Tawang lay at the end of a day-and-a-half’s journey by road. Crossing the Brahmaputra from Assam, we were on the third day of my first trip to Arunachal Pradesh in India’s north-east.

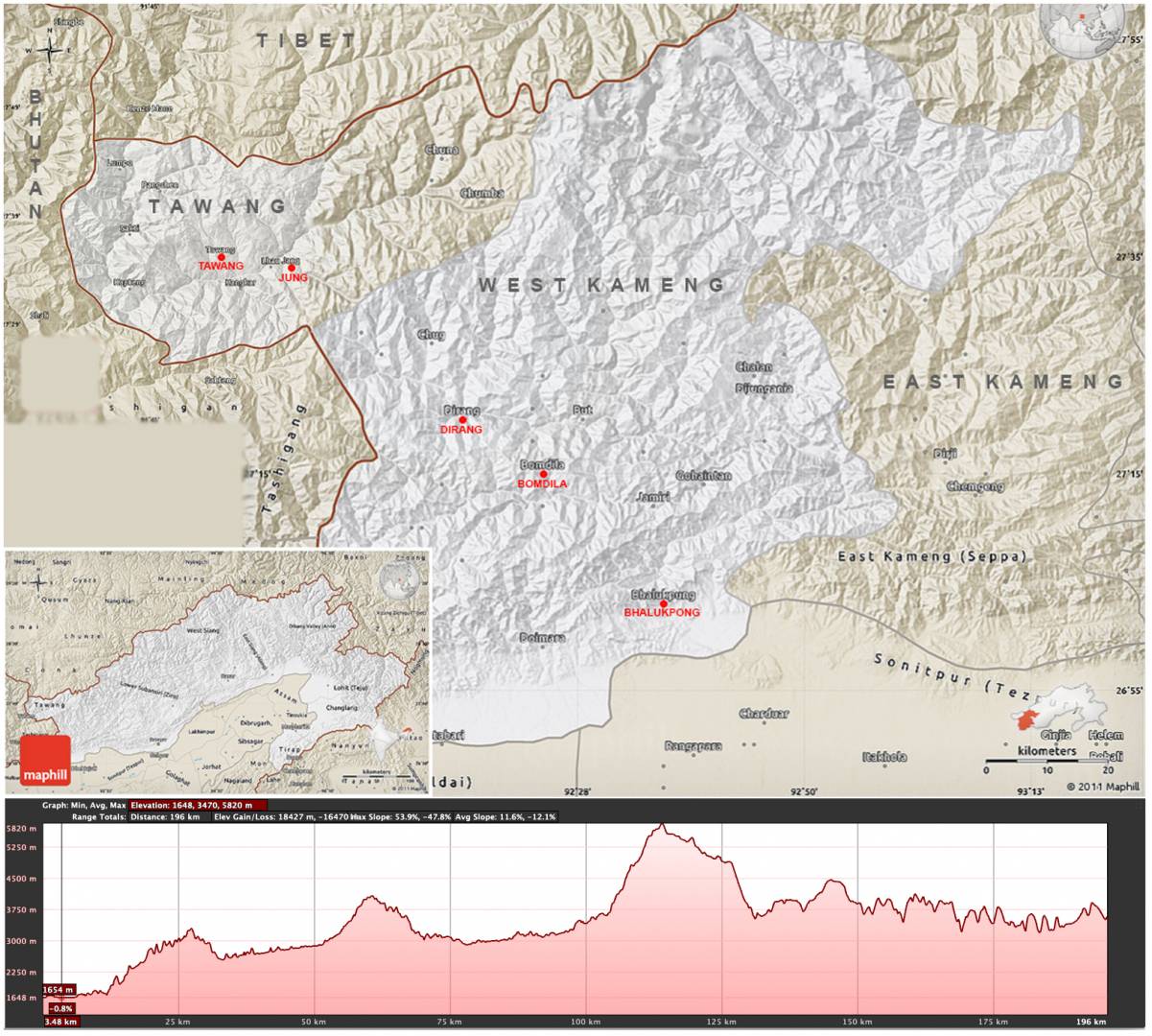

To reach Tawang, the NH 229 winds through the southern reaches of the eastern Himalayas. It starts its ascent from Bhalukpong, the first town on the route, climbs past Bomdila at 7,900 ft, then rises to Se La at 13,700 ft before finally, after twisting and turning for 273 kilometres, descends upon the monastery town of Tawang at just over 10,000 ft.

Bhalukpong—first port of call

We crossed the inner line1 at Bhalukpong and by noon were in the Sessa Orchid Sanctuary. Orchids bloom through the year in Arunachal—it’s wet and humid climate, dense, moss-laden forests, deep gorges and hills combining to make it an ideal habitat. An orchidarium in the small town of Tipi carries out research and conservation.

Bamin Baro, my guide from Arunachal, led the way inside.

The centre’s main attraction is its glass greenhouse where orchids of all shapes and colour are on display in pots and from hanging baskets. Someone working towards a degree in botany would feel right at home. I, however, needed to take pictures of the labels as a memory aid.

Outside the greenhouse, the orchidarium had several areas for cultivation of the rarer blue and red orchids, pineapple orchids and others. In one fenced and shaded spot on the grounds was a pitcher plant, at another the bamboo orchid was being cultivated.

By the time we got back on the road the weather had begun to close in. I learnt that this stretch from Sessa is perennially blanketed under clouds, shrouding the hills in a magical mist. The slow and cautious driving though—not a bad thing really when you can’t see the bonnet of your car—gave me the opportunity for taking a picture or two.

How a village got its name

By two in the afternoon, hungry and wanting our lunch, Nag Mandir seemed a convenient spot to break journey. How the little village got its unusual name, which translated means snake temple, I can’t say for sure.

The story goes that years ago one of the road construction crew members working on the stretch passing through the village killed a snake as it was drinking water by the road. That act brought bad luck to the village. The snake’s mate sought revenge.

Landslides and bad weather put a stop to the work on the road. Villagers and workers suffered snake bites. It all got a bit too much.

In an attempt to placate the angry gods, a temple to the snake gods was proposed and built. The gods being thus appeased, work continued on the road to Tawang. And that’s how the village where we stopped got its name.

What’s up, BRO?

The Border Roads Organisation, more popularly referred to by their abbreviation, BRO, has been busy since its formation in 1960 in developing, building and maintaining the roads, tunnels and bridges along India’s borders with its neighbours, specially in the remote regions of the north-east.

While one is impressed by the skills of BRO’s engineering corps in building roads in the rugged conditions typical of high altitudes like on the road to Tawang, it’s their often humorous road signs that have caught the eye of many travellers.

Despite BRO’s reminders along the side of the road, “Don’t gossip, let him drive”, it’s difficult not to be distracted when a sign says, “Check your nerves, On my curves”, or something like, “It is better to be Mr Late, than being late Mr”. They offer sound advice too. For instance, “Let your insurance policy mature before you”, always a good thing one would imagine. However we didn’t come across that one this time. Heck, as another road sign paraphrased 007, “You live only once”.

Over the days we came to regard these signs as constant travelling companions with a sense of humour.

Dirang Dzong – a fortified village

We drove along the road for another two-and-a-half hours from Nag Mandir. Bypassing Bomdila for now (we would stop for the night there on the way back), we headed on to our first night stop in Dirang.

We had booked to stay at the Pemaling Hotel with promises of grand views of the Dirang valley. But before that we made a quick stop in Dirang Dzong, a Monpa village.

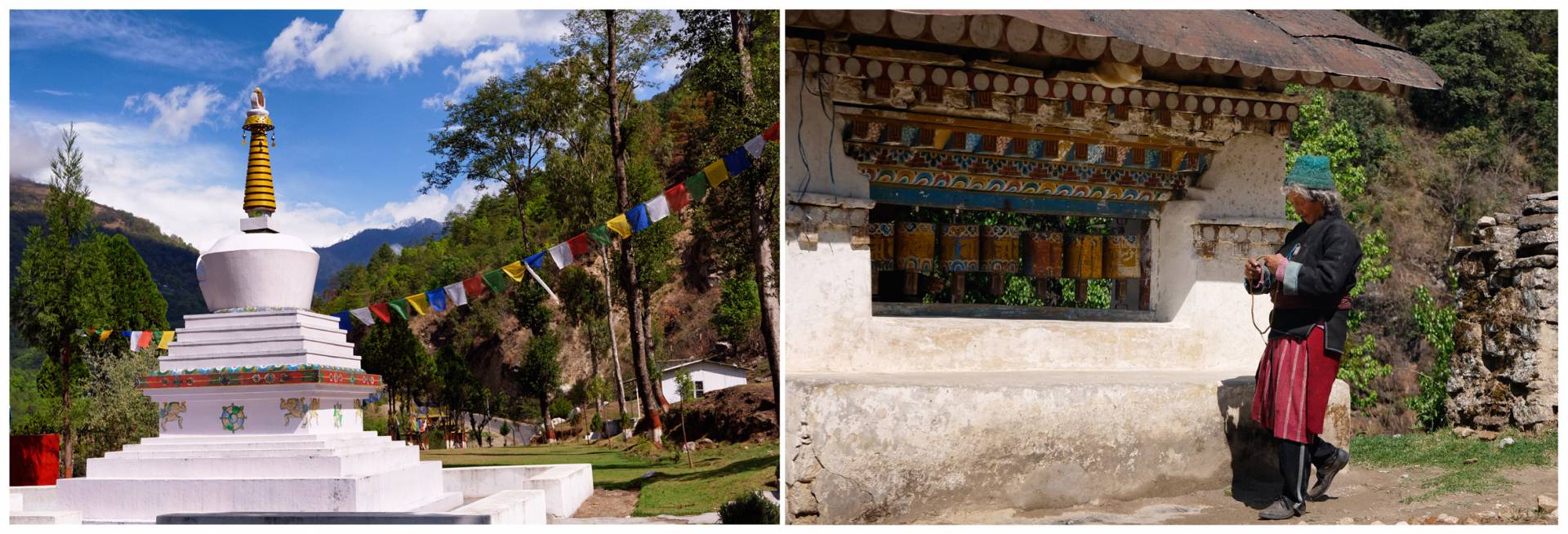

Dirang Dzong had briefly been a Divisional HQ during the Sino-Indian war in 1962. Before that, it perhaps served as a fortified prison of sorts. Perched on top of a hill is the Khastung gompa dating from the 16th century.

At the entrance to the village, along a flight of stone steps, in a niche in the stone wall, is a prayer wheel, its roll of leather scriptures worn and torn. According to Tibetan Buddhist tradition, spinning a prayer wheel, called a mane in Tibetan, with mantras inscribed on them serves the same purpose as oral recitation of the prayers.

A person will gently spin the wheel clockwise in the same direction the mantras are written, while simultaneously chanting the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. The belief is that the more mantras written on a prayer wheel, the greater is its power.

This particular one appears to have been inspected by a curious devotee in the past and I believe passed muster.

The traditional Monpa houses here had thick walls built of flat stone, blackened by rain, stacked several storeys high. Corrugated iron sheets served as roofing material, giving better protection against the rains than woven bamboo. Houses typically would have a basement where the livestock was kept. Living and sleeping rooms would be on the first or ground floor. A prayer room would occupy a higher floor.

From a clearing in the middle of the group of houses rose a stone tower-like structure, its windows shuttered, a notched log for stairs propped up against the wall. It takes a particular sideways stance and good balance to get up or down those things. So, if one is in a hurry, my advice to them would be: Don’t be. On a later trip I would come across similar stairs at La Maison de Ananda on Majuli and by then I knew better than to argue with them.

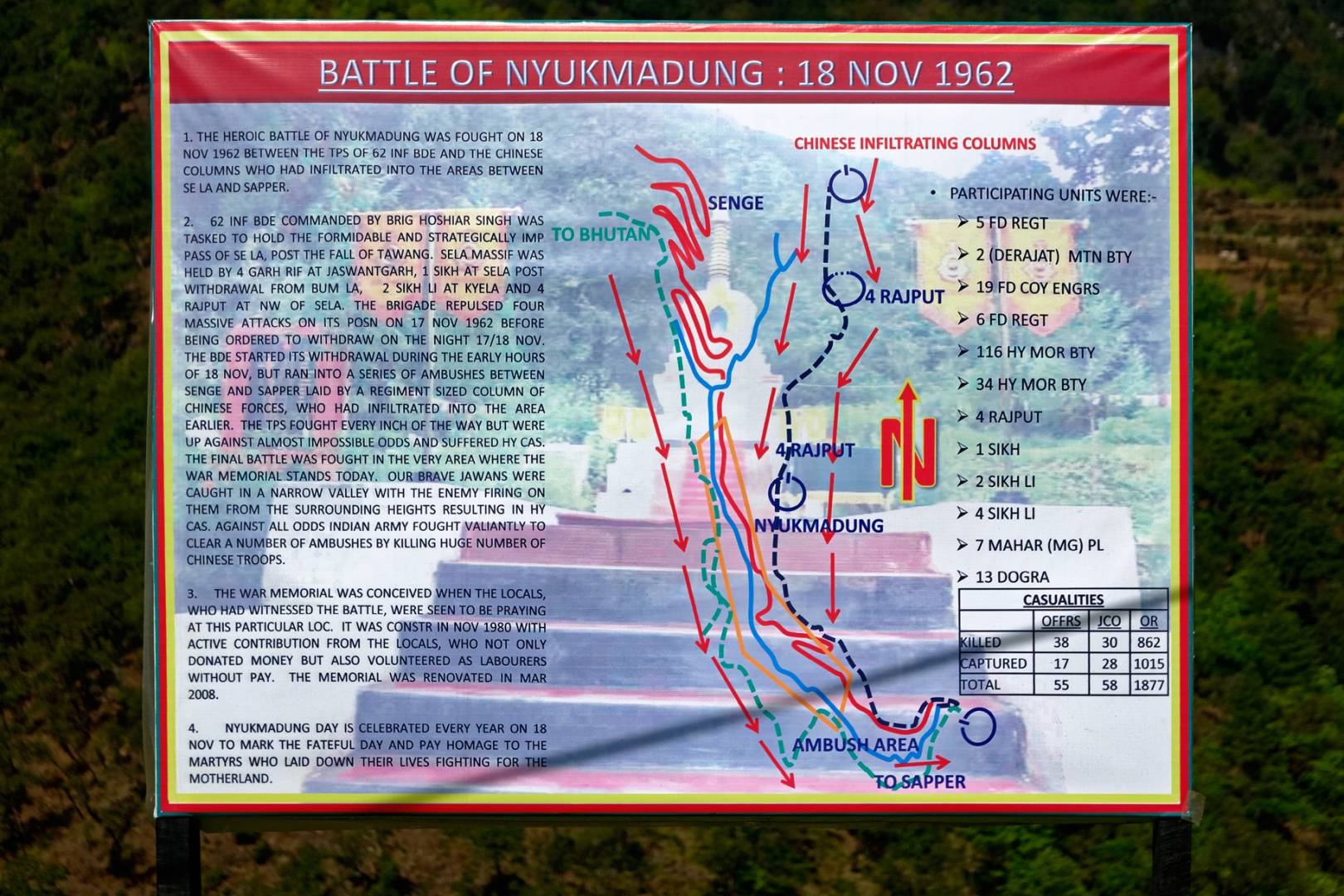

The Battle of Nyukmadong

On November 18, 1962, 62 Infantry Brigade and Chinese troops clashed in Nyukmadong, a small village in the Dirang area. Indian troops were withdrawing from Se La, a pass through the high ranges before Tawang. The Chinese had made incursions from Se La when the battle ensued.

After the ambush, the Chinese laid out the bodies of the Indian soldiers at this spot. According to a report in The Hindu, “Lobsang, a gaon bura2 and an office bearer at Dirang headquarters, recalls seeing hundreds of bodies in Nyukmadong. ‘It was a terrible sight. After the Chinese left, following the unilateral ceasefire, the villagers got together and cremated them.’ ”

Se La—pass in peace

Two hours out of Dirang, we navigated the hairpins up to Se La. The La, which means pass in Tibetan, connects Tawang to the rest of Arunachal. At an altitude of 13,700 ft, the snowbound pass is closed three months of the year.

The road was a mix of mud and slush and gravel. We weaved around rocks and small boulders that had tumbled down on to our path in a previous downpour.

On that day, there was a light snowfall and just enough cloud cover to lend the place atmosphere but not so much to ruin its views. Still, weather conditions could change rapidly. When we reached the gates to Tawang district there was time, however, for tea in the lone tea shack and to take a photograph of the resident husky.

But behind these majestic views lay a sombre truth. It was the fall of Se La in the 1962 war which allowed the Chinese to seize Bomdila and Dirang Dzong after they captured Tawang in the early days of the conflict. The Chinese in ‘A History of the Counter Attack War in Self Defence’ described the deployment as “Copper head, tail made of tin and a soft underbelly.” Se La was the “copper head” to be smashed.

In under an hour I would learn more of the heroics and sacrifice of the men who fought in the war.

Jaswantgarh—heroic tales from the war

On November 17, 1962, Rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat of 4 Garhwal Rifles, along with Lance Naik Trilok Singh Negi and Rifleman Gopal Singh Gusain, were tasked with the mission to neutralise the enemy MMG that was threatening their post from a higher vantage point in the area of the Nuranang valley.

LN Negi provided cover with his Sten gun while RFN Rawat and RFN Gusain lobbed grenades into the enemy bunkers. They managed to stall the enemy advance for 72 hours before falling in battle.

For his bravery, RFN Jaswant Singh Rawat received India’s highest gallantry award posthumously, the Mahavir Chakra.

But there is another tale of Jaswant Singh’s heroism. When he was tasked to silence the enemy MMG, two Monpa girls came to aid him in his mission. They were the sisters, Sela and Nura Nang.

During the 72 hour standoff while Jaswant hurled grenades at the Chinese in one bunker after another that fooled them into believing they were facing a large contingent of men, the sisters brought him food and ammunition.

When the Chinese troops realised that it was one man keeping them at bay they attacked with greater force. When Jaswant was killed in the assault, Sela, who was in love with him, threw herself off a cliff. Nura met her fate at the hands of her Chinese captors.

But wait, there is more to the story of Jaswantgarh.

The memorial erected in his name also enshrines his belongings; his Army uniform, cap, watch and belt. A lamp is forever lit in front of his portrait. His caretakers, drawn from 19 Garhwal Corps, serve him morning tea, breakfast and dinner. They make his bed, polish his shoes and leave his mail for him to see. For them he lives.

Nuranang Falls—a waterfall named after a Monpa girl

A couple of kilometres farther along, Baro and I clambered down from the edge of the road to the base of Nuranang waterfall near the village of Jung. In hindsight, this was probably a bad decision on my part.

The waterfall thundered down from its hundred metre height into the Tawang river. A small hydel power plant near the riverbed generated electricity for the villages in the area.

Besides one other group, we were the only people there that day. Unless the spirit of a young Monpa girl was also present.

Climbing the long flight of stairs to our car left no doubt in my mind about the peak physical condition I was in. The fact that Nuranang was at 6,000 ft didn’t help matters.

Tawang—home to the ‘celestial paradise on a clear night’

At about five in the evening we finally reached Tawang, home of the Tawang Gompa, the second largest Buddhist monastery in the world. The Dolma Khangsar hotel welcomed us with open arms. But my heart did sink a bit when I found my room was up on the third floor. In this rarefied air that was 30 ft more than I wanted to climb. The night was long. I couldn’t wait for tomorrow to come.

This article was originally conceived as a single topic covering the road journey to Tawang as well as the place. There was so much to describe on the journey there itself that I decided it called for a separate feature. Next time I’ll cover Tawang and Zemithang.

All photographs were taken with a Panasonic LX100 and Leica DC Vario-Summilux 24-75mm f/1.7-2.8 fixed lens.

- Arunachal requires all visitors to carry a permit to travel within the state called an Inner Line Permit or in the case of foreigners a Restricted Area Permit. ↩

- According to the Handbook for Gaon-Buras & Panchayati Raj Leaders by Prashant S Lokhande

“The Gaon Buras are the most important village level functionary. They are responsible for all the developmental and law and order related duties in the village.” ↩

Another wonderful photo-logue of an area I suspect few of us will ever visit. You must have a lot more courage than I!

Your stories and photos kept me engaged to the end (which always comes too soon!)

Kathy

Thank you, Kathy!

Thank you, Dave. What drew me to the pails was obviously the colour and their arrangement on the rail. Glad you like it too.

I always enjoy your articles Farhiz, I enjoyed this article, and loved the images, the pails image is spectacular. Thank you for inspiring me to get out once our lockdown.

Best wishe

Dave

This must be Mountain month, Viewfinder also has article on Himalayas. Thank you really liked this trip, felt like I was in your backpack. Loved the pics, you should contact Viewfinder submit your article to show another area.

John, thank you. I will check out Viewfinder if only to see what they’ve got.

Thank you Farhiz for taking me to a part of the world that I tend to overlook as I think about the Himalayas and the tea plantations. I enjoyed the story and the photos which illustrated the article so well.

I think I see that the notched stair has been turned upside down, presumably to stop animals or children climbing it. Just two days ago I was talking with an insurance company about the need to tie a board on the first six feet of a ladder to stop people climbing it. Different parts of the world with a similar solution to a similar problem.

Yes, Kevin, the log ladder has been flipped inwards probably as you point out to deter animals or children from climbing it. But this and other contraptions must be mastered if one has to live in these parts. Wait till I show you some of the rope and plank bridges that connect the remote villages in the hills, I didn’t have the stomach to negotiate quite a few of them, while kids ran down them merrily.

Thanks Farhiz for a wonderful article about a part of the world which very few outsiders know about. I see that the territory is still disputed, but thankfully there are just the occasional skirmishes rather than full out war. I am glad that you can visit the territory, which is part of your own country, and I look forward to your further articles about this little known part of the world.

William

Well, fingers crossed that good sense will prevail one day soon, William. As we speak, there are tens of thousands of troops from both sides stationed along a part of the border. Yes, it is a good thing that we can visit these remoter parts still. And once the virus is controlled I intend to do that again.

Wonderful article and images Farhiz.I heard of the Sino-Indian skirmishes last year in Ladakh but did not know of the 1962 Sino-Indian war. The road to Se La pass reminds me of the roads in Buthan which is just next door to that Indian area. I love the atmosphere of the Se La pass tearroom under the snow and the adjoining image of the husky. You’ve made your camera shine. Thanks for sharing and looking forward to your next articles.

Jean

Thanks, Jean. We are so close to the Bhutan border at times on the road that the cellphone picks up the Bhutanese network Tashi Delek welcome message.

You are a fantastic guide, Farhiz. Thank you. Such informative pictures.

Thank you, David. Sorry to reply to the comments so late. I was expecting the article to come up on a Friday as usual and didn’t expect it on a Thursday. Also, something seems to have stopped me from getting email notifications on new comments.

Beautiful article and pictures Farhiz! Thank you for sharing. Andrea

Thank you, Andrea.

Hello Farhiz,

Thank you for writing this article and enlightening me about an area I knew very little about and know I will not be able to visit.

Your camera did a very good job in capturing your journey and I look forward to reading an article in the future about Tawang itself.

As I am locked-down here in Suffolk, England, I took the opportunity to research the history of the area and particularly the events which led up to the Sino-Indian war of 1962. I also found out that a tunnel is being built or proposed under the Se La Pass. What is the current situation?

I also read a previous article of yours about the battle of Imphal-Kohima and as an ex-military person I found seeing the photographs of the actual landscape really interesting.

Chris

Hi Chris, BRO are constructing two tunnels and a new alignment of the road. The work is expected to be completed by the end of 2021 according to a report in the Arunachal Observer. It is expected to cut travel time by an hour and distance by about 10 km besides giving all-weather access to Tawang. A part of the experience for a traveller, though not so much the locals, are those hairpins which the tunnel hopes to bypass. As a former military man if you have an interest in battlefield history, specially around WWII, then I can recommend you take the Battle of Imphal tour in Manipur one day.