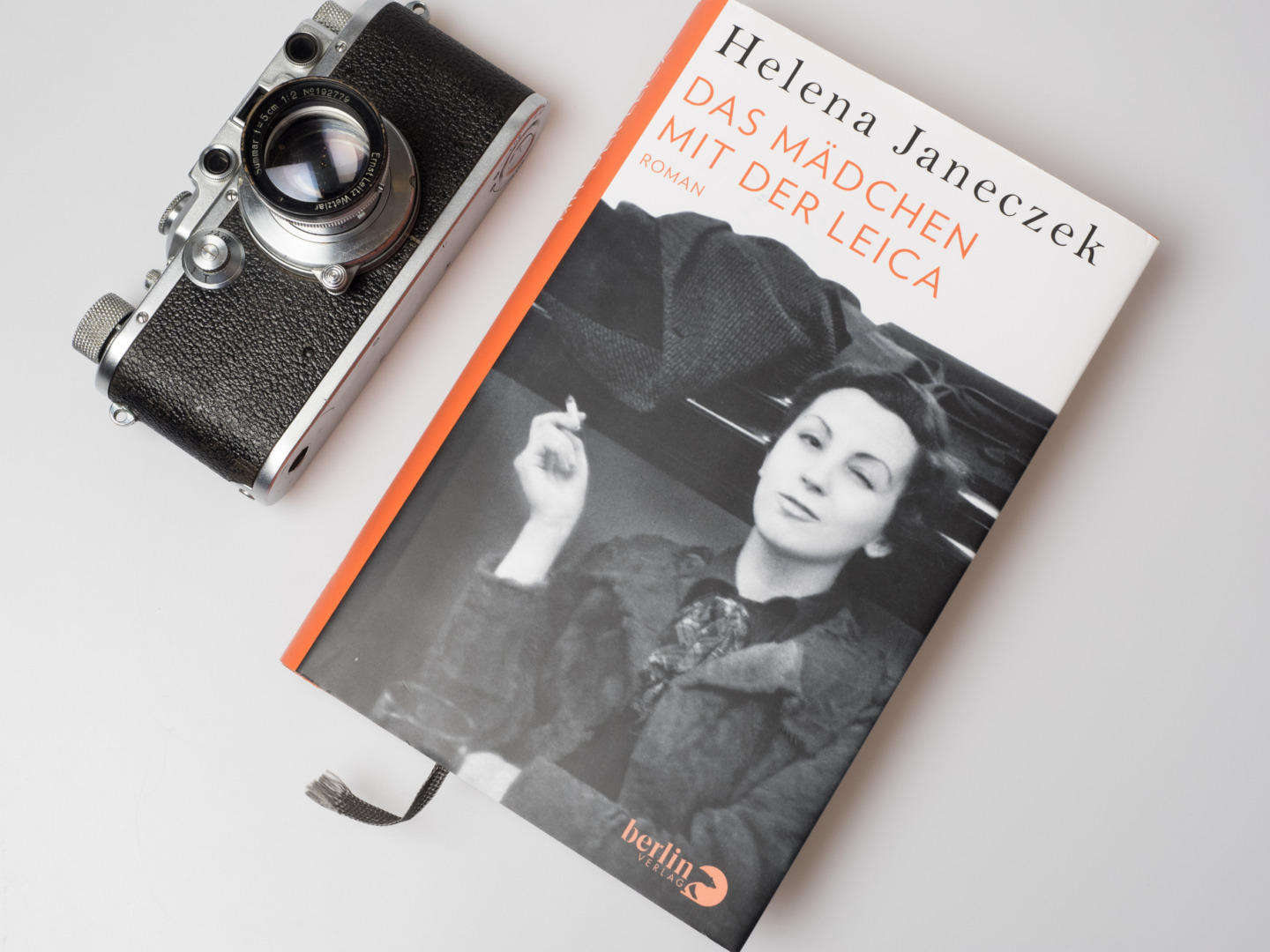

It was the book of the Year in Italy in 2018, but judging from the reviews published, The Girl with the Leica by Italian writer Helena Janeczek had little impact in the English-speaking world.

I ploughed my way through this very special novel that was awarded the Premio Strega, Italy’s most important prize for literature. And I suggest you might use the autumn or winter evenings for this read, too. Not despite, but rather because it is by no means a book about Leicas.

At the book’s centre is Gerda Taro, born as Gerta Pohorylle in 1910, allegedly the first female photojournalist to be killed in a war. She died at the age of only 26 years in the Spanish Civil War. And: She was the companion of Robert Capa, whose name was to become so much more famous.

What’s it about?

First things first: The book is a work of fiction. It constructs a biographical sketch about a person that existed in reality. However, it seems to be very profoundly researched in order to bring back to attention Gerta Pohorylle, later known as Gerda Taro.

The novel has been labelled “bio fiction”, and this seems very appropriate. One cannot praise enough the author’s labours to unearth all the minute detail that turns biography into a life.

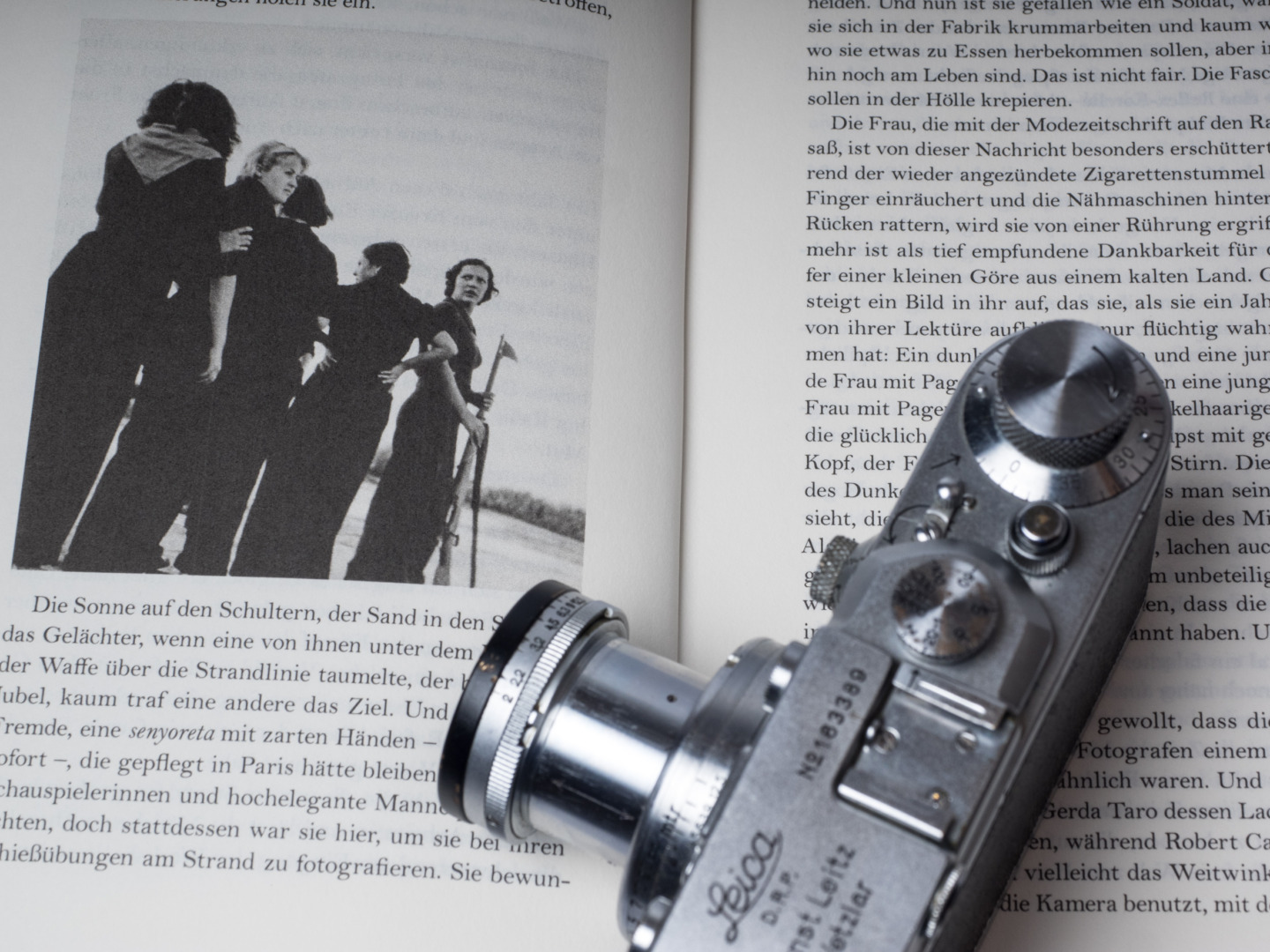

Gerda Taro did not even live to see her 27th birthday and she is described in the book as a tremendously attractive, cheerful, and fascinating personality.

As a young woman, Gerda leaves a middle-class centre-left life in her Jewish family in Leipzig and flees the strengthening Nazis with her friend Ruth Cerf. In Paris, she meets a bohemian group of exiles and ekes out a living with odd jobs. Other companions along the way are Willy Chardack and Georg Kuritzkes, both friends from her Leipzig days.

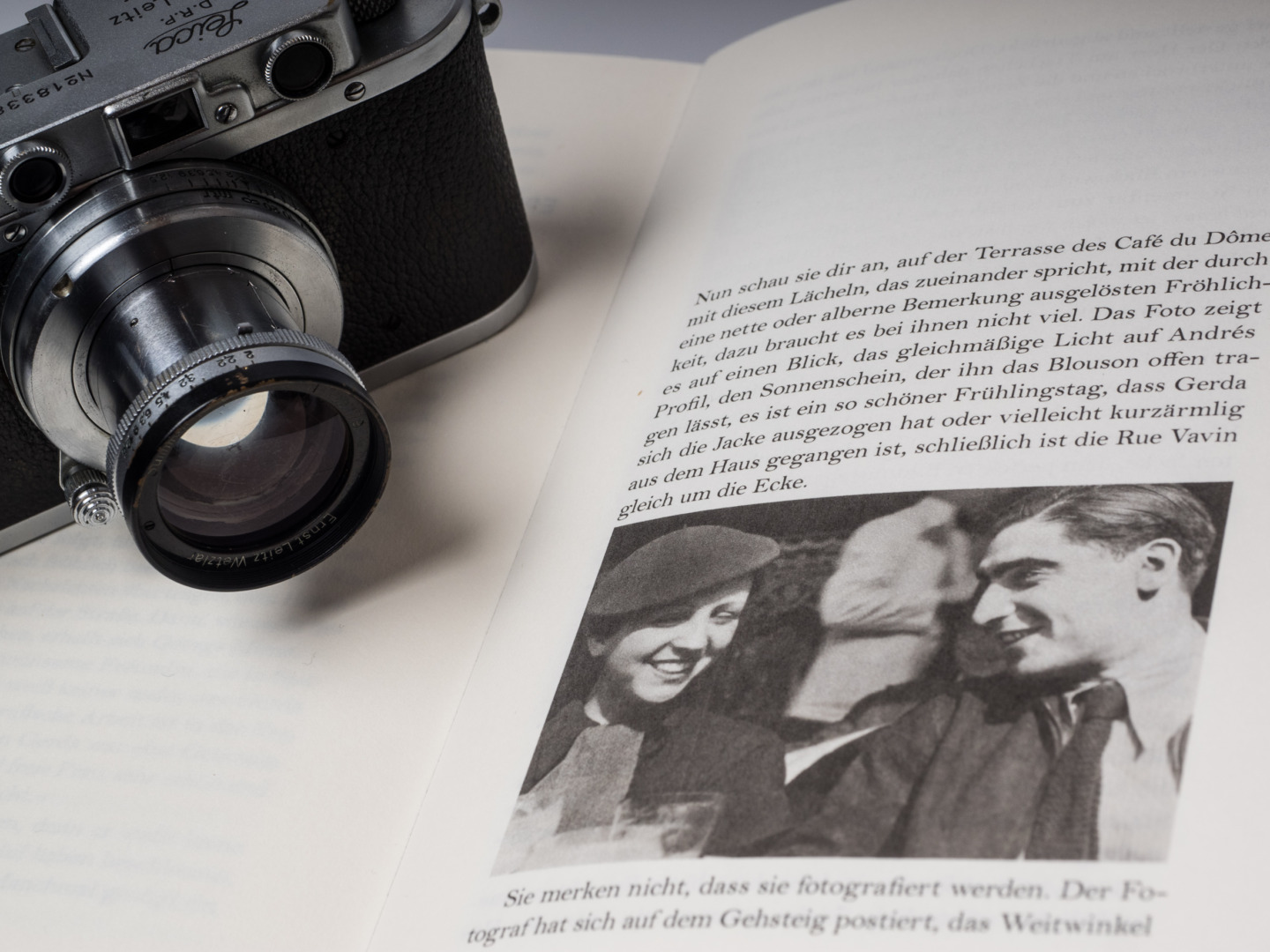

She meets David Seymour (1911, Warsaw – 1956, Egypt) and Endre Ernö Friedmann (1913, Budapest – 1954, Indochina), both aspiring photographers who, after the Second World War, would be co-founders of the legendary international photography cooperative, Magnum.

They are all staunch anti-fascists, and after the military coup in Spain, they are among the many foreign volunteers who support the Republican cause and aim to prevent what ultimately ended as Franco’s regime. Kuritzkes as a soldier with medical knowledge, Friedmann and with him Pohorylle as eyewitnesses with their cameras.

But the names, Friedmann and Pohorylle, fit neither the lifestyle nor the hoped-for international attention. Gerta Pohorylle adopts her pseudonym Gerda Taro in Paris and, as the narrative would have it, invents for Friedmann the pen name Robert Capa, which works so well in so many languages.

Add to this a glamorous legend that somewhat obscures the misery of his past as a refugee from Budapest – and a star is born. Capa becomes world-famous, while Taro, who left such a deep mark on the lives of so many people (especially males), is publicly remembered, if at all, as Capa’s companion.

She dies in an accident between two Republican vessels at the front. On August 1, 1937, accompanied by tens of thousands of socialists and communists, she is buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris; it is her 27th birthday.

How is the story told?

The novel’s core part consists of three chapters. In each of them, a friend of Taro’s muses in his or her memories of this very special person. Ruth Cerf was her best friend and roommate in the Paris exile and looks at Taro from the perspective of 1938. She had become an assistant to Robert Capa, and she has the soberest perception of Taro. In an inner monologue, interwoven with some narrative and short dialogues, she remembers Taro, and her thoughts return several times to the question of whether Taro was true to anyone other than herself. To her boyfriends certainly not, as the two other characters show.

Willy Chardack is hopelessly in love with Gerda, and she knows how to use her power over him. Sure, he is more to her than someone solely to play with – the bonds from the Nazi persecution they suffered together back in Leipzig remain strong. He tells his story from the perspective of 1960. At this point, he is the co-inventor of the artificial cardiac pacemaker in the United States, and he looks back on the disturbing first two-thirds of his life.

As in the Ruth Cerf chapter, the viewpoints of the narration are shifting between Leipzig in the early 30s and Paris around 1936 and 1960. The reader doesn’t know when the episodes and thoughts they are reading are set in time. But it does not really matter; this is literature and not a CV.

Georg Kuritzkes comes into the plot by means of a fictional telephone call with Willy. He is in Rome now, works for the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, and has connections to other men with partisan pasts. In 1960, the events from 25 years before seem to be close and far away to him at the same time. It becomes clear that he was the man who loved Gerda most and who understood best that he would never be able to possess her in any way.

The three main chapters are framed by a prologue and an epilogue. The overture to the novel is a kind of a dialogue between the imaginary narrator and her readers.

Here, a few of Gerda Taro’s photographs are shown, and they serve to introduce her as a sensitive observer and a person with a big emphasis on the impulse of a given moment (that is, someone who knows human nature and is, therefore, a good photographer).

The epilogue reveals in a way how and why this book was written by explaining how a suitcase with negatives from both Capa and Taro was discovered in 2007.

How does it read?

The Girl with the Leica is a highly artful book. The story is narrated in a non-linear way, with shifting perspectives. As a reader, you do not always feel you are on really safe ground. This is, of course, deliberately evoked by the author: The allegedly objective character of photography as a medium gets undermined in a more or less subtle way. This fits the somewhat dazzling figure of Gerda Taro (who is denied the opportunity to tell her story herself), but it requires careful and slow reading.

I read the novel in German and it took me two attempts to find my way into the book. It’s certainly not the translation, and the English version seems excellent, too.

As Jamie Mackay wrote in The Guardian, he finds Janeczek’s book “daring”, and I agree. It takes some courage to read it, and how much more courage must it have taken to write it in this manner?

The result is a demanding read, but also a powerful narrative that never comes dangerously close to romanticism, kitsch, or pathos. All in all, the ambitious undertaking of writing this novel, in such an artful way of organising its contents, does not miss its effect.

For those interested mainly in photography, the prologue and the epilogue might turn out to be the most interesting parts of the book. But even these readers might very well be intrigued with the story of Gerda Taro in which photography is just one facet.

Is the book title misleading then? Well, “The Girl with the Leica” might well trigger more interest for the novel and its protagonist than, say, “The Photographer who Died in the Spanish Civil War” or “A Girls Goes Her Own Way”. This will surprise Macfilos readers least: Leica is a world-renowned brand, period.

How did the author find her topic?

In way, it is no surprise that Helena Janeczek of all writers took on the life of Gerda Taro. Born 1964 in Germany to Jewish holocaust survivors, she has an evident biographic connection to her subject matter and shares no less than a trauma with the protagonists of her novel.

Janeczek moved to Northern Italy early in her life and has become so much at home in Italy that she writes in Italian now. So, the novel was first published as La ragazza con la Leica in the Italian language, with translations in many languages to follow.

In interviews, Helena Janeczek pointed out that she had a long-standing interest in Robert Capa and his (world-famous) legacy. A crucial basis for her book, however, was Imre Schaber’s work.

Schaber is the one who really discovered, or rather, re-discovered, Gerda Taro and her work. Schaber wrote biographic books on Taro (non-fictional), collected a great corpus of documents about Taro/Pohorylle, and she curated exhibitions about the photographer who was so much more than Capa’s companion.

Helena Janeczek’s admiration for Gerda Taro is undeniable. But – and this is a great achievement – this admiration never obstructs the author’s boldly clear view of her subject.

That is why The Girl with the Leica is of course a book about the emancipation of women at that time, but not a work of feminism. It is a book about history, in which, besides Capa and Taro, David Seymour and Csiki Weisz, marginally Henri Cartier-Bresson and numerous historical personalities from Willy Brandt to Varian Fry appear, but it’s no history book.

And what about the Leica then?

When you are reading a book called “The Girl with the Leica” and you’re into the history of photography as well, you’re tempted to ask: And what Leica did this girl use then? At the start of her photographic career, she used a Rollei in fact, as the English Wikipedia article on Gerda Taro explains with reference to the square negatives.

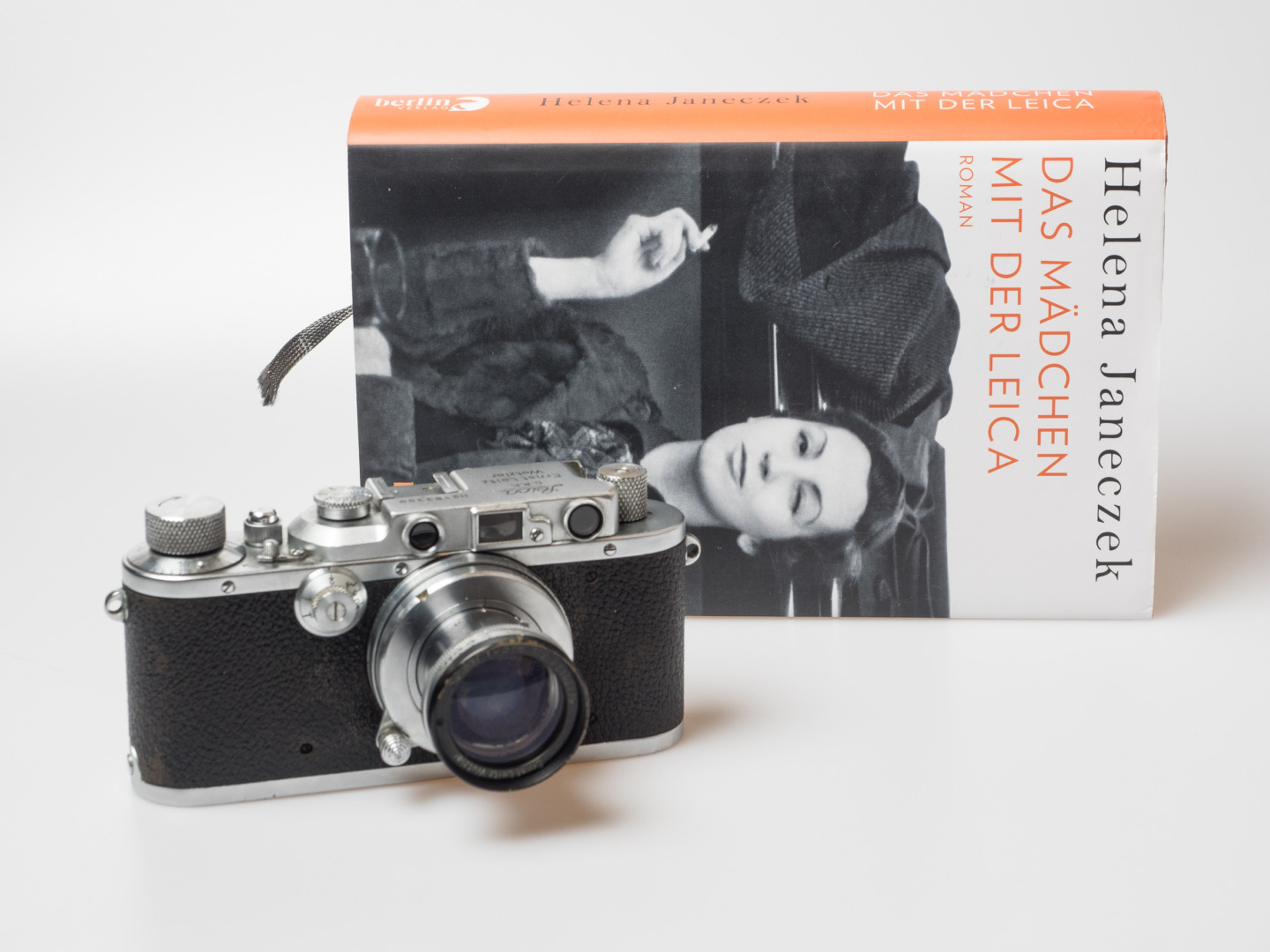

However, there exists a photo of Taro with a 35mm camera. It was taken in 1937 and shows her working with what appears to me to be a chrome Leica III (or an earlier model updated to this standard). The Leica III was quite new then (released in 1933) and certainly a state-of-the-art outfit for a serious journalist.

William Fagan and others certainly know better, but I see in the only photo that is known to me of Taro with a Leica a strap hanging down from both sides of the camera. The lugs for it were only introduced with the Leica III according to Erwin Puts (see images in Leica Compendium, p. 209). The lens on the camera in Taro’s hands was identified as a Summar 5cm 1:2, the faster standard lens for screw-mount Leicas in those days.

Being absolutely no expert in LTM cameras, I was lucky to hold such a combination (body #183389, manufactured in 1935; lens #192779, from 1933) in my hand, and I immediately perceived what an attractive tool this must have been.

Whatever happened to Taro’s camera I did not find out. Was it destroyed in the fatal accident? Did Robert Capa use it afterward? Did it remain in Spain, Paris, the United States? But, mind, that is not really important.

After you read Helena Janeczek’s novel, you might be cured of gear-mania for some time. Because The Girl with the Leica shows us that it is people and their relationships, societies and their values, images, and their messages that the whole thing is about (and not Summicrons and sensors).

Not a new insight, certainly, but very invigorating – and in the case of this recommendable novel, the path to this conclusion, while at times arduous, is also very fascinating.

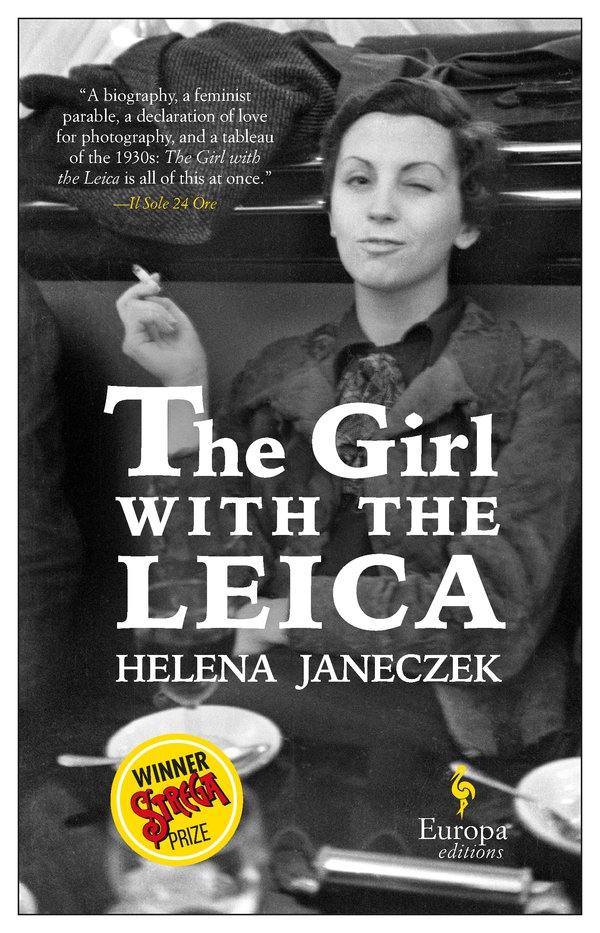

Helga Janeczek, The Girl with the Leica. In English from Europa Editions, paperback or e-Book. Translated into English by Ann Goldstein. The cover photo of both the German and the English edition is by Robert Capa.

Amazon buying links:

The Girl with the Leica

Das Mädchen mit der Leica

La regazza con la Leica

The Leica IIIa and the Leica II for the images in this article were kindly provided by Leica Store Konstanz.

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Using Leica in the title (instead of camera) could suggest that was the reason her photographs were good. Any camera could do them for sure. But Leica loves medals and is always in every soup like Magnum.

I visited Magnum offices in Paris before COVID-19 and among the many boxes of photos we looked at and handled was Capa’s soldier.

It is quite a small print with stamps on the reverse of magazines in which it has been published.

No pretensions about conservation At Magnum , as they said, how many grubby hands have held this print in 80 years? So it was passed around.

My lasting memory of the office is the racks of small stamps with the names of the great Magnum photographers for identifying transparencies correctly and the pin ball machine.

Cheers

Philip

Thanks for the excellent review of this book. I received it as a Christmas gift last year from my daughter in law. I must confess, I found it a bit difficult to embrace and put it down. I’ll have to try to get into it again. I have always been a big fan of Capa and have read several books about him, as well as his own books that he wrote about his life as a photographer.

David Seymour is mentioned in your review. Some know him better as “Chim”. He was also a founder of Magnum.

One recalls the impact of the illustrated weekly magazines such as LIFE. This was before television, and greatly influenced people’s view of the world at large. I remember growing up with LIFE magazine, looking forward to every issue arriving in our mailbox.

I was fortunate in meeting famous LIFE photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt several times. I had always been a big fan and had all of his books. I went to a exhibition of his work at a local gallery where he graciously signed all of his books in my collection for me. I also met him at an LHSA meeting somewhere along the way. He was very charming and unassuming. Quite different from what I imagine Capa to be.

Speaking of Magnum, I have met several Magnum photographers through the LHSA over the years. I have become good friends with Costa Manos, and have featured his work in Viewfinder. Costa was my guest at the LHSA meeting a few years ago in Chicago, and also a featured speaker at our last “live” meeting in Boston.

Bill, I met Costa Manos in both Chicago and Boston and found him to be a charming man. He was also an excellent speaker when it came to describing his work and imparting knowledge about photography and is techniques. Jim Lager showed us photographs of Eisenstaedt which he took when he visited his apartment to take shots of the great man using his Leicas. Eisenstaedt had taken a lovely photo many years earlier of the great Irish writer George Bernard Shaw using a Leica.

At our gallery here in Dublin we have just finished an exhibition by another Magnum photographer Martin Parr. In my recent talk on the history of photography in Ireland, I showed a shot which Henri Cartier Bresson took of a nun (a French order, of course) in St Stephens Green Park in the centre of Dublin. He captured a scene I saw many times as my father often brought me into that park on Sundays at around the time that HCB was here. I would recommend the ‘Magnum Ireland’ book to all LHSA members who are thinking of coming to Ireland for next year’s AGM. It features many of the great Magnum photographers, particularly Elliott Erwitt. Although when I met Erwitt in Wetzlar some years ago and said I was from Ireland, he immediately told me that he had done advertising photography for Aer Lingus, the Irish airline, and did not mention his Magnum work.

Going back to Costa Manos he has a great story about how he drove from Greece to Paris, not only to deliver his photos to Magnum, but also to escape being conscripted in Greece- he had been born in the US, but had Greek ancestry. When he got back to Greece he went up into the mountains, but the letter from Magnum accepting him into the agency found him in a remote village.

And finally, going back to your point about LIFE and other picture magazines we are lucky to have seen the height of the influence of such magazines and the photographers which they employed. It is not the same today with wall to wall digital images on social media. As compared to the work of a lot of today’s photographers, the work of Capa and Gerda will long be remembered, but I’m still not sure about that photo of the soldier being shot during the Spanish Civil War. Was that a form of ‘biofiction’?

William

I guess many would have read Richard Whelan’s “This Is War! Robert Capa At Work”. He writes the allegation that Capa staged the Falling Soldier forced him to undertake a “fantastic amount of research” that spanned twenty years. If one has the book, he begins his argument on page 54.

There is something of a ‘Capa industry’. The ‘drying accident’ of the D-Day photos is also probably worthy of study. At least there are no Photoshop or Lightroom aspects of those stories for people to witter on about!

William

Dear Bill,

I fully understand you. I had my struggles with this book at first, too. But maybe my review motivated you to give it another try? It might, if this is possible at all after all you already know and did, widen your horizon of the Magnum context.

I am very glad that there so many knowledgeable persons to work with the heritage of these great photographers! In Germany, we have the “Stern”, an illustrated magazine. It had an excellent reputation for photojournalism, but there is not much left of this legacy due to the saddening decline in the value of good photographs (and, as a consequence, the medium of photography). Add to this the mystification of Capa et al., and you get an idea of how fast and how profoundly things are a-changing. JP

It is one of the side effects of the digital era. A lot more photos, but fewer that can be regarded as great. Also the value of printed and published photos has declined. The latest horror on the horizon is crypto art with photographic images becoming NFTs (non fungible tokens) and a bubble market aligned with that of crypto currencies. All of this dilutes the value of the traditional photographic image. That is why we should value the work of the likes of Taro and Capa and others of their era. The golden period of photography is in the past, it seems.

William

Great review, Joerg-Peter, for what was probably a difficult book to read, let alone review. Is there a category for books like this eg it is ‘fiction’ or faction’, mixing reality with creative writing? The difficulty often is that such works then cause myth and reality to be confused in people’s minds. I suppose that after 80 to 90 years the stories about famous creative people have grown anyway, even if such a book was not written. Then things like the ‘Mexican Suitcase’ add to the mythology.

The 1930s through to the 1960s probably represent a highpoint for documentary photography. Not only did photographers now have equipment which enabled them to photograph dramatic events ‘on the hoof’, their photographs were often the only way that people could see what was going on in the world. Then we had television and we could see events as they happened and then digital media happened and now a very large proportion of the world’s population has cameras with communications functions in their pockets. We are about to have the Prix Pictet short list exhibited in our gallery in Dublin, but what I see there is more like creating art from areas of conflict rather than reportage which is what Taro and Capa did in the 1930s. I’m not saying that one is better than the other, but the medium has changed with the different times in which we have lived. Taro and Capa and countless others were very brave in what they did and without their selfless sacrifices we would know a lot less about what went on in their time.

As for the camera and lens, I usually pay no attention to what cameras photographers have used as it is the photographs that we must judge and not the cameras. For what it is worth, though, Gerda is shown using a Leica III (could have been a IIIa, detail is not sufficient), the strap is a giveaway as the II did not have lugs, with a Leitz 5cm f2 Summar.

William

It’s biofiction, William, and a genre I like very much.

Thanks Mike, that is my new word for today. It takes a skilled writer, though, to really succeed with this genre. No matter how often you explain, the melange between fact and fiction can lead to unintended mythology.

William

Hi Mike

also known as post modern literature?

here is one from the state i am from in India… quite a good translation actually. i remember reading it in its original form – Tamil – it was an exhilarating ride !!

https://www.amazon.in/Zero-Degree-Charu-Nivedita-ebook/dp/B0798PT2H3/r

Best

Kannan

Thanks, I will take a look. It will be something different…

Dear William,

thank very much you for your feedback. First, I am happy to see that my assumption about the camera shown in the Wikipedia image was more ore less correct. I ususally do not pay much attention to such questions, but the very book title triggered my curiosity. As I just wrote in my reply to David B, the name Leica in the book title will have the one or the other reason. There is no proof that Gerda Taro was a dedicated Leica photographer but to be honest, for her position in the history of photography it matters in no way which camera she used… except from the fact that it was a small camera that allowed for a different technique of image-taking.

I could not agree more to your points concerning the changes within and around photography. For me, the 30s to the early 70s were an era of its own, and the photographers from that time are more my role models than those of the generation after. I had the honour of opening an exhibition of pictures by Werner Bischof at the Leica Galerie Konstanz. His pictures from post-war Germany are simply outstanding.

I think the changes that the medium of photography is currently undergoing are almost inevitable. Documentary photographs are now available in inflationary numbers, and the increasing automation of the photographic process, right up to artificial intelligence, has robbed the artisanal process of any exclusivity. It’s a bit like when photography challenged (yet never replaced?) the medium of painting in the 19th century. It – arguably – triggered the biggest changes in the theory and practice of painting since the Renaissance era.

So it’s an almost natural development from an art-historical perspective. Documentary photography is largely exhausted and has most recently asserted its significance primarily through the subject matters (something like the Bechers’ colliery towers). I am curious to see what happens next. On 1 October, I will open another exhibition here in Constance with an exciting photographer. His name is Tom Hegen, he is very young, and with his artistic aerial photographs he walks exactly the same line that you, William, describe. I will ask him for his opinion on the topic discussed here and I am curious what he thinks.

It’s a big topic (“ein weites Feld”, as Theodor Fontane’s great novel “Effi Briest” says), we can’t close it here. But maybe one of us would like to write something bigger about it here for Macfilos?

Best, Jörg-Peter

.

I have a huge, thick, illustrated (..non-fiction..) shiny, heavy book about Gerda Taro on the top of the bookshelf, and now you’ve just prompted me to hoist it down (..can one hoist down as well as up?..) and to open its covers and read more about her life ..thank you!

So after lunch I’ll get it down and let you know what it says about her cameras!

– David.

..having got to page 234 – the last page of “Gerda Taro – Inventing Robert Capa” by Jane Rogoyska – I’ve found only two photos ..of hundreds!.. which show her with a Leica, and it’s thought that in 1937 when Capa changed from a Leica to a Contax (..with its easier ‘one-window’ focusing..) and Gerda gave up using her Rolleiflex, that it was his no-longer-needed Leica which she began using.

“..Whatever happened to Taro’s camera I did not find out. Was it destroyed in the fatal accident? Did Robert Capa use it afterward? Did it remain in Spain, Paris, the United States?..”

It’s generally believed that it was indeed “..destroyed in the fatal accident..” when she was run over by a tank, and that, as she often carried the Eyemo movie camera – lent to Capa to shoot footage for ‘The March of Time’ – the movie camera was also destroyed in the same accident ..and so no final stills frames, nor movie frames, exist, nor the cameras which shot them.

Thank you very much, David, for providing this information. I knew that there were some more books published on Gerda Taro but I never read one of these. As to Gerda’s camera(s) – I tried to suggest that perhaps the name Leica also came into the book title for marketing reasons. Well, it does not really matter as this is definitely no book about Leicas (fair enought as it never claims to be one). And it is a good read in any case. Around Capa’s work many questions are still unresolved as we all know, think only of the discussions concerning the “Falling Soldier”. So we might see some more books and in some of them Gerda Taro hopefully plays a role, too. Best wishes, JP