Somewhere around the late 1970s I started taking an interest in the nascent world of personal computers and wondering how they could be used to make my public relations company more efficient. There wasn’t much choice, as I remember, and it was a toss up between the Commodore PET and the Radio Shack TRS-80. I chose the wrong one.

I put down my money for one of the first TRS-80s to arrive in Britain and I drove all the way to Walsall, in the Midlands, to collect it from the Tandy HQ. I chose it because it looked the more professional of the two options: The Commodore PET, which turned out to be a much more useful device, resembled an overgrown calculator with coloured keys and a curious trapezoid monitor stuck on top. I was seduced by the false allure of the Jezebel from Walsall.

You need software

The TRS-80 taught me a lot about computing. Mainly, it told me that a computer is no use without software, which it signally lacked. I had fondly imagined I could make this thing write letters, run the accounts system and, generally, facilitate walking on water. But without software it was an impressive-looking but useless ornament. I suspect that, at the time, I had a very hazy idea of what software was all about.

It is incredible to realise that at the beginning of the 1980s, Radio Shack, recently demised, was a leading light in personal computers. Yet it was soon swept away by machines running the CP/M operating system. In my office we progressed from the Superbrain, which actually did do all the things I expected, to the rather spiffing range of Apricots, a long-defunct range of British models. All this happened in the course of two or three years until IBM took over the world with its PC, running a version of Bill Gates’s MS-DOS.

Between 1978 and 1985 the effect on office life of the personal computer was truly revolutionary. I watched the transition from manual systems that had changed little in a century to something resembling modern techniques, all within the space of a year or two. It was a shock for old office hands. Even then, for years, the PC was seen as a replacement for the typewriter and was operated by a secretary. Now the personal secretary has all but disappeared and there is a computer on every desk.

Enter the pee

I’ve previously written about working in the office of the historic 1960s, the preserve of the manual typewriter and duplicating machine, a time when we calculated in pounds, shillings and pence. And I brought this more up to date with office life in the 1970s, covering the dominance of the electric typewriter, the telex machine and rudimentary mechanical automation.

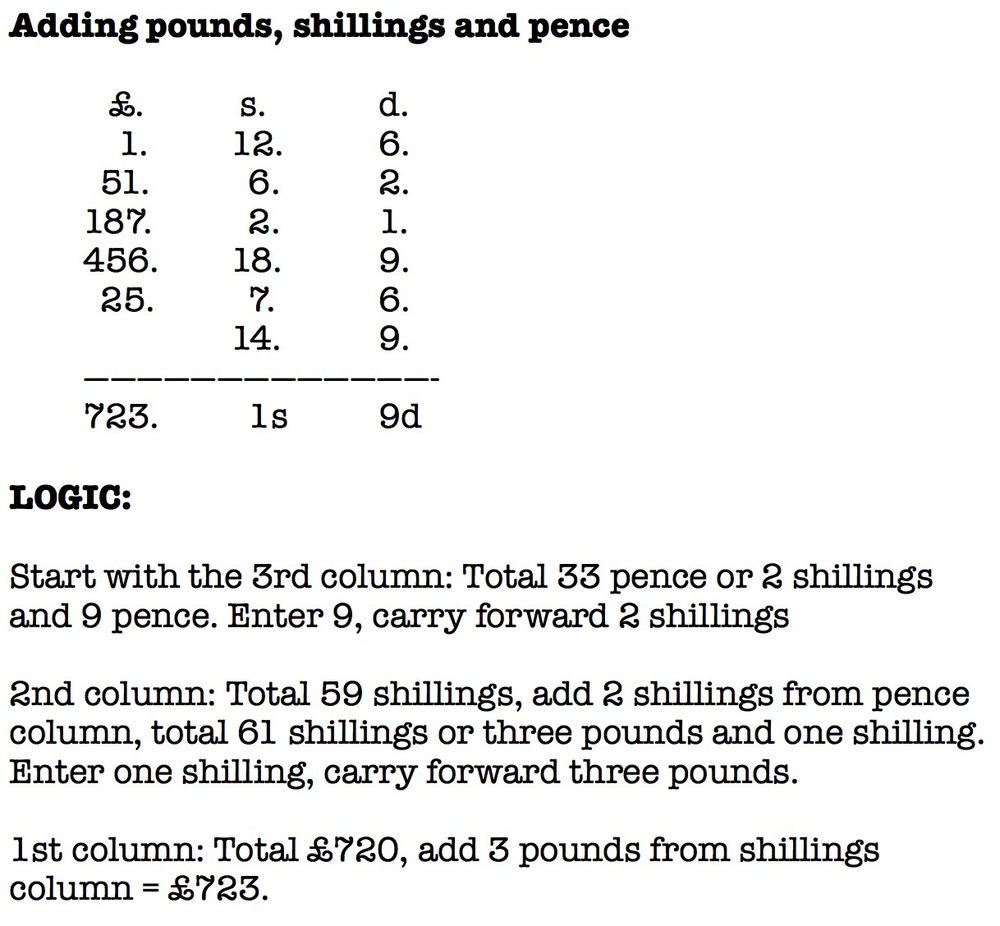

Before 1971 British offices had to wrestle with the complexities of a duodecimal currency based on 240 pence to the pound, 12 pence to the shilling, 20 shillings to the pound. This held back computerisation of accounting systems. Decimalisation came just in the nick of time. Note the old abbreviation for penny, d, which comes from the Roman denarius and which was replaced by the inelegant and immodest pee (which I still refuse to use, preferring the full word penny or pence as was always the case with the d). This is how it all worked:

In this system, which dated back over a thousand years, the penny had started as a small silver coin and a pound was a pound’s weight of pennies (all 240 of them). By the 1960s we had six coins: Penny, two pence (tuppence), six pence, shilling, two shillings (florin) and two shillings and sixpence (half crown). Notes came in denominations of ten shillings, one pound and five pounds. Ten, twenty and fifty pound notes were a later innovation as inflation geared up under a succession of inept governments.

Prior to the 1970s two other coins had already been pensioned off: The farthing (one quarter of a penny) and the twelve-sided three-pence, known universally as the thruppenny bit. Interestingly, this 12-sided design is to be reprised in 2017 with the introduction of the new one pound coin. It will be worth about as much as the old thruppenny bit, so we come full circle

See this article in Mashable which reproduces the 1981 Radio Shack TRS-80 brochure

Wonderful piece! Back then I was working in a small accountancy firm in the City, as one of the new boys I got the crap jobs, including I remember auditing the accounts of the pension fund of a Scottish shipyard. They had been neglected for a number of years, so even in the mid-70’s I was forced to work in pounds, shillings and pence……….it made the days seem even longer…………….now I sit in my office with three screens, I believe it is called progress.

Progress indeed. In my teens I worked for the then National Provincial Bank. In our small branch we had no means of calculation other than our heads, not even a mechanical adding machine. I became adept at adding up columns of figures up to 18 inches long. This sort of mental arithmetic never leaves you and I can still cast a long column with accuracy after all these years. Nowadays people use a calculator to add 2 to 3 with the result that their mental-arithmetic "legs" have turned into flippers, never to return.