“….you don’t know what you’ve got

‘Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot.”

Joni Mitchell certainly wouldn’t have been thinking about photography when she wrote and sang those words in her Big Yellow Taxi classic song of fifty years ago. But I’ve been wondering lately if they might ring true for an aspect of present-day photography. Specifically, the obsession with noise reduction in cameras and digital images.

Film in the Last Millenium

Back before the turn of the century, now a long, long time ago, film ruled supreme in photography. And even when light levels were low, photographers still practised their art, pushing film developing chemistry to the limit.

With that came grain in photos — the classic grainy image. Sometimes the grain was fine, sometimes it was quite overwhelming. The level depended primarily on the chemistry of the film and its processing. But photo folk generally then accepted grain and sometimes embraced it. Graininess often provided an ethereal mood to an image. It was certainly not spurned, and it was treasured in many cases.

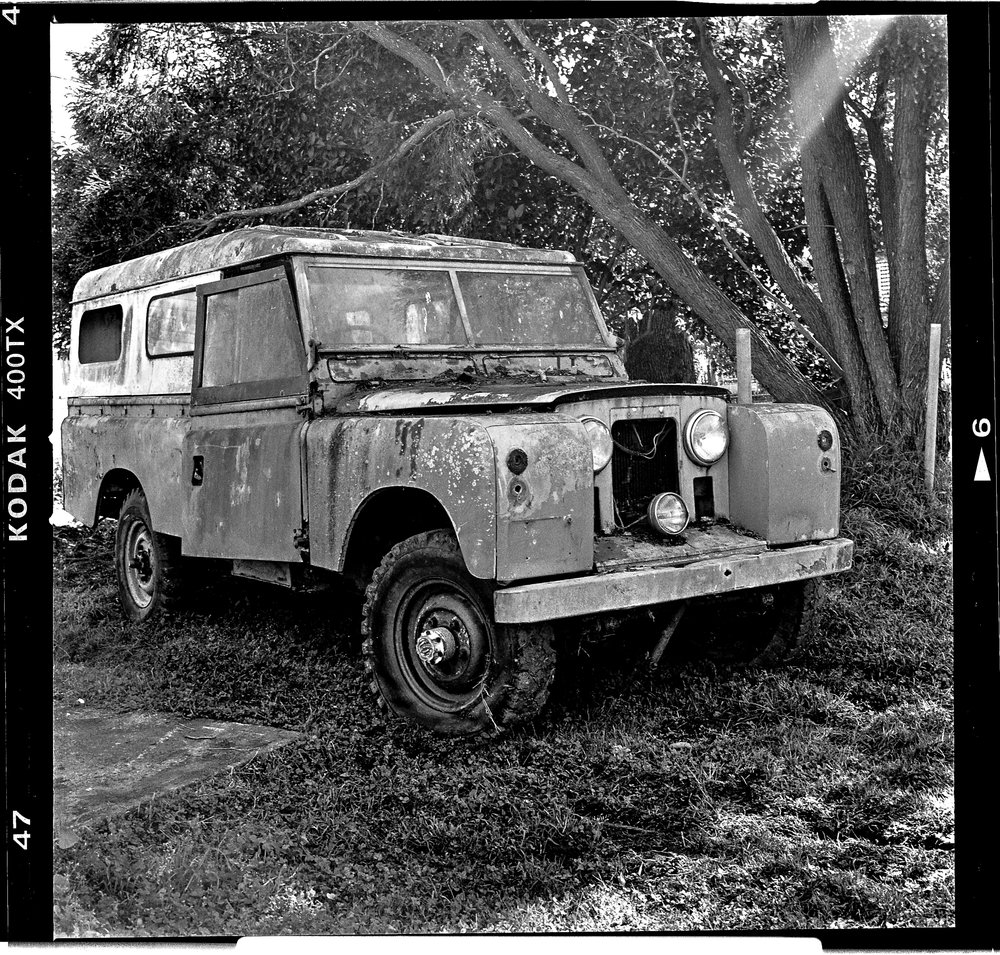

Below: Three scanned film images kindly provided by John Shingleton from his collection. Grain looks lovely in the black and white shots, and it doesn’t detract from the colour film image either. As he retrieved them for me, John began to wonder whether he should have sold the Hasselblad film camera used for these shots. And just to set the record straight, he isn’t sure that he can agree with me on the sentiments of this article – but I’ll continue to work on him over coffee! Wax on, Wax off, Grasshopper. (Click images to enlarge)

That was Then, Now is Now

Fast forward to the digital photography of the 21st century and we might call that graininess “noise”. It is different certainly, but it could be considered the digital equivalent. And it is generally not accepted as it might have been in the days of film.

Camera manufacturers go to lengths to program noise reduction into their firmware, even at the expense of image sharpness. The settings of nearly all cameras have mid levels of noise reduction applied as a default. And most of the extensive reviews of new cameras strive to point out inherent noise at ISO levels that film photographers could have only dreamt about. Noise is undesirable and bad!

The above night-time images were shot hand-held with a little Fuji X20 one night in Hong Kong: Looking up towards our room on the 34th floor of the Hyatt, and no shortage of luxury vehicles on the road outside. There’s a high level of noise in these shots, bordering on chroma issues, so they could be considered as being over the top in terms of noise. But I’ll keep them anyway. (Yes, it was T’editor Mike’s recent trip that made me remember some noisy shots that I took one evening in Hong Kong two years ago, and it was Jason Hannigan’s recent article in Macfilos about his X20 acquisition. Click on the images to view full screen.

The Human Condition

Bear with me on this section – I’ll get there. We now live in a world where advertising exhorts us to fear germs. We are encouraged to use antiseptic sprays on every horizontal surface in our houses, maybe even on vertical surfaces too, and certainly on kid’s schoolbags lest they bring home the plague from the playground. My hypothesis is that in photography we are too often obsessed in the same way with the removal of noise in digital images.

No, at our house we do not use antiseptic sprays crazily on every surface, and we carry hand sanitiser in our pockets only when we are trekking or travelling in areas of the world where an extra shot of cleanliness is important. Maybe that approach is also relevant to psychologically coping with noise in digital photography. We should value the image, not its technicals.

Certainly, digital noise is not the same as film grain, both physically and quality-wise in images. To some photographers, noise is an anathema. But some writers have suggested that a small amount of digital noise can give an image a “film-like” look. Others point out that the physics of noise reduction compromises sharpness and clarity, so it should be balanced.

Yet we still pixel peep for noise and use it as a parameter in choosing and using a digital camera. Maybe we should become more tolerant and be accepting of low levels of digital noise. In fact, it’s the subject, composition, perspective and light in a digital image that is by far the most important for outcome, not whether every individual pixel has captured the light with clinical accuracy.

Above are more night shots which were taken in the Kowloon area of Hong Kong. The Fuji X20 was set to auto everything, it made its own decisions. But just putting a bit more light into the images provided me with some keepers. Certainly, there’s noise from that little 2/3 sensor, but I find that it helps me to remember that evening with a somewhat painterly quality. Click on images to view full screen.

Let’s Ponder

So, here’s something to maybe think about – Have we become too obsessed about sanitising noise out of our images? Cameras with smaller sensors will generally produce low-light images with noise, much as the film photography produced low light images with grain. But does that mean we should throw away our older, tiny sensor cameras, or stop using them in low light? I’d propose that there’s nothing wrong with a bit of noise. In fact, it can even add a certain quality and sometimes enhance the look of a night-time hand-held shot.

As photography rediscovers film we will again see more instances of those noisy images when film speed is pushed. Sorry, I meant to say grainy images. Maybe let’s sometimes enjoy it even with our digital photography.

Last Words

Joni Mitchell’s words strike a resonance as we all get more and more super clean, low noise, ultra-real images:

“They took all the trees

And put them in a tree museum

..Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

‘Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot”.

Above: From the archives. Lots of noise here, from tiny Sony cameras in 2012 on the way to Everest. Hand held, no flash, taking the cameras to the limit: An early morning cuppa as the sun hit the side of the tent at 4,500 meters (Sony DSC-W350). And three monkeys waiting for dinner at 5,400 meters with the temperature at minus-15 centigrade. Hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil…..just too bloody cold! (Sony DSC-W80). Noisy images yes, but a chronicle of special moments. Click to see full size.

___________

I have to say it is an interesting theory, and I agree that done right – regardless of media (film or digital) it can be amazing and provide some authentic feel to the whole scene. However forcing it ala some digital processing packages just looks wrong.

What struck me more, is that despite any noise, is that an image is an image, and done well regardlessly will draw in the viewer.

So on a final note, other than to say thank you to John for sharing a few iconic film shots from the Shingleton back catalogue – Where you up Everest covertly auditioning for a part in the next film attempt of Roald Dahls Caterpillar from James and the Giant Peach.. Sorry couldn’t help myself. My wife didn’t understand why I was chuckling, and then I showed her – she laughed with my explanation.

Excellent stuff Wayne. And I bought a Df for the fact it shoots better images in low light.. lol.

Lol here too Dave.We hadn’t ever thought of Roald Dahl’s Caterpillar for that image.But now that you mention iy we can also see it as a pic from our granddaughter’s book "The Very Hungry Caterpillar". Just Wiki that title, you’ll see why. You’ve put smiles on our faces 🙂

And I look forward to seeing some images from the Df. Those monster-sized individual pixels should do a truly great job in capturing light.

Ha ha ha I remember the very hungry caterpillar book, my daughters used it in their learning – a long time ago now. But you are right, its as much a ringer as my James and the Giant Peach connection.

First Df image I wanted to publish is in my flickr account. its very personal to me, and has huge defining meaning that at the moment I probably won’t talk, or write about – maybe one day in the future.

“..Sometimes the grain was fine, sometimes it was quite overwhelming. The level depended primarily on the chemistry of the film and its processing. But photo folk generally then accepted grain and sometimes embraced it..”

“..sometimes embraced it..” Mmm. I’ve never understood that. Grain seemed to come to prominence with “gritty realism” photos on 35mm film of the north of England. Shirley Baker comes to mind, Jane Bown, John Bulmer, Don McCullin, Bill Brandt and so forth. These people sometimes shot in poor light with ‘fast’ film, with prominent grain as a result. The grain never seemed to be a distraction ..it was just what you got. Like liquorice is the flavour of liquorice.

But then it became a ‘style’ ..push-processing Tri-X film to get more grain ..pushed to 800 or 1600 ASA (ISO) to emulate the “pros”; the apparently successful, published photographers.

When the capabilities of digital included built-in effects, “grainy black-&-white” became a ‘scene’ option, and (some) photographers tried mimicking grain. Software like ‘Nik Effects’ and ‘Alien Skin’ offered “film-like grain” for digital pics to make them look – supposedly – more like film and therefore more “authentic” ..though, of course, that’s daft; it’s so absolutely in-authentic!

(But video editing software offers “scratch and grain” or “jitter and weave” to make digital movies look like badly projected cinema film!)

..It’s all just nostalgia.

But why “embrace” grain? ..or digital noise. It’s simply a side-effect of how the picture’s made. Accept, yes, but “embrace”? Why?

If you have to walk more slowly uphill because it’s tough going, would you walk as if it’s “tough going” when on the flat? If running to catch a bus or train makes you short of breath, would you present yourself as short of breath in normal, everyday life in order to pretend to be running for a train?

So why pretend that digital photos are low-light film photos? Why “embrace” digital noise? I don’t get it.

I accept what a camera gives me when I’ve optimised it and the lens to do the best they can in the circumstances. Sometimes that’s a “noisy” picture if I use a small aperture for depth-of-field, and a fast shutter speed to stop the action. If that’s not acceptable, I swap to a different camera; a Sony A7S, say, with its lack of noise at nonsensically high ISOs.

I accept what I can’t change. But purposely emulating PROBLEMS and FAULTS? ..No, not my style, though it does seem to be others’..

Thank you for your carefully considered and constructed comment David. I must admit that I do personally feel empathy with what you say.

But there are folks who do embrace grain or its digital noise equivalent, and they are just as entitled to chase the "look" that they like.

Seems that it could be likened to the world of visual art. There are those who like realism (My wife doesn’t, she says that if you want realism then take a photo!). There are others who take it even further and like hyper-realism. Backing away to the other side, the Impressionists certainly weren’t realists. And if we really want to see grain in paintings then we need look no further than the Pointillism movement of the 1880s. Seurat and Signac sure put "grain" in their images.

If you really want to make your blood boil have a look at the youtube video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SXlRIQuYdzg

It’s only three minutes long. I really couldn’t help smiling amusedly as I watched it. Crazy stuff (well, that’s what I think).

I think that’s just silly, Wayne – but, as you say, it takes all sorts..

But maybe I’m daft, too: I like the old, early, blue-sensitive photos – like Atget’s – which rapidly go to white in the distance (where the scene was flooded with blue sky light), so I sometimes turn on the blue filter in the Olympus PEN-F (digital version) for a similar effect (..though the M9 seems to manage that, in black-&-white, without any filter).

This weekend I’m going to learn salt printing ..and the instructor’s asked us to send digital photos which he’ll turn into 10×8 film negs in order to print from them. Though that is a bit different ..my usual prints are full-colour Blurb books, but I really do like proper chemical blacks on real photo paper.

Perhaps I’m really just as weird as the pointillist photo adjusters, or the grain maniacs!

Oh; an extra response to Dave Seargeant up there: the Df’s a terrific SLR; quieter than most (all?) other Nikons, and with brilliant low-light capability!

Hi David, I am currently learning the idiosyncrasies of the Df, but it is an awesomely stunning bit of kit. I still dont truly understand the hate thrown at it by the reviewing fraternity. To me it is the best hybrid of the Nikon system, versus the Leica M system. A true alternative. Dave

A very nicely written piece.

I suspect that much of the difficulty with noise is that how it is perceived depends very much on the subject matter and the character of the noise. In subjects with a rough texture film grain ends is often perceived as sharpness rather than a degradation of resolution, while in smooth areas such as sky is obviously an artefact of the photographic process.

It also depends to some extent on the character of the noise. I have seen some RAW developer software that by default ramped up the noise reduction to a very high level – and then re-introduced noise deliberately as film grain. Without the latter the images looked very sterile and artificial. Perhaps it is just that after more than a century of film we are now very accustomed to seeing high frequency noise in images.

Hi Mark. Yes, the wheel turns full circle. After years of trying to sanitize noise out of images we find digital photography now offering it as an option, even if it is in a pursuit of a film grain look different from digital noise (altho there are some who suggest that digital noise done properly can produce a "film-like" feeling.

In addition to developer software, I must admit surprise seeing camera firmware sometimes now providing a menu option to "add grain" to digital images in camera. My Fuji X-Pro2 has it as a menu option, and I see that Panasonic have it on the new LX100 ii. There are likely many other cameras out there with it inside their complicated Menu options. Strange days indeed.

Nice article, Wayne. The digital era has brought a whole deal of discussion on digital artifacts and other factors which generally don’t bother real photographers. It is also a series passing fashions such as noise, of course, chromatic aberration, banding, Italian Flag and one whose name I cannot remember, but which involves a grid with rainbow effects. It is a long time since I saw much discussion on most of these as sensors and software have improved. In the film days we only discussed grain and sometimes we even treasured it. Reviewers and pixel peepers have a lot to answer for in respect of the present situation, of course, but some suspect that building in such defects is part of the business model of manufacturers who wish to persuade photographers to ‘upgrade’ their cameras at regular intervals to new models which eliminate such ‘faults’.

The really interesting thing in your article is the inclusion of two mysterious photos from Everest. Have I missed a story there? Is this a teaser?

William

Hello William. Thanks for your feedback. Yes, many of us do ‘upgrade’ more often and indeed own more cameras than we ever did in film days. I had Konicas and Minoltas then, at most only two at a time, and kept and used each of them for at least 10 years. Camera marketing has become a technical fashion industry ( I like your use of the word "fashion").

Regarding the Everest pics, no you haven’t missed a story, nor were they a teaser. It was a deliberate delve back into the past where digital noise was overpowering but I just had to catch the moment anyway. However, your comment has prompted to perhaps retrieve a few more of the high Himalaya images and put something together for Macfilos. The light in those isolated areas at the top of the world is so clear and clean, wonderful for photography.

Well worth pondering, Wayne. Basically agree with you. It’s not a question of noise/no noise or sharp/unsharp or indeed Low/high resolution but what the image taken as a whole communicates and whether the "artefacts" contribute to that or not. Are you down under or an I down under? – Depends which pole you are looking from!

Gday John.

You are quite correct. The image and the emotion it evokes is far more important than its technicals of the picture. And the photographer will often look and feel differently about his/her images compared with a casual or serious observer. To each their own.

And your question regarding who is actually down-under was actually touched upon just this week in a lighthearted email exchange with Michael, t’Editor of Macfilos. We wondered why cameras produce images the right way up in both northern and southern hemispheres, and whether in-camera firmware senses and corrects it according to hemispheric location ;-). Then got even more confused when we realized that the image at the sensor or film is upside down in the camera anyway ;-). Decided at that point to stop thinking or else we might get a headache!