windows; one is for composing the picture, the other for rangefinding. The difference is that in Fuji’s huge finder you see both windows at once and, of course, they are so much bigger.

When I first tried the split-image focus on the X-T1 at Photokina I was less than impressed. I was conditioned to believe that a simulated display such as this could never equal a genuine Leica rangefinder. Ultimately I am still inclined to that view; but I can no longer dismiss the Fuji system as a mere gimmick.

Admittedly it works best when you can home in on a clear vertical line (as does the Leica system for that matter) but it is not as effective in lower light conditions as the optical system on the M. There really is nothing to compare with the bright optical image seen in the Leica finder.

The Fuji split-image system is also far less easy to use when viewing the full-size image on the rear screen of the camera or the viewfinder. Invariably I prefer to use the Fuji’s viewfinder with the two-screen option enabled.

In conjunction with the small focus window in the viewfinder this version of split-image actually works well. I find it speeds up the process of dealing with manual lenses as well as improving the hit rate for perfect focus. With no magnification button to press, focus is quick and precise, with the full frame always on view to the left. In short, I love it.

Nothing, but nothing can compare with the sheer mechanical pleasure of nailing focus on a Leica (or, for that matter, on many of the now-defunct older rangefinders such as the Contax pictured below). But Fuji’s simulation offers a remarkably close experience. It makes me want to use my Leica lenses more and more on the X-T1.

Autofocus has its place and, for instance, I find I get more precisely focused keepers when using a Fujinon lens for close-up street photography. Unless I use zone focus with a Leica lens, the opportunity is often lost while adjusting focus. Died-in-the-wool Leicaphiles will disagree, of course.

These advances made by Fuji in the manual focus capabilities of the X-T1 help enormously. I would say that using the split-screen set up on the Fuji is every bit as quick (in bright conditions) as when adjusting a true rangefinder. And that is quite an achievement.

It’s worth noting, incidentally, that the split-image finder is just one of the focus aids available to X-T1 owners. As on the X-E2 and X-Pro 1, you can opt for focus peaking. You also have the choice of dispensing with the second focus screen, reyling entirely on the main display. In this case, however, it is necessary to press the focus assist button before every shot if you want to see a magnified view.

Finally, you can turn off both focus aid simulations and rely simply on your eyesight and the slight shimmer, or moiré effect, which indicates when the subject is in focus. This is an optical phenomenon which appears to be common to all electronic viewfinders, not just Fuji’s. I’ve seen a similar effect with the Sony A7, the Leica T, X-Vario and others. In some ways I prefer this to focus peaking which I often find distracting.

Why use manual lenses?

With such a good arsenal of Fujinon glass at your disposal, you might well ask why bother with all this fiddling in order to use manual lenses. There are several answers to this.

The obvious one is that it makes a lot of sense if you already own Leica or Voigtländer optics and want to make more use of them.

It’s especially valid if you have manual lenses in focal lengths you don’t use often but would like a prime instead of making do with the Fujinon zoom. I also know that many Leica owners keep a Fuji X camera as a second body, taking advantage of the 1.5 crop factor to create a new focal length from favourite lenses.

More compelling, however, is the fact that manual lenses are so much easier to use and more rewarding than electronic lenses working in simulated manual focus. Fly-by-wire focus. as found on most automatic lenses, is extremely woolly in comparison with the precision focus on a true manual lens.

For starters, the focus ring of a Leica lens has a movement of no more than 90 degrees and there are clear stops at either end of travel. In most cases, with electronic lenses, the ring just goes round and round and, often, requires several complete circuits to get from near to infinity. After trying manual focus on an automatic lens you will probably end up going back to autofocus except for very specific tasks. If, on the other hand, you have tried manual focus on your Fujinon lenses you will be blown away by the precision of a manual-focus lens.

Using a true manual lens is a pure delight. The smooth and quick adjustment of focus is totally involving and immensely satisfying. A Leica lens on a Fuji X-T1 isn’t quite as rewarding as when it is mounted on a Leica. But with the new split-image system Fuji has done us proud.

I’d say there’s even a case for buying a Leica lens for the Fuji even if you don’t already own manual optics. It’s something very interesting to try and you will be impressed by the optical quality. Who knows, you might even end up with a Leica film or digital camera to go with that lens.

Fuji M Adapter

The Fuji M adapter is a very well-made and precise instrument that allows you to mount most (but not all) M-mount rangefinder lenses on any of the ILC Fuji X-Series cameras (X-Pro 1, X-E1/2, X-T1).

But is it worth the extremely hefty £170 price tag when you can buy a dumb (but well-made) Kipon device for £58 or an even classier Novoflex for under £70?

The Fuji device does bring what Fuji enticingly describes as “electronic contacts for communicating signals with the camera body” but this feature offers far less than it promises. At first I imagined this system might read six-bit coding on Leica lenses and automatically adjust the camera’s lens function to the right focal length. I was wrong. You still need to open the menu and select the appropriate focal length (as much for metadata purposes as anything else).

Sure, there is a row of ten impressive-looking little brass contacts on the adapter, but what do all these busybees do? Not much, actually. First, they tell the camera to “shoot without lens”, something that you can set up in the menu in any case. Even when it is switched on in the menu it doesn’t prevent the use of automatic lenses, so you can leave it on all the time. Thus, the automatic “shoot without lens” adjustment is actually redundant.

Of more use is the button on the side of the adapter which opens up the lens menu on the screen or in the viewfinder. This enables you to make on-the-fly adjustments. The only other way of accessing this screen is via the main menu, which is something of a distraction.

I was disappointed to find that this is not one of the customisable options in the new Quick menu set-up feature released in the recent firmware update. If it were, it would render the “electronic communication” pretty irrelevant, ten little brass contacts and all.

So, while the Fuji adapter is superbly made and very desirable, it does cost a whole £100 more than a perfectly acceptable and probably equally well-built alternative from Novoflex. The only real disadvantage to the dumb adapter is that you have to delve into the menu to adjust the lens-setting screen.

What does impress, however, is Fuji’s dedication to improving the experience of using manual lenses on X-Series cameras. The lens menu, even if it offered no adjustments, is a useful feature in providing metadata information. Other manufacturers such as Sony do not even make this provision when it would be so easy to implement. And Fuji goes further. While I suspect the lens adjustment capabilities will be neglected by most users, purists will take delight in tweaking the settings for their individual optics. All of this, not forgetting the emphasis placed on focus aids and the twin-frame view, shows that Fuji understands its customers’ needs.

Conclusion

The X-T1, with its split-image simulated rangefinder, makes the use of manual lenses much easier and more attractive than ever before. Together with the side-by-side viewfinder image, it renders the X-T1 more suitable for manual focus than other interchangeble-lens camera in the X-series (and, arguably, better than any other camera on the market). If you already own Leica or Voigtländer glass and an X-T1, then rush out and buy an adapter and get shooting. You won’t regret it.

My colleague Bill Palmer has previously written about his experiences with manual lenses on the X-Pro 1. See his views and sample pictures here.

Damn you Mike! You’ve got me fancying a graphite silver XT1 now! It’s your fault that I started on this odyssey. Having read your XE1 article, I bought a Leica lens and xe1 body for myself. Wasn’t happy with the corner performance, so sold the Fuji and bought a Sony nex6 instead. Then it was a M3, now it’s the m8.2 – all in the space of 12 months! At least I’m back down to one body and 2 lenses!

Oooer, guilty as charged, m’Lud. Never mind the corners, though, feel the pleasure of GAS. I am sorry if I have forced you to spend money. Happy holidays!