‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’—a philosophy I usually live my life by. I’ve never been prepared to make an exception when it comes to developing film, either. Over the last few years, I’ve had great success following manufacturers’ instructions; that’s taken me through developing black and white, C41 process and E6 process in the comfort of my bathroom, without any real issues. However, it struck me that there is one particular aspect of film photography that has made me such a die-hard advocate: Variety.

Overlooking interchangeable lenses, it is possible to shoot every manner of photograph with a single camera body; be it a Nikon SLR or a classic, all-mechanical Leica. Every film emulsion has a unique look: A unique rendering of shadow, highlight and midtone detail, a unique grain, and a unique way in which it reacts to light.

Infinite variables

You’d think that trying a hundred different types of film would satisfy this niggling I-wonder-how-this-looks question that persists in my mind’s eye. However, there’s the almost infinite array of variables associated with how you process the film that can also drastically alter the resulting string of photographs.

Since my start in black and white, and having experimented with one or two developers, I had settled on Ilford’s ID-11. Akin to Kodak’s famous D-76 in many ways, this developer has never once let me down. I’ve developed everything from Pan-F through to Delta 3200—largely with a very forgiving tolerance to shaky exposure, and a good balance between sharpness and grain that’s not too visually obtrusive, while still characterful.

Rodinal to the rescue

Years ago, I bought a bottle of Rodinal; a developer famous for both its sharpness and its boulder-like grain. However, many photographers have reported using Rodinal in unconventional ways, producing images with outstanding midtones, great sharpness, and perfectly tolerable, aesthetic grain.

Unlike many other developers, Rodinal is often used in very high dilutions; 1:100 is a staple in many recipes, for example. These higher dilutions are often associated with higher acutance (sharpness) and finer grain in the resulting negative, and can lend well to stand development. This is a technique that dates back to the late 1800s, whereby the film is left to ‘sit’ in a tank full of developer for an unusually long period of time, with minimal agitation.

If this were to be done with higher concentrations, the risk of localised overdevelopment of your negatives could result in visible defects such as vertical streaking, where developer settles around the sprocket holes of the film, and flows downwards across the emulsion. This risk is supposedly eliminated by using higher dilutions.

Photographs that have been stand developed in Rodinal are characteristically sharp, with exceptional shadow and highlight detail, but are often low in contrast. Since I will be scanning the negatives and printing these in the darkroom, I prefer to have negatives rich in tonal information, that can be adjusted—either in Lightroom, or with appropriate filtration in the enlarger.

The Experiment

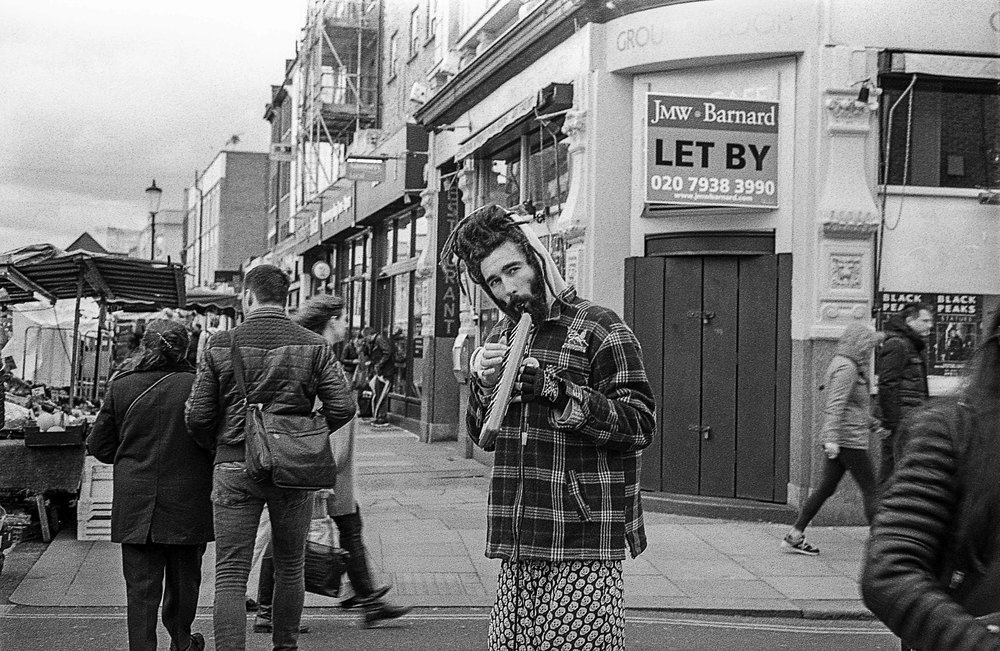

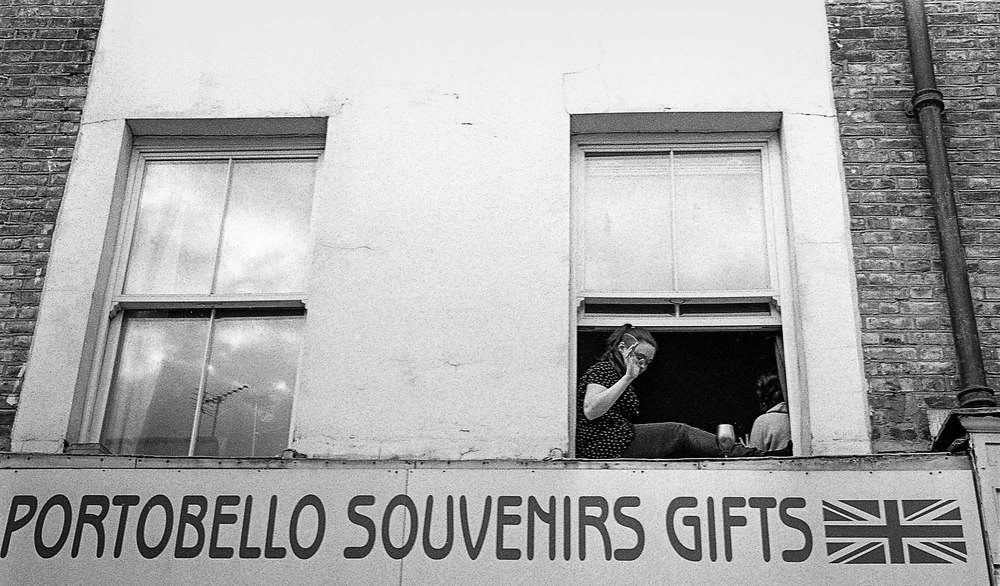

It was time for me to try this for myself. Following my photo walk with Mike Evans a couple of weeks ago on Portobello Road, I decided to return last Saturday, the day the market was in full tussle. I shot a roll of Tri-X and pulled the exposure index to 200, and thought that this roll might just be the perfect candidate for an experiment (despite my knowing that there were probably some decent photographs here that I might jeopardise).

Another interesting fact about stand development, is that times don’t require adjustment according to the film speed. Not really, at least. There are many reports of developing rolls shot at 200 and 800 in the same tank with sound results, for example.

While stand developing in high dilutions of Rodinal minimises the risk of streaking defects, the idea of my film sat still for too long unsettled me. I thus opted to try a semi-stand development technique, where I let the film sit for an hour and a quarter, gently agitating and tapping the tank every quarter hour; I’m paranoid about air bubbles settling over my images. And by gentle agitation, I mean swirling the tank slowly for about 10-15 seconds (not a full-on inversion).

My chosen dilution was 1:100. Also note that I decided to opt for a stainless steel developing tank, since the plastic reels in the newer Paterson systems allegedly influence micro-currents in flowing developer that can lead to unevenness and overdeveloped edges of the emerging photographs.

Further online reading revealed that a German photographer (whose translated observations are concretely preserved in scattered forum posts) discovered that colder developing temperatures could produce finer grain. He suggested using temperatures of 16-18ºC instead of the conventional 20ºC. Since I would not be regulating the temperature of my tank once development began, I decided to start out with 1:100 Rodinal cooled to 14ºC, assuming that this would slowly rise 3-4ºC across the hour.

The Photographs

Fully prepared for a disaster, I was astonished by the results. I was using 35mm film—and Tri-X at that, a film famous for its grain. I expected overbearing, coarse grain, and got the exact opposite. A beautiful, unobtrusive grain, exceptional capture of highlights and Rodinal’s characteristically beautiful rendering of midtone details.

Even in scenes with flat grey skies, the negatives had clearly retained everything from the subtlest wisps in the clouds, to the smallest objects beneath shady market stalls. Natural light fall-off and grain on skin tones were just perfect: This is one of my favourite properties of black and white film.

The photographs are scans using my flatbed. In my experience, these scans never elucidate the true intensity of a photograph’s sharpness, and over-pronounce grain when compared to a darkroom print. For anyone doubting traditional processes, you really have to see a well-made darkroom print for yourself to truly appreciate analogue photography at its finest. Nothing comes close. A bold statement, but one I’m prepared to make.

Right up my street

I cannot wait to try these techniques more, and experiment with stand development even further. The results so far have been right up my street; so much so that I can’t see myself returning to XTOL or ID-11 too soon. Once again, for anyone reading this who shoots film, I hope this will inspire you to experiment with your developer; or even to develop at home and give the local lab a break. It’s really nowhere near as difficult as it’s made out to be.

- Subscribe to Macfilos for free updates on articles as they are published. Read more here

- Want to make a comment on this article but having problems? Please

Editor’s note: This is the first contribution to Macfilos by Adam Lee and we look forward to further articles in the future, particularly on his passion for old Leicas and film photography. In addition to his interest in photography, Adam is a very talented guitarist. Take a look at this video.

[…] the subject! Classic Camera Revival – Episode 58 – Don’t Drink the Rodinal Pt. II Macfilos – Film Processing at the Dead of Night with a Bottle of Rodinal Martin Zimelka – Agfa […]

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2020/04/27/developer-review-blog-no-04-rodinal/

Good morning Adam… Excellent results!

I have had a go at stand development with Rodinal and I was surprised at the results too… My films were Rollei Retro 80 and Ilford FP4+…

I used as reference the piece by Colin Barey below on Japan Camera Hunter…

http://www.japancamerahunter.com/2013/10/black-white-film-development-lazy-people/

The biggest problem for me was that too many aspects were new to me so I didn’t persist and went back to using the recipes from Massive Dev for Rodinal and lately as I mentioned, XTOL stock.

Other new things to me, were Rollei film, Leica MR light meter, which I couldn’t work effectively due to my longsightedness (the settings markings are unreadable), and these were the only the seventh batch of films that I had developed.

The shock was that in my case, the Ilford had grain like the fabled boulders and the Rollei was much finer, but nearly all of the film was badly judged in terms of exposure.

Anyway, I have become much better at developing, and your encouraging piece here makes me want to try the Rodinal/stand method once again…

My bottle is now almost a year old and not been subjected to too much bright light, so should be OK?

How easy is it to use the wire spools compared with the plastic ones?

Hi Stephen!

Thanks so much for the kind words. Love the article from JCH – love the glow around the subjects in the images, too. I’m guessing I eliminated this by agitating more frequently, and employing this ‘semi-stand’ technique. I’d love to experiment with the full-on stand next time.

As for your results, I wouldn’t have thought the whole roll would have been poorly exposed. Stand development is supposed to even out exposure massively, and develop the negative by the ‘required’ amount, as it sort of allows the developer to exhaust. Hence, if the whole roll came out that way, it was probably an issue with development, I’d imagine. Temperature seems to be the grain-reducing secret. Go for cold next time, and try the more frequent agitation. It worked here! I did an hour and a quarter for pulled film. If I were shooting at box speed, I might try this for an hour, instead.

And your Rodinal should be just fine. It’s allegedly the toughest chemical in photography, with a shelf-life of decades (40 years rings a bell from what I had read). Pretty bullet-proof!

As for the steel reels versus plastic – I find them far more fuss-free. Definitely practice in the light first, but it’s all about curving the film in your hand, and cutting the leader off precisely as the best vertical you can manage. I’ve had issues with plastic reels catching my film when they get hot, or have any moisture. Not so with a steel reel. Also, the metal flanges are much thinner than the clunky plastic, so they only gently grip the film by the very edges of the sprocket holes. This is their advantage for stand, from what I read. When developing single rolls, I always reach for the steel tank. It’s just a more pleasant process, and you never have an issue with sticking or catching film. One of these days, I’d love to get a multi-reel steel tank system. If only they weren’t so hard to come by, and so pricey!

Adam 🙂

Dear Adam

Well done. These are lovely. This is one of those areas where practice and experimentation really help, but you only get one shot at developing each roll of film. I met a young guy yesterday at a photo fair who had got involved with the collodion wet plate process. He had a lovely French Full Plate camera on his stand which drew my attention. He and some others have been brave enough to set up a film developing and printing studio in Dublin recently. http://www.brunswickcollective.com . I told him that I would drop by some day.

I also like your music and, particularly, your B.B. King tribute. I am a fan of the older generation of jazz and blues musicians and he was the last of my favourites to have been still alive before he passed away last year. I was lucky to have seen him many times and other musical heroes such as Duke Ellington, Ray Charles and Muddy Waters before they passed on to ‘the great recording studio in the sky’.

William

Dear William,

That sounds very exciting. That’s one area I certainly haven’t delved into – anything large format. Film or otherwise! I figured I’d stop at medium format, since my scanner and enlarger go no further… Although I’m sure the enlarger could be modified a little to enlarge bigger negatives! His darkroom facility looks wonderful, and I’m sure his photography is, too.

And thank you so much regarding the video feedback – that’s actually my main thing: Music. I was heartbroken when B. B. passed away last year. You definitely have great taste and have surely witnessed magic to have seen such legends in concert. Ray Charles is one of my all-time favourites!

Adam 🙂