Mike sets the scene

In the previous article I explained how Adam Lee and I took three Leica film cameras, spanning 80 years, and tested them all against one another using the same humble bit of celluloid, the classic Ilford FP4.

The plan was to shoot in the same conditions (rain and drizzle as it happened), using exactly the same film and guide settings, and then process the film side by side to ensure consistency. Now we can move on to the results.

The cameras and lenses

Adam took along his minty 1957 M3 double stroke, newly CLA’d and purring like a pussycat, with his 1958 dual-range Summicron, one of the most sought-after classic lenses.

I added a brace of cameras to top and tail Adam’s mid-fifties classic. First came the 1935 black and nickel Leica III with a matching nickel 5cm f/2 Summar from 1936; then the quintessential modern film outfit, Leica’s newest (and still current) M7 with the finest 50mm lens Leica has ever produced—the needle-sharp Apo-Summicron ASPH. The three nicely provide exposure bracketing over 80 years and with differing levels of optical performance. Bear in mind, though, that the Apo-Summicron is a modern lens designed for digital. Personally, I wouldn’t spend that much because, as you see from the examples, a good Summicron of any age will keep you happy.

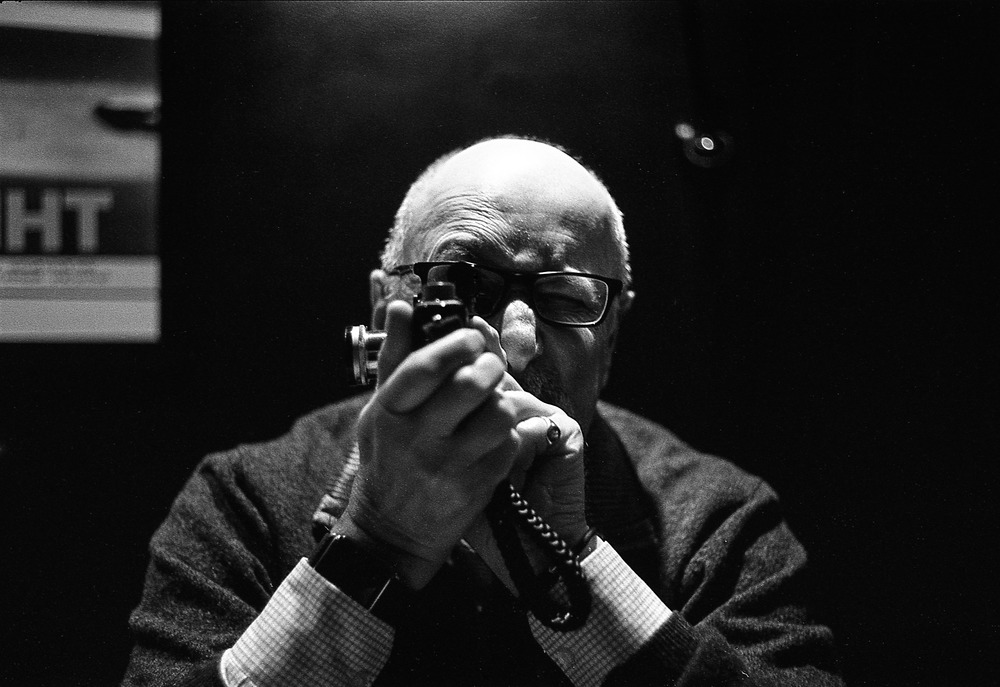

As a little fun on the side I added a classic bit of Leitz ingenuity, the “Wintu” Winkelsucher—corner or angle viewfinder. This fiendish device, which manages to replicate both rangefinder window and composing window on a stick, was expressly designed to see around corners. It was made for the screw-mount cameras and, to my eternal disappointment, cannot be used with a modern M.

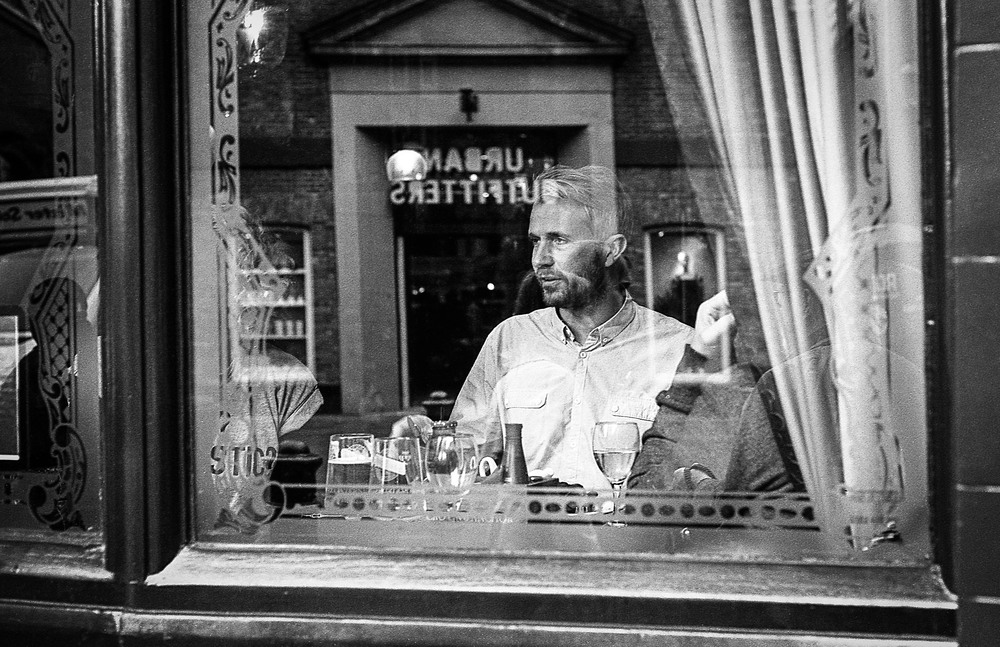

Sneaky shots round winkels

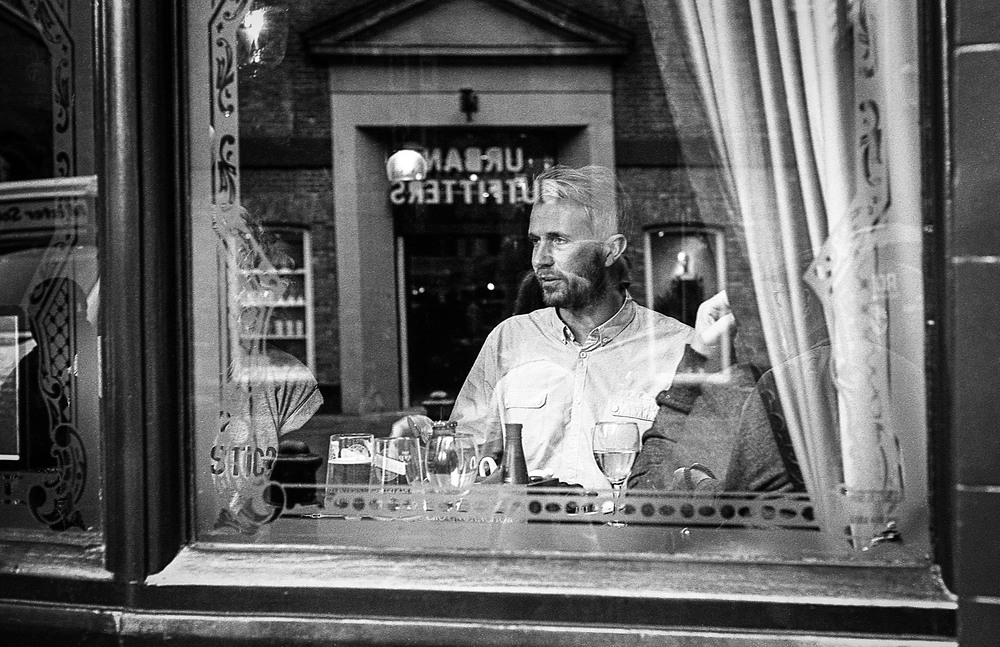

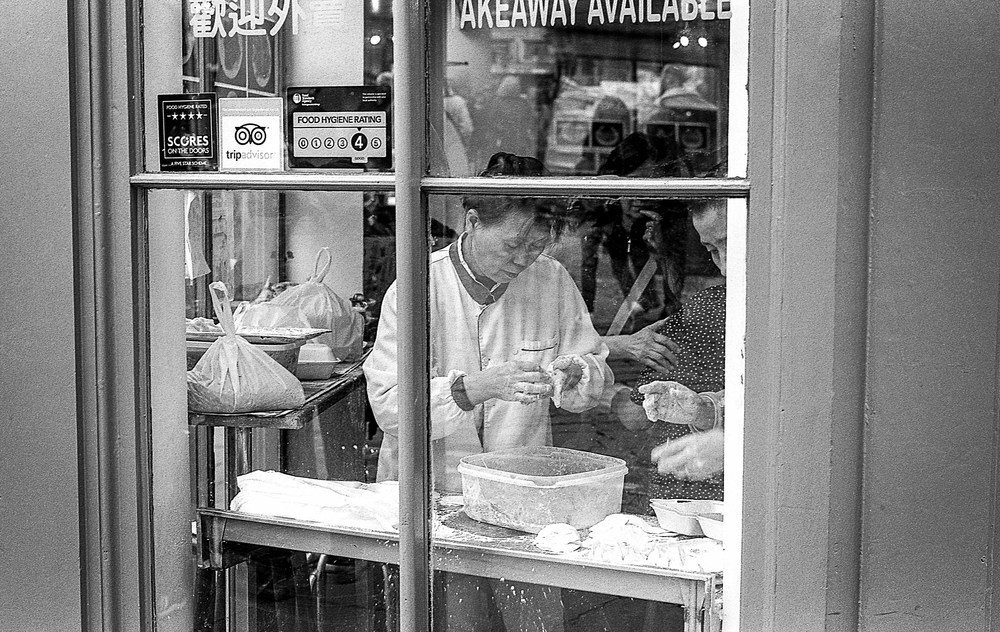

Endless fun is to be had with this device because, despite the obvious lens pointing in their direction, most people assume the photographer—who is sideways on—is taking his picture in an entirely different direction. As I said in the earlier article, this is one for Q and James Bond, not to mention the more intrepid private eye employed on divorce snooping.

These three cameras are significantly different in use. The pre-war screw-mount surprises with its twin finder windows—rangefinder on the left, viewfinder on the right. Unlike on later LTM cameras, where the two windows were brought close together, those on the III have a wider 20mm separation which I tend to prefer. It is easier to make the distinction between the two windows and less likely to lead to confusion.

The III also lacks the cocking lever which was introduced only in 1954 with the M3. All earlier cameras have a knob which has to be turned round to advance the film and cock the shutter. In its day, though, this was innovative in itself; it prevented a second shot being taken before the film had been advanced. This was a big sales advantage. On many earlier cameras there was an ever-present danger of double exposure.

This particular Leica III makes do with a fastest shutter speed of 1/500s which can lead to problems with a speedy lens such as the Summar. Fortunately, in last Saturday’s dull conditions we needn’t have worried on that score.

The Summar lens is truly an object of beauty in all its nickel glory. As William Fagan points out, nickel lenses in the early 1930s were the standard, cheap end of the market. Buyers would pay extra for chrome. Now, the situation is reversed and it is the nickel lenses that have rarity value and, hence, command higher prices.

Adam’s M3 is an early 1957 example with the double-stroke advance lever. It was made just before Leica changed over to the now-standard single-stroke. Initially, in 1954, there was a fear that the new rapid advance might break the film, so two stages were introduced. The M3 is a real classic and many owners prefer the double-stroke to the single-stroke. Adam is among them, as is James Fox-Davies whose luscious Japan Camera hunter customised camera was featured in a recent article.

The M3 is the classic street-shooter’s friend. It is again enjoying tremendous popularity, especially among young photographers such as Adam and, as a result, prices have risen considerably. To complement the M3, Adam brought along his 1958 dual-range 50mm f/2 Summicron, considered to be one of the best lenses ever made by Leica.

To round off the trio, I fielded Neil the M7, so called because it was manufactured as a customised a la carte model (complete with lizard skin) for a lucky guy by the name of Neil. I acquired it a couple of years ago and promptly named it Neil. After all, that’s what it says on the tin. Unfortunately, the engraved name on the back reduces the camera’s worth; bear that in mind if you are ordering an a la carte.

The M7, although this model dates from 2005, is still current and represents the ultimate distillation of Leica’s film manufacturing knowledge and expertise. Unlike the other two, which are purely mechanical beasts with no electronic metering, no batteries, the M7 has a touch of the new. It features both automatic exposure metering and an aperture priority mode, just like modern digital Ms. In fact, the M7 feels and acts very much like the digitals and, perhaps for this reason, it is often looked down upon. Purists prefer their MPs or M6s—or, even, the newly introduced M-A which is an unmetered modern replica of the early Ms.

If the M7 is modern, the lens I chose is hot off the workbench. The 50mm Apo-Summicron is said to be the finest fifty ever produced by Leica and I am not about to disagree. It is sharp beyond feasibility, deliciously contrasty and just about perfect. I don’t use that word lightly. So, in the M7 and 50 Apo we have what is probably the best combination of modern film photography you could hope for. I chose it simply for the contrast, both in price and optical excellence, to counter the olde equipment As I said earlier, however, it this lens is probably overkill. If you have one to hand all well and good. But otherwise choose something cheaper.

Taking these three cameras, we have a linear progression, both in terms of camera technology and optical development covering a no fewer than 80 years of what, in 1935, was called “miniature photography”. In its day it was the micro four thirds, the poor cousin to the medium format and plate cameras that attracted all the pros. Now, after all these years, that little 35mm film frame is “full frame” and is the standard on which our new digitals are based.

After our rather wet and cold outing, Adam returned to his bathroom darkroom with the three films and processed them at the same time and in exactly the same way. What would we find? I had to wait all of 24 hours to get the results.

Adam does the difficult bits

Cameras: Technical comparisons:

Throughout the afternoon, Mike and I juggled a little between our three cameras. I was pretty stubbornly glued to my M3, and Mike held onto his M7. But the III was passed between us throughout the day. All these cameras handle beautifully, and they each defiantly exude a sense of belonging to their respective eras.

First, let’s compare the M3 and M7, since it is these two cameras that have the most in common with one another. I’m heavily biased towards the M3; and that’s not just because I have one. My film photography obsession emerged at a time when I was a student, and funds meant that Leicas were very much an object of distant desire (even the film systems). This naturally meant I had researched them to death, and in my mind, I had the M3 and DR Summicron firmly set as a future target. Let’s take a quick rundown of some of the differences between Leica’s first rangefinder, and its current analogue model:

- The first difference is a big one: the M7 has an electronic light meter built in, and an aperture-priority auto-exposure mode, in addition to full manual. The M3 is fully mechanical: Manual is the only option. Either you meter with an external light meter, or you use your eyes to dial in the desired exposure.

- The M3 has framelines for only three focal lengths: 50mm, 90mm and 135mm. They show up either as just the 50 (if a 50mm lens is mounted), or in pairs of 50/90mm (if a 90mm lens is mounted), and 50/135mm (if a 135mm lens is mounted). The M7 has paired framelines for 28/90mm, 35/135mm and 50/75mm lenses; automatically displayed according to which lens you use.

- The M3 has the most magnified view of any Leica rangefinder: 0.91x magnification. The reviewed M7 has a 0.72x magnification (like most), although options for 0.85x are also available from Leica, on request. While the M3’s viewfinder can be a pain for anything wider than 50mm, it is a true joy to use with a 50mm lens. The view is expansive. The M3 also has the most accurate framelines / parallax correction system of any M camera ever made. The M2 is apparently a close second in this regard.

- The M3 has a focal plane shutter made from rubberised cloth; an all mechanical affair. The M7 has an electronically controlled cloth shutter curtain. The latter is more accurate when it comes to accurately controlled exposures, but requires a battery in order to fire at all speeds.

- The M3 has a self-timer; Leica removed this from all rangefinder cameras subsequent to the M4.

- If your M3 was made before March 1958 (like mine), you will have a double-stroke film advance. The M7 has a single stroke lever. The main difference aside from the obvious, is that the double-stroke advance mechanism is quieter; they do not make a stepped clicking noise on their return, like single-stroke bodies. Hardly important, but a difference, all the same. Quieter still, is the advance knob of the Leica III and other screwmount bodies.

Handling: A shooting experience:

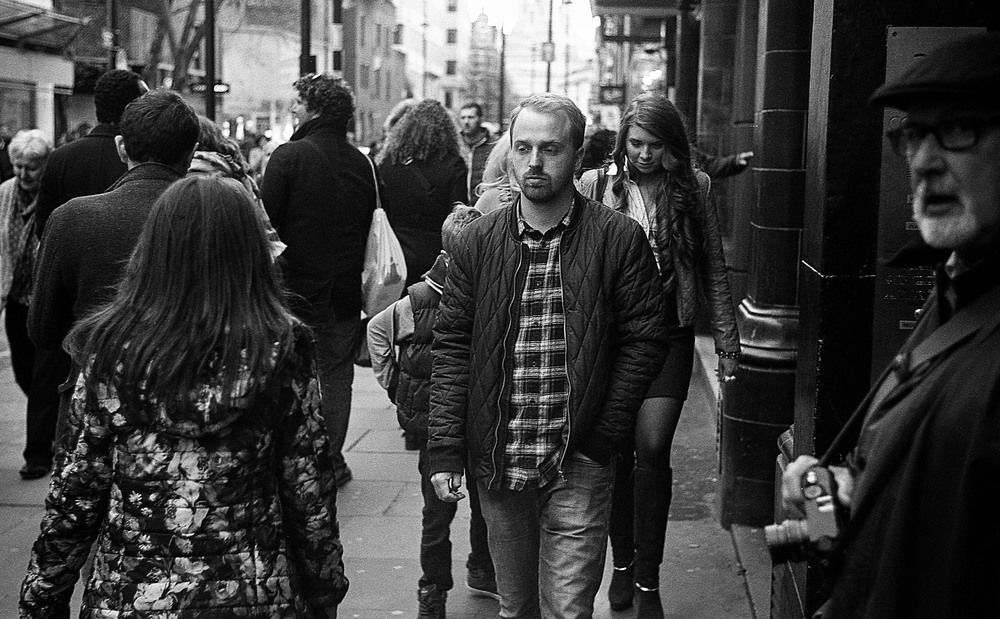

Handling-wise, the two Ms were very similar. Both are a joy to use, supremely quiet and stealthy, offering a clean view of the world behind their perfectly polished glass windows. Focusing is perhaps a tad easier with the M3 due to the larger rangefinder patch, but overall comparable. The big advantage the M7 has is the light meter. If you require one of these, the M7 (or an M6, an MP or, even, an M5) most certainly wins.

The Leica III is on the other end of the spectrum, and requires that you focus through its dedicated rangefinder window while framing the shot through a second window. The latter has no framelines, no parallax—it is designed for use with a 50mm lens. If you wish to use lenses of different focal lengths, framing is best achieved with a dedicated external viewfinder. Something particularly pleasant about the III’s split focusing system struck me after my first go with it.

The rangefinder is enormous. We are not dealing with a small square patch in the middle of the frame, but rather a much larger, dedicated viewfinder. I found that I could focus on my subject’s feet at the very top of the rangefinder’s view. This afforded a little extra discretion, since you didn’t have to lift the III as high up as the Ms to achieve focus. The III is also considerably smaller than both the M3 and the M7; I could get close, and my subjects didn’t really notice me photographing them. While some may find its operation more cumbersome than the borderline aeronautically smooth M system, there is a charm to using older screwmount Leicas that really has to be experienced.

The process:

On the walk home, it struck me that this was by no means a scientifically accurate comparison between the three cameras: It was an artistic one. Despite this, it would be best to factor in as many commonalities as possible to even out our results. We used the same film in all three cameras, and thus it would make sense to process the three films at the same time, under the same conditions.

A quick detour past West End Cameras, allowed me to get a three-film capacity developing tank. I was covered; or so I thought, only to find when I got home, that the film reels were not included with my purchase. I therefore resorted to my old two-film capacity tank (whose leaky lid loves drenching me in fixer), and a steel one-film capacity tank (forever my favourite system). The two M films were loaded into one tank, and the III film was loaded into the second steel tank. I mixed up 1.5 litres of Ilford ID-11 (1:3), and had the two tanks staggered by 30 seconds to allow me sufficient time to pour solutions in and out of each. This was my first time juggling two film processes at once. It will probably be my last.

After a very tense half hour of sacrificing my clothes to the fixer demons, I had three films that had all been processed at the same time, temperature, and with the same amount of agitation. Unfurling the dripping film strips revealed a string of perfectly formed photographs—on all three films. I could not have been happier. The M3 produced 38 full frames, while the M7 and III produced 37 each. [Ed: That’s because Adam spends an inordinate amount of time loading his film so that not a millimetre is wasted].

The results:

While images were scanned and aesthetically processed in Lightroom, one thing was immediately noticeable to me. All lenses appeared to perform very comparably in terms of sharpness. On well-focused shots, they were all razor sharp. Where they differed was in contrast. Inevitably, they would each render colours differently, too; however, contrast will be our focus in this monochromatic review. The old Summar was the least contrasty of the three. It produced considerably flatter images than the two Summicrons, both of which were comparable in this regard. That said, the Apo definitely had darker shadows, and brighter highlights. There is a nice, progressive contrast gradient that chronologically underpins these lenses. Photographers of the ages, it would seem, became increasingly fond of higher contrast in the pursuit of more ‘finished’ looking images—right out of the camera.

Final thoughts:

All three systems are brilliant. Since I always manipulate my images, then there is maybe something to be said for the flatter rendering of the Summar. It captures everything and, if the artist wishes to adjust the images, then that’s what the darkroom (or Lightroom) is for. Straight from the camera, this optic will certainly add a blatantly nostalgic footprint to your work.

Perhaps for my tastes, though, there is something about shooting with a Summicron. It brings an intrinsic sense of confidence to the photographer, a defiantly reliable performance guarantee. I love my Dual-Range, but I also love the results of Mike’s stellar Apo ‘Cron. Make no mistake: This is a fierce lens, with spades of uncompromised sharpness on offer. The DR is a remarkably close runner-up in this regard—quite a feat for a lens manufactured nearly 60 years ago—and adds its celebrated tonal signature into the mix.

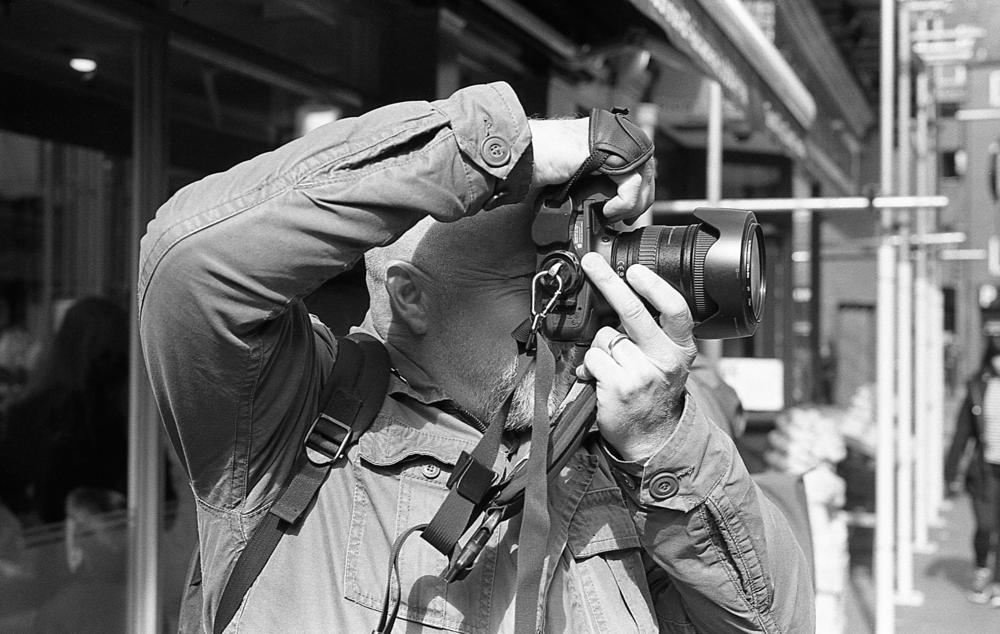

Any afternoon spent taking photographs with Mike Evans is a thoroughly enjoyable, inspiring one. We explored the streets of London, with three beautiful film cameras which, in turn, attracted the keen gaze of photographers along the way. And perhaps most importantly, we actually managed to take one or two photos that I know I certainly won’t forget. That warm fuzzy feeling you get when looking at that deceptively tiny memory on a strip of dripping wet gelatine for the first time: For me, that’s what it’s all about. Whether your instrument of choice is an old pinhole camera or a finely crafted Leica, it is how they manifest your artistic vision that really matters.

- Subscribe to Macfilos for free updates on articles as they are published. Read more here

- Want to make a comment on this article but having problems? Please read this

- We are grateful to Adam Lee for his time and sterling efforts in processing the three films. You can follow Adam here: Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Can’t add to anything that has been said here by either the writers or the commenters…

I would say that from the example of the the three pictures outside the restaurant that the M3/DR Summicron demonstrates utter sublimity.

However, I strongly suspect that given its head on a modern digital Leica body, that the APO would pull ahead.

The perfect Leica photographer’s set up might well be M3/50DR, MD/50APO and a spare Monochrome body…

Plus a few extra lenses for special occasions.

Unless one is a collector Mike 🙂

You could be right on the ideal setup. But instead of the Monochrom perhaps an SL would be the better choice–the full-on, modern, digital experience.

Interesting article, thanks. Just a quick note: not all single stroke M3’s have the ratchet mechanism for the return stroke. Those between 919.250 and 963.000 have a completely quiet (spring based) return and are quietly sought out as you can single or double stroke and have the quiet return. Also late numbers in that range have the enlarged rear eye inlet.

Thanks, David. I wasn’t aware of this detail and it is useful to have it for the record. I wouldn’t call myself an expert on the M3 but the good thing is that there is always someone out there who is. Many thanks.

Thank you for this fact, David – I had always wondered about the SS M3. I didn’t know that some of them had quiet return levers, but it would make sense, since it was the first step away from the DS advance lever, which was quiet by design. I sort of wish they continued this feature into all Leica’s. It’s so much more classy to the touch, and one less click to worry about when shooting photos of wary subjects. Thank you for the useful insight and information. Hope you enjoyed the post!

I agree with you Mike. There are a number of camera shops in Dublin selling film SLRs at very low two figure prices. Most come with a nice 50mm lens attached. They are largely aimed a student market, as students of photography have to learn about film use. The only film SLR, which I still have, is a Nikon FM3A which I bought in mint condition as a collector piece (the last fully manual Nikon) but I use it to take pictures quite a lot. I find, though, that with my eyes a rangefinder is much easier to use for focusing nowadays. I think back to the years when I used a manual focus SLR without a care in the world but the years have not been kind to my eyes. I have had two operations on my left eye but my right eye which I use to focus with seems to have come out in sympathy with the other eye.

William

Fine article and a good read. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks, Richard and thank you also for your Facebook share. It is always good to have feedback whether positive or not, but especially good to get the thumbs up.

Thanks so much for that, Richard – you are a brilliant photographer, so that means an extra special amount. Glad you enjoyed it!

A lovely article by Mike and Adam. My tuppence halfpenny worth below.

My preference would be for the M3/DR combo, but on film the output differences are very marginal. I think that the Summar holds up well. One of the great joys of the Summar (I should know, I have seven of them) is shooting wide open or nearly there. Even if the image is soft, you get the most wonderful swirly ‘bokeh’ and a truly ‘ancient look’. Using film is problematic in bright light as you have to stop down the lens to avoid over-exposure, particularly with a camera that only goes to 1/500th. It is actually easier to get such effects with the Summar on a digital camera. I have a large number of LTM cameras and only a small number of them can produce absolutely accurate speeds at all speed marks. This lack of speed consistency sometimes results in grainy negatives in low light. A CLA will definitely help an LTM in the speed consistency department, but they will not be as accurate as a modern camera. That should not affect the output (pictures) which will have a unique signature charm. Of the cameras used here, the M7 should produce the most accurate exposures but a finely tuned M3 should not be far behind.

My reason for liking the M3 is the 0.91 rangefinder/viewfinder which aids my poor eyesight in the focusing department. I have both a double stroke and a single stroke M3. I like them both, but I marginally prefer the double stroke. The only thing that would improve it, would be if it did not have a self timer. I don’t like self timers (which I don’t use anyway) under my right hand when I am holding a camera. I have a button rewind M2 which has no self timer which I really like using; if only it had an M3 viewfinder! There’s no pleasing some people!

I also have an M7 and, despite the excellent automation(it produces really lovely exposures), I have never really bonded with the camera. For an M with an exposure meter, I prefer the M6 which feels smaller and lighter in my hands. I don’t have the APO lens; I have a plain vanilla 50 Summicron and the DR Summicron. The photos taken by the APO here look just as good as those taken with the DR, which in my view is the best Leica 50 lens I have used apart from the modern 50 Summilux. Those who have used both, have said that the 50 APO is better than the Summilux on digital and so it should be. It is a more recent lens, designed for digital use. For film, the 50 DR has a tonal character, as mentioned by Adam, which is hard to beat and using more modern designs probably does not add very much.

The photos above are all excellent as is the developing and processing. They have a look and feel that you just cannot get with digital. Film is a great ‘equaliser’ and however much I have spoken about different lenses and cameras, most of what is shown above is down to the photographers. The lovely series of the young couple of restaurant staff in the street illustrates this very well.

William

A wonderful appraisal from a Leica expert. Thank you so much for that, William. Interesting to see that we both feel the same about the magical M3/DR combo. It’s a real treat. I don’t have a host of other Leicas here to compare it to, but I did own an M4 for two years prior to this, and the difference is clear. I’ve also had the fortune to play with a lot of other film Leicas, and still feel the solidity and smoothness of the M3 and it’s wonderfully characterful, tack sharp DR synergise into a winner for me. Glad you enjoyed the article; really sorry to hear about your eyesight, but also glad to hear the M3 is helping make the most of your passion for photography.

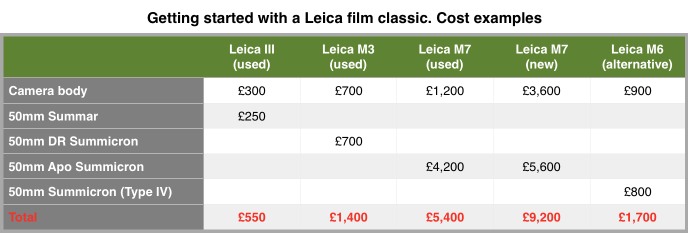

I think it’s worth mentioning that while Leica film cameras, of almost any age, are great choices for modern film photography, the entry price for film is surprisingly low. The examples we quote in the article–from £550 to a staggering £9,200–are based on the equipment described in the article. But if you can’t run to the starting grid on old Leicas, why now buy yourself an old Olympus OM-1 or OM-10. These are great little cameras and can be had, complete with an excellent 50mm lens, for as little as £25-40. Take a few shots, compare the results and you will be surprise how good they are.