The great inflation in Germany reached its sorry peak in 1923 and no one was immune. At the Leitz factory in Wetzlar it was the same as everywhere else. A week’s wages would turn to dust before the pile of notes left the factory gates. As in other parts of Germany, wives would stand at the factory gates to grab the rapidly inflating currency and run to buy anything — anything — that could later be turned into more cash to buy food. We’re talking billions and trillions in a world gone mad.

Stories, many no doubt apocryphal, abound. The cup of coffee that cost 50 billion when it was ordered but had risen to 100 billion by the time you’d stirred it twice. The shopkeeper with his barrowload of cash who was mugged for the wheelbarrow. The cash was left behind. There is no end of amusing trivia but, at the time, this hyperinflation was anything but funny.

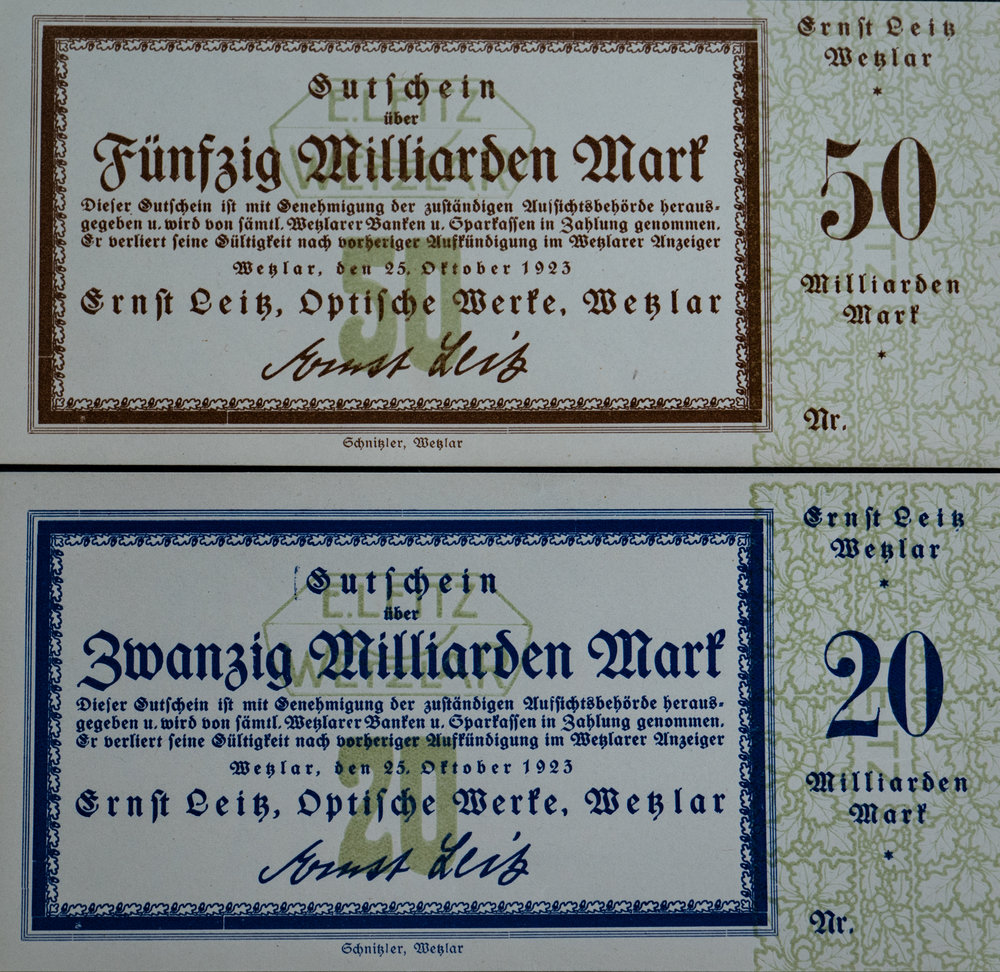

Leitzmark

So acute was the shortage of banknotes that companies throughout Germany were driven to printing their own Gutscheine, or coupons, to provide a modicum of liquidity. The Ernst Leitz optical works in Wetzlar was no exception. I came across the above examples of the “Leitzmark” on a recent visit to Red Dot Cameras in London. There’s no end to the fascinating stuff Ivor Cooper has stashed away in the shop museum. These two coupons are in absolutely pristine condition and, I am sure, were never issued. Note that they don’t even have numbers printed on them. It’s the mind-boggling denominations that impress. Incidentally, a milliard was the term for what is now known as the “short billion” or the standard billion used today. It’s equivalent to 1,000 million. The so-called long billion, which was used even in the UK until the mid-seventies, was even bigger — no less than a million million. If we’d stuck with that even Bill Gates would have been a relative pauper.

Armed with these 50 billion and 20 billion notes, Leitz employees could rush out and buy a loaf of bread. And the rush was literal. Stop to tie your shoelaces and the 50 billion loaf would cost 70 billion.

These Leitz Gutscheine, which are typical of thousands produced by commercial concerns during the period, state that they are issued with the authority of the local government and may be exchanged at various local banks for real money. A notice in the local Wetzlar Anzeiger newspaper served to cancel the notes when their time was up.

Reckoning

The two coupons were issued in October 1923, towards the end of the period of hyperinflation which had devastated Germany from June 1921 onwards. In this case, of course, there was an unavoidable cause with its roots in the Treaty of Versailles and the impossible levels of reparation forced on Germany. But it was the wartime borrowing by the German government that really lit the fire. We’ve seen similar situations recently in countries such as Zimbabwe and, currently, in Venezuela which are self-inflicted by reckless borrowings and loss of confidence following unrealistic hard-left socialist policies. It’s the old money tree analogy. At some stage there comes a reckoning. For Germany and, at a local level for Ernst Leitz, the reckoning came in 1923.

By November that year, just a few months after these Leitz Gutscheine were printed, the US dollar was worth an impressive 4,215,500,000,000 German marks. The situation was stabilised by the introduction of a new currency, the Rentenmark, backed by bonds indexed to the price of gold. A year later, in August 1924, the rate of exchange between the old currency and the new was set at one trillion Reichsmark to one Rentenmark. Result, in the words of Dickens’ Wilkins Micawber, was happiness. But only for a short time as it turned out.

Here’s a full description of the great inflation.

____________

Sounds like the Great Depression and dust bowl era here in US with wall streeters throwing themselves out of sky scrapers.

A timely article, Mike, if ever there was one. It is good to see that war has a price, but, of course, savers suffer badly in such circumstances. You should copy this to the White House as a lot of people on the other side of the pond may be worried about the long term future of their 401(k)s. Globalisation has come with a price, but so too will isolationism. Thankfully, most Governments, with a few exceptions such as those which you have mentioned, have now learnt how to control inflation and its effects.

One other interesting case that will come up in the coming years will be the oil producing economies who have pitched their Government budgets to a particular level of oil price. There is no sign of oil prices going back up to previous levels anytime soon. The oil producing countries will have to take measures to curb their Government spending and/or introduce taxes to offset the shortfall. A lot of oil producing countries have pegged their currencies to the dollar (which is the trading currency for oil) which was probably a wise precaution on their part.

Global financial systems are, of course, a lot more sophisticated than they were in the 1920s and should assist in preventing such hyper-inflation, certainly for as long as such systems can remain global. The strains on global systems are all too obvious right now.

William

We have our own Corbyn and friends who greatly admire Venezuela’s socialist policies while ignoring the carnage that has resulted. Unfortunately many young people with no knowledge or appreciation of history have shown a willingness to help him make the same mistakes that were made before. We are condemned to repeat our mistakes, it seems. But that’s politics and I try to steer clear of the subject on Macfilos.

Well said. My contribution was all about economics, of course.

William