Bobo was at the wheel of the Mahindra SUV as we headed north from Imphal. I rode shotgun, Hemant and Yai sat in the back seat. Our destination, Nagaland, site of one of Britain’s greatest battles, land of the Konyak headhunters, home to over twenty different tribes and sixty dialects. Surprisingly, it is also the foremost Baptist Christian state in the world.

The spread of Christianity in the Naga hills has, fortunately, put an end to headhunting. Less welcome, is the disappearance of other traditions such as the morungs (youth-training establishments), or the wearing traditional dress, or holding feasts of merit. However, the adoption of modern medicine and education has led to improved health and a better standard of living.

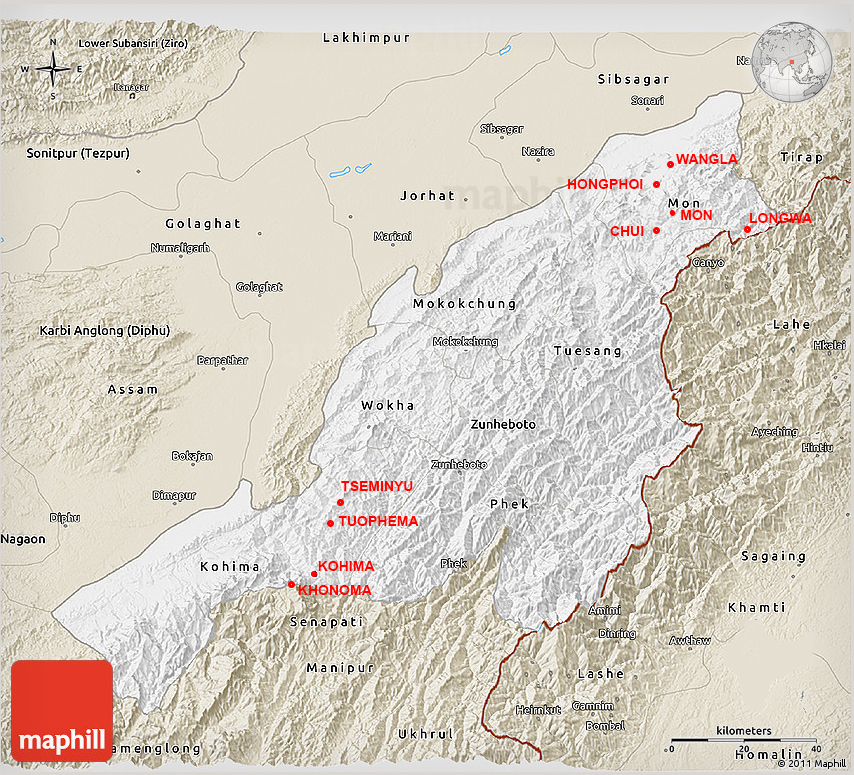

Back in 2014, I made two road trips through Nagaland. The first journey, the subject of this article, was in May and took me to Kohima, the capital of WW2 fame and site of a fantastic Commonwealth War Cemetery. Then to Khonoma, a village recognised as the green village of India and to Tseminyu and Tuophema, two pretty villages which I would love to visit again. Another trip later in November took me to Mon and the villages in the north.

Kohima: The Village on the Ridge

Well known for the Hornbill Festival held in December of every year, Kohima, the capital of Nagaland, was in 1944 the site of a bloody and tenacious battle during World War II — the Battle of Kohima, fought simultaneously with the Battle of Imphal.

Antony Brett-James recalls his first sight of Kohima in his book Ball of Fire The Fifth Indian Division in the Second World War:

You saw a village perched on the very peak of a sharp ridge, and built substantially of timber with red corrugated iron roofs. From afar the Nagas, with prodigious calf muscles, could be seen trotting up the steep paths, with their loads supported by a band across the brow. There, too, a pleasant smell of wood fires lingered on the evening air. Most welcome of all was a nip in the air as the light of day began to fail, with the promise of the luxury of a night slept in blankets, without the oppression of a mosquito net.”

Although no prodigious calf muscles were in sight as I surveyed the scene from my hotel balcony, the red corrugated iron roofs were still evident over a half century after the book was first published.

I touched upon some of the battle fronts in Kohima in a previous article, such as the famous tennis court battle, now the site of a Commonwealth WWII cemetery and memorial; the tank on the ridge and other reminders of the terrible siege of Kohima. I had, however, omitted to mention BK Sachü.

On a hill across from the centre of town, Khriezotuo Sachü, now in his late eighties, has set aside a room in his home in D Khel, Kohima Village, for his collection of WW2 memorabilia. My guide Mani and I paid him a visit.

A teacher by profession, Sachü’s collection includes hundreds of bomb casings, guns, grenades, ammunition boxes, helmets, photos, newspaper clippings, a typewriter and other assorted objects collected and labelled over a 35-year span.

We spent close to an hour poking about the various objects. At one time, I had a heavy, shiny black shell casing in my hands when the thought crossed my mind that I should ask whether it was defused. I remember I wasn’t completely reassured by the reply.

In an interview for the Nagaland Post in October 2019, Sachü said he could never forget the day they returned to their village after the war and how heartbroken they were to find everything destroyed. He recalled:

Our homes, our fields were all damaged, we had nothing to eat, it was so bad that we even had difficulty in finding the location of where our houses were.”

Still able to recollect events of the war in vivid detail, he hopes that through his collection and stories, future generations, including his four children and twelve grandchildren, will take an interest in learning and preserving their history.

Khonoma: A village to remember

When I made the trip to Khonoma, 20 km south-west of Kohima city, along with my guides from Imphal, Hemant and Yai, the road quickly made it to my list of the worst tracks I had experienced in the north-east. It was bare rock and gravel, pitted and potholed, with the top layers of tar completely stripped away. What should have taken an hour took twice that long. All that time I had the camera gripped in one hand while hanging on to the overhead handle with the other.

Khonoma is home to the Angami Nagas, an indigenous warrior tribe. It is mainly known for being India’s first Green Village when the village council implemented a ban on wildlife hunting and felling of forest trees.

Memories of the back-breaking journey soon faded at the sight of terraced paddy fields that stretched out in the valley below. Houses with corrugated roofs lined the two cobbled roads, free of litter, and vehicles, as they curved around the mountainsides. Two Saturdays a month the children of the village sweep the streets of any rubbish.

Naga traditions were passed on to each new generation of youths through morungs, or youth dormitories. Every village would have had a separate morung for girls and boys. Children entered it at an early age and were expected to live there while learning about Naga traditions, culture, music, dance, wood-carving and weaving.

These were essential centres for social interaction. Young males at a kichuki, a communal sleeping hall for males, acted as sentries, with weapons ready, at night to protect the village from enemy clans. After every clash, captured heads went first to the morung for the necessary rituals.

Through stories and folk tales of Angami heroes and heroines village elders would pass on their knowledge to the gathered children.

Malcolm Cairns noted in his doctoral thesis The Alder Managers: The Cultural Ecology of a Village in Nagaland, N.E. India:

According to comments from neighboring Angami villages, Khonoma’s men had a reputation for spending more time sitting around the house and talking than most. This may help to explain Khonoma’s high level of organization and capacity to involve itself in events far beyond its own borders. It also sheds light on why the agricultural work may have been left largely to the women.

Like the Huto Bokha Hou morung that we visited, today the morungs are mostly empty as children receive their education in public and private schools in the state.

But in their heyday, morungs would have been witness to contentious debates on crucial matters such as the ban on hunting.

In 1993, the Angamis were driving wildlife and fowl from the surrounding hills — including Blyth’s tragopan, deer, bear and mithun — to near extinction with their hunting. It was common practice to display hunting trophies outside one’s hut as a badge of wealth and stature.

The village elders came to realise if they were to preserve their rich biodiversity for the next generation they had to impose a ban on hunting and logging. It was a difficult task when the livelihoods of so many families depended on it.

Through long discussions and meetings the elders were able to get more villagers to join their cause, helped further when the Khonoma youth organisation joined hands with the village council. By 2002, a comprehensive ban was imposed on hunting and logging throughout the village. Bans on tobacco, plastic and packaged water soon followed.

In 2005, the government awarded Khonoma the tag of first “Green Village”.

We climbed a hill overlooking the valley. Kevichulie Meyase, whose family lives in Khonoma, narrated the story behind the memorial on the hill.

Years before Khonoma became a green village it was well known for it’s wily and brave resistance against the British who in the 19th century wanted to extend their sphere of influence from Kohima to the remote Naga hills in the north and south.

In his book, Among the Headhunters: An Extraordinary World War II Story of Survival in the Burmese Jungle, Robert Lyman writes:

Khonoma…rose against the new British threat to its hegemony in the hills. Political Officer G. H. Damant and thirty-six members of his escort were killed while visiting Khonoma on October 13, 1879, and Kohima was then subjected to a siege that lasted twelve days. The British garrison of some 180 men, women, and children was surrounded by 6,000 Naga warriors who wanted to sweep the British from their hills so that they could continue their traditional practices unimpeded by the white man’s law.

Gradually, one by one, villages gave up their practice of headhunting and bloodletting in return for British protection. In 1880 a peace treaty was signed between the British and Khonoma. To this day, the extraordinary exploits of the Naga warriors — how, with only their spears and daos they took on the rifle-armed British — are tales still narrated with pride by the village elders.

Tuophema and Tseminyu

Tuophema is about 45 km north of Kohima. I had called ahead about lunch. The lady was very apologetic that she couldn’t serve me chicken as requested at such short notice (I have some reservations about eating dog meat). She promised it for dinner though.

A typical Naga meal consists of rice, meat and boiled vegetables with chillies. Not much different to north Indian food. The difference is in the preparation. For example, in north Indian restaurants I can tell which part of the fowl is being served. Not so in the north-east. After all these trips to the north-east I am still unable to identify which piece of chicken is on my plate. So now I follow along and do like the locals do — that is, sprinkle salt over everything and enjoy the meal.

The Tourist Village where Mani and I were staying was a community initiative of the Angami tribe. Each of the twelve traditional thatched roof cottages was constructed by a different khel, or clan, without government support. The one I was in, No. 9, had been built by the Chazou Khel.

In appearance it looked like any of the other eleven; built of timber, bamboo and thatch with wood carvings of daos and bison heads. Inside was a small fireplace set in the mud floor, a table and chair. Farther inside, a bedroom, dark despite a window, and a view of the surrounding hills.

Tseminyu is predominantly inhabited by families of the Rengma tribe. Recently, in 2019, the town celebrated the 50th year of its founding. In the past, a new village site had to meet a couple of conditions for it to be considered suitable. It had to be easily defended against warring clans, and it had to have a prominent tree to hang the heads of adversaries. But all that’s a thing of the past.

On a walk around the pretty village we came upon Chuile (pronounced as chuey-ley) working on a shawl on her loom at home.

Today, traditional clothes are generally only worn on festive occasions. But in the past, there were strict rules that dictated the style and colour of cloth that a Rengma tribesman or woman could wear. From the clothes a tribesman wore one would have been able to tell whether he had taken a head in battle or he had offered a “feast of merit”.

Chuile had a few shawls that she had woven earlier to show us. One of them was a “zonyuphi”, a shawl with red and white stripes with spear motifs. In the past, this shawl would be worn by men who had sacrificed a cow or mithun. There being no such restriction or taboo to someone like me owning one now, it became the first of many that I would acquire.

Mon: Helsa has guests

Later the same year, I made a trip to north Nagaland, to a place called Mon. This was going to be my base camp for the next few days. From here, Mani and I would make day trips to Longwa, near the Myanmar border; Tang, Hongphoi, Wangla and Chui villages that are homes to the old headhunting tribes of Nagaland, the Konyaks.

Outside the main town of Mon, Helsa Resort had Veda FC, a Nagaland football club, visiting for the duration of my stay. Match day was coming up soon but for now the players were sleeping in late.

I was up early and had stepped out of my hut to take a look around on that first morning. Being November, there was a bit of a mist hanging in the air. That didn’t stop a young lad with his little sister in a sling on his back playing a round of marbles.

You know you’re going to have an interesting next few days when you have running hot & cold water. Literally. When I was there, Helsa Resort had a dubious connection to the electricity supply. After sunset, the lads from the football team would gather around a carrom board for a game under candlelight while I snapped away under starlight.

Longwa: A meeting and a passing

I had the “strange” honour of meeting the chief angh of Longwa in November, 2014. Strange, because he was very different from the picture of a chief angh I had in mind. He had on a T-shirt over a pair of shorts. And a tiger print hat topped with a feather and chin strap. That hardly matters now. This is from the Nagaland Post of 27 February, 2015:

Chief Angh of Longwa, Lt. Luhngam Ngowang breathed his last on February 25 after prolonged illness. He was 57. He was coronated (sic) at the age of 16 in 1974 and reigned over 33 villages, 30 villages in Myanmar and 3 in India. He had 7 wives of which 6 pre-decease (sic) him. He leaves behind a wife and 25 children. His funeral service took place today, which was attended by all 33 villages, Anghs from neighboring villages including from Arunachal and other dignitaries. He was buried after dusk as is the tradition of burying the Konyak Anghs.

When I met him a few months before his passing, he was already quite addicted to opium. He and his pals would sit around a fire in his longhouse smoking and chatting.

We sat on a couple of low stools after we had presented him with the gifts of almonds and tea that we carried with us. Soon he turned towards Mani and made a few gestures with his arms. After watching this a few times, I pressed Mani, who was obviously embarrassed by then, for a translation. After a bit of prodding, he said that the chief angh was asking me to buy him his next round of opium.

Opium was introduced to the Nagas by the British from across the border in Myanmar, in a bid to frustrate them from collecting heads, namely British ones. Many old warriors still wear a necklace of little bronze heads. Our chief angh being one of them. Now, one wouldn’t wish to annoy someone who collects heads, so of course, I was happy to buy him his next round.

We took a look around the chief’s longhouse. It was divided into sections, a front room for having the blokes over, and back rooms for sleeping and cooking. Interestingly, the international border between India and Myanmar runs right through his kitchen — it so happens that the chief angh of Longwa sleeps in India and dines in Myanmar.

In Longwa we met Tormba, a headhunter, sporting his trophies of brass heads on a beaded necklace round his neck. One brass head, I am led to believe, meant at least one human head. Two brass heads, meant a few more than two human heads. Over three brass heads meant we were heading into unknown territory.

Tormba’s face was marked by the fading traces of a distinctive tattoo, and through his earlobes he sported the horns of a deer. When I asked if I could photograph him, he put on a hat and coat. And that’s how I remember him, as the dapper headhunter from Longwa.

Matchday! LIVE

Match day rolls around. Veda FC have their jerseys drying in the sun and players are getting a trim by the local barber who has set up his chair in Helsa’s yard.

Football is popular across the north-east and at one point Nagaland had its own Premier League. Veda FC were crowned NPL champions in 2013 beating out Kohima Komets 42-40 in the point standings. They were hoping to repeat it this year as well.

The Nagaland Premier League has since been superseded by the I-League and the Indian Super League. According to the late Anjan Mitra, former secretary of the Kolkata-based club, Mohan Bagan:

20% to 25% of India’s professional football players come from the North East, a region that comprises roughly 8% of India’s land mass with about 3% of the country’s population. The states of Manipur, Mizoram and Meghalaya supply the majority of those players. Mohun Bagan’s under-18 football academy’s North East recruits are mostly from Manipur and Mizoram, with only a few from Nagaland.

Explaining the decline in Nagaland football in recent years, Dominic Sutnga, owner of Royal Wahingdoh FC from Shillong said in an interview in 2015:

Lack of sports infrastructure and the absence of a state league for a long time prevented players from Nagaland making a mark at the national level. There have been a few Naga players, but mostly from the hill districts of Manipur.

We returned in the evening from our excursion to the villages to see that a decent gathering of local supporters had turned out to watch the match. After taking a few shots of the game itself, I turned to face the rows of fans who were amused by the attention I gave them.

Christianity and the struggle for independence

After breakfast we set out for the villages of Wangla, Chui and Hongphoi.

Edward Winter Clark and his wife Mary, both from New York, established the first American Baptist mission in the Naga hills in 1876. At first not allowed to venture into the remote hills they, in the end, lived amongst the Ao tribe for 40 years learning their language and customs, gaining their trust and spreading the word of Christ and the virtues of living in harmony.

Before the Clarks arrived, and well after that too, Naga clans had been constantly feuding each other on some pretext or other. Along with British administration and the subsequent peace and order that it brought, feuds were settled by arbitration rather than beheadings and bloodletting.

Many traditional practices faded into obscurity with the spread of Christianity. For instance, the village shaman’s influence in times of sickness or death was severely tested when it became clear that modern medicine was more effective and cheaper in treating illness. Adopting Christianity was regarded as an effective route to access education, better health, and an improvement in living standards.

In Chui village, we come upon a mound of burial stones. Each stone representing a human skull that Baptist converts were required to bury when Chui converted to Christianity.

According to a National Geographic article published in 2015 on Nagaland:

Dancing and drum playing were banned, traditional relics and clothes burned—and skulls buried. The Baptists gave the disparate Naga tribes a common bond and language, English, but the loss of traditional culture also provoked an identity crisis that continues to this day.

But instead of finding peace after embracing Christianity, the Nagas would wage a long hard struggle for independence from the Indian state. For over a half century, Naga rebel groups have pushed for an independent nation that aimed to include all Nagas in India and Myanmar. It took 61 years for the Nagas to come to an agreement with the Indian government. We are yet to see how long this peace will last.

I had come to the end of my Nagaland trip. The next morning Mani and I were headed to Meghalaya. And its wonders.

Thank you Kevin. The headhunters are getting old and soon they’ll be gone. The late chief angh of Longwa died at a young age. Without being required to work for a living, and the borders being so porous I guess it was easy for the opium addiction to take root.

Thank you Farhiz for this very interesting and nicely illustrated article. I particularly like the way you got under the surface to illustrate and describe the realities of living there. You were fortunate to meet the head hunter as I assume he will soon pass on and your photo will become a record of the past. I felt a sadness for the chief who is reduced to asking for his next fix; so far from where he could be in his important role.

Wonderful Travelogue, Farhiz. I am from the southern part of the subcontinent and takes one through a myriad of thoughts on past, present and future.

Not sure how long these tribes would continue to be in their natural surroundings especially now that most lands are being given away to corporate’s for mining. The subcontinent already has one of the highest displaced tribes in the world with land being taken away forcefully from them.

During my residential years at school, I studied with persons from Mizoram, Assam and few from Nagaland, who gave a wonderful insight into their world. I still continue to be in touch with them and have longed to visit the ‘seven sisters’, but travels keep getting postponed due to various things that keep happening in North east ! May in the next couple of years I’ll visit Mizoram and the near by states.

But till then your travelogue will satisfy many of the travelers quest !

Thank you, Kannan. My guess is change will come rapidly to the villages as the internet, the cell phone and TV bring the world to their doorstep.

Thank you Dave. Yes, I had that thought too. I remember telling Mani after we’d left that the old chap will bring half the hill down if one of those was to blow.

One of those occasions where we photographers take the pictures and then run as fast as our feet will carry us away from the area. 🙂

What a wonderful article, with some wonderful images, and portraits.

I must confess the chap with the world war 2 arsenal sitting in his back shed wouldnt be a neighbour I would want in a hurry. That lot has the potential to perhaps reduce his house and several streets to rubble in the blink of an eye.

Dave

Thank you David. It was a pleasure being your guide this afternoon.

A superb travelogue Farhiz. And Happy Birthday!

Through your narrative and pictures you invite us to step into a different world. I like your environmental portraits showing people engaged in their crafts and activities. The soft light is particularly revealing of shapes and colours and activity.

Thank you for being my guide this afternoon.

David

Lovely writing and photos Farhiz. The saddest part is where the men are drinking and partaking of drugs. When cultural and social change happen, people often look for substitutes and breakdown of the old order ensues. It is good, though, to see the younger generation engaging in sport. In so many parts of the world societies find it difficult to make the cultural transformation which our ‘tomorrow’s world’ culture seems to demand. You have expressed all of these ideas and concepts very well in your writing and photos.

William

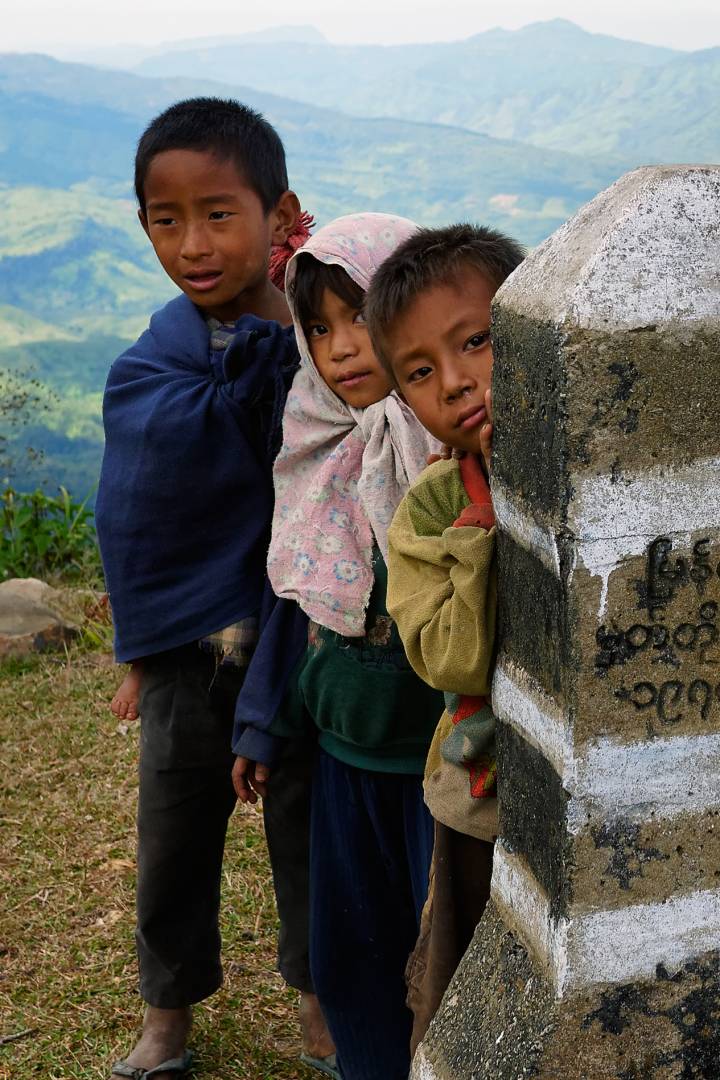

Thank you William—before the visit to Longwa I wasn’t aware of the opium problem. But apparently it has deeply affected the economy and the lives of the people. A big problem is the ease with which one can crossover to Myanmar from Nagaland. In the photo with the three kids there is a lone stone marker that marks the border between the two countries. Combine this ease with the local terrain, it becomes very difficult then to control the opium influx.

Thank you Farhiz for a wonderful article. The pictures and the way you document local life are really superb. The light in the last two images is simply amazing. Reading your articles India looks more like a continent than a country. Once again you made your 20mm lens shine. Thanks again for sharing with us

Thank you, Jean. Well in a way you are correct, India should really be viewed as a union of different cultures and languages. In the N-E the dialects can differ from village to village. That makes communication even for a good guide a daunting proposition (Bamin Baro my guide from Arunachal can speak five languages). Everyone relies on Hindi and English to communicate then.

I’m two days late, Happy Birthday Farhiz. The opium smoker made me think of the Ibis trilogy by Amitav Ghosh in which he spoke of the opium war between British India in the late 1830s and China. The first book starts in India.

Thank you Jean!

Farhiz, thanks for a a really interesting story and great photos. As Wayne says above we were due to go into Nagaland on the Myanmar side on a small riverboat up the Chetwynd River in just a few weeks time. Sadly due to Covid-19 your photos are the probably the closest we are ever going to get to the Nagas.

I do worry how communities such as those in your story in India and over the border in Myanmar are faring in the pandemic. Their health systems are very basic if not almost non existent and their communal life would make social distancing very difficult even if they were to try and practice it. I fear the worst. Let’s hope that I am wrong.

You are correct, John, though there are clinics and doctors in every small town, providing medical assistance in the villages, located in some very remote hills, is a challenge. But with the lockdown coming in swiftly in March this year the N-E has been spared the worst. My guide from Arunachal reports he and his family are well and since there are no travellers passing through he’s been busy in his fields.

The pictures and story were thoroughly enjoyable!

Thank you Bob, it’s been very enjoyable recollecting these encounters.

Thank you for this Farhiz. With Macfilos’ John Shingleton we were due to enter Nagaland from the Myanmar side in a few weeks from now. Unfortunately the Covid-19 virus has stopped those plans. So your images provide us with an idea of what we will miss.

I particularly like your people pics. There’s a lovely simple serenity in a number of them.

Wayne, I really like how you describe this. I feel the same way specially with the photo of the girl from Longwa.

The north-east has not been spared from the virus, though because of the remoteness and thinner population they haven’t been hit quite as hard as other regions. I am waiting like you and John for it to be safe to travel again.

AGain you have proven one could spend half a life time India and not scratch the surface on all the history it holds, and I agree would not like to meet Mr. Dapper in a dark alley. Looks like he comes from central casting.thank you for sharing your labors with us!

Thank you John—yes he does look like he could be cast in Mad Max XLV!

Lots of marvellous photos as far as I could judge. I only wish you could have found a way to let us blow them up to full-screen size.

That’s probably my fault. I will set it up

Now.

Ok done that now. You should be able to enlarge and also view a slide show.

Thanks so much, Mike. There is so much life and so much detail in these pictures that they deserve – and gain by – the larger format.

Thank you John and Mike. Yesterday I turned 60 and before I could get around to attending to your request I saw Mike had fixed it already.

Thank you for a very interesting read Farhiz. All of the images are very nice but the one that stand out for me is “Tormba the dapper headhunter”. He has a real “presence”about him.

Thank you David—the light inside the hut we were in played a big part.