When I was in Berlin in March I decided to pay a visit to the former border crossing point at the Friedrichstraße station. I passed through this station countless times in the two decades before the opening of the Wall in 1989. I had, and still have, friends who live in the eastern part of the city and I invariably had to visit them. They could never visit me, for obvious reasons.

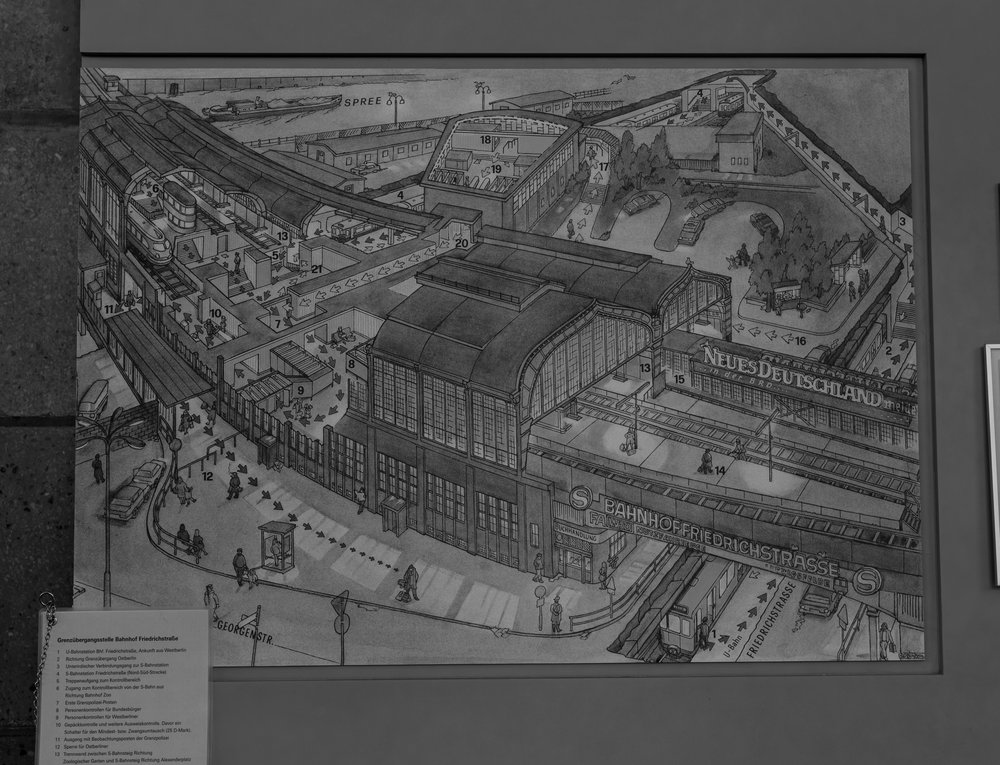

Friedrichstraße, on the S-Bahn, was the main crossing point for international foot passengers. On the many other occasions I travelled by car I had to use the Kochstraße crossing at the other end of Friedrichstraße, near Stadtmitte. Kochstraße is immortalised as Checkpoint Charlie.

But approaching by train meant alighting at Friedrichstraße and passing through the border controls erected by the ironically mis-named “German Democratic Republic”. Getting in was never easy, although considerably less of a problem than getting out.

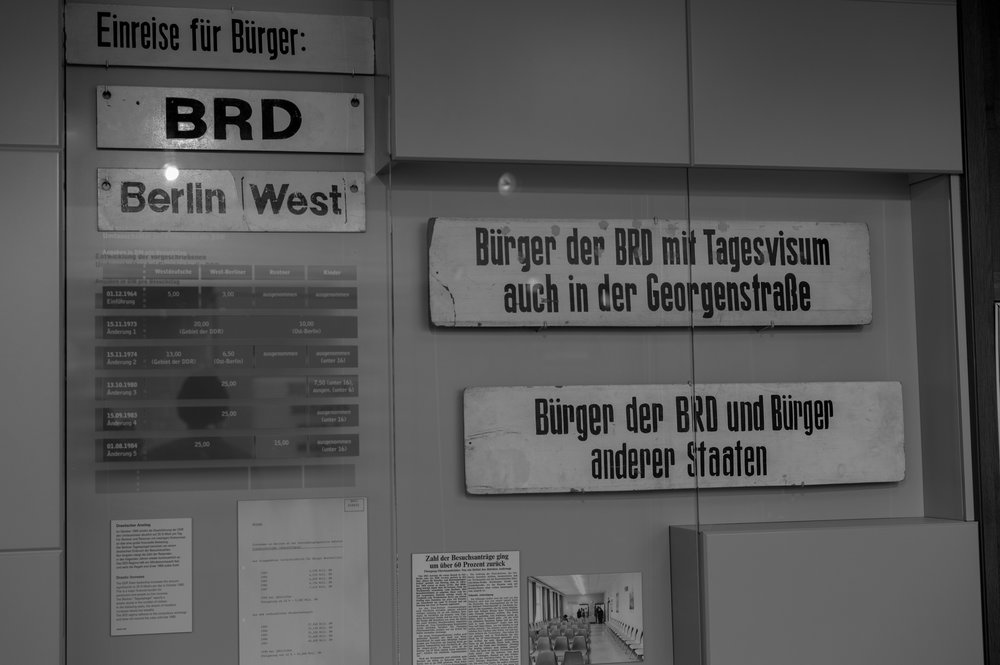

There was the visa fee to pay, of course, and then a compulsory currency conversion into Ostmarks at the official rate of one to one (the real rate was more like ten to one). It was a one-way conversion — old hands knew to spend up because any unused Ostmarks would be confiscated or dropped into the charity box at the exit control.

Then there was customs control where subversive slices of sausage or anything printed in the evil “West” would be confiscated and surreptitiously eaten, read or burnt. The odd banana and orange was permitted, strangely enough, but I have seen white-haired old ladies reduced to tears over 250g of ham. Kids even had their comics confiscated lest they corrupt the young communist pioneers.

Anything and almost everything was condemned as “not permitted in the German Democratic Republic.” In those days they were concerned with any popular “wessi” products. Western visitors were often asked to smuggle in a pair of Levi’s jeans and that was about the only way for young people to get hold of these desirable status symbols.

Emerging into East Berlin in those days was truly like stepping into another world. It was a parallel universe, similar but subtly different to the bustling West Berlin. For a start, it didn’t bustle; and there was a complete lack of advertising, except for Communist slogans plastered hither and thither. It was Berlin frozen in time in 1945. Even the two-stroke Trabant cars could have dated from that decade. And the smell of all that two-stroke oil had to be experienced to be believed. But I will cover that in a later article. For the purposes of this story I am focused on getting out of the GDR after the visit.

The clearing point for “Ausreisende” (outgoing passengers) returning to the west through Friedrichstraße consisted of a sweeping glass concert-hall of a departure building. It had been constructed, no doubt, to impress visitors and remind them of how good things were in the GDR. It was almost as if this glimpse of modernity would cause departing visitors to forget the rest of what they had experienced.

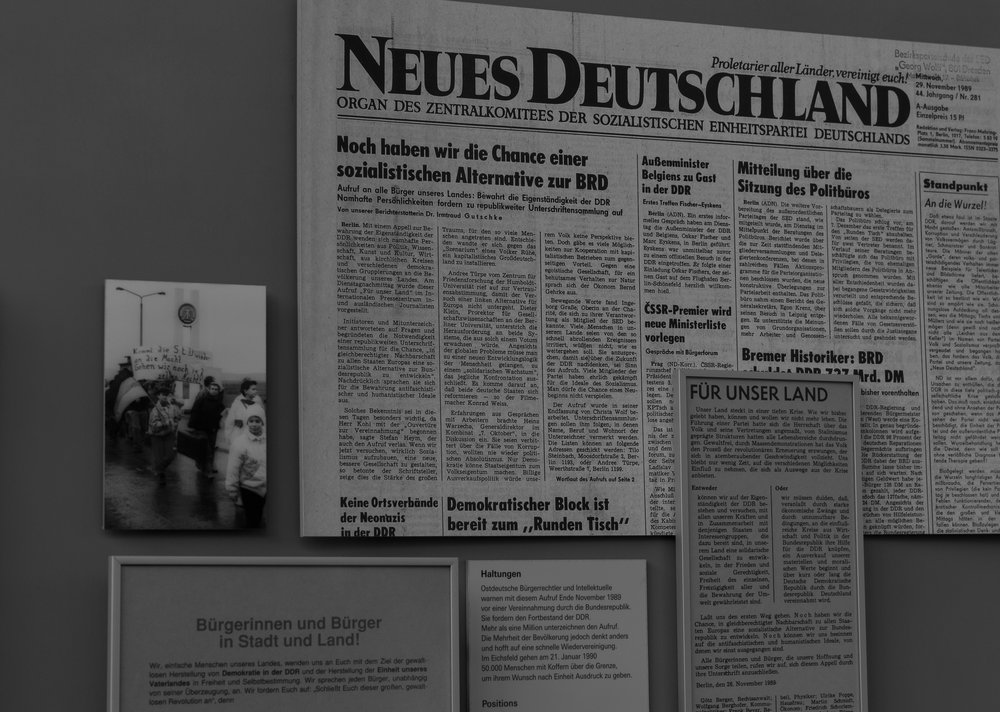

Unfortunately, this glittering 1960s edifice was the scene of mush anguish as East German citizens said goodbye to their friends and relatives as they returned to the decadent West. Much to the annoyance of Comrade Erich Honecker and his Politburo, the shining hall soon became known universally as the Tränenpalast or Palace of Tears. It became a symbol of oppression, a sad indictment of the totalitarian socialist regime that kept a city (and country) divided for over 40 years.

Good news, as I discovered, is that the Palace of Tears is still there and still functioning, but now only as a free museum. The exit to the west is now abruptly closed by a glass panel. But all the old partitioning and control booths are there, together with a goodly collection of period memorabilia. The atmosphere is considerably happier than it used to be in the old days. Not a tear to be shed, except perhaps by older visitors who can remember the reality.

It is impossible for a younger person to visit this museum and really understand what it was like to pass through the hall in abject fear. It is now all so prosaic and dated. Even I, as a British citizen, always felt uneasy when I passed brought the controls. Perhaps I had said a bit too much to my friends in the city — I must have had a Stasi file as long as Erich Honecker’s Swiss bank account — or committed some other innocent transgression. On several occasions I expected to be told to get out, never return, or worse. But, much to my surprise, nothing ever happened. There was anxiety for me, as for anyone else who passed through the “palace”, but fortunately I never personally shed a tear.

On my way back to the U-Bahn station I passed a poster featuring the young Karl Marx. Now there was a man who had a lot to answer for.

As always, even today there are apologists for the hideous East German regime. Some older people look through their rose-tinted glasses and see cheap prices for basic foodstuffs (when available, but that isn’t remembered) or hark back to a time when there was no crime and no road traffic accidents (simply because such decadent happenings were never reported). With hindsight, it is tempting to cherrypick the few good points about this socialist regime. But I wonder how many current apologists have actually experienced the reality, perhaps in places like Venezuela, Cuba or, even, North Korea. I can speak from experience, and I didn’t like it one little bit.

Photographs by Mike Evans, Leica Monochrom Mk.I and 50mm Apo-Summicron-M

_____________

What a walk down memory lane, Mike! Not exactly a tree-lined lane, but one I recognise so well from the sixties and the seventies. I met my (Danish) wife taking her to Check-point Charlie in my 2CV. That was a period when we were in East Berlin (travelling daily from the west of the city) at least once a year to share themed conversations over several days with friends from Western and Eastern Europe. We went East because they couldn’t then come West. Our friends were what we might call critical citizens of the countries they were living in. Their issue was not flight but to find a way of living in and with the system that ruled as humanely as possible. (And, of course, our issue was the same in a less obvious, less oppressed way.) We did not fawn on them, and they did not spend their time yearning for the fleshpots of the West. We had serious conversations in which viewpoints clashed and differences were acknowledged and explored with no glossing over. It was a privilege to be part of such a gathering and such long-standing friendship which continues up until to-day. Sorry, that’s not a very photographic comment, so let me finish by saying: when I look at your pictures, I am there. They even SMELL right !

Wonderful and thanks for all that insight. To some extent it mirrors my experiences.

In the late 60s I made friends with a motor cycle fan in East Berlin. We shared an interest in bikes but, of course, he couldn’t travel. I sent stickers and badges and suchlike and, of course these were highly prized in the east. Then, one day, I went across the border and met my friend and was introduced to his parents and his girlfriend. None of them spoke English, so here was my opportunity to polish my German.

Over the next two or three decades I visited several times every year and we all got on so well. In the meantime, my motorcycling friend got married and a daughter was born. Then, in 1989, I was there when the family came over to West Berlin for the first time. I have so many memories of the intervening years and I must write an article one day. My heritage is a Berliner accent, or so I imagine.

Look forward to installment, magnificent first person closeup history!

So those rumours were true… you really did work for MI6.

No comment

Hi Mike:

Thank you very much for the interesting article. A large part of my family comes from Berlin and some of them had to suffer under the heel of Ulbrich, Honnecker and Co. Berlin is an interesting city, full of history, worth traveling to with the camera in hand.

I leave a link to an essay like thing I wrote (and photographed) about an other significant place in Berlin.

Keep up the good work.

Mike, another great photo essay.

It’s good to hear this from someone who made the crossings. So much of the feel of history is lost when we can no longer hear the first person narrative.

Excellent article Mike, many thanks.

I wonder whether Comrade Corbyn has the same system in operation in Islington?

Gotta keep the populists out somehow!

Comrade C is one of those intellectuals who fawned over all the old Soviet satellite countries back in the day. He and his cronies were wrong on just about everything then and they haven’t anything learned since. Come the revolution, of course, he knows he would be near the top of the tree, a member of the nomenklatura, a Parteibonze who would drive down the reserved lane in the centre of Whitehall in his black Zil. So it’s no wonder he wants to create a socialist paradise in England’s green and pleasant land. The Politburo never have to queue for oranges.

Great photoessay, thanks for sharing.

If you want to see if you actually do have a Stasi file, you can request it from http://www.bstu.bund.de/EN/Home/home_node.html .

Thanks, Dave. I intended to do this some years ago and never got round to it. I will have another look and see what’s involved.