Most photography and camera enthusiasts know that ‘Leica’ is a concatenation of ‘LEItz’ and ‘CAmera’. The marque has a long history and, indeed, prehistory which certainly can be called a heritage. Even the uninitiated will recognise the similarities between a Leica I from 1925 and a Leica M11 from 2025, but the heritage goes much deeper than that.

Leica Heritage: And in the beginning…

To begin at the beginning, to quote Dylan Thomas and several others, the firm that was to become Ernst Leitz, was founded in Wetzlar in 1849, exactly 100 years before I was born, by a very young man called Carl Kellner. This was called the Optisches Institut (Optical Institute) and its main business was the production of lenses and microscopes.

Kellner died at the age of 29 in 1855. In 1864, a precision mechanic named Ernst Leitz joined the firm and eventually took it over in 1869 when it was renamed Ernst Leitz GmbH.

The firm continued producing microscopes and precision optics for many years, and from the 1880s onwards it produced some microphotographic and macrophotographic cameras for use with its microscopes.

In the early 1900s Leitz started to sell ‘normal’ cameras with bodies for large format photography, such as this Moment 12×18 cm format camera from 1907 with a body by Kruegnener and a Leitz Summar 180mm lens in a Bausch & Lomb shutter

Oskar Barnack arrives

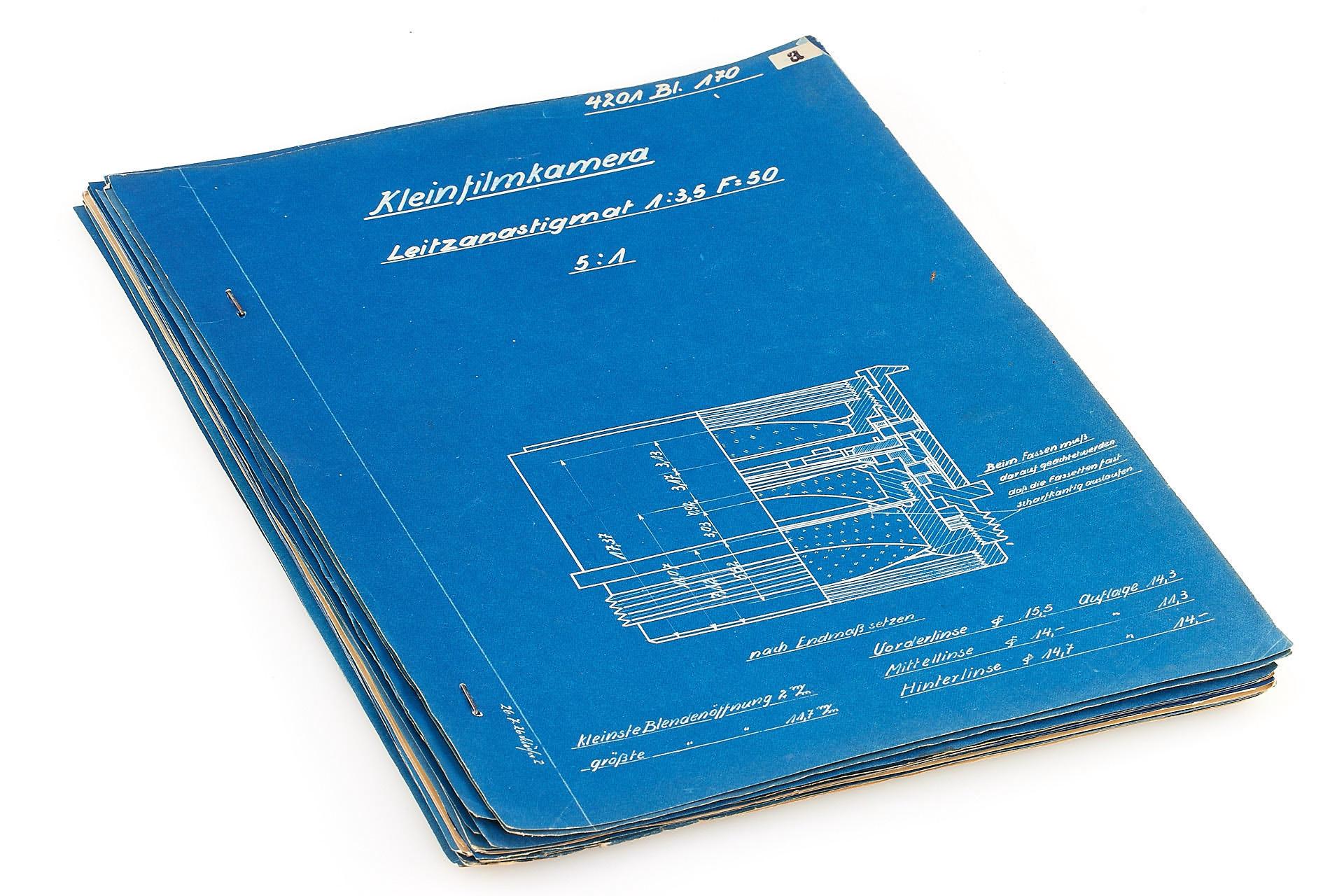

The heritage of the Optical Institute remained, as the lens was by Leitz, but at that stage Leitz was not really a producer of cameras. In 1911, a young mechanic, named Oskar Barnack, joined the Leitz firm. One of his first jobs was to work on this large and heavy 35mm cine camera.

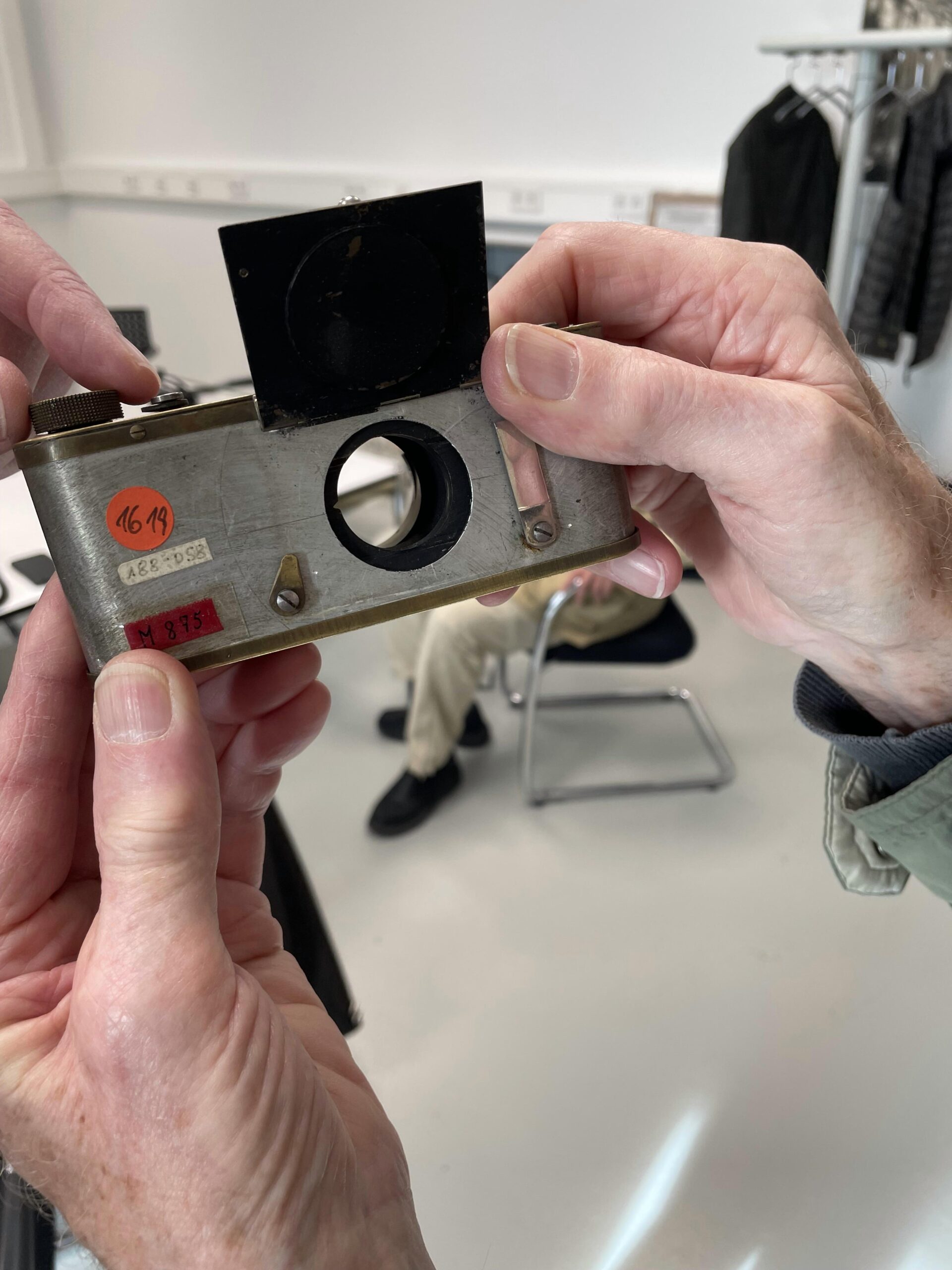

At around the same time, Barnack created a 35mm film testing device, now designated in the Leica Archive as M 875, which has a very familiar shape, now truly part of the Leica heritage.

It has a guillotine shutter which operates at about 1/40th of a second, which matches the frame rate of the cine camera. In addition, it has a hole at the back which could mean that it also functioned as a ‘graphoscope’ viewer of negatives in the same way as the Kemper Kombi, one of the first all metal cameras from the 1890s.

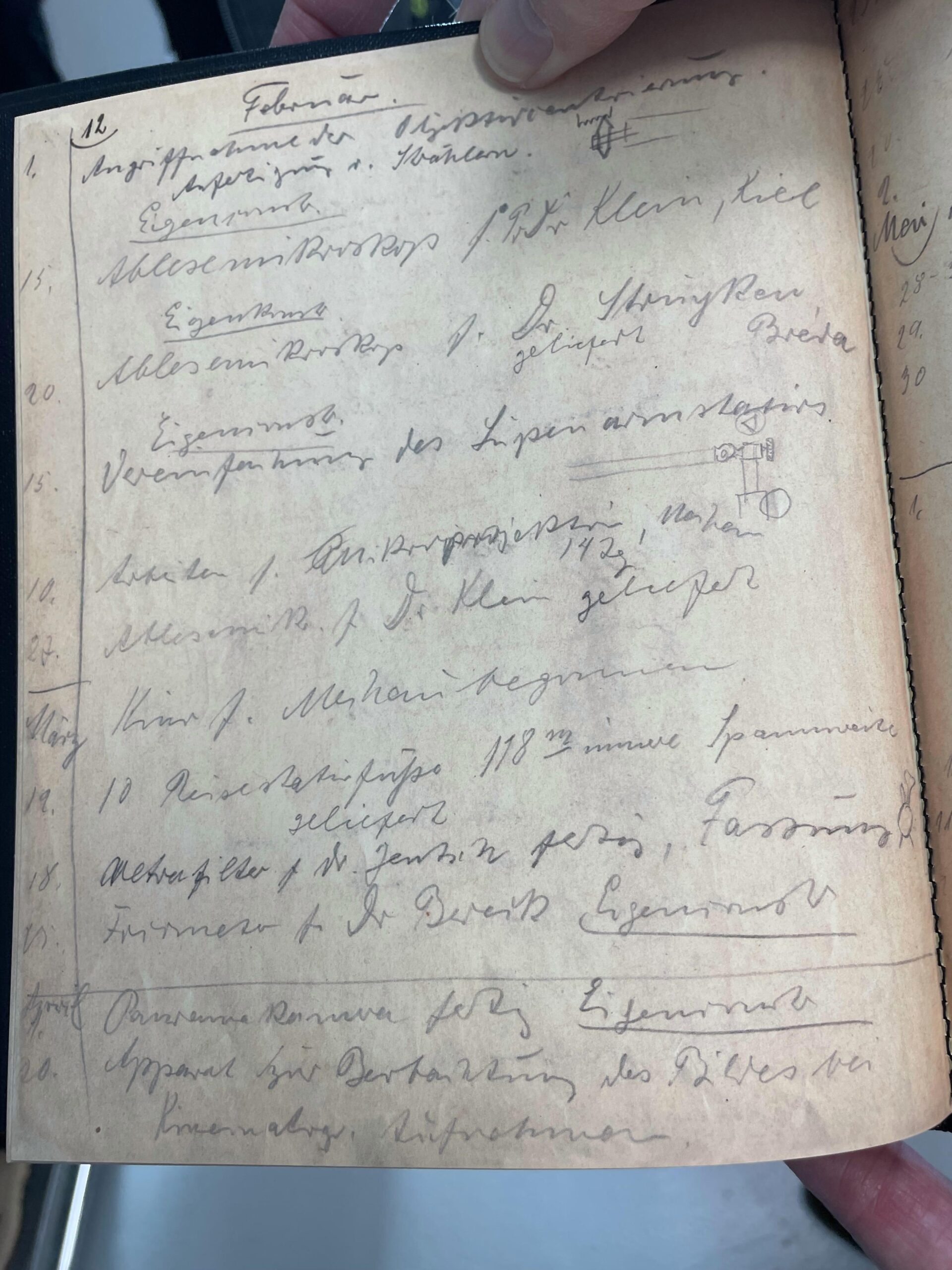

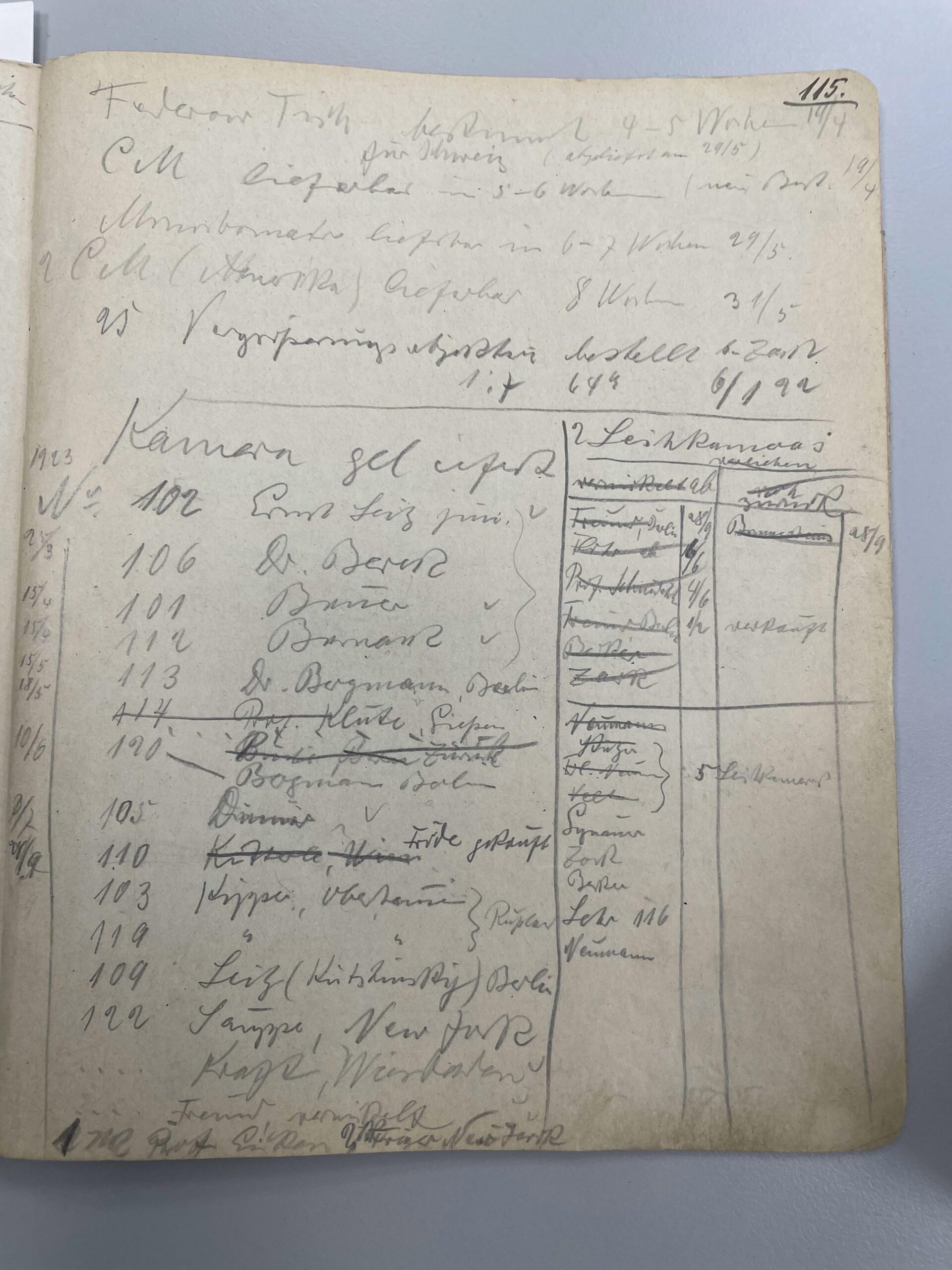

Despite much debate about how this device worked and even examination of Barnack’s own notebook (sample page shown below) we are still not 100% sure as to how this was used. But it is part of the Leitz/Leica heritage, perhaps the first appearance of that famous shape.

My view is that it was used both for testing 35mm film samples before use in the cine camera and for viewing the quality of developed negatives afterwards.

The Ur-Leica

The next step was the Ur-Leica prototype 35mm camera of 1914, but we don’t have a clear line of development from M 875 apart from the tubular shape and the hole at the front which contained a lens.

Before going into the camera in more detail, it must be pointed out that there were about forty 35mm film cameras in existence from about 1905 to 1925. But apart, perhaps, from the French Furet cameras, which had a form factor similar to the Leica, very few were really successful.

With the Ur-Leica Barnack sought a 2×3 ratio, which resulted in a doubling of the width of the cine frame from 24×18mm to 24×36mm for 35mm film.

Initially, he looked at 38mm for 8 sprocket holes, but the image size for the Ur-Leica was found to be 24.8×36.8 mm when measured. 2×3 or 24×36mm is rightly regarded as part of the Leica heritage.

However, the American Simplex 35mm camera of 1914 (see list linked above) produced 24×36mm negatives. On the other hand, only 27 examples of that camera still exist, as compared to the Leica which achieved over 2,300 examples made by the end of 1926.

For what it’s worth, the Furet camera, introduced in 1923, had a frame size of 24×37.5mm. What Barnack did was logical, and others applied the same logic. But as the Leica was one of the great popularisers of the format, we must say that the 24×36mm, the so-called full-frame format, is definitely part of the Leica Heritage.

Nevertheless, the main difference between the Leica camera and the others mentioned is that it is still there today, honouring its heritage.

Leica Heritage: The focal plane shutter

‘Ur-Leica’ means ’Original Leica’ or even ‘Primitive Leica’. Let’s go through some of the features:

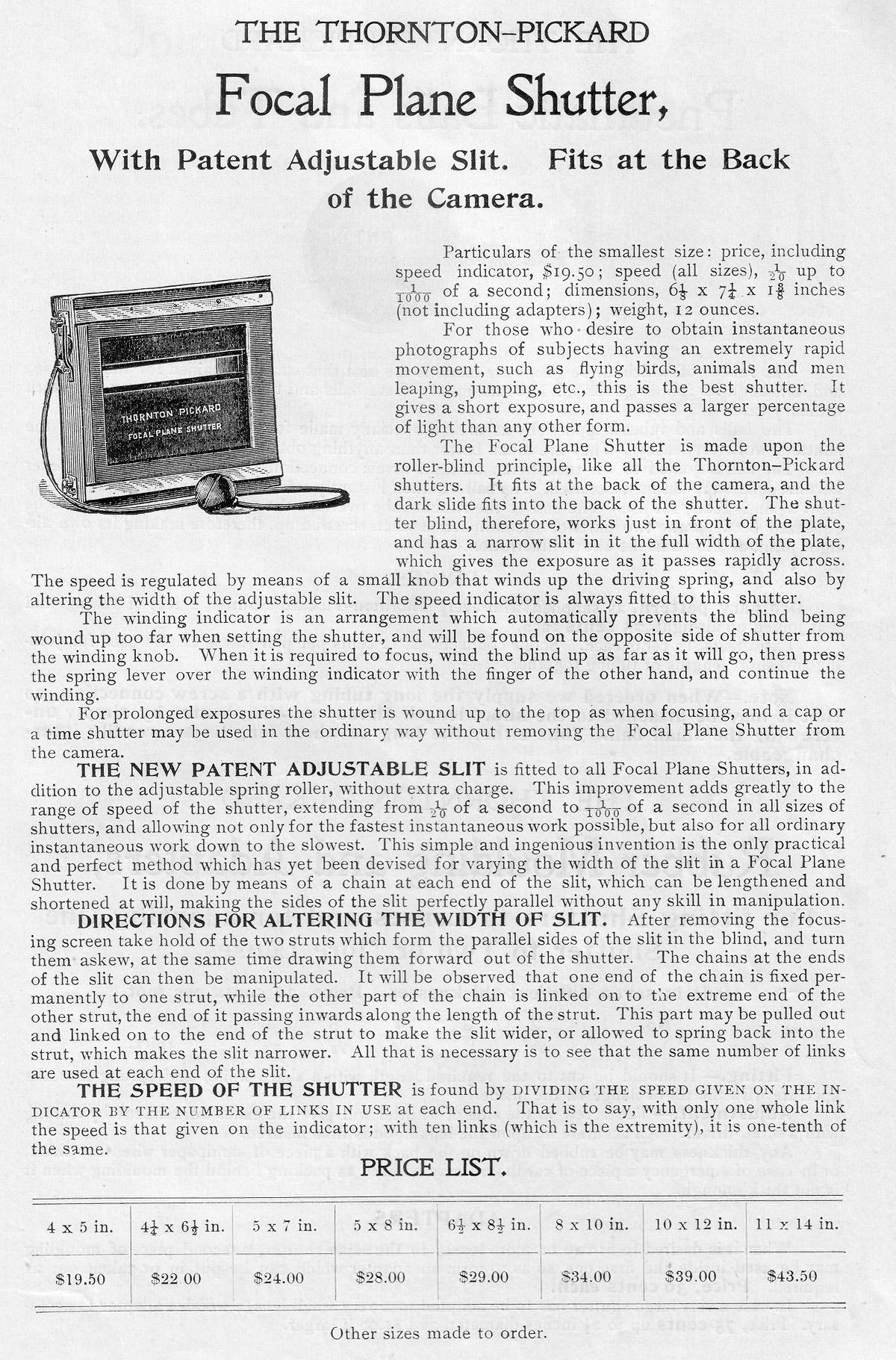

Focal Plane Shutter. This was not new, even in 1914. In the 1890s, Thornton Pickard sold focal plane shutters with speeds of up to 1/1000th of a second for traditional late 19th Century dry plate cameras.

In 1894, The Goerz company, which supplied glass to Leitz, launched the Goerz Anschutz Ango which also had a focal plane shutter, but like the Thornton Pickard, it had a complex system of speed controls and shutter cocking. The Ur-Leica combined wind on and shutter cocking in a single movement.

The Anschutz had helicoid focus which had not really been used before, apart from a few outliers such as Grubb in Ireland in the 1850s (see my Grubb and Parsons article). When Max Berek came to design his Anastigmat lens, around 1920, he used helicoid focus to achieve a small collapsible lens which could be easily focused. This type of helicoid is now almost universal in camera lenses which can be focused.

By 1914 most cameras had either bellows focus or a box shape, so the little independently focused lens at the front was quite novel.

Shutter speeds

The Ur-Leica used slit widths as did the pre-production 0 Series prototype cameras which had the following system:

Slit width in mm – fraction of a second = effective shutter speed

- 2 – 1/500s

- 5 – 1/200s

- 10 – 1/100s

- 20 -1/50s

- 50 – 1/25s

This, of course, reverses the situation with which we are familiar. Under this system, the higher the number, the slower the shutter speed, which reverses the cognitive approach which we have today.

Here are the slit widths on the Leica 0 Series camera in the same position as would be later occupied by a speed dial

Up to just before the production models, the Leitz cameras were not self-capping, and the lens cap had to be left on when winding as there was a slit between the first and second curtains.

Leica Heritage: The 0 Series

This camera was part of the legendary 0 series and the was later used by Barnack himself and then owned by his son. The 0 Series cameras were not sold, but they were distributed to friends and trusted associates for testing and were then returned to the factory for testing and sometimes were given out to another person for further testing. As this page from Barnack’s handwritten notebook shows, Barnack initially gave himself No.112 for testing.

No 112 will be auctioned at the 100th Birthday celebrations in Wetzlar in June and I will write further about it

The Leica was launched at the Leipzig Spring Fair in March 1925 as a camera without an interchangeable lens. However, the capped focal plane shutter with shutter speeds independently adjusted on the body gave rise to a clear possibility of interchangeable lenses.

The first attempts to do this were in Britain, where, for example, Sinclair, which was a Leica dealer, added the possibility of using British-made Dallmeyer lenses with the same 33mm mount as the I Model A.

As with the Elmar lenses on the Leica body, the lenses had to be matched with the body using shims behind the lens mount. They were confirmed using a ground glass screen held against the little hole (normally plugged) at the back of the camera. The matched lens and the camera body both carried the same serial number.

Leitz became aware of the British conversions and, within a year or so, it had introduced the Non-Standardised Leica I Model C with the then new and long-lasting 39mm screw mount.

Enter the M39 LTM

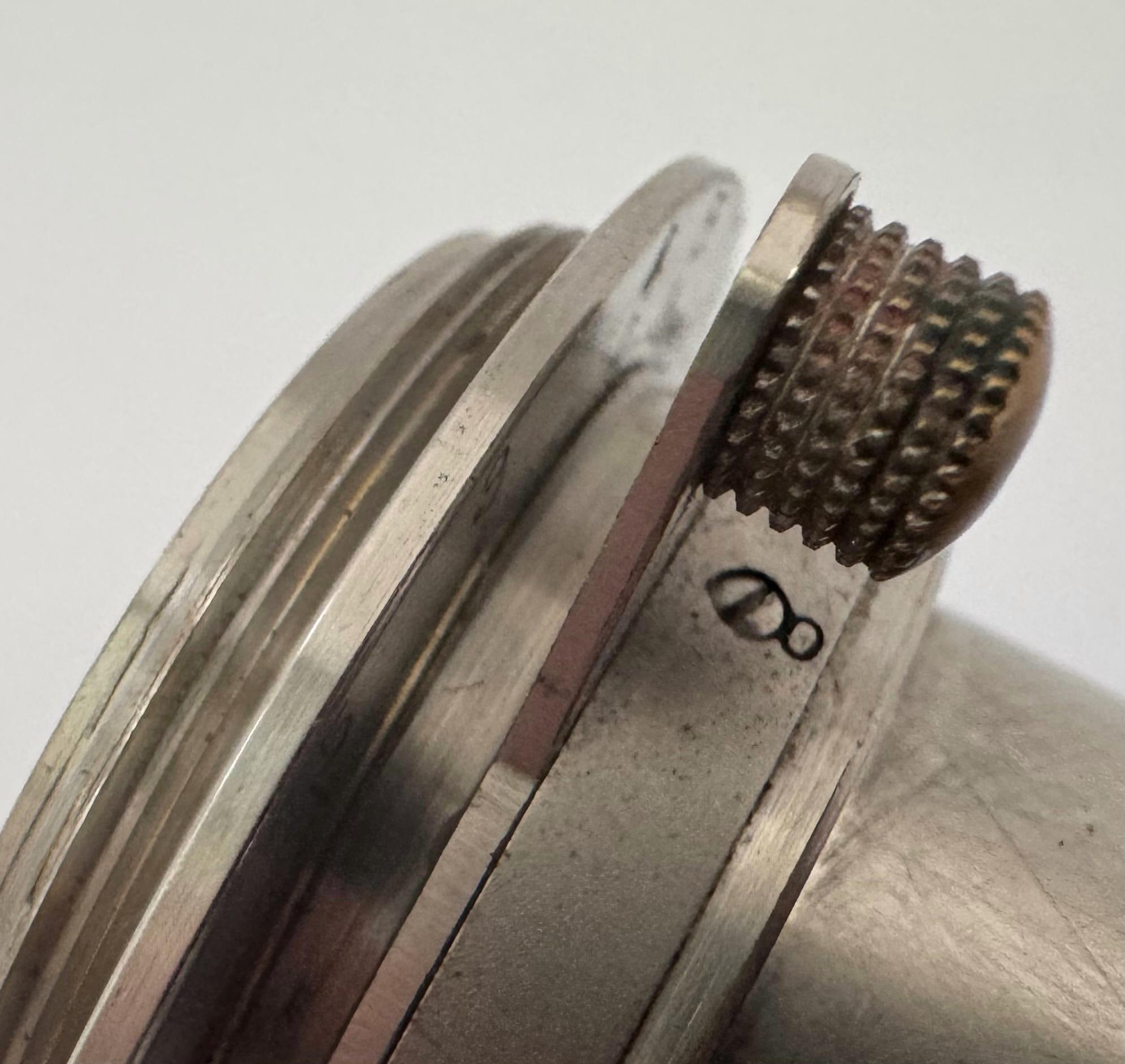

This became known as the M39 or Leica Thread Mount, or just LTM. These lenses had to be matched with the camera body and carried a number to indicate such matching, which was usually the last three digits from the camera serial number, which reflected the practice adopted for some British conversions.

The same could be done for several focal lengths, creating some of the first multi-lens kits outside of large format cameras

In 1931, the lens mounts were standardised with a standard distance of 28.8 mm from the flange to the film plane. The lens mounts on both the camera and the lens were marked with a ‘0’ to indicate that any lens so marked would fit any camera with the same mark.

In the 19th Century, lens interchangeability was possible by exchanging lenses which were attached to wooden boards, but this was a whole new dimension for lens interchangeability, made possible by the focal plane shutter and the standardised mount. Thus, another chapter in the Leica Heritage was created.

Automatic focus

In 1932 Leitz announced the introduction of the II Model D camera with ‘automatic focusing’ or ‘The Autofocal Camera’ i.e. a built-in rangefinder synced with the lens.

Before 1932, a separate rangefinder made by Leitz could be used, attached or unattached to the camera to give the correct distance to a subject, which had to be transferred separately to the lens. Leitz had been making such rangefinders for larger format cameras by other makers before it introduced its 35mm range.

The idea of a built-in rangefinder was not new, as Kodak had introduced the concept in 1917. However, that camera had a bellows which interacted with the rangefinder, but it only had lens choices and not interchangeable lenses. The Leitz solution worked with a range of coupled and standardised lenses, creating another stage in the Leica Heritage which holds good until the M11 of today.

The eagle-eyed will have spotted the basic Leica rangefinder camera shape, which has remained with us until today. Some people tend to refer to all the Leica mainstream cameras as ‘rangefinders’, but the true ‘Leica rangefinder camera’ did not appear until 1932.

Leica Heritage: Speed of development

Barnack was an inveterate improver of his creations, and other improvements followed in rapid succession. They were part of the Leica heritage, perhaps with a lower case ‘h’ as they were not as radical as the rangefinder addition in 1932.

- 1933: Slow speeds on a dial on the front of the camera and diopter control for the rangefinder window with the III

- 1935: 1,000th of a second with the IIIa

- 1938: Rangefinder and viewfinder windows closer together with the IIIb

- 1940: Diecast and slightly larger body with the IIIc

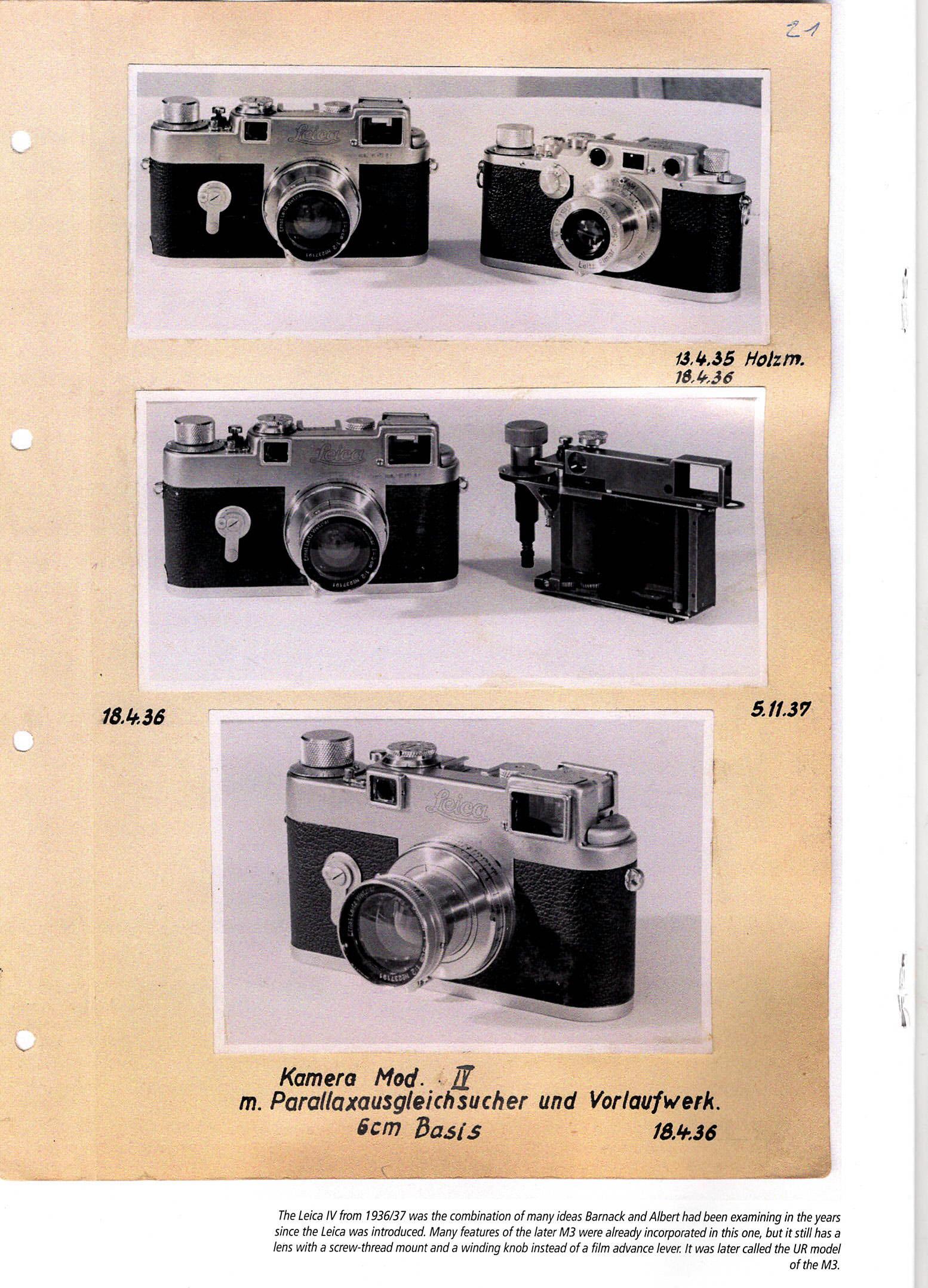

The next radical change happened with the Leica IV which had a combined rangefinder and viewfinder featuring interchangeable elements for different focal lengths instead of the frame lines which appeared in the M series in the 1950s. Barnack had been working on this with his assistant Wilhelm Albert before he died in January 1936. Albert later recorded the IV in his famous diary.

Future concepts

The IV, which had an LTM mount, never went into production, but it was an essential part of creating the Leica Heritage. It is yet another example of Barnack and his team working on ‘future concepts’ and testing them at length before introducing them to the marketplace, something which still happens today.

This is all related to what can be characterised as the ‘German engineering tradition’ which still holds sway in the company today. Engineering excellence has always been part of the Leitz/Leica tradition, and they have always worked hard at achieving this. Just a few minutes conversation with Stefan Daniel or Peter Karbe will show that this splendid tradition is still alive today.

This is a prototype of the Leica M from 1948, some six years before the M3 went on sale.

The Leica M

The next big step was the introduction of the M camera range in 1954. It is still with us today, over 70 years later. In common with many Leitz projects, the developments happened over many years and included the following, all prototyped in the 1930s:

- Combined rangefinder and viewfinder

- Rear Door

- Lever wind

Added to that were features such as a bayonet lens mount, frame lines for different focal lengths, self-timers and, on the M3, a covered frame counter with reset. Flash sync, which had recently been added to the f models, was also a feature.

The M3 was a remarkable camera when it was introduced in 1954, but what is even more remarkable is that the basic design is still in production some 71 years later.

The camera was introduced as a film camera, and it remained thus for over 50 years, over half the life span of the Leica camera. There was a some deviation in form factor in the early 1970s with the larger M5 and its exposure meter. But soon things soon got back on track with the M4-2.

The digital M

In 2006, Leica introduced the first major change, apart from the M5 excursion, with the introduction of the M8, which, in itself, was a remarkable feat.

This was the first M which was less than full frame with its APS-H 1.33 crop factor. Full frame came back with the M9 in 2009. Since then, there has been a steady stream of digital Ms, but they all contain the same basic features as regards focus and frame lines and the same basic shape as do the film Ms which are still in production.

Leica and the SLR

The LTM and M models can be said to be the ‘Leica Heritage Mainstream’ but Leica also dabbled with the Single Lens Reflex (SLR) design which could be said to have formed its own heritage line in the broader camera industry.

After the initial success of the Nikon F, Leica was slow to introduce its own Leicaflex SLR line, which was followed by the R line. These were all superb cameras, but alas they had more or less faded out by the time that SLRs went digital in the 2000s.

Such cameras constitute part of the Leica Heritage, but this strand was not as long-lasting as the LTM/M line. The same could, perhaps, be said of the many compact, bridge, and other off-mainstream types, sometimes with non-Leica heritage, which have appeared over many years.

Leica heritage: The Q series

Many of those cameras retained a similar form factor to the Leica mainstream. One recent example is the Leica Q3 43, which has a very familiar form factor and carries a lens with a focal length equal to that of the diagonal length on the original 24x 36mm frame size on the Leica I.

That Red Dot

One thing that might be noted above is the famous Red Dot, which some people still use to identify a Leica. On the other hand, we have people who tape up their red dots so that the camera they have will not be identified as a Leica.

Then you have another type of Leica fan who won’t buy a camera with a Red Dot and waits until a version without a dot appears. If all of this is driving you dotty, there only remains one question: When did the Red Dot first appear on a Leica camera? The answer is in 1976 on the Leica R3, where it appeared as a red dot bearing the ‘Leitz’ legend.

And at around the same time, it appeared on the front of some Leica M4-2s

The red dot has been around for almost half of the life of “The Leica”. While the older enthusiasts will say that this is a comparatively recent development, bearing in mind that Leica cameras were only just over halfway towards their centenary in 1976. That said, this British Leica Catalogue from 1933 has something suspiciously familiar on its front cover.

Leica Heritage: The milestones

So, we have identified many aspects of a Leica Heritage, such as

- Form factor and compact size

- 24x 36mm photographic frame — film and digital

- Rangefinders – separate and combined with viewfinder

- Fixed and then interchangeable lenses with LTM and then M mounts

Leica staff

But the most important aspects of Leica Heritage are the people who own and work at the company. As in the past, the people there today seem to have a passion, which is rare among the teams at commercial companies.

In how many companies, which produce products of any kind, will an owner, in this case Dr Andreas Kaufmann, come to meetings of enthusiasts and talk to them directly about the company’s plans, projects, and products?

The same is true of all the senior staff, such as Stefan Daniel and Peter Karbe, and right down to the factory floor. Such as this group of staff in Porto last year, waiting to bring members of Leica Society International on a tour of their factory facility.

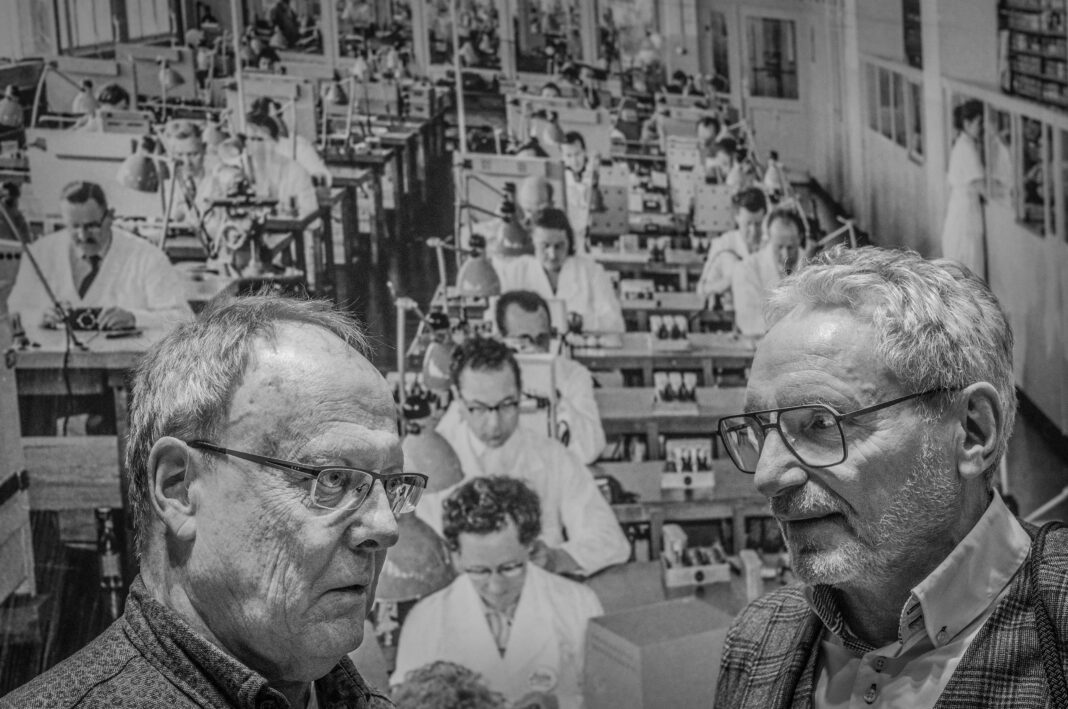

Nothing symbolises this heritage more than this photo I received recently from Frank Dabba Smith. The photo shows Peter Karbe, Head of Leica Lens Design, speaking with Ernst Michael Leitz, the grandson of Ernst Leitz II, in front of a picture of staff working on the M3 assembly line.

This truly encapsulates the Heritage of Leica, the past and the present coming together to produce photographic and optical instruments of extraordinary excellence.

Read more from William Fagan

Leave a reply and join in the discussion

The comments section below every article is a friendly, non-confrontational space where you can air your views without fear of stirring the sort of hornets’ nest that is so often a feature of websites. We welcome your views on the content of our articles, and your opinions on all aspects of photography are a lifeblood for Macfilos. Please let us know, in the section below, if you agree or disagree with our authors’ opinions — and please have no hesitation in adding your advice if you think we’ve overlooked anything important.

William, that’s a phenomenal article and a great credit to you for putting it together. It involved a lot of research and a great bit of editing to keep it a manageable length – not an easy task. Well done!

Great article. I am proud to have been a witness of this wonderful history since 1965, when I got my father’s Leica lllA.

Great article. My Leica history knowledge began about 1920. You have extended it back to 1849!

Thanks Dan. You can’t go too far back. I’m preparing a talk for April which goes back to 1839. History is like that. First Ernst Leitz joins the firm in the 1860s and then, almost 50 years later, Oskar Barnack joins and changes the face of photography. It is often the case that it is happenstance mixed with genius which makes the most progress.

William

Really great, William!

Bill Royce

Thanks Bill, Brian and Rene. Jim Lager, author of some of the best ever Leica books, liked the article which means a lot to me. I am starting to collect information about No 112, which Barnack assigned to himself, but I probably won’t write anything until much closer to the auction, perhaps in May.

William

A fascinating article on the history of an awesome family of exquisite cameras.

Thank you for a very interesting and well written article.

Great article William!Looking forward to meeting you in Vienna!

Thanks. We should see some of the items for the 100th Anniversary Auction while we are in Vienna.

William

Terrific read, thanks for a great article William.

Thanks Jono and Tom. Without these developments photographers would have no Leicas to use these days. The company has been a survivor, but some of that survival was due to vision of Barnack and others, which I have set out here as a form of heritage developed over a period of 100 years.

William

Excellent William – great article

best

Jono