Photography can often be described as a journey, and this is the story of a 91-year journey for a Leica III that had been forgotten and left behind by time. I feel like I’ve been away from photography for a while. Like most people these days, the general state of the universe has got me down. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not on the breadline, and I’ve still been taking photos, but I’ve just not been feeling it. Since COVID-19, it’s been a time of frustration for many people, as we watch the fat cats get fatter, and the rest of us are mostly bewildered by our ever decreasing bank balances.

It’s a strange world we live in, and I think that’s why most of us here hold a camera in our hands and wish we could be transported back to a happier time. Perhaps to a time seen through rose-tinted glasses, on black and white film.

The eternal search and the eternal journey

In common with many photographers, I am constantly looking for the next camera that will make me complete. I own many, and none have them has turned me into a David Bailey (Olympus mju) or a Don McCullin (Nikon F). I’ve got a couple of Rolleiflexes, but I am certainly no Vivian Meier. But if I had been born in an earlier time, where the airfare was cheap and the world was my proverbial oyster? Who knows?

Because of these dreams, I think the one camera that sits at the pinnacle of most people’s wish list is the Leitz-made Barnack Leica III. A purely mechanical little beauty. I’m not in any way a Leica fanboy. I’ve owned a few in the past and have always found them a bit fiddly and slow. Despite this, I’ve been delighted with the admiring glances you get from passers-by, but It’s never meant that I would keep one for any length of time. They always sell so well; therefore, I’m happy to keep looking and buying if I can buy one for the right price.

Spare or repair?

So, this brings me to the subject of my story.

One night, as I’m trawling through the thousands of “worked 40 years ago — excellent condition” film cameras on eBay, I spot a very sad-looking spares or repair Leica III, circa 1935. It’s a reasonable price. It’s black. I’m interested — for the right price, of course. It’s battered, but that doesn’t bother me. It’s not working. Again, it doesn’t bother me, as I have a guy who can fix almost anything.

Lost identity

The one thing that concerned me was the defaced serial number on the top plate, so I sent a screenshot to my camera guy (Rob) and immediately he said it was a fake, and advised me not to buy it. I really wasn’t so sure. Normally I would follow his advice as he has more experience than me, but it just looked right and had the slow shutter speed dial. I was pretty sure this was not a part of the Russian trickery on the faked ones I had seen in the past. It also just didn’t look faked. It wasn’t over the top. There was no fascist insignia or other such obvious tricks to lure the gullible.

After a bit of bartering, it was mine. I did a bit of research and found that serial numbers were sometimes defaced when a soldier had bartered with the German owner for a packet of cigarettes or loaf of bread. It could also have been stolen, and the serial number destroyed, so the rightful owner couldn’t be found. Whatever the story, I’m sure it stemmed from hardship during and after World War II. If only we knew what photos it had taken. Then again, maybe it’s better to let the past stay where it is. The one bit of good news was that the serial number was also stamped inside the top plate, so all was not lost.

Behind the brass

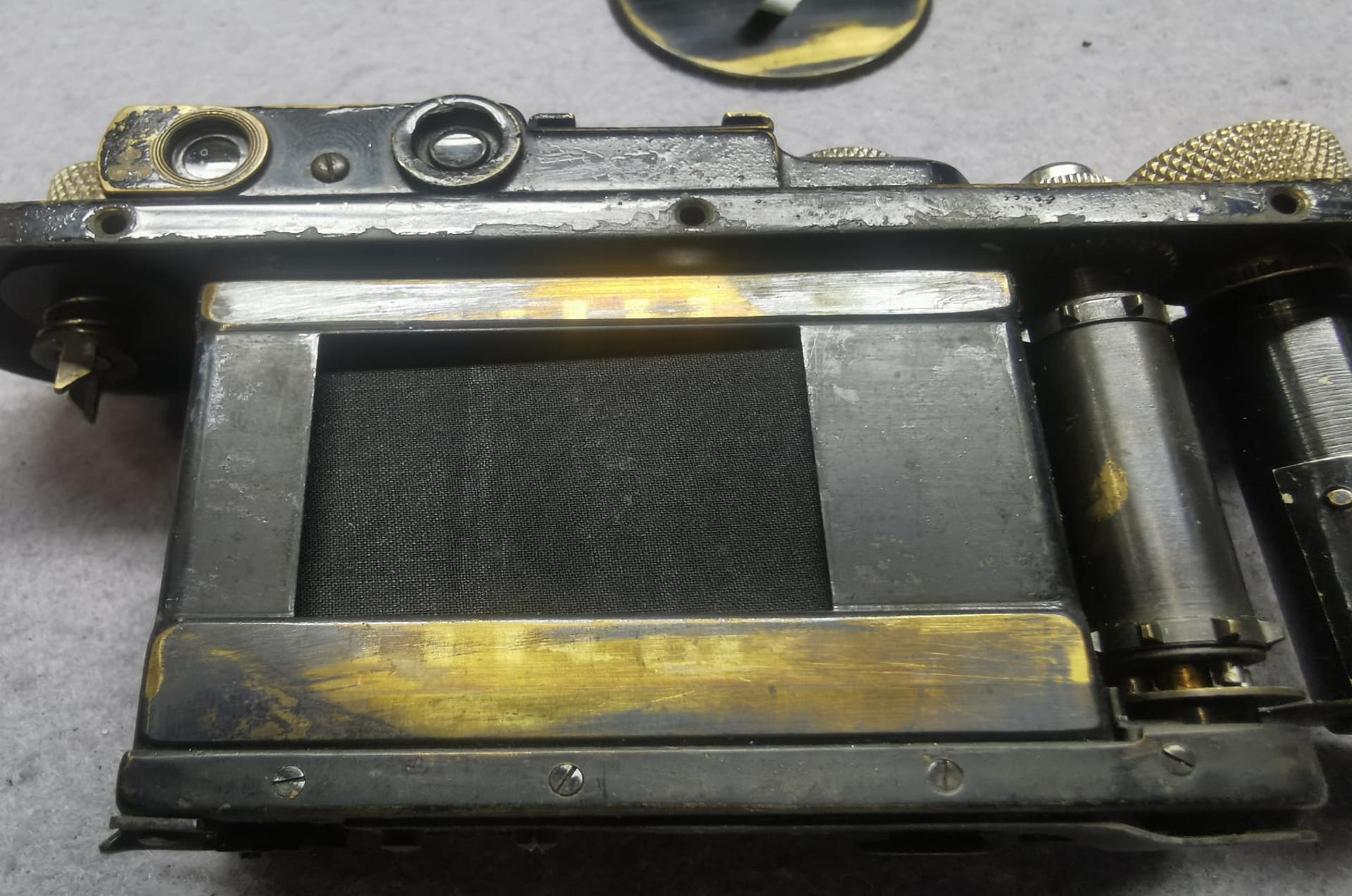

The camera arrived, and the photos on the listing really hadn’t done it justice. This device has had a lot of use. The black paint was worn through to the brass, just about everywhere. There was what looked like secondary black paint that maybe had been an attempt to conceal the wear, or was it that it had originally been a silver version painted black at a later date.

So many questions, but the main thing was that it wound OK, and the faster shutter speeds worked. Rather than send it straight off for a service, I decided to do what a camera does best, and stick a roll of Ilford HP5 in it and see if the old girl still had it in her.

I’m afraid to say that the results weren’t good. After a day walking around Birmingham with a bag full of cameras, I was surprised that mechanically the camera worked really well. However, the photos it produced were another matter.

They gave the impression I’d been shooting in Hell, and this is no reflection on the lovely city that the Brummies’ call home. I knew that this wasn’t a developing error, as I had sent them to AG Photolabs and had never had a problem with the negatives from them before.

The Matrix unexpectedly appears

Some images were fine, but then others looked like they had the mother of all light leaks. It seemed that there was a bleed from the right-hand side of the film. Either that or I had entered the Matrix. Very strange. Off it went to Rob at Vintage Cameras Galore for a service and the search for the serial number.

The hidden identity

Now, this is where the story gets very interesting.

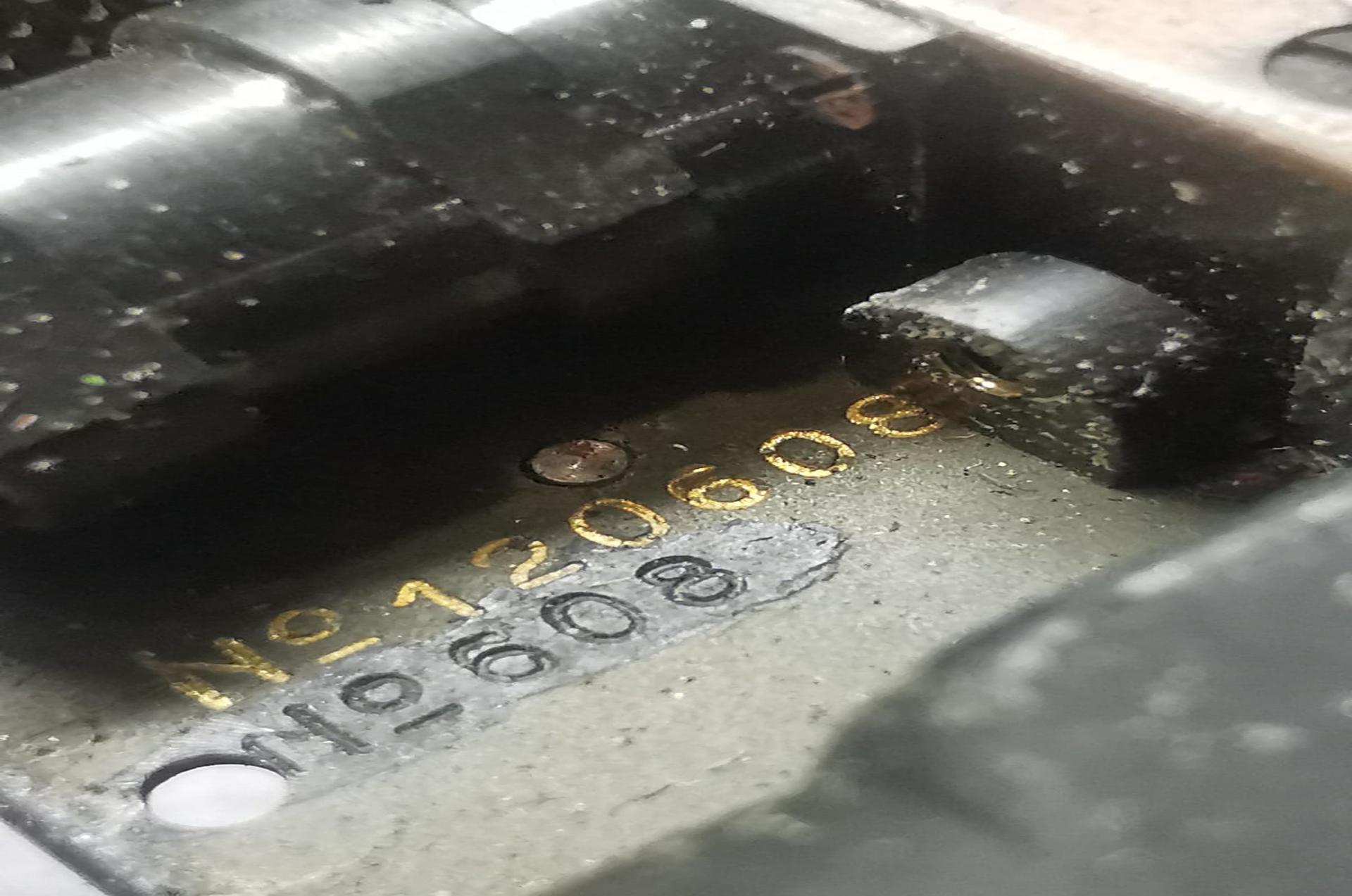

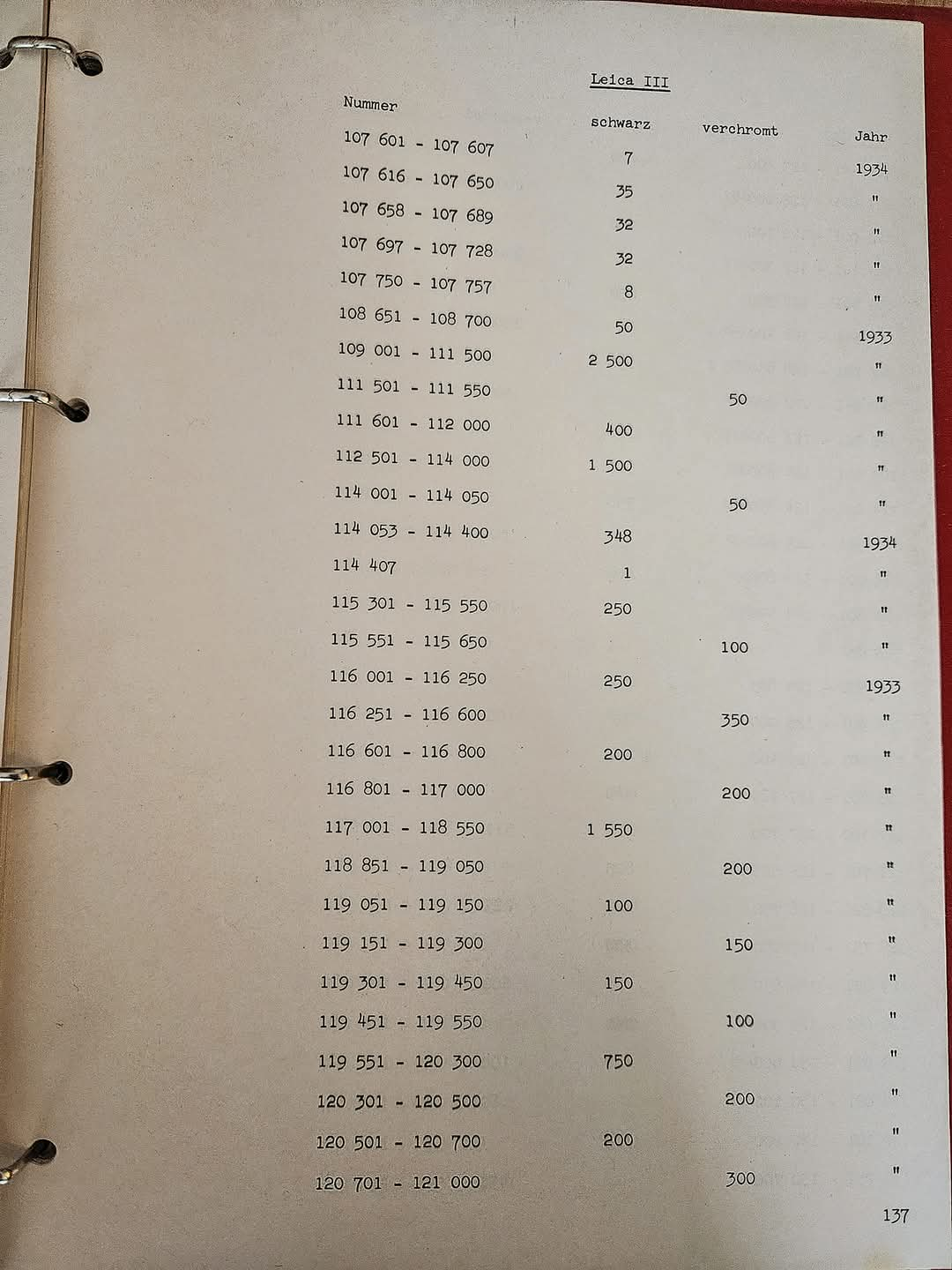

Rob takes the camera apart and gives me the news I was hoping for, that it’s definitely a Leica. Thank God for that. Next he sends me photos of the serial number which is stamped underneath the top plate. The number is 120608. This makes it a Leica III made in 1933, earlier than first thought.

Now, that throws up more questions as, when looking on the internet, this was from a batch of chrome bodied cameras to leave the Leica factory. Red Book Was it a later repaint, as I had previously thought. Initially, Rob believed the answer was yes, but after taking off the messy top coat, he announced that it had always been a black bodied camera as there was no chrome present at all. The plot thickens.

The history of a 91-year journey revealed

I put the photos I had onto the Leica Facebook group, to see if anyone could shed light on the anomalies we’d found. People agreed with me that the serial number was probably defaced after World War II, for whatever reason, most likely as it was looted or taken as spoils of war. Then a very interesting comment was posted by a German Leica enthusiast. For privacy reasons, I won’t post the screenshot I have or his name.

“It was a Luftwaffe Eigentum Leica.”

“The Number 120608, my old friend Herman (he died 1990) was a Leica mechanician 1935-40. He had a list of Wehrmacht cameras”.

When I pushed him for more information, unfortunately he had none. If only I could get hold of that list. What a read that would be.

Anyway, back to my now, in pieces, Leica III. Rob said he’d never seen a camera with as much wear. Did I want him to do a full refurb? Not a chance. It’s old and battered, just like me, and I’m happy to keep it this way.

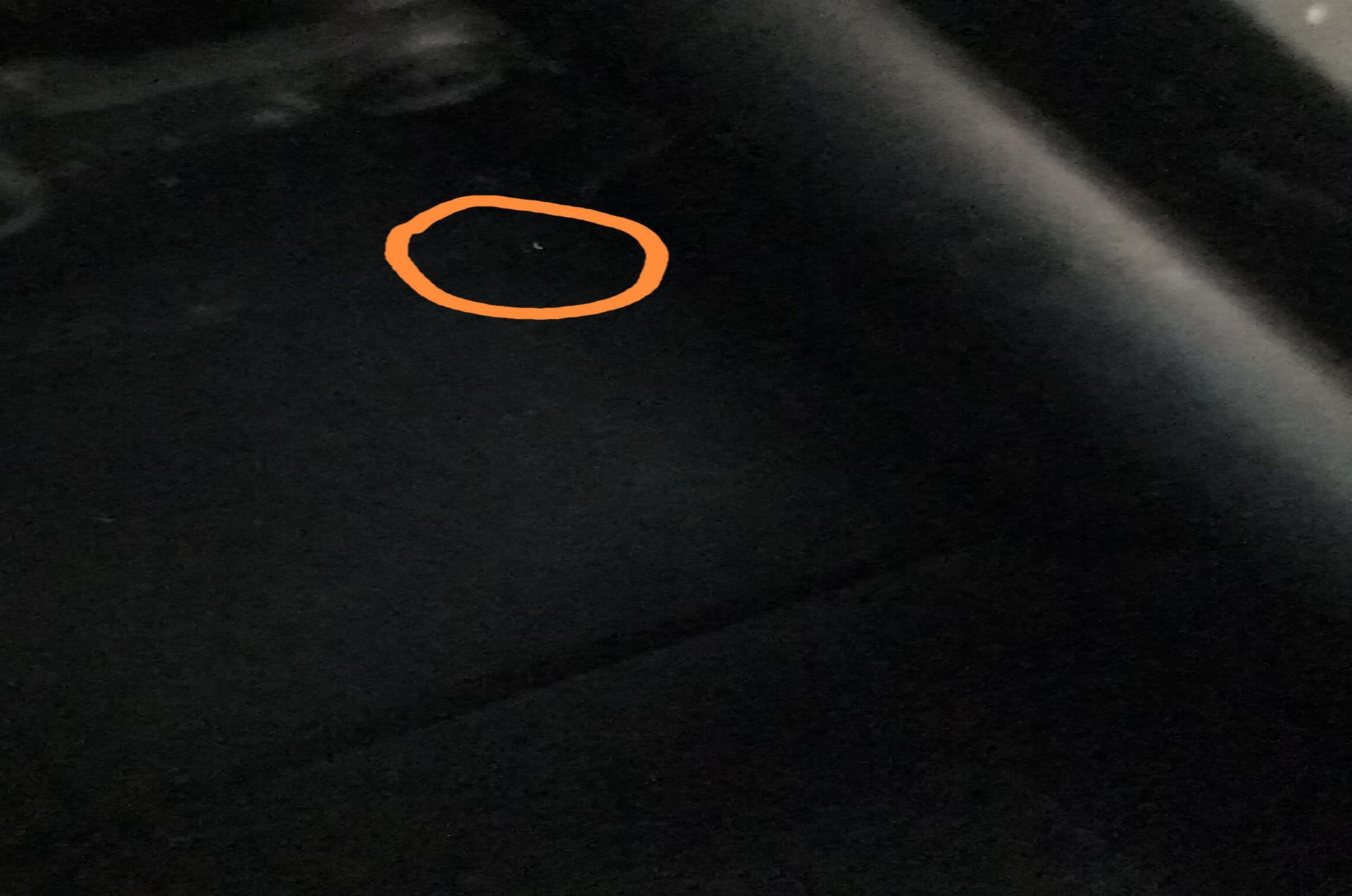

Finding the black hole

He repainted the film gate, which, in his words, had had a sh*t load of film through it. More worryingly, he couldn’t locate the source of the light leak. He said the shutter curtains were in surprisingly good condition. Then late one night, I get a frantic WhatsApp message from him with a photo that initially just looks like a black screen.

“Can you see it?” he excitedly asks. “What?” I respond, half asleep. It turns out there is the tiniest of holes in the curtain. He’s been up all night trying to find it and finally saw that minute pinprick of light. It appears that this, coupled with the shiny surface of the worn film gate, was what had caused the light leaks and my descent into the Matrix.

Happy that it seemed all was well, I emailed Leica with all the information I had, hoping that they could shed some light on the early history of my camera. What they came up with was a little disappointing, but still nice to know.

The journey from Wetzlar to here

Leica III with the serial number 120608 left the Leitz factory on 14th November 1933 and its destination was… London. Unfortunately, no more details were found, including the recipient. When asked about the colour difference, I was told it happened in the early days that a camera was customised for a particular customer. So that was it.

Unless anyone knows better, my little Leica was shipped to London in 1933, destination unknown. Certainly makes the Luftwaffe link tenuous, but I suppose it could have gone to the German Embassy, as relations were still cordial in ’33. More than likely, however, it was a normal commercial transaction, and it was consigned to the Leitz HQ in Mortimer Street, London. From there it would have gone out to one of the many Leica dealers in the UK.

On the other hand, does it really matter that I don’t know its original recipient? I gaze at the beautiful brassing to the body and look at the photos of the film gate and know that this camera has had a hell of a life. It has truly lived, and even though I know no more than its birthday and where it was first held by its new owner, I know that this camera has lived.

Should it stay or should it go?

So, it was back in my hands. What would I do with it? I am a trader. I sell film cameras. This is a film camera. But could I let it go? Of course, everything has a price, and the answer is yes if someone offers me a gazillion dollars.

As I always do before offering a camera for sale, I loaded it with Ilford HP5 and set off to find something interesting to shoot. Near to me is a marina and canal, so with the sun shining on my back, off I went. I snapped away at all the happy people and colourful boats in the late autumn sunshine.

I met an old boy who was an ex-RAF photographer who asked if he could have a look at the Leica. He was blown away by the history of the little Leica. This is the one thing I love about film photography, you meet some lovely people. After a bit of effort, I managed to prise the camera out of his hands. I politely told him that if he had a gazillion dollars, he could keep it. He wiped away a tear and said that he didn’t, so I went home to develop the film.

When the film goes MIA

I’ve started to develop my own black and white film again. Not because I enjoy it, but because I’m too tight to pay someone else to do it. I am normally pretty good at it, and of course because this was an important film from a special camera, I completely cocked it up. I really am too embarrassed to tell you that I loaded the film onto the reel, got side-tracked, opened the bag up and took the Patterson tank out. Then thought, “Hold on, did I put the film in?”. The answer was no.

Needless to say, the film was pretty fogged when I eventually took it out to dry. I scanned with my Epson v600, and there were a couple of good images, but the main thing was that there were no light leaks. The images were nice and contrasty, as sharp as they ever need to be from a geriatric lens. How can a 91-year-old camera and a 89-year-old lens work so well? It’s like the worst double act in history, but it shows what a special little package the Leica III was when it left the Leitz factory in Wetzlar, 91 years ago, and started on a 500-mile journey to its new home in Britain.

And here’s to the next 90 years

The story of what happened to the little Leica in the proceeding 91 years is a mystery. How it came into my hands is pure chance. Will someone else be adding to its story in the near future? Only if they have a Gazillion Dollars.

UPDATE: It has been confirmed by Michael Baumeister that the camera left Leitz as a batch of 200 black bodies. This came from the “Hahne List”, published by the Leica Historica Society.

A big thank you to the following for their help and professionalism:

This article was first published on 35mmc.

More on the Leica III on Macfilos

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Thanks, Chris, for this wonderful article. I hope you can add to the history of this veteran and use it for years to come. And one day it will go into the hands of the next owner who will or will not do his or her own research on this particular camera. Most important thing is that it being used? Cheers, Jörg-Peter

Thanks Jorg-Peter, thank you for taking the time to read my article. I’m hoping that it isn’t the end of the story and more history will be revealed. I have just bought another black-body Leica iii from 1933 that also has the serial number defaced. The detective in me feels there’s a reason why these cameras have been left this way

I don’t know who loves LEICA more u or Mr Fagan! Just so fascinating the devotion u both show your leicas. Thank you keeping history alive!

Thanks John. I am a mere amateur compared to Mr Fagan, but thank you for the complement. I think the history of the camera that we hold in our hands is part of the reason that we keep putting our faith in film. Happy New Year

Thanks Chris for a cracking story. A beautiful camera.

Thank you Jean for reading the article and taking the time to comment. Happy New Year to you

Thanks Chris,

This is a wonderful detective story and a cracking good read for those of us who don’t know the intricacies of Leica’s history.

Jon

Thanks Jon. I’ve since got hold of another 1933 Leica iii black-body with the serial number defaced. The Columbo is already on the case to find out why?

Happy New Year to you

Very interesting that you achieved such a good photo of the narrowboat with such an old camera and lens. A fascinating story, thank you.

Thanks Kevin. The photo is certainly not the greatest I’ve taken but shows how useable these cameras are. We’ve come along way since 1933 but it just goes to show that Oscar Barnack certainly knew what he was doing.

Happy New Year to you

Chris, we communicated about this a few weeks ago. Looking at the extract from the Hahne list, 120608 is from the batch of 200 black (schwarz) cameras 120501 – 120700, so, if the Hahne list is correct, this camera ‘should’ have been black, as you now point out. This camera may indeed have been used by a military person during WWII, but the most authoritative list on the wartime delivery of German military Leicas is that done by Dr Luigi Cane (with assistance by Lars Netopil) for the German Leica Historica Society. The earliest serial number in that is 315353. If this camera was delivered to Britain it might have ended up on the Allied side after the requests by the RAF and others to donate cameras.

The camera has a nice patina and I have seen Black Paint M3s in similar condition selling for ridiculous sums, but the ‘Black Paint Fetish’ does not really extend to prewar cameras. These days, prewar black paint cameras sell for a slight premium, but in 1933 a chrome camera would have been more expensive than a black paint one.

Properly serviced, there should be no limit to the life of these cameras. I have shown photos from a couple of I Model As from 1926 in two separate articles on Macfilos and in one case we had fun asking people which photos were from the 1926 camera and which were from a 2017 M10. In one of those cases the shims (for focus distance) behind the lens mount of one of I Model As (No 1661) fell out as I was using it and I had to repair it ‘on the hoof’. I still got nice photos after the ‘running repair’.

I know that your ‘inner dealer’ hopes that the camera might have some value out of the ordinary. Maybe some more information as regards its provenance might come out of the woodwork, but in the meantime you should regard is as a remarkable artefact that is still able to do its job, as intended, at the age of 91.

Lovely article and great photos.

William

Thanks William for taking the time to comment. I feel like there is a story why the serial number is defaced. I have discussed this with Michael Baumeister (who provided me with the Hahne list info). I realise that after the war, items were traded and the camera could have been a “spoil of war”. However, as it was shipped to London, it seems unlikely.

The story now continues as I have just bought another 1933 black body that also has the serial number defaced. I am waiting to hear from Leica concerning where this body was shipped to. If there is a link between the two, the Columbo in me will be on the case.

Happy New Year

Great story – I have only taken notice of Leica cameras in general for the past year or two but it is this unique history of the brand that has fascinated me from the start. Hope you’ll take some great photos with it.

Thanks for reading the article Andrew. I have tried to stay away from the lure of Leica for as long as I can, but its hard when they have the accessible history and stories that come with them. Its also hard to get away from the fact that they are so damn good to use.

Happy New Year