This article is adapted from original information supplied by Leica AG.

The history

The Leica M has been around for more than sixty years. Whenever technological advances gave rise to a new generation of the rangefinder camera, designers determined how best to reconcile the new technical requirements with the distinctive appearance of this camera series. As the company’s most definitive product, the design process of a Leica M requires an entirely different approach to any other camera made in Wetzlar.

The M calls for subtlety, as well as a sense of respect and responsibility towards a design tradition that has been passed down for over 60 years. Therefore, M design can only ever be about evolution, not revolution. Consequently the M10 is immediately recognisable as a true M. In fact, those who have remained loyal to their analogue M models may find that the M10 seems like an old friend – after all, it is the first digital M to adopt the more compact form factor of its analogue predecessors.

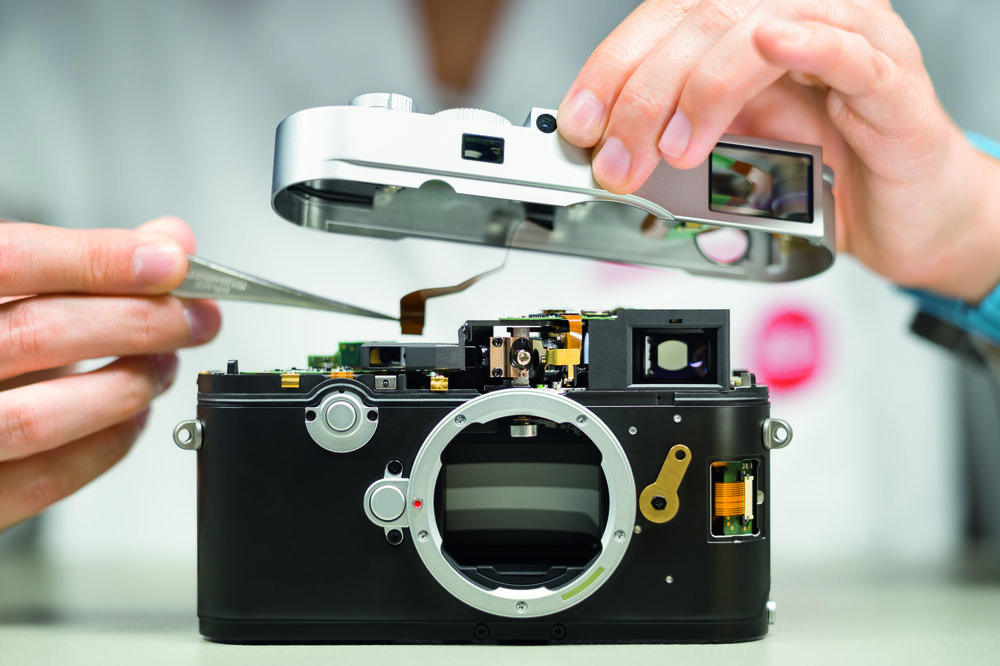

The characteristic design of the Leica M10 is perfectly complemented by the skilled artistry of its construction. Supreme-quality materials, largely crafted by hand, not only indicate a suitability for everyday use and long-term durability even in adverse conditions, but are also a confirmation of the ‘Made in Germany’ quality seal. The top and base plates are milled from solid blocks of metal, then ground and polished by hand in a 40-minute process. The camera’s inner workings are safely housed within an extremely stable magnesium-alloy chassis. Almost all add-on components and operating elements are also made of metal. The display sits behind scratch-resistant Corning® Gorilla® Glass, with specialist rubber seals offering additional protection against drizzle, dust and sudden weather changes.

Longevity is also guaranteed when it comes to the M10’s interior: all components have been carefully selected and tested to ensure long-term durability out in the field. More than 50 adjustment steps are required to build a camera with the utmost mechanical and optical precision such as the M10. It encompasses around 1100 single components – including 30 that have been milled from brass, 126 screws and 17 optical elements. The assembly process spans from connecting the roller-lever with the rangefinder, to calibrating sensor and image board, all the way to attaching the back shell and top plate.

Years before the term ‘sustainability’ had been coined, M cameras and their legendary lenses gave rise to a set of enduring values to be passed down the generations. And the same still applies today: M10 photographers are able to work with a lens from 1954 – and indeed with any lens from the over 60-year history of the M system. Then as now, the M system continues to stand for the unparalleled quality of craftsmanship Made in Germany.

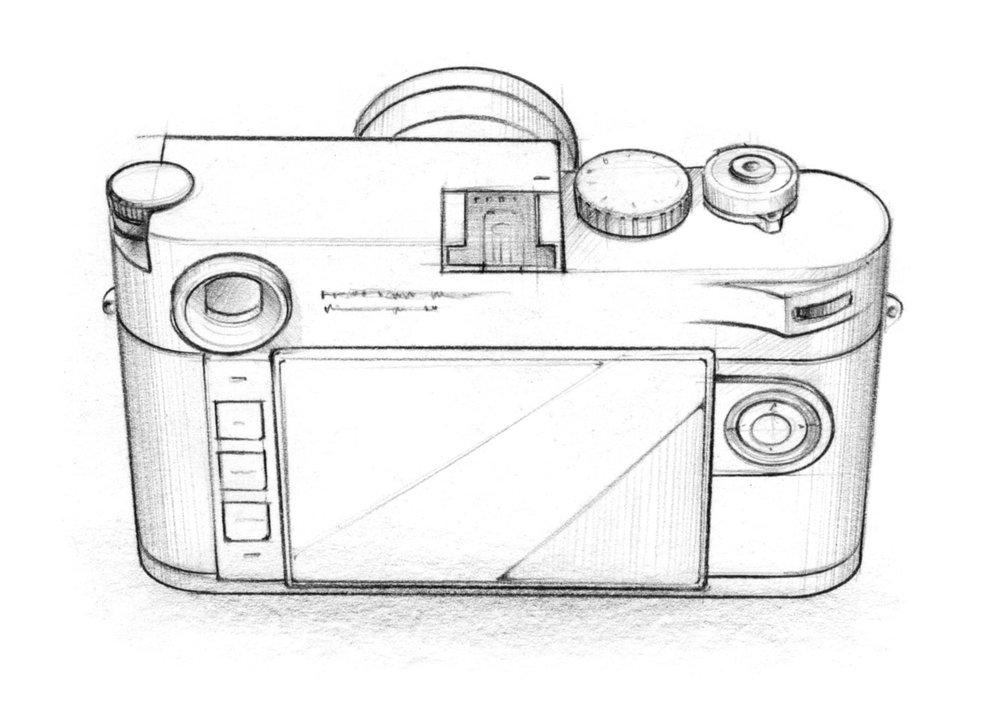

The design process

Contemporary sensor technology has facilitated a digital M that looks exceedingly like its analogue predecessors: lean and slender, the new M10 represents an M entirely geared towards digital rangefinder photography. To achieve this, a number of technical challenges had to be mastered.

Whenever Leica M customers were asked what they would like to see in a new model, a slimmer body was among the most frequently cited requests. From the M8 through to the M (Typ 240) and its sister models, digital M cameras have always been a few millimetres deeper than their analogue predecessors. And so the new M10 fulfils an ardent wish among M photographers, with dimensions that once again equal those of an analogue M.

The previous discrepancies in size were borne out of technological limitations: in the M system the flange focal depth (the distance between mounting flange and image plane) is predetermined – and consequently, so is the position of the sensor. The latter requires a certain amount of space, as do the circuit boards and the display. An analogue M, by contrast, only has to accommodate the comparatively thin film, a pressure plate and the rear panel.

So when developing the M10, Leica’s engineers found themselves having to meet two essentially opposing requirements: to further improve the camera’s electronics, and to simultaneously accommodate this enhanced, high-performance construction within a smaller body. This was made possible by the application of state-of-the-art PCB technology, which supports ten layers of conduction paths within one circuit board. In addition, the recent availability of more highly integrated, miniaturised construction elements reduced the amount of space required.

Another factor was that the lens mount, which cannot be re-positioned, now protrudes slightly over the front of the camera. While barely noticeable in itself, this required an adaption of the rangefinder mechanics, or more specifically the transmission between roller lever and the optically effective beam path of the rangefinder – a measure which actually further improved the rangefinder’s settings accuracy.

Analogue M cameras feature an ISO settings dial which up until now has never been replicated on a digital model. Given that its traditional position on the rear of the camera is occupied by the display, a new solution was needed to offer M10 photographers direct access to setting the ISO value. The new ISO dial has now taken the place of the film rewind lever, which had obviously been superfluous on digital M models.

The greatest challenge when designing the dial was to ensure it was convenient to use, yet at the same time impervious to accidental adjustments. As a result, the dial is locked when in standard position; to set a new ISO value, the photographer must pull the dial straight upwards with two fingers, subsequently pushing it back down to secure the selected setting.

While the M7, for example, offered a 0.72-times viewfinder magnification, this was reduced to 0.68 times in digital models. With the M10, Leica have not only reinstated a 0.73-times magnification, but have also improved the position of the entrance and exit pupils, and expanded the field of view by 30 percent. Once again the M10 does not merely return to the parameters of an M7, but actually manages to supersede them. The photographer benefits from improved viewing comfort (particularly for those wearing glasses), as well as a greater degree of certainty and fewer misfocused images.

The sensor of the M10 has retained the 24 megapixels that have become established as an excellent balance between resolution and light sensitivity. The camera’s ISO range, on the other hand, has been extended in either direction compared to its predecessor: the lowest ISO value of 100 now enables the fast Summilux lenses to be used at open aperture even in daylight, truly bringing out their unique character. On the other end of the scale, the distinct reduction in image noise allows for a maximum ISO setting of 50,000, which makes the M10 the perfect Available Light camera. Even at high ISO levels, the M10 continues to deliver pristine image files. Also, side effects such as colour shifts on the edge of the image and vignetting have been reduced even further.

Although the M10 is clearly dedicated to rangefinder photography, focusing on the basis of a live-view image remains an additional option, which makes it easier to utilise focal length ranges below 28 mm and above 135 mm, and also opens up the possibility of macro photography. While the integrated display can be used for these applications, best results are achieved with an optional electronic viewfinder which attaches to the hot-shoe. The M10 is compatible with the Leica Visoflex (Typ 020), a viewfinder which provides an exceptionally clear, large-sized image and natural colour rendition.

The M10’s range of functions has been consciously limited to those that are essential to rangefinder photography – in other words: still photography. This is not to say that Leica have decided against the concept of recording videos with an M. In fact, the company will continue to offer the Leica M and M-P (Typ 240) partly for the purpose of keeping the video option available to customers. Another reason is that these models offer interfaces which can be upgraded via the multi-function handgrip – something that is not provided for the M10.

The new approach to data transmission is now based on WiFi, thereby also enabling the photographer to save images directly onto the iPhone and share them with others. Streaming the live-view image and releasing the shutter via the app opens up exciting new applications and unusual perspectives, as well as providing greater control – for example in the case of selfies, or when shooting a group photo from a tripod. Professional applications and studio work, however, will continue to require tethered-shooting solutions, for which the M/M-P (Typ 240) with multi-function handgrip remain the most suitable option.

______________

- Subscribe to Macfilos for free updates on articles as they are published. Read more here

- Want to make a comment on this article but having problems? Please read this

I actually feel a little teary at how well Leica have done with this new design. It’s like they have personally answered all my misgivings about the M240 and custom-made me a perfect little gem of a camera.

I had been poised to take the Leica plunge, and the M-D looked perfect as it ditched all the fussy buttons and menu clutter. However, I had a nagging doubt that was this: surely a top end camera should be able to do everything I want? Giving up macro and closeups in particular was an issue for me.

I also disliked those little ‘nubs’ above the strap eyes on the M240, and loved the M60’s smooth lines which didn’t have them. I loved the M-D’s iso dial. And yes, the 240 is a bit thick, as everyone says. I thought it could not possibly be a big deal, but it is very cool to be thinner. And my left eye couldn’t see the 28mm framelines, which I think it something the M10’s 0.72x will solve too …

Oh, and I was worried the top LED would flicker in my eye, but it turns out to be a light sensor for the screen. It’s the bottom LED that indicates image being written to card.

So here we have the simplified, nubless, skinny, ISOdialled, big-findered, liveview M I was imagining. And a customisable menu too.

So instead of an M240 and a D750, which would have given me thre required functionality but unbearable ugliness, or even a perfectly formed M60 (now £24000!), I can have it all with an M10. So Leica have saved me thousands of pounds here. (And you don’t hear that very often!) … 🙂

Thanks Mike for all your great posts. You have taken me to the edge of the abyss …

Thanks! I agree with you that the M10 combines the best of the rest and I am looking forward to making it my camera of the year (after the Q and M-D in the past two years.).

I would like to turn this into a little article if you don’t mind. Can you send me a direct email to mike@macfilos.com so I have your name and a few details (such as where you are based).

Mike

Very interesting. Who says that modern cameras are not ‘computers with lenses’? I do wish, however, that the ‘design team’ had put exposure compensation rather than ISO control on that wheel.

William

My initial thought was that I would have preferred to see an exposure compensation dial rather than an ISO adjuster. However, on second thoughts (and bearing in mind my M-D experience) I think they’ve done the right thing. Once you have it set up correctly, the right-hand thumbwheel does a good job on exposure compensation. It’s often better to be squinting through the viewfinder to see the effect of compensation (when using the EVF, that is). With the rangefinder in play the exposure compensation is always a bit hit or miss.

I don’t agree about the system aspect. When I see a scene, it is much easier and quicker to make an exposure adjustment before I raise the camera to my eye. I hate ‘pfaffing’ around with controls with the camera to my eye. In my experience this is much slower and messier to use. Maybe it is just me, but I prefer physical controls on the camera body that I can see. In my view the Leica system here is an example of ‘style over function’.

On the other hand, I totally agree with you about the EVF giving a preview of exposure. This is something that is totally undersold by manufacturers, particularly in respect of the older generation of photographers who have grown up with optical viewfinders.

William