For years the various D-Lux models have been the darlings of Leica aficionados. Light, fast and long-reaching, these little cameras have continued to impress with their versatility and their image quality. The latest D-Lux (Typ 109) continues this tradition but differs in a radical way. The new body, just a shade bulkier than the outgoing D-Lux 6, houses a 4/3 sensor that is almost five times as big as the 1/1.7 chip in the earlier camera. Yet the new camera has sufficient reference points to make the D-Lux 6 shooter feel completely at home.

Sensor

The nominally 16.8MP CMOS sensor comes with a proviso. There are four aspect ratios to choose from on this camera and all result in a cropped image because the lens, even at 4:3, does not fully cover the sensor. Maximum effective pixels of 12.5 come with the 4:3 format which is the one I prefer to use. Other ratios range from 12MP at 3:2 to 10MP at 1:1. It would perhaps be kinder to describe this as a 13MP sensor.

In terms of lens compatibility, the 4/3 sensor is cropped by about 10% relation to MFT sensors on other cameras. The ratio is 2.21 as opposed the straight 2 of MFT. This results in an unusual lens focal length range of 10.9 to 34mm which translates into a 35mm equivalent range of 24-75mm. On a normal MFT sensor the D-Lux lens would be a wider but shorter 22-68mm.

Design

The D-Lux looks like a typical Leica, not a rebadged Panasonic. Leica do have a big say in the development of joint cameras and the design influence is obvious. This one looks every inch a Leica.

While the Panasonic LX100 might be a little more easy to handle, with its small built-in grip, the D-Lux exudes class and is much prettier in my opinion. It is more expensive than the LX but you get a better looking camera with typical Leica styling features as well as a more substantial warranty and after-sales service. On past evidence it will hold its value better and will still be desirable in Leica circles long after the cheaper Panasonic has been forgotten.

As with the M, X and Q Leicas, major settings can be seen at a glance. And the control layout is simple and accessible. This is a real photographer’s camera.

On the top plate are the shutter-speed dial (topping at 1/4000s but with an electronic shutter taking this to 1/16000s) and the exposure compensation dial to the right. This is actually a better layout than that of the X-series cameras which forego a lens-based aperture ring in favour of a dial in the space where we now expect to find exposure compensation. Only with the new Q has Leica moved to a lens-mounted aperture ring similar to that found on traditional manual M-mount lenses.

The on/off switch is concentric with the shutter-speed dial and rather fiddly to get to as a consequence. A shutter-button combo (as with the M, Q and X cameras) is preferable. But this prime space on the D-Lux is occupied by the zoom lever. As such, it is an acceptable trade-off because the zoom lever is in constant use.

The movie button, which frequently gets in my way on other cameras, is sensibly placed out of the way above the impressive 921K dot screen, just below the shutter dial. Whether keen videographers will appreciate this odd placing is another matter. On the X, which I reviewed last month, the movie button is on the top plate, constantly lurking under a wayward index finder. With the D-Lux, in the unlikely event that you are prone to pressing the movie button by mistake, you can disable it in the menu. The Leica X and Q do not even allow this level of comfort. Also on the top panel, above the screen, are a wifi button and AF/AE lock toggle.

Unlike the M, X and Q, there are no controls to the left of the screen—just four buttons and the direction pad to the right. The buttons are for the excellent customisable quick menu, playback, delete/back and display (which toggles through different degrees of screen clutter). The direction pad buttons cover ISO, white balance, focus mode and drive/time settings with menu/set in the centre. The D-pad is not over-sensitive and I was not plagued by unexpected results when pressing the ball of my right thumb against the back of the camera.

Finally, there is a rubberised pad with a slight raised edge to act as a thumb grip. In use it is not so much grip, more tactile reminder of where to place the thumb to keep it out of harm’s way.

On the top plate, alongside the shutter release, speed dial and exposure compensation dial, are two further controls: F brings up a menu of special effects and A overrides settings to select full intelligent auto mode if required. This button is also inconveniently close to the on/off switch and it is easily pressed by mistake, thus selecting full auto which is not the first choice for experienced photographers. The remedy is to modify the action of the A button in the menu to Press and Hold.

Overall, apart from these minor quibbles, the control layout of the D-Lux is very well designed and implemented. I felt at home almost immediately and there are no serious negative aspects as far as I can determine.

Although around 100g heavier than the outgoing D-Lux 6, the D-Lux is still a small and handleable camera. It weighs in at 405g, ready for the road, and dimensions of 118x66x55mm. With its built-in viewfinder it is indeed a compact package for what it offers and for the size of the sensor.

Lens

The 24-75mm lens of the D-Lux, comprises 11 elements in 8 groups with 5 aspherical surfaces, is slightly shorter at the long end—75mm compared with the 90mm of its predecessor. It is also a tad slower at f/1.7 to 2.8 compared with the f/1.4-2.3 of the D-Lux 6. This is a necessary compromise in view of the larger sensor. To have created a similarly fast lens with an equally narrow aperture range for the larger sensor would have resulted in a much bulkier lens profile.

Leica will also have taken into account the fact that the bigger sensor enables the D-Lux, even with its slower aperture range, to gather more light than the old lens. The lack of the longer 90mm optical zoom is no handicap since a cropped image of the 75mm frame is just as good if not better. So D-Lux 6 owners should not get too hung up on the difference in lens specifications.

The new Vario-Summilux on the D-Lux is a gem. The traditional Leica aperture ring is there, to the front of the lens. Unlike on some non-Leica lenses (such as Fujinons), it moves from wide on the left to narrow on the right, something we are all so accustomed to. The smooth aperture ring has two raised and serrated sections that make it easy to adjust with the single finger. The A setting next to the widest aperture engages auto aperture, thus putting the camera in shutter priority. The shutter dial has an A setting to allow shutter priority. Setting both to A puts the camera in program mode.

The lens features a well-damped focus ring but without pretensions to a fixed short throw as seen on Leica X and Q. It twiddles round and round for a very good reason: It is a soft feature and can be adapted for other uses, including operation of the zoom if working in auto-focus, or as an exposure shift function. While the benefits of a customisable ring are clear, the lack of a restricted range of travel makes manual focus less intuitive than, for instance, with the class-leading design of the new Q Summilux. This paragon perfectly simulates a manual lens.

Previous D-Lux practice is followed with the aspect-ratio control on the top of the lens nearest to the camera body. Here you have direct, physical switching to 3:2, 16:9, 1:1 and 4:3 without delving into menus. I have never found this function particularly useful but I know several D-Lux owners who love it and regard it as one of the most impressive aspects of the camera.

On the left-hand side of the lens is the now-familiar focus mode switch (MF, Macro, AF) which is another example of direct physical access for such an important feature. Sensibly, the main choices of MF and AF are at either end of the slider switch so changeover can be accomplished by feel.

The resting lens, with the camera switched off, is 28mm long. Switched on, it extends to 62mm at wide angle and 81mm at 75mm, a considerable beak for for such a small bird.

Unlike the earlier D-Lux models, this lens has a thread and a 43mm UV filter can be fitted to protect the lens. With a filter mounted, I don’t see any need to use the lens cap; it can stay in the camera box where it won’t be lost.

Leica do offer an accessory automatic lens cap which I know many users love. I find it a bit ugly and prefer to stick with the filter.

There is no supplied lens hood and I didn’t find one necessary even in bright June sunlight. I always try to get away without a lens hood if I can.

The D-Lux has the big advantage of an electronic shutter to extend the range from 1/4000s to 1/16000s allowing use of a fast aperture even in bright conditions. Again, this is by choice. In the menu you can select manual, electronic or auto (where auto comes in to play if 1/4000s is too slow). I found that with even the brightest subjects I could shoot easily at f/2.4, if not f/1.7, without hitting 16000s. The mechanical shutter up to 1/4000s is very quiet and higher speeds are silent.

Autofocus

Autofocus on the D-Lux is faster than on the previous model. It isn’t quiet as speedy as on the new Q but is definitely above average. It works quickly and accurately in good lighting conditions and, as with the Q, suffers less performance degradation in lower light than expected.

There are the usual AF modes to choose from, comprising face detection, tracking, 49-area, single area (which is flexible and scalable), custom multi and spot. This should keep anyone happy although, as usual, I prefer to work mainly in spot, fixing focus and then recomposing. Recently I have developed a liking for face detection and the D-Lux system is quick and accurate in this mode.

Macro mode works down to 3cm compared with the normal range of 50cm to infinity.

Manual focus

This is a very satisfying camera to use in manual focus mode. For starters, the focus ring is smooth and fast although, as previously explained, it lacks the clear stops at near and far seen on X and Q models.

There is the option to set a 10x magnified focus area which appears automatically when the ring is nudged. Another trick, which I haven’t encountered before, is the ability to use monochrome preview without having to set jpegs also to black and white. Focus peaking is very effective against a grey-tone background rather than against the usual colour which can sometimes lead to confusion. I set peaking to medium, yellow and was surprised how easy it is to get accurate focus on a monochrome background.

When in manual focus mode a focus scale appears at the bottom of the image (according to view setting) but it has very imprecise markings and is of limited use.

When using manual focus it isn’t essential to use peaking of course. Judging by eye is easy. As with most digital cameras, there is a pronounced shimmer in the image when sharp focus is achieved.

Viewfinder

Previous D-Luxes had no built-in electronic viewfinder. On the D-Lux 6 an external finder could be fitted in the hotshoe but at the expense of camera size.

The new camera breaks the mould decisively. It has a built-in viewfinder which is bright and clear, with little lag except a small amount of smearing when panning. With 2.76M dots the resolution is remarkably good, well above average, although the image itself is smaller than that found on larger cameras such as the Q, Fuji X-T1 and Sony A7.

The built-in finder is a big advantage and transforms the camera, both in terms of practicality and in reduced overall bulk. The old D-Lux 6, with external finder, was much more difficult to stow in a bag.

The viewfinder has a substantial diopter adjustment to the right of the rubber eye-cup that is easy to adjust and yet refreshingly well away from prying fingers. Once set it stays set, unlike on the Q, and I had no need to get out my roll of black tape.

Transition between screen and viewfinder is also well sorted. The EVF button to the right of the finder selects the three modes—viewfinder only, screen only or eye-sensitive switching. This is the perfect implementation. Sony and Leica please note: The A7 and the Q lack such an easy way of switching. Once set to viewfinder only (which many photographers prefer) both cameras make it necessary to go back into the menu via the viewfinder in order to switch back. So full marks to the D-Lux for the best-possible implementation of view switching.

Above: Leica porn in the form of a heavily modified M7 all the way from Hong Kong and the Leica specialist dealer of Fotopia. Taken at 70mm, 1/500s @ f/4. The bottom shot is a crop from the top image

Menus

The menu system is similar to that of the D-Lux 6 and is easy to navigate, though not as simple as the layout found on European-made M, X and Q ranges. I appreciated the optional scrolling help line at the top of the menu screen which explains the functions while browsing. The scrolling is too slow for my taste and eventually I switched it off. It is undoubtedly useful for the initial learning period. Overall, I found the menu system easy to use and less confusing than those on other cameras, including the Sony A7.

Flash

Unlike previous models, the new D-Lux loses a flash in favour of the viewfinder. This is an welcome decision and is something that should be followed in all Leica digitals (X and X Vario in particular: the Q has already caught up with the modern age). Instead, the box contains a small accessory flash to cover up to 8m at the wide end of the lens and 5.2m at the long end. Since I almost never use flash, the little unit stayed in the box.

Connectivity, video

The D-Lux offers wifi conceivability to the Leica shuttle application but, again, I did not have the opportunity try it out. Nor did I get to grips with video which is perhaps as well since I am signally unqualified to pronounce. According to the spec sheet, the D-Lux offers up to 4K compatibility and I believe it is the smallest camera on the market with this ability.

Zoom, essence of the D-Lux

The ability to alter focal lengths is the essence of the D-Lux and is the reason you would choose it over a similar-size fixed-lens compact. Coming straight from the X and the Q, I espoused the zoom as an almost illicit pleasure. I spend a lot of time convincing myself that fixed-lens cameras, including the M, are the best creative tools; that zooming is best done by the feet and that owners of zoom lenses spend more time zooming than composing. There’s a smidgeon of truth in all such prejudices but it is undeniably liberating to use the D-Lux with its smooth ability to change focal lengths.

My favourite feature of this lens, as with all the D-Lux versions, is the optional stepped zoom. You can set the lens to jump in fixed increments between the “standard” focal lengths —24, 28, 35, 50, 70 and 75mm. I find it much easier and more logical to snap step-by-step through the focal lengths rather than fiddling with an infinitely variable zoom. Liken it, if you will, to a good manual gearbox in comparison with a continuously variable transmission. You know precisely where you are at any stage of the game. The W/T lever mounted on the top plate in front of the shutter release is very convenient. When step-zoom is activated a quick flick of the lever to right or left moves to the next focal length. Without the step-zoom feature it operates as a smooth variable zoom.

Above: Cycling through the steps from 24mm to 75mm

What’s more, you can tell the camera to resume the previously used zoom setting. So, for instance, if you determine to have a 50mm day you can simply select 50mm and it will stick, even when the camera is turned off. This is manna for photographers who have grown up with fixed-length prime lenses. It is the digital equivalent of having a bagful of lenses at your disposal. It works, too, with longer focal lengths right up to 300mm when using the digital zoom.

This ability to hard-wire a focal length is incredibly useful. It would be even handier if the lens barrel were marked with the zoom steps, to provide a visual status indication, as I have seen on other manufacturers’ lenses. This should be possible because the barrel extends logically in clearly defined steps up to the maximum of 75mm (the digital zooms are simply crops so the lens stays at its 75mm position when moving to 150mm or 300mm).

Let’s not forget, too, that the stepped zoom is a good educational tool for photographers who have not grown up on prime lenses and want to familiarise themselves with what can be achieved at specific focal lengths.

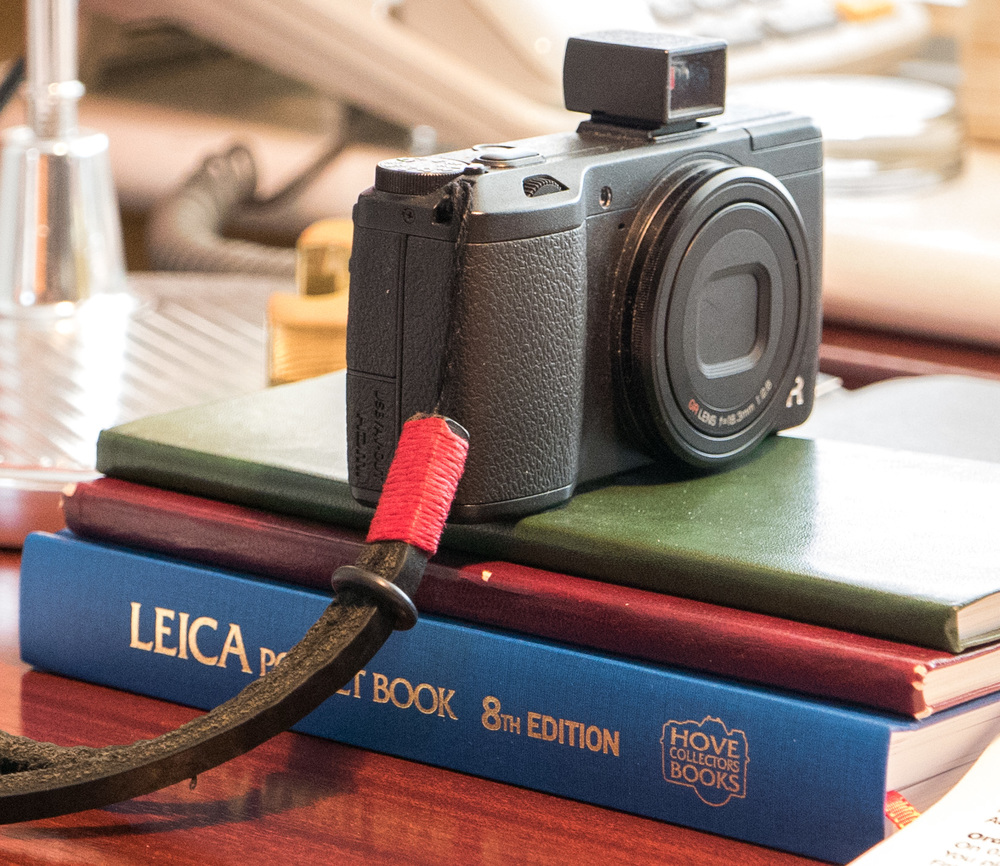

Now for the digital zoom functions. Most of us never use digital zoom, condemning it as no better than post-process cropping. Which is true. But there are sometimes advantages in composition and framing when using a digitally cropped view, particularly when combined with a larger sensor. While digital zoom and cropping was of little practical use on the previous D-Lux 6, it is now very usable because of this camera’s large 4/3 chip. It makes more sense the bigger the sensor, as demonstrated with the 35/47mm crop function on the Ricoh GR or, even better, the 35/50mm crops on the full-frame Leica Q.

Above: The wider image is taken at 75mm, the second close-up is a 1/4 crop of the 75mm frame to achieve 300mm digital zoom setting. It is just about acceptable.

The D-Lux offers two ways of using digital zoom. The standard setting, if selected, takes the lens to a 35mm equivalent of 300mm (based on a x4 crop of the longest optical setting of 75mm). Results at 300mm are just about acceptable and should be reserved for special occasions; you won’t win any prizes with the pictures, unless the decisive moment outweighs the image quality.

Much more usable and logical is the i-Zoom feature. This offers magnification up to twice the 75mm frame—in steps from 90, through 135 to 150mm. The degradation at this crop is kept to a minimum by dint of some electronic wizardry and I was impressed with results. The i-Zoom feature is highly usable and I was happy to leave it selected and available most of the time. As with the Leica Q, the zoom works on JPEGs only and you have the opportunity to recover a full DNG image in post-processing (although, as previously noted, the aspect ratio applies also to RAW files and cannot be undone in PP).

Armed with the step function and the i-Zoom range of 24-150mm, the D-Lux is one of the most versatile and competent compact zoom cameras I have ever used.

Handling

In return for the gorgeous retro looks of the D-Lux you forego the convenience of the rubberised grip as found on its Panasonic alter ego. I can’t make up my mind whether or not this is a worthwhile trade, but I am sure that the D-Lux looks better for it. Leica does offer a screw-on grip which improves handling (I didn’t have the chance to try but I have used and appreciated similar grips on other Leicas, including the old D-Lux 6) at the expense of slightly increased height. Often, though, I am happy to lose a front grip and make do with a thumb grip.

That apart, the D-Lux is something of a triumph in the handling stakes, especially for anyone who appreciates manual controls. There is something just right about it and it has the ability to inspire the typical Leica user. The D-Lux contrasts with its near-competitor, the Sony RX100 Mk III which has a fiddly and fairly average pop-up EVF and an over reliance on soft controls. The D-Lux is bigger than the Sony, and has a much bigger sensor, and I count this as an advantage in handling terms. In some ways it reminds me of a smaller, much more modern version of the old Digilux 2.

In use

While the D-Lux is not a pocket camera (except, perhaps, when wearing a winter coat) it is very compact for what it is and makes an excellent travel companion. It is small in comparison with, for instance, an equivalent MFT system camera from Panasonic or Olympus and it offers a much brighter lens than you would see in an MFT system kit.

I spent a week with the camera, carrying it with me to the Bièvres Camera Fair near Paris, and I thoroughly enjoyed its versatility and sheer competence. It is a joy to use and feels compact and yet suitably chunky in the hand. In fact, it feels just like the old D-Lux 6 but, crucially, you know you have the benefit of the near fivefold increase in sensor size should you manage to grab that once-in-a-lifetime shot.

The lens is very sharp in the centre throughout the range although there is evidence of some softening at the edges. I imagine there is considerable software correction taking place but I found the results consistently pleasing. When all is said and done, it is the final impression that counts and I was very happy with the output.

The D-Lux boasts a fast lens with optical image stabilisation and a good ISO performance, certainly up to 3200 but ranging to 25000 in push mode. I would be happy to set 1600 as a top sensitivity compatible with acceptable results. But, if push comes to shove, even 12500 is available.

Image quality is outstanding, particularly in comparison with the outgoing model. Pixels count, however, and the D-Lux sensor is still a slightly hobbled four-thirds and cannot compare with a good APS-C sensor such as that in the Ricoh GR. That camera, despite the handicap of a fixed lens, offers greater resolution.

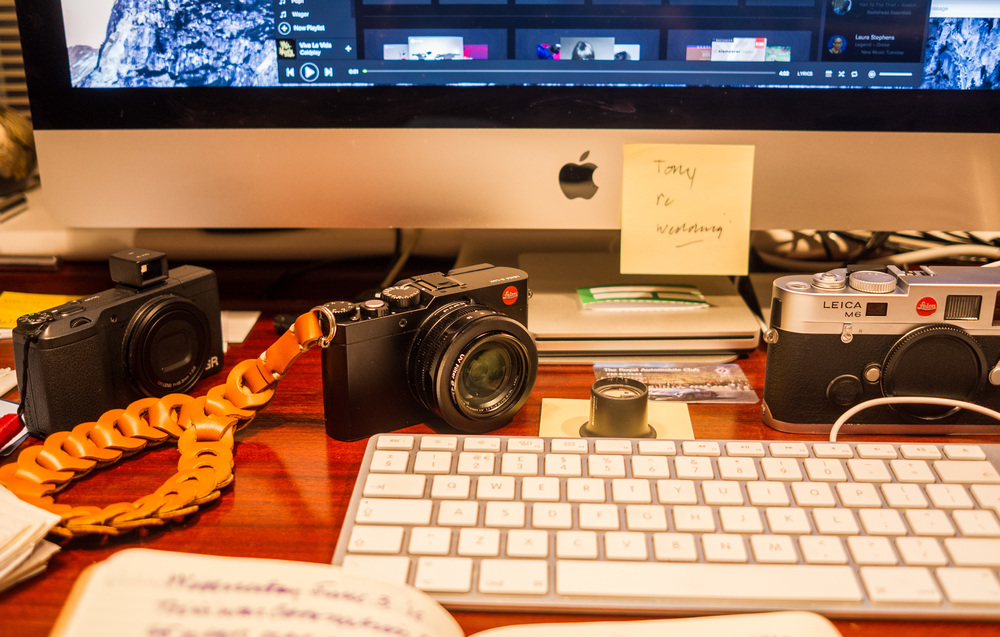

Finally, a word on battery life. Leica claims around 300 shots per charge and, as with the recent experience of the Q, this seems on the optimistic side. I found myself at the Bièvres camera fair with just one battery for the review camera and it was nearly dead midway through the afternoon. Fortunately I had the Ricoh GR in my pocket as a backup.

Relatively short battery life is endemic these days, a result of striving for small body size and greater performance. It is the same dilemma faced by Apple with the iPhone and Watch. You should certainly plan to buy at least one spare battery if you opt for the D-Lux. Bear in mind, however, that my review camera was new when I collected it from Leica Mayfair. Batteries usually improve their capacity after five or six complete cycles.

Second opinion

Aware that reader David Askham has owned a D-Lux for several months (and I had barely a week to form an opinion), I asked him to add a few words on his experiences:

For the past three months the D-Lux has been a regular companion for my full-frame M or APS-C X Vario. It is my notebook camera with the potential for more demanding photography. Its larger sensor (in relation to the old D-Lux 6 at least), excellent viewfinder and fast zoom lens make it a very versatile instrument, fully capable of being a competent travel or photo-reportage camera in its own right.

There are a few minor irritations for a user more accustomed to the beautiful simplicity of Leica-designed menus and camera ergonomics. For example, there are 27 pages of on-screen menus augmented by several user-customisable function buttons scattered around the camera body. For the most part you can ignore the options unlikely to be used. However it is possible, inadvertently, to actuate an unwanted function and then waste time trying to rediscover how to restore your way of working. In summary, though, the D-Lux is a compact, discreet, high-performance camera with excellent built quality and stunning optics.

Initially I found the review function to be frustrating because by default it forces you to zoom out and then re-zoom every time the next picture is selected. I like to retain the magnification as I move swiftly from one frame to the next. This is particularly the case when comparing two or three adjacent images. How to do it? Magnify one image then rotate the control dial outer ring one way or the other. This makes it easier to select the sharpest frame from a sequence of shots. I don’t think this is documented.

Finally, I do deplore PanaLeica’s failure to issue a Leica-style instructions book for this camera. It should be one of the benefits of paying the Leica premium price to have a proper Leica manual.

I would like to thank David for reading the draft of this article and suggesting amendments and additions.

Conclusion

This is a very attractive and desirable camera, a real cutie. It is one of the most effective travel cameras you can buy and is a another winner for Leica. In fact, in my opinion Leica now offers two superb non-M travel cameras in the D-Lux and the Q. I can see many well-heeled Leica fans opting for both in addition to their chosen M or Monochrom.

The D-Lux is perfectly capable and satisfying when you have to travel light. It offers all you need in flexibility and versatility with great image quality. Optionally, packing a Q or M adds full-frame goodness for those technically demanding shots.

Warranty, price

As with all Leicas in Britain, the D-Lux comes with Leica Passport, a one-year accidental damage insurance, plus a two-year warranty. In addition you get access to a copy of Lightroom and, of course, benefit from the long-term added value of the Leica brand. The camera has a recommended price of £825.

More Leica tests by Macfilos

Gallery

Above: Cycling through focal lengths, 24mm, 75mm and 300mm (digital zoom)

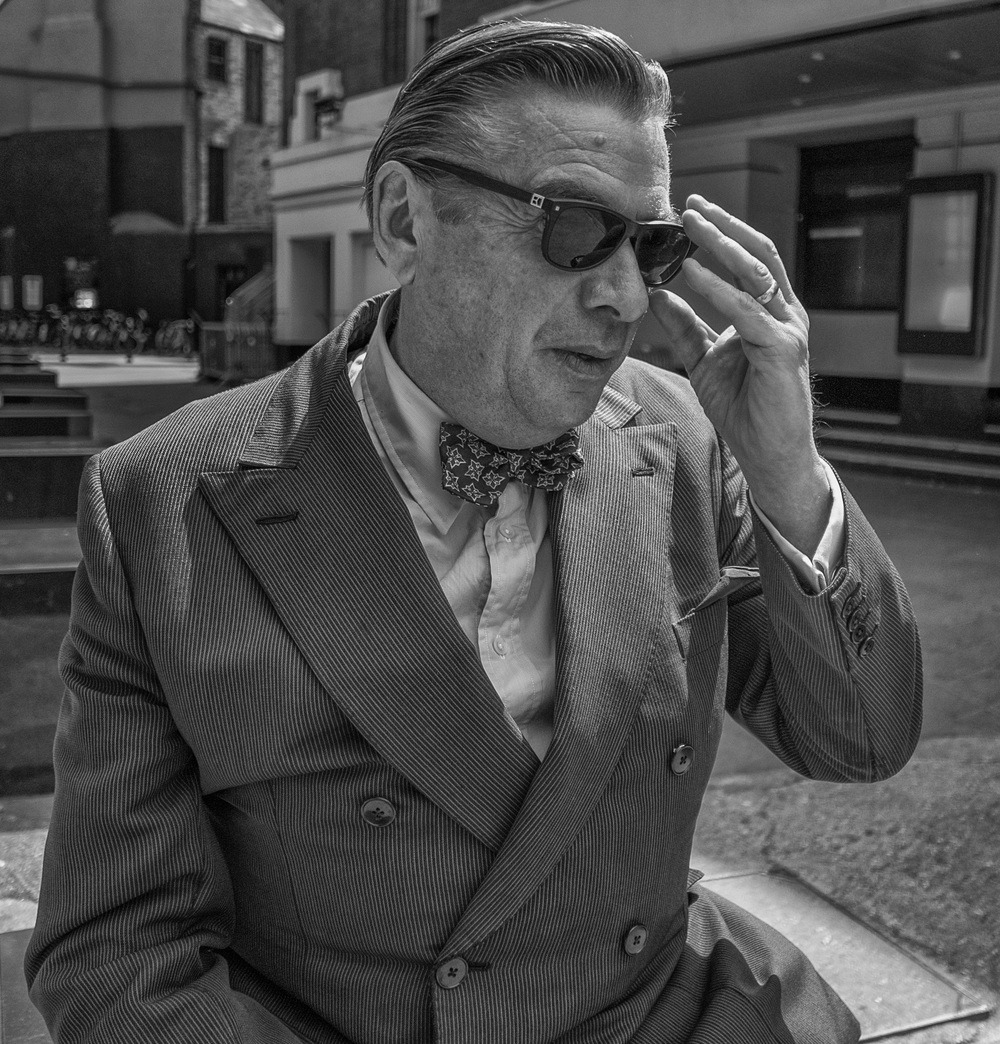

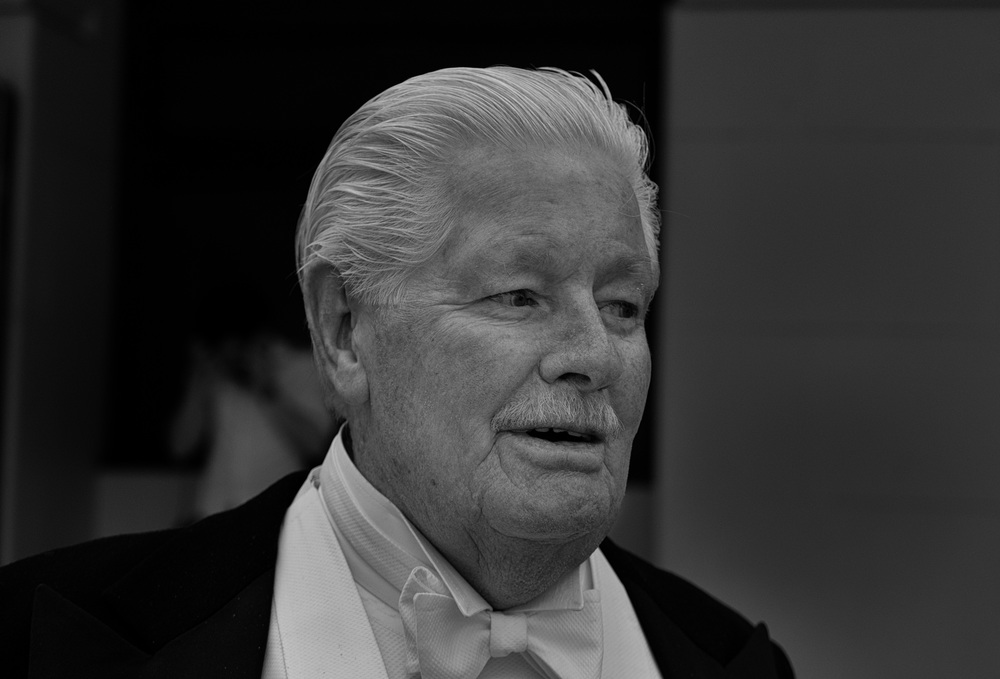

The following black and white images were processed in Silver Efex Pro