I woke to clear blue skies. From the Dolma Khangsar Guest House’s terrace, I had a bird ’s-eye view of the hill town of Tawang spread around the slopes. To my left was the 80 ft high statue of Tara Devi, the female Buddha on Lumla peak, looking diminutive from this distance. To my right, but out of view, were the white and yellow buildings of Gaden Namgyal Lhatse, or more famously known as the Tawang Monastery, perched on a hill.

Accompanied by my guide Baro, I continued our exploration of Tawang, and this article follows my previous recounting of The Road to Tawang.

A Celestial Paradise on a Clear Night

The Gaden Namgyal Lhatse, built in the 1680s, is one of the largest monasteries in Asia, second only to Potala Palace in Lhasa. It was here that the 14th Dalai Lama spent a few days after fleeing Tibet in 1959. And it was here in the 17th century that a horse led a monk to a serene mountain valley where he built a monastery and called it Tawang—“ta” for horse and “wang” for green pasture.

Precariously situated on the spur of a hill, the monastery is under constant threat from landslides, particularly during the monsoon. There are deep gorges to the south and west, a narrow ridge to the north and a gradual slope to the east.

In the photo above, two large buildings, the Dukhang and the library overlook the residential quarters for young Monpa monks and novices who are trained from an early age in the Gelugpa sect of the Mahayana school of Buddhism. Today, it is a home away from home for 400 young novices. A tall pole called a Darchog in the monastery courtyard is used to string up prayer flags.

Baro and I arrived at the monastery quite early the first morning but not early enough to catch the young lamas enjoying their first assembly of the day. Instead, we went looking for a cup of tea. In a large complex such as the Tawang monastery, there is no shortage of kitchens. They are huge operations, capably of feeding 400 lamas at a time. The key lay in finding one small enough where we could get our chai. I followed Baro into one building and up a flight of stairs. A quick tour of the premises and we settled for one.

Having secured our cups of tea, we went out onto the terrace. We had an unobstructed view of the narrow lanes running through the jumble of monks’ residences.

I am not entirely certain why the rooftops are painted yellow. It could be because the colour yellow in Buddhism is associated with humility and renunciation. Or it could be that Gelug translates to “yellow hat”. Whatever the reason, the distinctive colour can be spotted from miles around and has come to be closely identified with the monastery.

Since it was a nice sunny morning, some of the young lads were up on their roofs, airing rugs and blankets. Finishing our teas, we headed for the Dukhang.

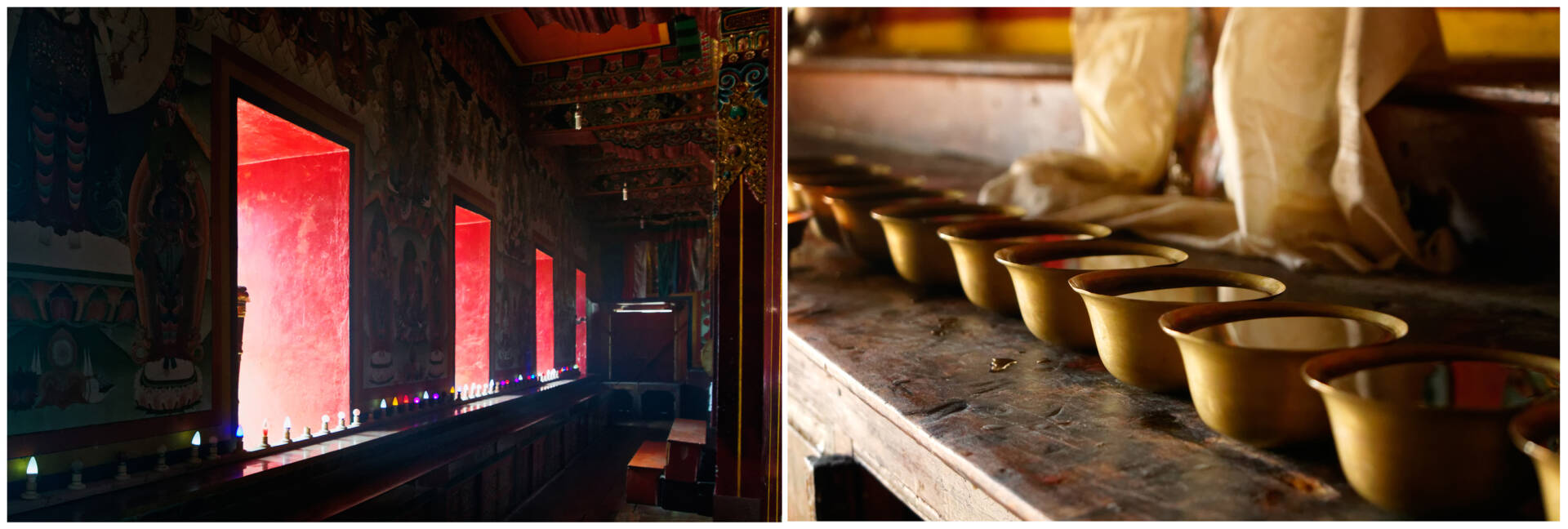

Seven Bowls of Water

Inside the Dukhang, shafts of light cut through the dark interior illuminating paintings of deities along its walls. The early morning assembly was over, and the hall empty. On either side of the nave, brightly coloured rows of mattresses were laid out where the young novices had sat during morning prayers.

Seven bowls of water were placed at an altar as an offering. In Monpa homes, it is customary to offer a bowl of water at the shrine, to light an incense stick and a butter lamp, and recite prayers, including the sacred mantra of Avalokitesvara, Om mane Padme hum.

The Monpa believe in the law of karma—any action or deed will have a corresponding result. All human life results from a person’s past karma, and his or her next life is dependent on the deeds and actions of their present life.

The idea behind Yonchap, as the ritual of offering seven bowls of water is called, is that we should make our donation as freely as we would give water.

The ritual starts with seven clean bowls, called ting, each bowl representing an aspect of prayer, like prostration or confession, and a jug of fresh, clean water. A little water is poured into each bowl, from left to right, until they are almost full to the brim. Mantras are recited throughout.

At the end of the day, the bowls are emptied one by one, starting from the right this time, dried and placed upside down.

The Buddha

Against the north wall of the Dukhang, across the hallway, is a statue of the Buddha seated in the characteristic lotus position, gilded and surrounded by elaborately painted thangkas.

The Buddha himself is draped in a saffron robe. Eighteen-feet tall, he towers over the votaries offering prayers. We had to take the stairs up to the second-floor balcony to get a better view.

The altar was adorned with images of the Dalai Lama, other divinities, butter lamps, water vases, and several other ritual articles. A couple of Tibetan dharma drums in the typical green painted parchment were placed by the side, one more ornately decorated than the other.

Tsering Wangmu

We next headed out to pay a visit to an Ani Gompa, as a monastery for nuns is called, where we met Wangmu.

Tsering Wangmu is from Kitpi, a Monpa village in Tawang. She was eight when her parents died. Her older sister, unable to look after Wangmu, had no choice but to leave her in the care and instruction of the Thukje Choeling Nunnery. Her day is divided between routine chores and study. In all likelihood, she will spend her entire life at an Ani Gompa.

The tradition of sending a child to a monastery has its basis in an economic and religious rationale.

In Tibet, a “monk-tax” levied on families prompted parents to send a child, usually the second son, to a monastery. The oldest would stay back to care for the parents, marry and carry on the family lineage.

Families with many sons were more likely to send off one son and at times two to a monastery. These are decisions that the parents would make, the child being too young to decide for himself. Conversely, if a family had more than one daughter, it became a financial burden to marry them all off well. However, there are fewer nunneries than monasteries. Then there is the strong belief in the afterlife—that the parents or their child would be reborn in a better life—which is another compelling reason to send a child to a monastery.

To the sound of barking dogs

One morning, Baro and I set out from Tawang for the village of Kharman and Zemithang. Near the Bhutan and Tibetan borders, it is a 180-kilometre round trip. We made several stops on the way.

We paused on the road below Khinmey Nyingma Monastery, almost hidden from view behind a thicket of trees. Its Monpa name, Khi-Ket-Nyan-Mey, translates to “a place for listening to the sound of barking dogs”. According to folklore, when the area was a thick forest, hunters would follow the barking of their dogs. One day a hunter by the name of Sonam Rinchin came upon a monk meditating in the forest. Rinchin soon became a disciple of the monk. He gifted the forest land (which he happened to own) for the establishment of the monastery.

Another hour into the drive, we come across Kesang Choten and her sister Lhamu Choten weaving a shawl by the side of the road. Weaving in the northeast is done only by women.

The loin loom was stretched out on the grassy bank. One end of the loom was tied to a rebar set in the ground. Lhamu shuffled back and forth, made a knot at the far end and carried back the wool ball in the little bucket for Kesang to retrieve. After the upper and lower threads were separated, the process was repeated. In this way the length and width of the warp was gradually built.

Kesang and her sister Lhamu must have been well into their seventies, and this looked like strenuous work.

Deliverance from a monkey

A further couple of hours later, we stopped at Gorsam Chorten, a 12th-century stupa built by Lama Sangye Pradhar. Its age may be disputed, but it is still a beautiful stupa.

According to village legend, a six-year-old boy was left unattended in the fields as his mother worked. Lying there, he began to slide and roll down a grassy slope unnoticed. But before any harm could befall him, a monkey, probably a macaque, came to his rescue. The boy came to be known as Sange Pradhar, or “deliverance from a monkey”.

Nestled at the base of veiled mountains, the stupa rises almost 100 feet. Built of stone and mud plaster, its dome rests on three terraced plinths. There are small stupas at each corner. On all four sides, 120 manes, or prayer wheels, are set in a niche in the wall. The dome is capped with a square capital having a spire with thirteen steps topped with a gilded canopy. Four pairs of the supreme Buddha’s all-seeing eyes painted on its capital keep a watchful lookout for evil spirits. Prayer flags streaming from the spire carried their mantras on the wind.

When we arrived there, however, the main doors had been bricked up. Every twelve years, the doors are ceremoniously broken open only for a short period before they are bricked up again. Baro had no idea why this practice is followed. It could have something to do with it being constructed in the 12th century and taking 12 years to build. There are mysteries in the remotest of places…

The People Free of Sin

Soon after leaving Gorsam Chorten, we arrived at our destination. The Nyamjangchu flows below the village of Zemithang near the Tibetan border. In 1959, His Holiness The 14th Dalai Lama crossed into India somewhere near Chuthangmu, fleeing the Chinese invasion of Tibet. During the Indo-China war of 1962, this area came under occupation for a brief period before the Chinese withdrew.

The local name for Zemithang is Pangchen. The people living here are known as Pangchenpa or “the people free of sin”.

The Pangchenpa are by tradition a farming community, growing millet, raising goats and sheep and the odd yak, but all this is changing now. According to Nawang Chotta, the Gaon Bura of Lumpo Village, “When I was young, the entire area of Zemithang was devoted to agriculture. Where shrubs are now, it all used to be agricultural land. Everyone was into farming; they worked very hard. But there were many hardships as well. Wild boar and monkeys would destroy the crops. The animals also come these days, but earlier people knew how to handle them.”

As an explanation, Dorjee Nima, a former personal assistant to Deputy Commissioner of Tawang, adds, “The reason behind our leaving agriculture is because there are now many alternative jobs as a result of the army presence here. Many of us find work as labourers now. Because most of us are engaged by the Army for labour, we have stopped our agricultural practices.” Then as an afterthought, he continues, “This is a backward area; we are not highly educated, so we don’t want to let go of agriculture totally. We want things to improve.”

The Womenfolk of Kharman

After a quick lunch at Zemithang, we headed to the tiny village of Kharman. Leaving the car, we spent the next hour wandering around on foot. The first people we bumped into were a bunch of kids. Baro had brought with him a bag of whistle lollipops from Tawang and soon the valley echoed to the shrill of whistles.

The few whitewashed stone houses were perched precariously on the slopes of a hill. A couple of the kids led us inside their home. The eyes took a second to adjust to the gloom. A wood fire burned in the middle of the room, blue smoke wafting in the air, curling slowly up to the blackened ceiling. Sacks of grain were propped up against one wall. The men were all out tending to their fields or were employed in road construction work. In another home, a young mother fed her child from a bowl of rice.

A 2011 census had counted just forty-four families in Kharman village. I spotted at least one cat.

Outside again, we’d just completed a walk around the village, trudging down mud paths, and were heading back to the car, when from above we heard some women call out from a high window. It was a four-storied stone structure, quite possibly the oldest in the village and, as local lore would have it, once belonged to Dunmu Hashang or the Demon Queen of old legends. But these women folk appeared friendly, and they were inviting us up. Nothing we gestured or said would make them change their minds. So then we climbed back up the path and the stairs.

Quite a gathering of Monpa women folk greeted us. Though they were in the middle of a ceremony, they were just as keen on welcoming us in. There was much animated chatter back and forth, which Baro tried best to translate. Then a bowl, filled to the brim with the local brew, was passed around. Powerful stuff. After a bit, we gathered them all together for a picture. The focus could be a bit off.

The morning assembly

Back in Tawang, the next day’s morning assembly began at the appointed hour, much before dawn. Today we were in time. Baro and I left our shoes at the entrance of the Dukhang and tip-toed in.

Somewhere, a verse was being recited. Young novices sat in long rows on mattresses, wrapped in their vermilion shawls. A senior monk intoned the morning’s prayers. Now and then, a headmaster monk admonished a particularly mischievous young lama. Each one received a bowl of yak milk to drink.

Some of the smallest ones found it hard to stay awake. Some were curious. We tried our best to be as inconspicuous as possible. Prayers lasted for an hour and a half, and then there was a mad rush for the door.

Once outside in the courtyard, the young novices queued up for breakfast. Breakfast is prepared in one of the large kitchens we saw earlier that could cater to four hundred hungry mouths at a time. It consisted of flatbread and chole, and if a senior novice pulled rank on a little fellow and stole his chole, that was just too bad for the little chap.

Last stop

Before we left Tawang, we made a last visit to see Tara Devi on her pedestal on Lumla peak. She was still getting ready. When she finally is, she will sit serenely on a thousand-petalled lotus looking out over the land chosen by a horse.

All photographs were taken with a Panasonic LX100 and Leica DC Vario-Summilux 24-75mm f/1.7-2.8 fixed lens.

Anyone interested in knowing more about the Pangchenpa should seek out Manju Borah’s film, ‘Bishkanyar Deshot’ (In the Land of Poisonous Women), a tale about a superstitious belief among the Pangchenpa, set in the mountains of Zemithang.

Read more articles by Farhiz Karanjawala

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

What a cracking read, and this early in the week too. Loved it.

Thank you Farhiz for sharing your journeys, and your wonderful images.

Best Wishes

Dave

Glad you enjoyed it, Dave. Thank you.

Farhiz,

I enjoyed this very much, particularly the way you structured and illustrated the various episodes of your journey. I waited to comment until I had viewed the article on a large screen and I’m glad I did as I then saw the monk leaning out of the window looking over the rooftops. A nice moment well captured. The light on the water bowls is beautiful.

Thanks, Kevin

Thank you, Kevin, I’m glad you got to view the photos on a bigger screen. Mike was kind enough to enable larger viewing.

Thank you Farhiz, a vert interesting article with beautiful photos!

Thank you, Andrea, one only has to dig a little bit deeper before all the village folklore spills out.

Lovely story and photos, Farhiz. I must mention the work of Steve McCurry once again not only because of the content, but there similarities in style. As a second son myself, I winced when I saw what was the fate of second sons, but I have long since learnt not to be judgemental about different cultures. You mixture of atmospheric indoor photos with dramatic landscapes showing the locations of dwellings and monasteries is very effective. You are definitely closer to Heaven in those places.

William

Thank you, kind sir! McCurry is a legend. As a second son you could have called your book The monk with the Leica. Arunachal is one of the most beautiful states I have visited.

Thank you Farhiz for taking us armchair travelling once again.

Your indoor images demonstrate the strong capabilities of that f1.7-2.8 Leica short zoom, combined with the depth of focus of the smaller sensor in those indoor shots. I too particularly like the wood fire smoke pair, and also the two angular light beams sun ray images.

The Lumix LX100 and it’s Leica D Lux 109 clone are great compact travel cameras. Not the latest and greatest, but very capable of catching good images in the right hands.

Thank you Wayne, yes I loved the LX100 and if I hadn’t been given an X Vario I’d still keep using it.

Thanks Farhiz for a wonderful article and set of images. My favourite images are the ones taken within and outside people’s home. The landscape of the region reminds me of Bhutan which I visited 5 years ago. I thank you as for advising me Abbas book the gods I’ve seen which I bought recently. You’ve made your small LX100 shine and seeing images of the Himalayas gives me a huge breathe of fresh air in these virus-troubled times.

Stay safe

Jean

Thanks, Jean. In fact some of the places are very close to the Bhutan border so the topography would be fairly similar. I knew that we were close when I got a Tashi Delek message on my cell phone.

Fantastic!! Love wood smoke, female Buddha and prayer flags(?) next frame. Now I think you and Jean, and John S and Wayne should go into business to rival Magnum call MAC4. Become specialized and just sell your photos to travel agencies for that whole region you guys photo. Thanks again for your effort and this gorgeous final result!

Thank you John. For now I’d stick to being an unknown amateur – that way there is no pressure on what I choose to photograph. But some of my favourite Magnum photographers are Kertész and Haas.