The 9.45 Rajdhani Express pulled out of Colombo Fort on time. In the end it wasn’t a mad dash to get to the station, more like a light charge. We had arrived at Bandaranaike International at 10.30 the night before, checked into our hotel and, with scant appreciation of the sea-facing room, checked out early the next morning to catch the train to Nuwara Eliya.

The Express rattled through Maradana, Colombo’s other main station, and eastward to the countryside. After Rambukkana it caught up with the single track as it slowly made the climb towards Kandy. Rocked by the carriage’s rhythmic swaying on its springs, I was soon out like a light.

Nuwara Eliya — About a Scotsman, an Englishman and Tea

At Hatton, the train made a stop for passengers heading to Adam’s Peak, a place of pilgrimage revered by Buddhists, Hindus and Christians. Adam’s Peak is a mountain in central Sri Lanka. A rock formation near its summit, in the shape of a footprint, attracts Buddhists in the belief that it is the footprint of the Buddha. Hindus are likewise drawn there in their belief that it is the footprint of Lord Shiva. Christians believe it is where Adam first set foot on being exiled from the Garden of Eden. As importantly though, Hatton meant we were entering tea country.

The history of tea in Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then called, goes back a century and a half. India was still a British colony. Over in Ceylon, the British had by then taken over from the Dutch who had in turn taken over from the Portuguese.

In 1867, a chap from Scotland by the name of James Taylor planted some tea seeds, brought over from India, on a small twenty acre patch of hillside on a coffee estate in nearby Kandy. And just as well, for soon a terrible blight destroyed the coffee plants. The distraught planters turned to tea.

Then, sometime in the 1870s, a fellow called William Flowerdew, from Norwich, England, bid for a 250-acre plot at an auction and named the estate Hethersett, situated in Nuwara Eliya (noor・eliya in Sinhalese).

Several times over the years the estate switched hands. In 1897 it merged with the Nuwara Eliya Tea Estates Company, registered in London, a relationship that lasted 75 years.

“Tea from the factory began its journey to market in tea chests carried by bullock carts down the rough tracks to the railway station at Kandapola. The narrow-gauge line was opened in 1903 from Ragalla via Kandapola to Nuwara Eliya and Nanu Oya. At Nanu Oya, the tea chests were transferred to the main, broad-gauge line, and sent for delivery to the Colombo godowns. After the auction, the tea chests went by steamship to England or Australia.” —The History of the Nuwara Eliya Tea Estates Company 1870s – 1972 by Ian Gardner.

A factory was built sometime in the mid-1930s on a flattened hilltop on the estate. Through the 1940s and ‘60s, it produced consistently top quality Ceylon tea for export under efficient and competent managers.

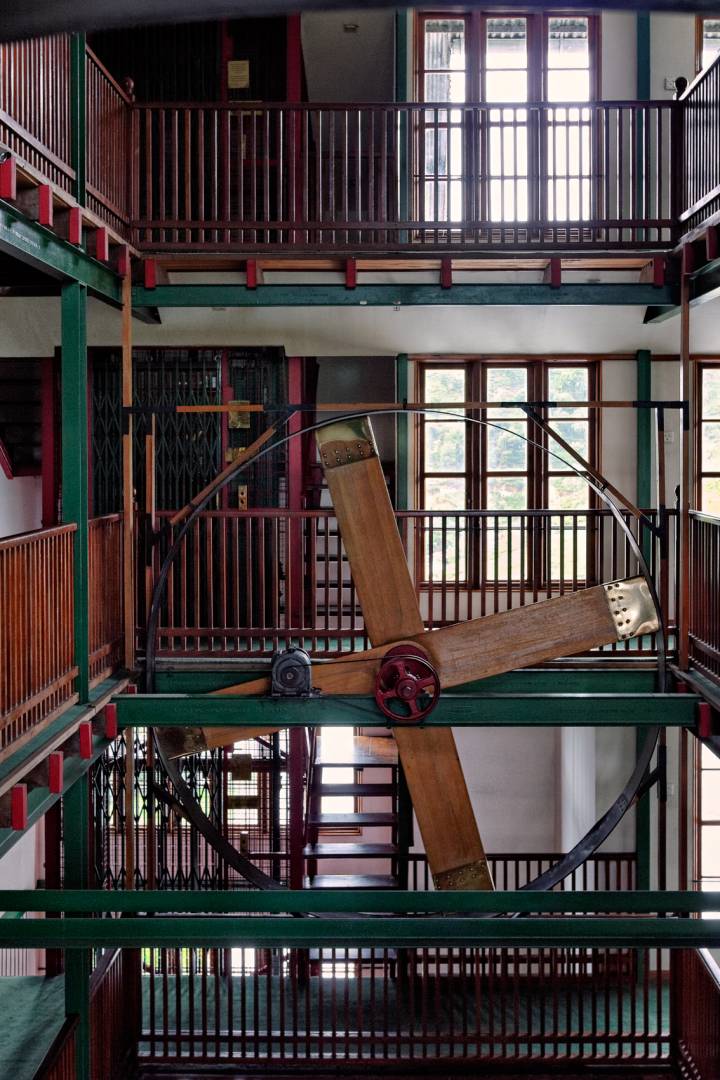

By the late-1960s, however, the estate was past its heyday. It was no longer economically viable to keep the factory running. Its oil fired engine, the fly-wheels and pulley systems that operated huge fans for withering tea leaves were sorely out of date.

It fell on the last estate manager, J. M. E. Waring, to close the doors of the factory for the last time. For twenty years it lay as “a silent monument to the great days of Pure Ceylon Tea.”

Second Life

The tea factory’s chance at a second life can be attributed to a director of Aitken-Spence, the new owners of the estates, who chanced upon the structure in 1992 on a tour around their new properties. Almost instantly, an idea took root.

G. C. Wickremasinghe, together with architect Nihal Bodhinayake, set about transforming the old tea factory into a hotel. The idea was to retain as much character and as many features of the original tea factory and incorporate them into the new design of the hotel.

The building preserves its original facade — the aluminium siding and windows — and the interior has been repurposed to suit its new function while keeping some of the old machinery and equipment. The old drier room of the tea factory is now the reception area, the green leaf withering lofts are the guest bedrooms, the sifting room is the restaurant. In addition, the engine that once powered the factory, the fans and pulleys, and weighing scales have been retained and preserved.

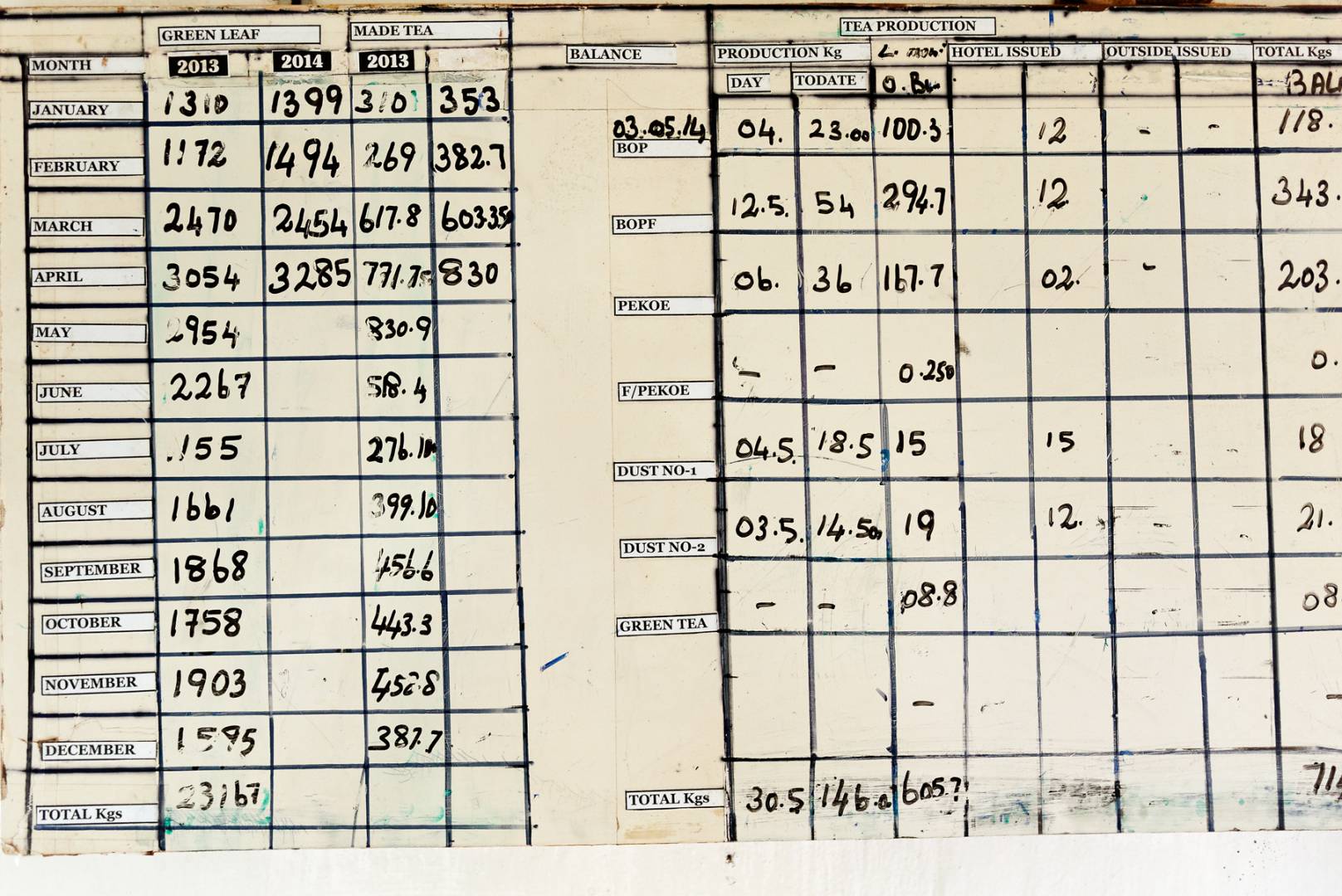

Another of Wickremasinghe’s ideas was to install a miniature tea factory on the site of the teamaker’s quarters. It is open to guests of the hotel to browse about and try their hand at plucking some leaves themselves.

Wickremasinghe managed to wrangle a miniature drier from the Tea Research Institute and other machinery and odds and ends, necessary for tea production, from second-hand shops in Kandy. The guests then could be presented with a bag of tea ostensibly with their plucked leaves after it was processed at the miniature factory as a memento on departure.

Galle — Life returns

After a train journey back to Colombo followed by a beachside stopover in Bentota, we took the scenic coastal road to Galle, located on Sri Lanka’s southwestern tip.

Ten years ago Galle had been devastated in the wake of the Boxing Day Tsunami. Though far away from the epicentre near Sumatra, waves as high as a two storey building smashed inland levelling everything in its path — buildings, homes, the stadium, schools, cars, boats, trees, and people. After the waters abated, and the scale of the disaster became evident to Sri Lankans and the world, the international community responded with immediate relief.

Some survivors though didn’t wait for aid to reach them. “‘Most of what I have achieved today is from our own efforts and hard work,’ says L. W. Chandrakanthi, a tsunami survivor, explaining that she did not depend on donor funding or wait for funds to get to her, or go to village heads seeking funds.” —From The World Bank, ‘Lessons Learned from Sri Lanka’s Tsunami Reconstruction’.

For a few others, aid from the government in the initial months led to a culture of dependency. In certain camps fishermen refused to return to the sea, quite content to spend their days idling.

Our hotel lay a few metres from the water’s edge. When the waves crashed inland that fateful day, staff and guests were moved to higher floors. But today the sea rippled with a gentle breeze.

The Portuguese, the Dutch and the British (again)

I made arrangements with a tuk-tuk driver to fetch me from the hotel early one morning and take me to Galle Fort. Built on a headland that juts out into the sea, the structure was initially fortified by the Portuguese in the late 16th century.

Galle Fort is recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage site for displaying a unique commentary on European and Asian architecture and tradition.

The Portuguese first made landfall here in 1505. After an alliance with the king of that time, by 1541 they had begun work on a fort and Franciscan chapel. A later move to Colombo, in a bid to increase their influence, was short-lived. Attacked by the Sitawaka king, Rajasinha I, they were compelled to return, in 1588, to Galle.

By 1640, the fort fell into Dutch hands. And it was to remain under the Dutch until the early 18th century. They used the intervening time to strengthen their defences and build a number of structures that included a Commander’s residence, a gun house and arsenal. For the residents, the Dutch built a Protestant church, a hospital, living quarters, and workshops.

In 1796, the Dutch fort fell for a second time into the hands of the British. A round of new construction soon followed. The moat was sealed, the All Saints Anglican church was built in 1871, a clock tower was erected in 1882 to commemorate the golden jubilee of Queen Victoria, and a mosque was built in 1904.

Comeback Kid

On reaching the fort gates, I let the weight of its history sit lightly on my shoulders. Of more interest to me on that morning was to see how life had returned to the old fort after the events of 2004.

C. W. W. Kannangara school had been destroyed in the Boxing Day tsunami. The force of the waves swept away classrooms in the school located just thirty metres from the sea. Nor were the children’s homes spared. According to a March 2005 UNICEF report, “Of the 336 children attending Kannangara school, 89 lost their homes in the tsunami.”

With contributions from all over the world, it was the first school to rebuild and reopen its classrooms. Headmaster Mampitiya Dharmabandhu in a December 2018 interview to the Scottish Daily Mail recalls, “There was only debris left, the school had been broken by the waves and all around was heartbreak, but out of disaster it has been reborn better and stronger.”

A Hotel with a heart

Christopher Ong left a career in investment banking with Credit Suisse at 40 to follow his passion of restoring old buildings. Born in Penang, Malaysia and educated in Australia, Ong found that Sri Lanka reminded him of home. He was looking for a place, he says, that nobody wanted. He found it in an abandoned Portuguese-Dutch residence built in 1700, with walls made of rock and coral and clay.

Over the years, it had functioned as a post office, a bakery, an RAF officers’ mess during World War 2, and even a pitch for the fort’s young cricketers. On the night the tsunami reached its doorsteps — the old building had already been painstakingly restored and converted into the Galle Fort Hotel — Ong was having his dinner. Remembering that night in an interview years later he says, “We were at the high point inside the fort. Inside the fort, it looked like Venice, the roads became canals.” Barely a year old, the hotel opened its doors to all who wanted to seek refuge from the onrushing waters.

But, this particular morning, I refrained from puttering up to its front doors in my tuk-tuk and going inside, instead being content to wander about the streets outside.

A Fort with a Community

Early morning is probably the best time to walk the quiet lanes of the Dutch colonial-era fort. Magistrate’s Court, on Leynbaan Street, just off Queen’s Street, is a popular place for wedding shoots. The ground was still wet from the night showers but that didn’t deter the newly weds or their bridesmaids from turning out in all their finery.

By ten in the morning, the quiet and intimateness would give way to a crowd gathered inside and outside the court as the chief magistrate of Galle proceeded to hear the day’s business.

Religious institutions in Galle Fort, like the mosque, exert a strong positive influence on the Muslim male population. News of the community, wellbeing of its members, religious and cultural programmes for women and children are discussed in an effort to bring the community together and strengthen inter-community relationships between the Sinhalese and Muslims. Special attention is paid to guiding young children.

As a long-time resident Fathima Hanim Siyoothy, who learnt to swim after the tsunami at the age of 54, once declared, “I am very attached to the Fort. We are a very closely knit community. We don’t think of religion, race or creed.”

Though the population in Galle Fort has declined in the past few years to under a thousand persons, another long-time resident, Prasanna Abeywickrama, whose father bought an old Dutch house in 1979, says “I love the Fort. I enjoy knowing so many people by name. We are like one family.”

With the gentrification and the influx of tourists that followed the heritage listing, many local residents have started small scale businesses, running guest houses, renting out rooms to day trippers, arts and craft shops, cafes and restaurants.

The new economic prosperity is slowly changing the fabric and identity of the fort community. The increasing number of expatriates buying town houses in Galle Fort as a second home or a holiday home and leaving them shut for long periods or rented out to non-locals as guest houses, has left physical gaps in the neighbourhoods of the living communities.

In addition, the features that are so distinctive of old Dutch colonial houses, the verandahs, are being converted into small shops which essentially changes the character of the streets.

The stretch of green open space along the fort walls has been for a long time a favourite place for residents to gather in the evening. It serves as an informal meeting spot for friends and families walking and sitting on the ramparts.

This is dampened somewhat during tourist season when the locals are out-numbered by the tourists. The local community finds itself uncertain as to what to do to save their sense of place dependent as they are on the economic activity that tourism brings to Galle Fort.

The 2nd Volunteer Battalion of the Gemunu Watch has its base in Galle Fort. It can trace its beginnings to 1883, when a volunteer force detachment of the British Royal Infantry Company was deployed in Galle. This morning they have taken over a length of Rampart Street for their morning drill.

Stick No Bills™ is a gallery run by Meg and Philip James Baber from an old Dutch colonial merchant’s town house on Church Street in Galle Fort specialising in vintage travel and film posters based on the island’s history and culture.

Later at Unawatuna, a beach town near Galle Fort, I made my version of Samarasinha’s iconic poster.

The cobbled streets in Galle Fort still retain their original colonial era names. I walked down Pedlar Street or Moorse Kramerstraat named after the profession of the Muslim retailers who inhabited the area (see map); then along Church Street which during the Dutch period was named Kerkstraat after a church that was pulled down in the 17th century; onto Lighthouse Street or Zeeburgstraat and Leyn Baan Street or Leyenbahnstraat.

These lanes and the structures and open spaces on them are the tangible aspects of the Fort community. Just as important are the intangible aspects; the values and traditions that hold a community together. As residents are finding out they’ll need to do a fine balancing act between economic prosperity and traditional values if they are to have their cake and eat it too.

It’d be real nice to see what the places looked like back then. Maybe there’s a story in there somewhere?

The timing of your article was perfect as I had just finished scanning my negatives from Sri Lanka in 1987. I spent eight weeks there including two weeks based at Unawatuna which was just magical. I also have photos of tea pickers in the hills near Nuwara Eliya. Unfortunately while I was there the troubles escalated quite dramatically so we avoided Columbo all together. But such a beautiful country and people.

Thank you Farhiz for your evocative images and article which reminded me that I hope to pay another visit to Sri Lanka once we are safe to travel again. Our previous train journey to the tea estates and stay in one of the bungalows was a wonderful experience which I would happily repeat not only for the tremendous views but also to appreciate again the work of those who surveyed and built the track back in the nineteenth century. Equally amazing was the scale of some of their ancient sites, such as Polonnaruwa, the existence of which I am ashamed to say I was previously unaware. Unimagineable however must have been the sight of the tsunami bearing down on Galle and about to snuff out 30,000 + souls.

Thank you Richard. I believe a lot of work has gone into improving the early warning systems and procedures. So hopefully they will be better prepared should an unfortunate event like that ever occur in the future.

A very enjoyable article Farhiz, thanks. I particularly liked the interiors of the hotel and hope to visit there one day. Friends vacationed on a tea estate and enjoyed the walks through the plantations. I echo Wayne’s comment on your use of perspective and it was good to have the map of the fort, very helpful.

Thank you Kevin. I felt that the map would help in placing the various locales of Galle Fort in the reader’s mind. If ever you do stay at the Heritance hotel remember to carry a wind cheater.

Another epic journey and filled with wonderful images too. I believe I learnt more about Sri Lanka here than anywhere else in recent years.

I wonderful way read for my Saturday while sitting on Brighton seafront.

I will certainly look forward to your next article. Farhiz

Thank you Dave. Writing these articles for Macfilos is actually a great way for me to reconnect with these trips. Am glad you enjoyed them too.

Thank you William. Thankfully the civil war had ended by the time of our visit. Conflict has turned so many beautiful spots in our world into dangerous destinations. Hope you can make that trip to Sri Lanka one day soon.

Wonderful article and photos, Farhiz. During our time in Doha we became friendly with a lot of Sri Lankan people. My wife became particularly friendly with a Sri Lankan woman whose husband, an Englishman, worked in Doha. We were invited to an event to celebrate Sri Lanka National Day and we were made to feel wonderfully welcome even though we had no connection with Sri Lanka. There was, of course, plenty of tea, the singing was wonderful and stirring and the ‘Lanka Lion’ was to be seen everywhere. We talked about visiting Sri Lanka as it would have been a reasonable journey from Doha, but the Tamil Tigers were active at that time which would have made any trip unsafe. Maybe we might get there some day when Covid has passed.

William

Others have said it already: this is a marvelous tapestry of words and pictures. Thank you – and for the encouragement to do more single focal length photography instead of zooming around. Only one criticism: surely your last sentence should read “if they are to have their tea and drink it too” ? !

Hahaha – it sure should be! Thank you John.

Quite enjoyable to open Macfilos and be presented with armchair travel from you Farhiz, especially in these days of confinement to our home bases.

Your use of perspective in some of the people pics makes them interesting images for me – the waving arm on the train, the look down onto the beach, and looking up to the family walking along the rampart walls.

Thank you Wayne. That arm belongs to my wife. I was sitting in the seat behind her when she suddenly decided to give the passing hills a wave.

Thank you for the images. But thank you also for your historical journey here through the past 500 years.

This is a part of the world I did not see so far but would love to in my near future.

The little Panasonic GF 1 is a remarkable little system camera; I own two of them.

None with an original lens as I keep my Fuji X system free from anything original since I am not and never was in anything AF.

Would you mind to disclose the 20mm lens to us?

Best regards

Harry

Thank you Harry. The lens is a Lumix 1.7/20mm. Bought it together with the GF1. It’s never come off the camera. I manually focus in conjunction with a Panasonic Live View external finder.

Thank you, what a nice trip! Is that lighthouse functional, and was that beach photo taken from there? Glad to see you write that there is good economic news for the people. I am already looking forward to your next journey with your Panasonic.

Thanks John. I think it is still functional, so maybe I missed a chance to go up. The beach photo is taken from a spot near the lighthouse.

A wonderful set of images and a truly well documented history of the former colony Farhiz.

It brought fond memories of my visit a few years back. While visiting the tea lands I was appaled by the tea pickers living conditions (Mackay’s tea plantation not far from Ella and Haputale). Remnants and scar from the civil war were still visible as well. The greens of your third image of tea plantations are truly amazing. You’ve made your small Panasonic shine. The output you get from that small pancake lens is just beautiful. Thanks for sharing and stay safe.

Thank you Jean. The greens in that photo were helped in no small part by the beautiful countryside and its rolling hills.

Thank you Farhiz, nice story and very good photos!

Thank you Andrea. Glad you enjoyed it.