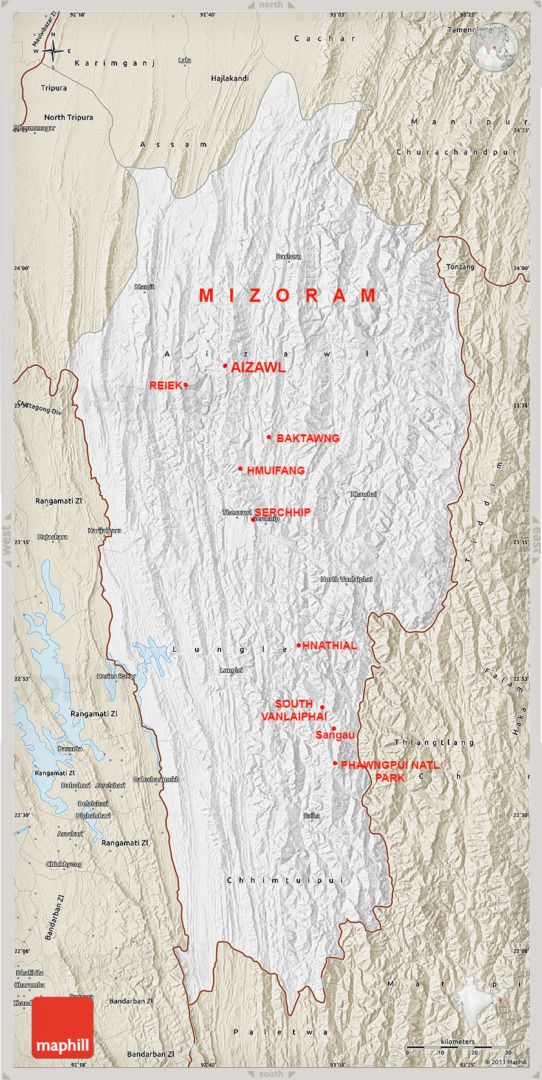

From Sangau, Mizoram, in northeast India, the Arakan range across the border in Myanmar comes into view. Just under 1,000 kilometres in length, it includes the Lushai Hills in Mizoram, the Chin Hills in Myanmar and the Naga Hills that straddles both countries. We drove up a dirt road to the highest point in Mizoram—Phawngpui—in a National Park Ranger’s Bolero pickup. Standing out there on the edge of the track, it looked beautiful and peaceful.

It all began back in Delhi, one November day, with an email from Bornav and Vaivhav waiting for me in my inbox. It was a confirmation of my upcoming trip the following January to Mizoram. I’d picked the Blue Mountain tour that would start from Aizawl, the state capital, and take in places I was hearing about for the first time—Vanlaiphai, Hmuifang, Hnathial, Sangau, Phawngpui, Reiek, Baktawng.

Aizawl—Silent Night

One day, to give me an idea of the size of the town, Rina and Hruaia (pronounced Shu-ai) drove me out to a point in another part of town called Zemabawk. Here one gets a panoramic view of the city. Through the afternoon haze, the city’s sprawling development was evident. Aizawl’s 300,000 inhabitants occupy a ridge that runs north to south, that is right to left in the photograph above. Commercial and business centres, government offices, hospitals, schools and colleges, churches, temples, mosques and playgrounds, compete with residential localities for space.

For my first night, I was booked into a hotel in the busy Zarkawt area. A night in the heart of any bustling Indian town may not help in getting a good night’s sleep. The traffic can be ceaseless and horns persistent. But Aizawl is different. Not a driver sounds his horn. Citizens pride themselves in Aizawl being a silent town. It was the first city in the country to ban the use of horns, a ban that now covers the rest of the state.

From the hotel window, I witnessed the Mizo traffic discipline first hand. Maruti 800s, Tata and Mahindra SUVs, bikes and scooters ruled the road. The slowest vehicle in the line set the pace. If a City Bus stopped to let passengers on or off, the cars behind would wait. I didn’t see impatient drivers overtaking. Only the ones on bikes or scooters were allowed to do that. Anyone on foot had to necessarily share the road with the vehicles that were parked or moving, which, as any Indian worth his or her salt, did expertly.

A DIY MPV

By seven the next morning, Maliana, Hruaia and I were on the road in an attempt at beating the traffic that would soon descend on Treasury Square and our southbound route out of the city. We headed into mountain country. The road snaked along the ridge top, at times dipping low, at times making a sharp manoeuvre to avoid an outcrop. To our right and far below flowed the Tlawng, hidden beneath a blanket of thick cloud. Somewhere to our left flowed the Tuirial.

Despite reports that Mizos wake at five, have lunch at ten and are asleep by six, I can vouch for only one trait. We had made a brief stop, an hour-and-a-half from Aizawl, at Hmuifang for tea and, I guess, for Maliana to re-confirm our bookings for the return trip, before proceeding on to a wayside restaurant in Thenzawl. By ten-thirty in the morning, we were ordering lunch. As a certain Mizo guy I know on the Interweb would say, “Lolz”.

Retracing our route back from Thenzawl, we caught up with the NH2 passing through Rawpui in the district of Lunglei.

A common sight along the mountain roads in Mizoram were versatile do-it-yourself multipurpose carts called “tawlailir”, with a wooden lever for steering and braking. I saw them being used to haul firewood, bamboo, sacks of grain, a gas cylinder or two and people. Any respectable village home will have one parked outside.

A folktale about a river

After Rawpui we passed through Hnahthial, turned left off NH2 and took the road to the village of Tuipui D.

The Mizos had no written record of their culture or traditions before the arrival in 1894 of Christian missionaries to the Lushai Hills. Folktales were narrated by one generation to the next. One that has survived the modernising effect of education and the influence of Christianity is a tale of the girl who saved her village.

The tale goes like this: Once there was a young orphan called Ngaitei who lived with her grandmother. They would go together to the forest to collect yam. Nearby was a lake in which the young girl’s father had drowned. The grandmother had warned Ngaitei never to say “Ho” when near this lake.

Feeling thirsty one day, she approached the water’s edge when curiosity got the better of her, and she shouted “Ho”. No sooner had she uttered the word, her father appeared before her as a ghost and spirited her away. Ngaitei’s grandmother waited and waited, but when the girl failed to return, she went in search of her.

She asked a pair of red deer whether they had seen her, and they replied, “We saw her on the other bank of the Tuipui and Tiau rivers where her father has taken her.”

Next, she asked a pair of partridges, and they replied exactly as the red deer had done, “We saw her on the other bank of the Tuipui and Tiau rivers where her father has taken her.”

Upon reaching the spot and finding Ngaitei there, she bargained with the father to take the girl back. He reluctantly agreed to let the girl go on the promise that she be returned to him in a few days. Alas, the promise was never honoured whereupon one day the furious father caused a large flood that threatened to drown the village where Ngaitei lived.

In desperation, the village folk threw a piece of cloth that belonged to the girl into the floodwaters. The waters abated but only for a while. Then it began to swell again. The villagers then threw a comb that belonged to the girl into the waters. But it wasn’t long before the waters began to rise again. This time, they gave the girl up to the flood, and it subsided forever, thus saving the village.

Darzo—a buried history

Our route to the Blue Mountain took us past a place called Darzo. At the time we drove up the mountain to the Darzo viewpoint I had no knowledge of the history of this beautiful place. I came across a Mizo Civil Servant’s Reflections only later, and it was a painful account to read. It was in the days of Mizo insurgency and before the formation of the Mizoram state.

Darzo, the account reads, was one of the richest villages that the Officer had ever seen, with ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. His orders were to clear the village of its inhabitants and set fire to the huts preventing it from falling into the insurgents’ hands. The villagers were to be resettled in Hnathial under the protection of the government security forces as part of a wider village resettlement scheme. (The aim was to drive the insurgents into the jungles and cut off their recruitment and supply lines.) But as night approached, he failed to persuade them to set fire to their homes. The Officer then gave the order to his soldiers to torch the village, setting the first house on fire himself.

The account continues to describe the events that unfolded. “There was absolute confusion everywhere. Women were wailing and shouting and cursing. Children were frightened and cried. Young boys and girls held hands and looked at their burning village with a stupefied expression on their faces. But the grown men were silent, not a whimper or a whisper from them. Pigs were running about, mithuns were bellowing, dogs were barking, and fowls setting up a racket with their fluttering and cracking. One little girl ran into her burning house and soon darted out holding a kitten in her hands.”

Then they marched out of Darzo. The Officer continues, “We walked fifteen miles through the night along the jungle, and the morning saw us in Hnahthial. I tell you, I hated myself that night. I had done the job of an executioner. The night when I saw children as young as three years carrying huge loads on their heads for fifteen miles with very few stops for rest, their noses running, their little feet faltering…for the first time in my life as a soldier, I did not feel the burden of the fifty pound haversack on my own back.”

Mizoram became a state in 1987 following successful peace talks between the Indian government and the rebels. Unfortunately, Vala, the school principal we bumped into in Darzo, was probably too young to have any recollection of those days.

Blue Mountain

The early morning mountain air was crisp and cool, with a thin veil of mist hanging in the air. The RD Rest House, a tourist lodge in Sikul Veng, South Vanlaiphai, faced east with a wide patch of cleared ground in front. Bright sunlight bathed the valley.

To reach Phawngpui, we first made a stop at Sangau, a village with a population of just over a thousand, making it one of the largest in the state. There Maliana recruited the services of Chanuka, an accredited National Park Ranger, who would drive us up to the peak in his special 4-wheel drive pickup.

We made a short detour to Thaltlang village, where a young girl at the ticket booth handed us our passes to Phawngpui.

The approach to Phawngpui (elevation 2,157 m) was by a narrow treelined track of mud and rock. The jeep bounced and swayed across the rutted path as Chanuka wrestled the steep hairpin bends up to the top. I was lucky to occupy the sole passenger seat. Not so lucky were Maliana and Hruaia, who held on with both hands to save themselves from being tossed out.

Phawngpui owes its more romantic name, Blue Mountain, to the cloud cover that usually sits atop the peak, making it look blue from a distance. The top of the peak is actually a large meadow. On the western edge, the meadow falls away in a steep drop called Thlazuang Khàm. We had the mountain to ourselves. The government of Mizoram only gives out permits during the drier months of November to April. I must have been one of the 569 visitors that year.

The Mizos have long imbued their mountains in folklore. The mountains were said to be the abode of demons. Phawngpui holds a special place. The demon that inhabits it goes by the name Darkualpa, brother of Tiauchhumpa. Together they care for the animals that live there. Demons marry amongst themselves. When that happens, it is said, they exchange gibbon apes, morning mists and hawks as gifts. For wedding gowns, they use pine trees.

Back at Sangau, Chanuka invited us in for a cup of tea.

It might be dangerous…you go first

Reiek was our next destination, a mountain peak barely 30 km west of Aizawl. I had been joined by another guide, Rina, standing in for Maliana, who had to return to the city.

Reiek is 4,872 ft. high. The trek up was first by a path cut through the thick undergrowth. Then we followed a path that wound through the hills, at times running alongside steep drops, past a spot where an unfortunate hiker met his fate, till finally, we burst into the tall open windswept grass on the mountainside. From then on, we had a clear view of the top.

In Mizo folklore, Reiek was said to be protected by the demon Khawluahlali. One day some mountain demons declared war on the Reiek mountain demon. They summoned the Tlawng river demons to assist them. The Tlwang demons dashed their waters against Reiek with great force. But they failed to shatter the rock. Defeated, the chastened river had to curve and change its course.

Hruaia, on reaching the top, clambered up onto the rocky outcrop that jutted out over the precipice. I hoped some demon was looking out for him.

Solomon’s Temple

One day, Rina and I drove just outside the city limits to Solomon’s Temple. What began on Christmas Day in 1996 slowly grew through the perseverance and patience of one man to become the temple it is today; a white marble edifice with four towers and four pillars, each pillar carrying seven Stars of David, each tower carrying a crown.

Inside, along one wall, a stage had been set up with a banner, emblazoned with the church emblem of a crown, announcing its recently concluded annual convention.

Ever since Lalbiakmawia Sailo had a dream of building Solomon’s temple, he has relied solely on donations from well-wishers and the faithful to make additions to the structure. Today the great hall was empty. Work on the building wasn’t finished yet. Seeing that the church pews were all lined up at one end, one might assume that it was the turn of the bare earthen floor to receive the next largesse.

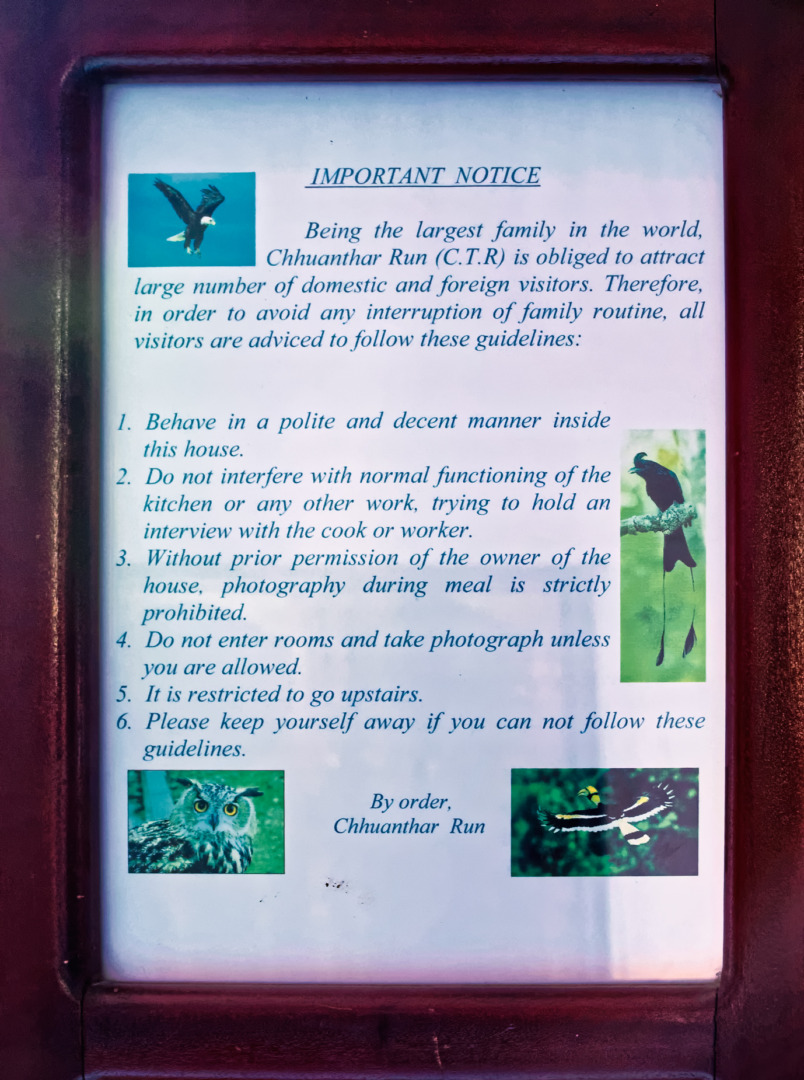

Chhuanthar Run

By now I had rated my Mizoram trip a big thumbs up. But Rina had one final treat in store for me.

I was spending a night at the Tourist Centre in Beraw Tlang as the hotel in Aizawl had been booked up by a visiting football club. Just a couple of hours drive from here was the village of Baktawng, home to the largest family in the world, Chhuanthar Run. A visit there sounded like the perfect end to a fascinating trip.

Upon reaching the multi-storey family home of Chhuanthar Run, painted in a distinctive purple, we were met by a family member and welcomed inside. A sitting area for visitors was set out with long wooden benches placed along the walls on the ground level. Off to one side was a kitchen, a long, large room lined with cupboards and shelves stocked with utensils. Already the kitchen was buzzing with activity. The patriarch’s wives prepare all meals in the Chhuanthar Run home.

Pu Ziona was not at home when we paid a visit. He was, as per his daily routine, up at five and working his fields with other members of his family. A daughter went into a room and soon returned with one of the wives to sit with us. Tluangi is the second wife. She showed us around. Along one wall in the large hall were framed photographs of sections of the family.

Pu Ziona has 39 wives. And they all live in harmony. It is the job of his first wife, Zathiangi, who he married in 1959, to manage all household matters, draw up the conjugal roster and settle any rare dispute that might arise between wives. Their 86 children, 40 sons and 46 daughters, are assigned tasks in the fields, workshops and schools according to a roster drawn up by Pu Ziona. Married daughters stay in their own homes in the village. Everyone helps take care of the 128 grandchildren.

Zionnghaka, or more popularly known as Pu Ziona, is the septuagenarian head of the Christian sect called Chana Pawl. Founded in 1942 by the late Khuangtuaha, Pu Ziona inherited the leadership of the small community they call Chhuanthar Kohhran, the “Church of the New Generation”, on the death of his father Challianchana or Chana for short.

Its style and method of functioning—the practice of polygamy, isolation from mainstream society—is often interpreted as a resistance against the church and society. But unlike some Christian and other religious movements that have seen a decline in membership after a few years, Pu Ziona’s community has achieved an astonishing amount of economic and social self-sufficiency.

The community has its own church, schools, metal and wood workshops, even a stadium. Members of the community follow a strong work ethic. Together they have been instrumental in reviving the art of making traditional utensils, door panels, tables, beds, cupboards, and window frames. Of the 140 households in the village, 85 are engaged in carpentry work in its 15 wood workshops. The income earned from these activities gives the community economic independence with minimal interaction with the outside world.

Instead of celebrating traditional Christian festivals such as Palm Sunday, Good Friday and Easter, the community celebrates the birthday of their founding fathers and other family events. Christmas is the one Christian festival that is celebrated.

Tluangi waited as we finished our tea and then led us outside. Down the road, a few women were busy painting a plywood sheet. I went over to give them a hand.

All photographs except where noted were taken with a Panasonic LX100 and Leica DC Vario-Summilux 24-75mm f/1.7-2.8 fixed lens.

POSTSCRIPT

The death of Pu Ziona

Pu Ziona, the head of the “world’s largest family” died in June 2021. Here is a report from NDTV.

Read more from the author

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

What a very beautiful scenery of Arakan hill range. Can i use the picture for book cover?

Thanks Kevin. The trail you’re referring to is actually a wire reflection. At least that’s what it looks like in the larger view. As far as the photo of myself goes I think there’s an idea that Mike might consider, if it’s possible — there could be a page on Macfilos where all the contributors and regulars can put up a photo against their names. All voluntary of course. That way everyone can put a face to a name.

A very interesting article beautifully illustrated Farhiz, thank you. In the photo of the red chillies is that an aircraft trail in the background? If so it would show how high up you were. Perhaps I’m imagining it. Anyway I enjoyed seeing the front facing picture of yourself, it puts a face to a name.

A wonderful article Farhiz. Village life in Thaltlang and the two shots in Sangau are my favorites. You’ve made your lumix shine. Thank you

Jean

Thank you, Jean. This article actually took the longest time to write. Partly because Covid struck me and the family midway. But all turned out well in the end.

Thank you Farhiz, for this travelogue.

Particular images that are favourites for me are the two Sangau village shots and the Tuipui River. Glimpses well caught.

Thank you, Wayne. The one with the red chillies is my favourite as well.

Lovely story and photos as ever Farhiz. You are certainly building up my list of ‘must see’ places that, I must admit, I have never heard of before. The striking features include the inverted clouds and the blue buildings, a bit like those in Jodhpur.

I’ll take my hat off to any man who first got married in 1959, has 39 wives and still needs a conjugal roster!

William

Thank you, William. You know, Ireland is a country I’d love to see, and not just because we had Irish brothers as our teachers in school.

Just let me know if and when you are coming here, Farhiz. I had missed the Postscript about the Pu Ziona passing away. I am 4 years younger than him, but I’ve only had the one wife.

William

I will. My guess is it would make for a terrific driving trip.

Thank you for taking the time to share this experience with us Farhiz, a wonderful segway into the weekend.

I do look forward to your next adventure.

Thanks, Dave. Hopefully soon.

There were wonderful Segways at ‘Futuroscope’ near Poitiers (and, of course, in that episode of ‘Frasier’) ..but would one make it up the rough terrain “..in Beraw Tlang”?

(Love and best wishes to your Df..)

Playing catch up – so sorry for being late to the game.

I love my Df 🥰

Wonderful story line and photos, really like the noise ordinance on horns. Looks like a serene gentle place to escape the daily grind. Thank you, where you going bring us next? Much Appreciated.

Thank you, John. Yes, I know I’d like to go back again. As for the next piece, it should be a surprise, no?

A very educational article with great pictures. You make me feel like I am there which is wonderful these days.

I can only deal with one wife but do confess to polygamy with my cameras.

Geargamy it’s called

Mike, That cracked me up.

Thank you, Brian. Most of us can only deal with one wife.

Farhiz

Thank you for taking us on an intriguing virtual journey to Mizoram. As usual your photographs bring the article alive.

In Great Britain having more than one wife is illegal and is called bigamy. The late Pu Ziona had 39 wives. What do the inhabitants of Mizoram call this apparently legal practice?

Chris

Polygamy springs to mind.

No. I would call it Punishment!

I don’t know if the practice has been officially legalised, my guess it has not, but rather the state may have taken a hands-off approach. Unfortunately, that’s what the press and public focus on. But with the passing of Pu Ziona, his eldest son will probably assume the position as head of the sect, and with that may end the practice of polygamy.