It was my recent acquisition of a Grubb lens made in Dublin around 1855, shown above, that led me to pen this article about two remarkable Irish and Anglo Irish families. In particular, this involves two father and son duos where the fathers were born in the same year (1800) and the sons both passed away in the same year (1931).

The contributions of the Grubb and Parsons families in the fields of optics and astronomy are well known, but they also had achievements in other fields such as the consistent printing of bank notes and the creation of the steam turbine. The 19th century was truly a great time for inventors and creators and what we might call ‘renaissance men’ or ‘polymaths’ who could, seemingly, turn their hand to anything and succeed.

Let us start with Thomas Grubb, the creator of the lens pictured above, who was born into a Quaker family in Portlaw in County Waterford, Ireland, on 4th August 1800. He started out in Dublin in 1830 as a modest billiard table manufacturer. He moved on into making telescopes and lenses at his works at 6 Canal Road, Dublin.

I would love to show the building which contains this plaque, but what was up to recently a nice whitewashed 19th century bungalow, now functioning as a restaurant, has recently been covered by hideous planks, making it look like a garden shed. I will spare the reader’s eyesight on that score. When I arrived there the plaque to Thomas Grubb was actually hidden on a wall behind an open door.

I might add at this stage that Thomas Grubb also became the Chief Engineer at the Bank of Ireland where he developed a consistent technique for the printing of bank notes.

The telescope market was mainly where he concentrated his own business, but he also produced lenses for the growing photographic market and sought to patent his creations. The following is a discussion of my recently acquired lens and lens technology in the mid 19th century. Those not interested in these topics can skip to the second paragraph after the last photograph of the lens below.

This lens is an Aplanatic (form of aspherical lens) Meniscus Landscape lens. It has a focal length of 30cm (almost 12 inches) and it would have been used on a large wooden camera on legs to produce 10 x 8 inch images. The lens number and the patent engraving can be seen clearly in this photo.

It can be seen that this lens is in a focusing mount (not all lenses at that time had that feature) and the ‘helicoid’ marking is visible on the side of the barrel.

For aperture control many lenses at that time used inter-changeable washers to give different stop sizes. I am not sure if the washer in this lens could be changed as I cannot remove the top piece. Later versions seem to have removable brass caps or pull out pieces which could be used to change the stop-to-glass distance. The washer can be seen clearly in the following photo, but I have not been able to calculate the stop size. I believe that stops running between f14 and f31 were used in Grubb Aplanatic lenses. Exposure times were very long, but were helped when the wet-collodion process was introduced during the 1850s

In 1858 John Waterhouse introduced the Waterhouse Stop, which involved a slot in the lens body into which different sized stops could be dropped. This is often seen on Petzval portrait lenses which were made by a number of manufacturers, including Grubb. These were later replaced with the iris diaphragm which we are familiar with today.

Some people have asked me what am I going to do with this lens. My intention is just to keep it as a collector’s item. I had been looking for a lens made by Grubb for some time as they were produced in Dublin, just a few miles from my home. It is certainly not mountable on any camera made today unless it has a bespoke mounting board on the front and can produce 10x 8 inch images. Just to demonstrate the size of this lens, here it is beside a typical Leica lens of today, a 35mm Summicron

On 26th March 1858 Grubb presented a paper to the Combined Scientific and Artistic Committees of the Royal Dublin Society (RDS; I am a member of the RDS myself today) in which he claimed that his Aplanatic lens design could eliminate or even over correct spherical aberrations. He is said to have been disappointed some years later when Dallmeyer (who had been working with Ross in London) obtained a patent for the Rapid Rectilinear lens which, some say, carried elements of Grubb’s aplanat design.

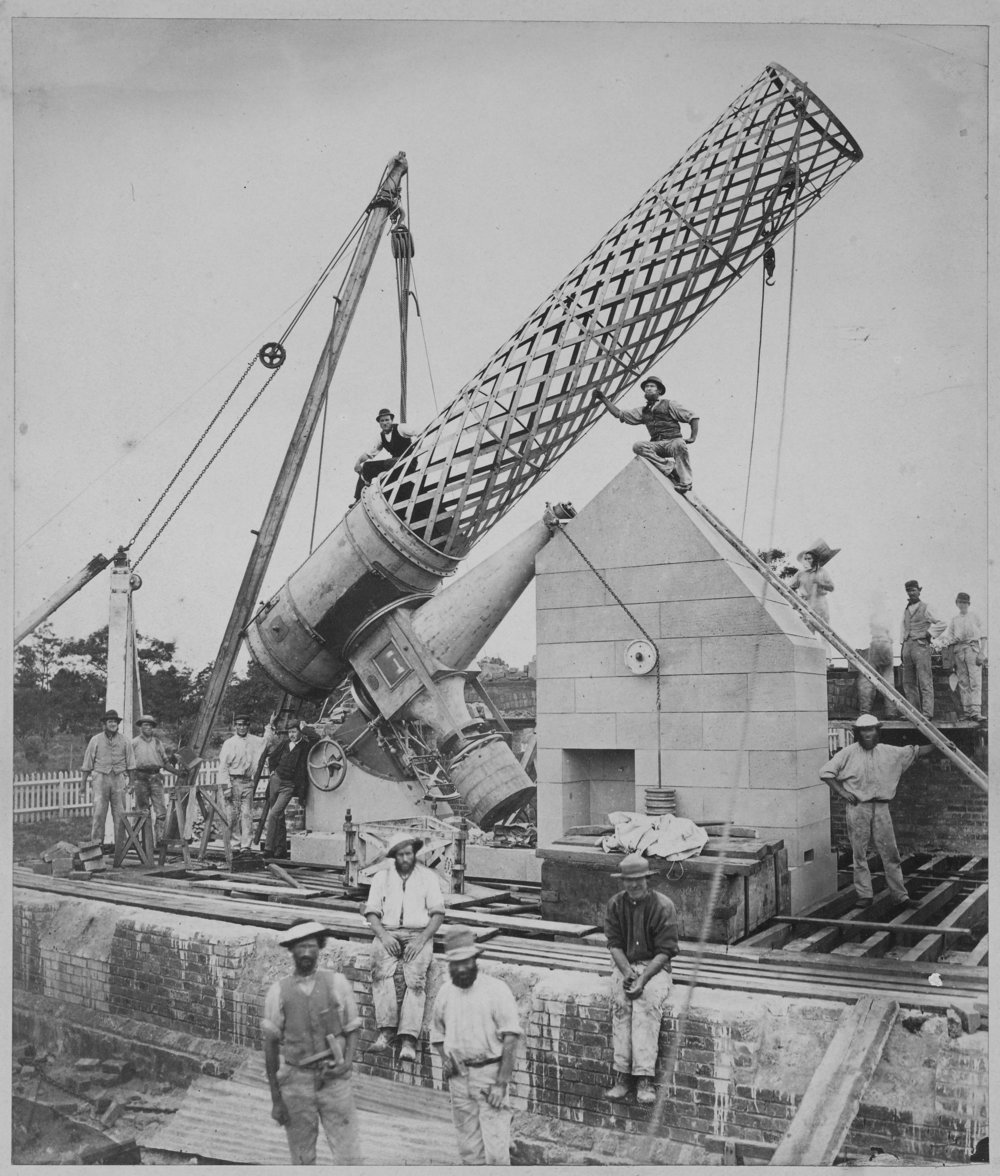

I would now like to take a step back in time and introduce the Parsons Family. William Parsons was born on 17th June 1800 in Yorkshire , the son of an Irish peer. The family seat was in Birr (pronounced ‘Burr’ and formerly called Parsonstown) County Offaly. Parsons obtained a first-class degree in mathematics in Oxford in 1822 and inherited an earldom ( 3rd Earl of Rosse) when his father died in 1841. He set about building the largest (focal length 52 feet and aperture 6 feet) astronomical telescope in the world, nicknamed the ‘Leviathan of Parsonstown’ , in the 1840s. The previous largest telescope in the world had been the one at Markree in County Sligo, Ireland which had an equatorial mount built by Thomas Grubb. Here is a contemporary painting of the building of the telescope in Birr.

Rosse did a lot of the work at Birr and the creation (casting grinding and polishing) of the speculum mirror was done there. He had some difficulty with creating solid mounts for the thee-ton mirror and this is where Thomas Grubb stepped in and helped with some creative levered support solutions for a mirror of this size. I visited Birr to see the telescope a few years ago and, even today, it is a most impressive instrument

It has its own ‘building’ (walls 23 feet apart, 40 feet high and 71 feet long) which does not move, but the telescope was capable of some altitude and azimuth movement via a ‘universal joint’.

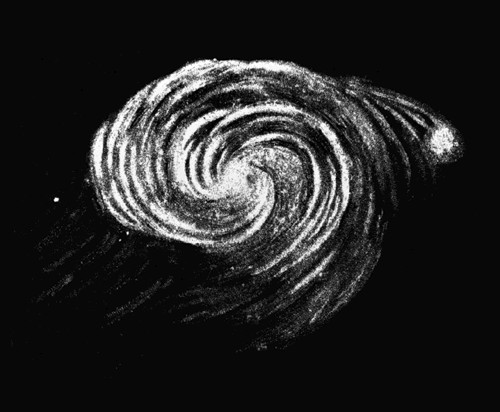

In 1845 Rosse was able to sketch the picture below showing the correct structure of the ‘Whirlpool Galaxy’.

Here is a photo of the same galaxy taken by the Hubble Space Telescope

Insert Photo 10

Rosse was the first astronomer to establish the spiral nature of galaxies. He was also able to see other features clearly for the first time. For example, he was the person who gave the ‘Crab Nebula’ its name as he was able to see its features more clearly than any other astronomer at that time. For the remaining part of the 19th century, the Birr telescope remained the largest telescope in the world, although further evolution in telescope design rendered it somewhat outdated.

The Earl’s wife Mary, Countess of Rosse, was a very active photographer. She joined the Dublin Photographic Society which had been founded in 1854 by Thomas Grubb and others. She was the second female member after Miss M Grubb, who is presumed to be Thomas Grubb’s daughter. Mary Rosse was soon winning prizes for her photography and in 1859 she won the Society’s Minerva Medal . Her photo laboratory is preserved in Birr Castle and remains as it was in her time. It is thus a treasure trove of Victorian photographic equipment and techniques.

The large camera in the left foreground is similar to the type of camera for which my Grubb lens was intended.

William and Mary Parsons had thirteen children but only four of them survived into adulthood. Their youngest child was Charles Algernon Parsons(later Sir Charles), born in 1854, who went on to become the inventor of the steam turbine. His ship design, the Turbinia, which was built in 1894, was at that time the fastest ship in the world by a large margin. The ship famously turned up at the Spithead Review in 1897 where it easily outran existing Royal Navy ships. Here is a model of the ship on display in Birr Castle.

The original is now on display in a museum in Newcastle. In the yard at Birr Castle on the day that I visited I saw the following remains of an old steam turbine.

Parsons set up the Parsons Marine Turbine Company in 1893. This was later absorbed into C.A. Parsons which became a leading manufacturer of steam turbines, particularly for the power generation industry. Many nuclear power stations today have Parsons steam turbines. The company was located at Heaton in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and underwent a number of structural changes after the death of Sir Charles in 1931. It is, currently, a division of the Siemens group.

It is now time to go back to the Grubb family. The youngest son of Thomas Grubb was Howard Grubb (later Sir Howard), born in Leinster Square, Rathmines, Dublin in 1844. During the 1860s Thomas began to hand over control to Howard who had been training to become a civil engineer. Under Howard, the Grubb Telescope Company made great strides. Grubb telescopes and mounts were installed in Dunsink and Armagh observatories in Ireland and in the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. The company also manufactured telescopes for observatories much further away from home. One of the most famous was the great Melbourne telescope

This telescope was not without its teething problems. Eventually, those problems were resolved and the telescope gave many years of service, during which time it was modified several times, including the installation of CCDs in the 1990s on Grubb’s original equatorial mount. It was damaged in a bush fire in 2003, but there is an ongoing project to restore it.

When the Melbourne telescope was ordered, the Grubbs moved to a larger premises in what is now Observatory Lane in Rathmines in Dublin

Most people passing through Observatory Lane today on their way to the Leinster Cricket and Sports Club or to their houses or apartments , or just to park their cars, probably have no idea that this was once the site of the foremost large telescope factory in the world, whose products can still be found all over the globe.

Today Observatory Lane is a rather anonymous place .

I did think, though, that this door and wall looked rather ‘ancient’ and I could just about imagine Thomas or Howard Grubb coming through the door or passing by this wall.

Thomas Grubb died in 1878 and Howard continued to develop the company after his death. By the time of the First World War the Grubb Company had become a supplier of periscopes to the Royal Navy and also made telescopic gunsights. Perhaps as a result of the 1916 Easter Rising and also, possibly, because of fear of a German invasion of Ireland, the company moved to St Albans in England in 1918.

After the war, the demand for some of the Grubb products declined and by the mid 1920s the company was in serious difficulties. At this point Sir Charles Parsons stepped in with funding to form the company of Sir Howard Grubb and Parsons Limited. Its headquarters were moved from St Albans to Newcastle where it continued to provide first-class optical items for observatories all over the world until 1985, long after both Sir Howard and Sir Charles had died in 1931. This plaque is on the wall of Sir Howard’s home at 13 Longford Terrace in Monkstown, Dublin.

The company continued to have a tremendous reputation and it maintained the Grubb tradition as is obvious from this lovely video from 2005 where Howard Grubb is referred to as a ‘Rembrandt of the Lens Making Age’ by a former staff member of Grubb Parsons. We can definitely forgive him his enthusiasm when he refers to Sir Howard as an ‘English engineer’. The lens polishing machine, shown in this video, is an original Grubb item and the old manual shown is marked Rathmines, Dublin 1895.

The impact of the creations and endeavours of these two illustrious families continues long after their time and even though neither company still exists, their achievements will not be forgotten.

As part of the commemoration of those achievements, the Irish Academy of Engineering presents a Parsons Medal with a portrait of Sir Charles Parsons on the medal to those achieving excellence in the development of engineering.

Earlier this year my younger brother, Professor Tony Fagan of University College Dublin, was a recipient of the medal. He is seen here in the centre receiving the medal from the current Earl of Rosse, Brendan Parsons, who is on the left. The current Earl is a half brother of the late Earl of Snowdon who was a renowned photographer and the husband of Princess Margaret.

Through this medal award, the Parsons name lives on as a mark of engineering excellence in Ireland.

This article started from my acquisition of an historical lens made in Dublin in 1855, but it has taken me through an amazing series of inventions and creations by two families whose paths crossed on many occasions, leading to the development of science and technology and the world in which we live today.

The following is a brief bibliography

- A Lens Collector’s Vademecum, Dr Alex Neill Wright, available for download.

- Photography in Ireland , The Nineteenth Century, Edward Chandler, Edmund Bourke Publisher

- Impressions of an Irish Countess, The Photography of Mary Countess of Rosse 1813-1885, David H. Davison, The Birr Scientific Heritage Foundation

- Victorian Telescope Makers, The Lives and Letters of Thomas and Howard Grubb, Ian S. Glass, Institute of Physics Publishing , Bristol and Philadelphia

- William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, Astronomy and the castle in nineteenth-century Ireland, Edited by Charles Mollan, Manchester

- Two Fathers and Two Sons by G.E. Manville, General Manager of Sir Howard Grubb, Parsons & Co Ltd, available for download from here.

_______________

Mr. Fagan,

I belong to a living history group (North Texas Civilian Historians). The persona I’m creating is that of an 1860-62 traveling photographer and tutor. I have a few period lenses and now building prototypes of the cameras/equipment I will be using for the period processes. I found this thread while looking for Grubb lens references. Thinking the logical place to look for them is Ireland so I’m writing this. Are there any shops or other sources where I could buy a Grubb lens? I have seen some as straight lenses and some with focus knobs. How do you date them and is there a chart/list of the serial numbers? I would want one manufactured before 1862 to go with my others so dating is rather important. I’m open to suggestions. My thanks, Ira Medcalf, Fort Worth, Texas, USA iraimages@aol.com

I presume that the persona is that of Carleton Watkins who famously used a Grubb lens in the 1860s to take photos of Yosemite, long before Ansel Adams got the same idea.

6 Grubb lenses were put up for auction a few weeks ago at Breker Auction in Germany. At least 3 of these are now sold, 2 in the auction, one of which I purchased, and one after the auction. I will send you a mail with a link to the auction items. I know that Breker will sell items that were unsold after the auction, probably at the start price.

As a matter of interest I am going to see the Grubb Telescope at Dunsink Observatory at the end of next week along with fellow members of the Royal Dublin Society. I may bring along my two Grubb lenses to ‘meet’ their much larger ‘relative’.

One final addendum is that Sir Charles Parsons, the inventor of the steam turbine and also mentioned in my article, has now been honoured on a recent silver proof coin issued by the Central Bank of Ireland. I’d like to see Thomas and Howard Grubb similarly honoured.

William

Dear William,

As professional (Irish) astronomer living in Paris I found this article really wonderful and I learned a lot of things I didn’t know about Grubb and Parsons. When I am giving talks to students I always enjoy telling them that, in fact, the world’s largest telescope was in Ireland at Birr for many years! Of course, one of the problems with the “Leviathan of Parsonstown” was that the mirror made of metal and therefore not very shiny.

There are many famous Grubb and Parsons telescopes around the world, and quite a few of them are still in active service. The one I have visited the most the 1.93m telescope at the Observatoire de Haute Provence (OHP), which was constructed in 1957. There were actually three copies of this telescope: the two others are in Cairo, Egypt and Victoria, Canada. The OHP 1.93m was used in 1995 to discover the world’s first extra-solar planet.

So, thanks again for this interesting and informative article !

Best,

Henry J. Mc Cracken

Thanks Henry. I really appreciate your comments as you are a professional astronomer and can fully understand the contribution of the Grubbs and Parsons families. I had thought about putting a list of the observatories with Grubb or Grubb and Parsons telescopes all around the world into the article but it would be quite a long list. The easiest one for most UK based readers to see is the telescope in the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. Here in Ireland we have Grubb telescopes in Dunsink near Dublin, Armagh Observatory and in University College Cork.

You are right to tell your students about the great Birr telescope. The achievement of the Earl of Rosse in building that telescope in the 1840s was truly astonishing and it gave this world new views of previously unimaginable sights across the universe.

I see that, like me, you are a Leica fan and that you like shooting film. I would really like to find some way to use my Grubb lens but I somehow doubt that I will get around to this. From the examples I have seen from Carleton Watkins who used a Grubb Aplanatic to take photos in Yosemite in the USA in the 1860s, it seems to be a fine lens. Rudolf Kingslake who wrote the standard text on 19th century photographic lenses said that while the Grubb lens will eliminate spherical aberrations, there are some issues with coma.

Thanks once again. I presume that you are in some way related to the man of the same name who founded the United Irishmen.

William

Dear William,

Thanks for the comments. Yes, it would be lovely to use a lens like your Grubb lens on a Leica. Since starting film photography with my Leica I have been amazed at people like Mandler who made such excellent lens designs without using computers, and the film in your story reminds me that was true also for telescope designers. There are a lot of interesting parallels between telescope design and camera lens design, which I am sure you are aware of. As I understand it, the introduction of aspherical surfaces in the last twenty or thirty years has really revolutionised our ability to make wide field, very bright and compact telescopes. Of course taking pictures on the street during the day smaller apertures are more than sufficient !

As for the link to the other Henry Joy, well maybe :-). The destruction of the civil records office in Dublin during the Irish Civil war has made it hard going far enough back, and it’s nice to maintain the mystery !

Thanks Henry Joy. If official civil records are destroyed, sometimes parish records can provide what is required. Please feel free to get in touch if you want to follow up on that.

That Grubb lens would not fit on any Leica directly and the image size would be very large; Carleton Watkins shot 18×22 inch images with his Grubb Aplanatic in the 1860s. A friend in the Leica Society has, however, just shown me how he mounted a Petzval style brass projector lens (possibly made by Bausch and Lomb) on a small Fuji digital camera using a bellows with a Minolta screw-in mount. So it seems that I need to do some more research on this subject.

The aspherical lenses which we have today would not exist were it not for the pioneering work done by Grubb, Petzval and Dallmeyer and many others. If, however, you go back in time you will find that some of earliest work on optics and astronomy was done by Arab pioneers such as Ibn Sahl and Ibn al-Haytham about 1,000 years ago. The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, where I lived for a number of years, has a wonderful collection of items related to early Arabic astronomy including astrolabes and other items.

William

‘William and Mary Parsons had thirteen children but only four of them survived into adulthood. Their youngest child was Charles Algernon Parsons(later Sir Charles), born in 1854, who went on to become the inventor of the steam turbine. His ship design, the Turbinia, which was built in 1894, was at that time the fastest ship in the world by a large margin. The ship famously turned up at the Spithead Review in 1897 where it easily outran existing Royal Navy ships. Here is a model of the ship on display in Birr Castle.’

I remember reading somewhere that in the act of outrunning existing Royal Navy ships that it was feared that there would be a collision between Turbinia and some of the Spithead fleet … To avoid this Parsons’s speeded Turbinia up!

Thanks Colin. From what I have read, this sounds like an early example of a ‘dog and pony show’ to impress ‘the powers that be’. It is said that Turbinia turned up ‘unannounced’, but the outcome was a further high speed trial attended by the Admiralty which led to orders for two destroyers with Parsons Turbines. It seems that Sir Charles Parsons was not just an excellent engineer, but was also an adroit businessman.

William

Very interesting article William. Have you considered submitting it for publication to e.g. Astronomy Now or Sky at Night magazines?

Regards

dunk

Thanks Dunk. I am just a humble photographer and collector of vintage cameras and lenses. I would be terrified to put this into a heavyweight astronomy magazine. You will have seen my younger brother in this article, but I have an older brother who has been studying astronomy for over 50 years. I will ask him what he thinks.

I look forward to seeing you at the Leica Society event in Chester in a few weeks from now.

William

WOW,