It is said that when buying a property, all that matters is location, location, location. But the phrase sparks vivid memories for me. I was once in the right location, and undoubtedly at the right time. I was an eyewitness of the terrorist attack at the Munich Olympics in 1972 and my photographs were a world scoop.

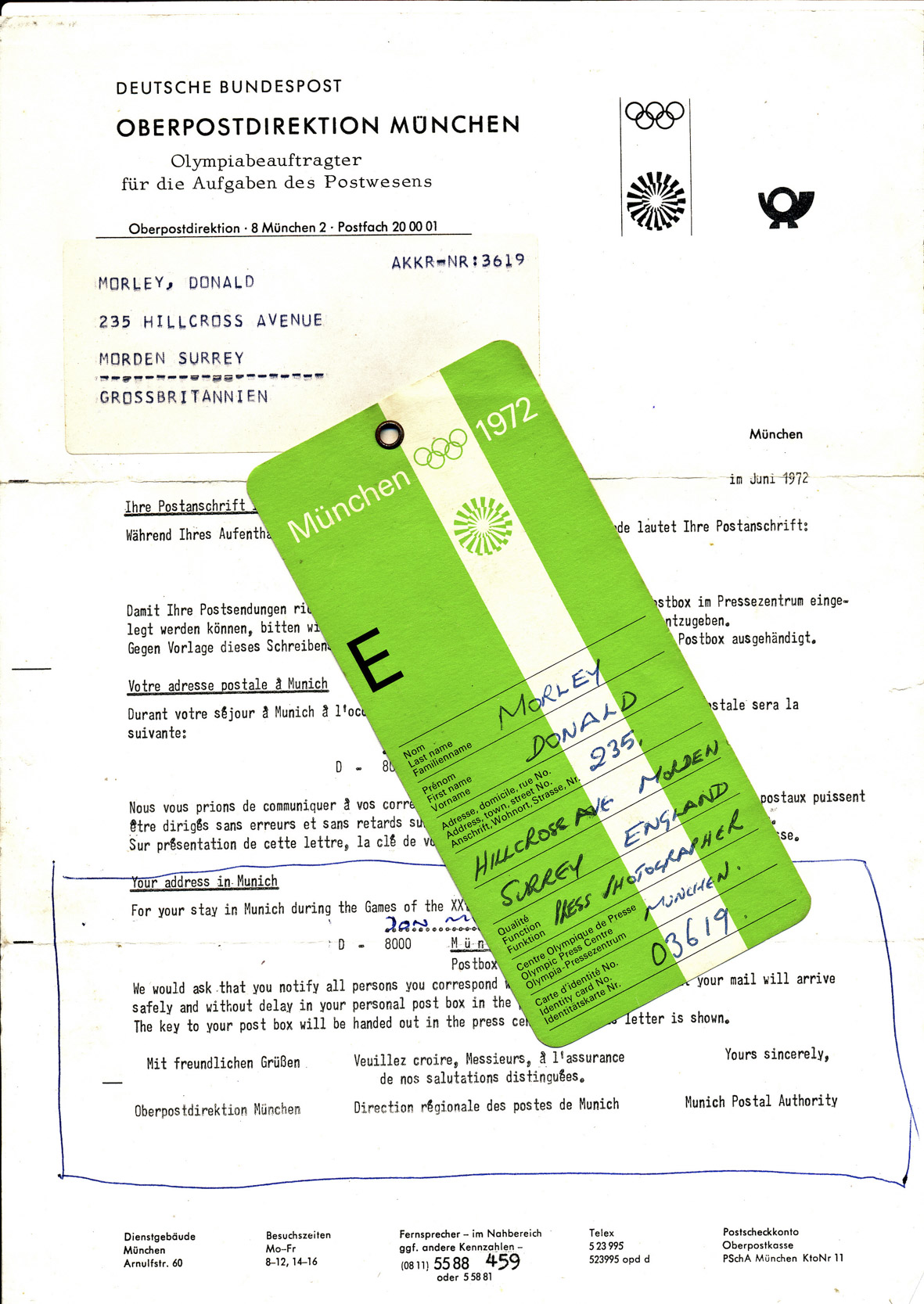

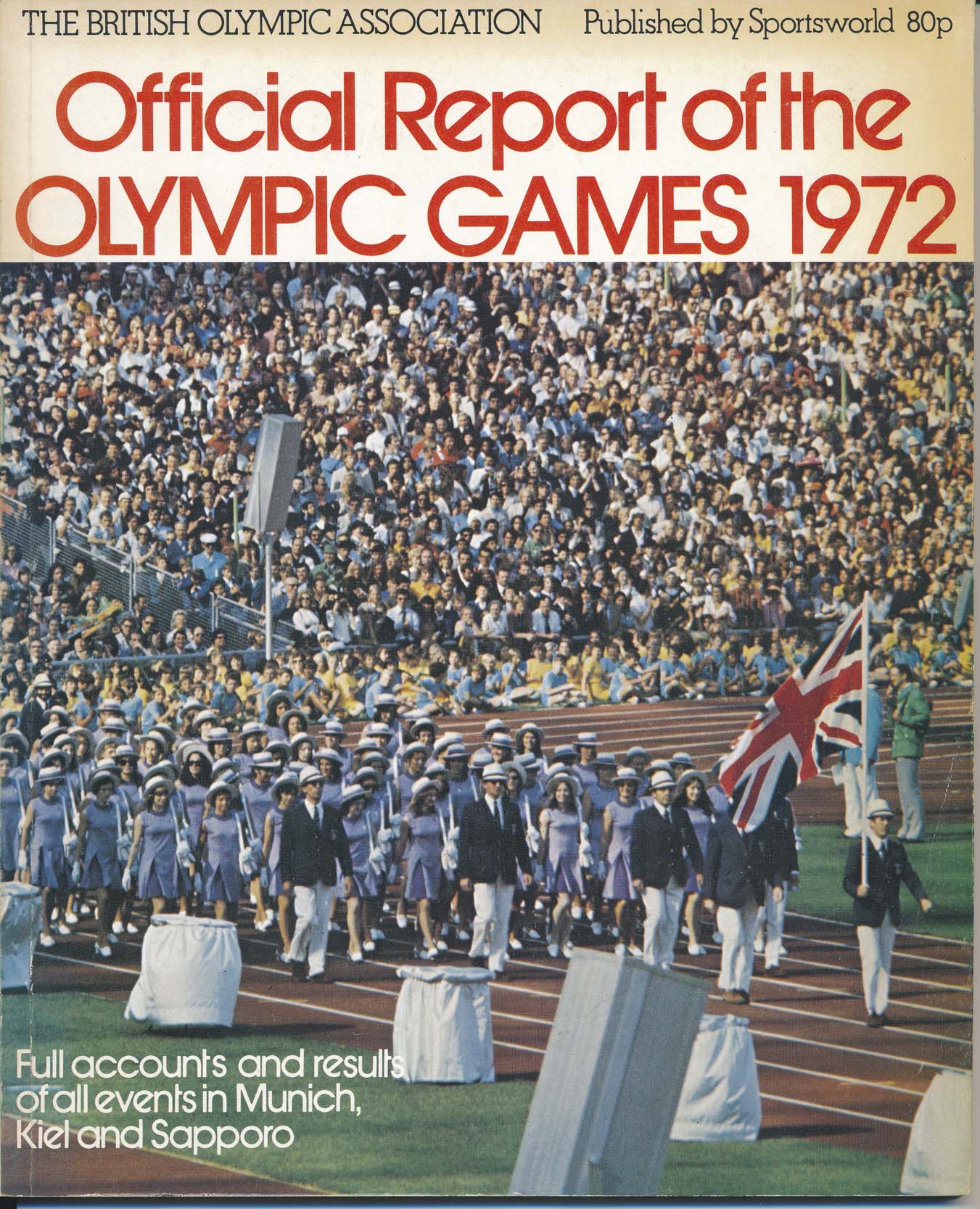

Where did it begin? I was representing the British group United Newspaper as an official photographer for the ill-fated Munich Olympics. I was working around the clock, covering events from early morning until well into the night.

And to fit in with publishing schedules world-wide, people like me had to get our films processed, then drive to the airport and see them safely on a flight to the UK. In short, it was a non-stop process.

Something afoot

The day all this happened, in September 1972, I had returned to my flat in the press quarters at 5 am, intending to crash for a couple of hours.

No sooner had my head hit the pillow than I was woken by a phone call from one of the British athletes, who thought they had heard gunfire. Something big was afoot in the Athletes’ Village, and my competitor friend thought I should get over there to see what was going on.

I grabbed one camera body, a 50mm f/2 and 300mm lenses, and ran at top speed (which was a lot faster than my current performance) for half a mile to the village gates.

Despite my producing all the right passes, the security guards would not let me in. I was on my own if I wanted to get any nearer.

Under the fence

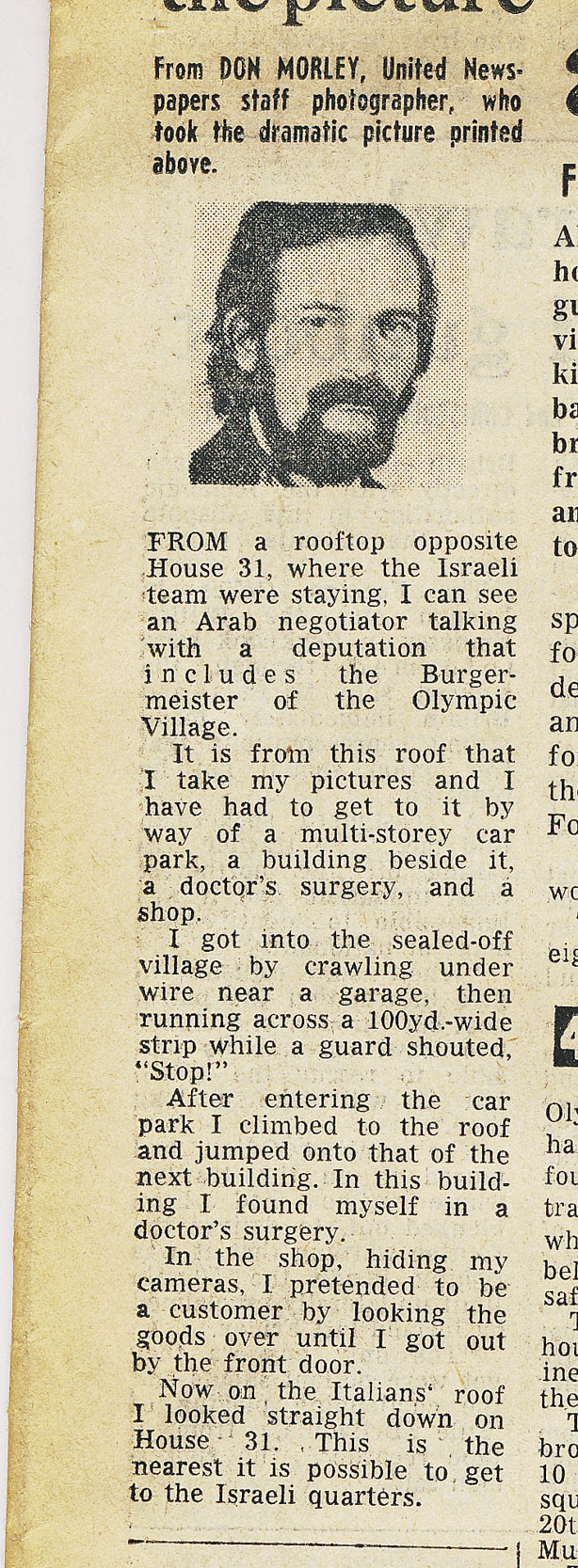

I skirted around the 12-foot-high security fence protecting the athletes’ village until, suddenly, I had a bright idea. I found a section of fence, near a garage, that I could crawl under.

Despite this progress, however, I was then faced with a similar-height secondary fence. There was nothing for it but to climb over, dropping my camera and lenses to the ground.

Prosaically, this all happened in full view of the security guards. They had been told not to let anyone through the gate, an edict they followed scrupulously, but no one had said anything about climbing over the fence.

Later, I began to suspect that the terrorists had gained entry by the same route.

Running across a hundred meters of no-man’s land, I entered the multi-storey car park and gained the sanctuary of the rear of the buildings. I decided to climb onto the roof of the car park and jumped across to the next building.

Moving down in the building, I soon found myself in the medical block, another unforeseen development, where I was confronted by a doctor covered in blood. “Are you injured,” he cried, as I rushed forward, disappeared through a back door into a shop. I loitered there a while, pretending to be a customer looking at the goods, until I was able to make my way to the front door.

Despite all the exertions, I had no idea what was happening. I had to deal with the immediate problems before venturing further.

Armed stand-off

Emerging from the front door of the shop, I first realised the enormity of the situation. I found myself right in the middle of an armed stand-off, with a terrorist holding a hostage over a balcony of House 31. The Munich Olympics would forever be associated with these events.

What followed was a wild chase and a series of lucky breaks and opportunities. This is a shortened version of what took place over the rest of the day. The armed police first tried to chuck me out, but they didn’t follow me (silly them…).

Fortunately, I managed to slip into the Italian team’s block opposite without arousing any further suspicion. Moving upstairs, I eventually found myself in a room at the same level as the terrorists’ balcony and started taking pictures.

Luckily, there was a phone in the room; I called my newspaper group’s office in London and gave them a running commentary as things unfolded.

Please, please leave

Later, I was spotted again by the armed police and thrown out of the room I had been occupying. Yet again, fortunately, they did not escort me, and I was able to walk down one floor, found another room and phone and continued where I left off.

By this time, it was mid-afternoon, and predictably there came a repeat performance. The police threw me out again, but I walked up one flight of stairs and ended up in the original room, complete with waiting telephone.

Eventually, there wasn’t enough light to take pictures in those days of film, but I kept up the running commentary until the buses came to take terrorists and hostages to the airfield.

Syndication

At this point, my job was over. My employers, United Newspapers, did a deal with Associated Press, which was then the world’s largest news agency.

They arranged that I would leave the village and hand over my film to AP, which would syndicate my pictures of the Munich Olympics, world-wide. This must have made my employers a considerable fortune, although nothing percolated down to the man at the coal face.

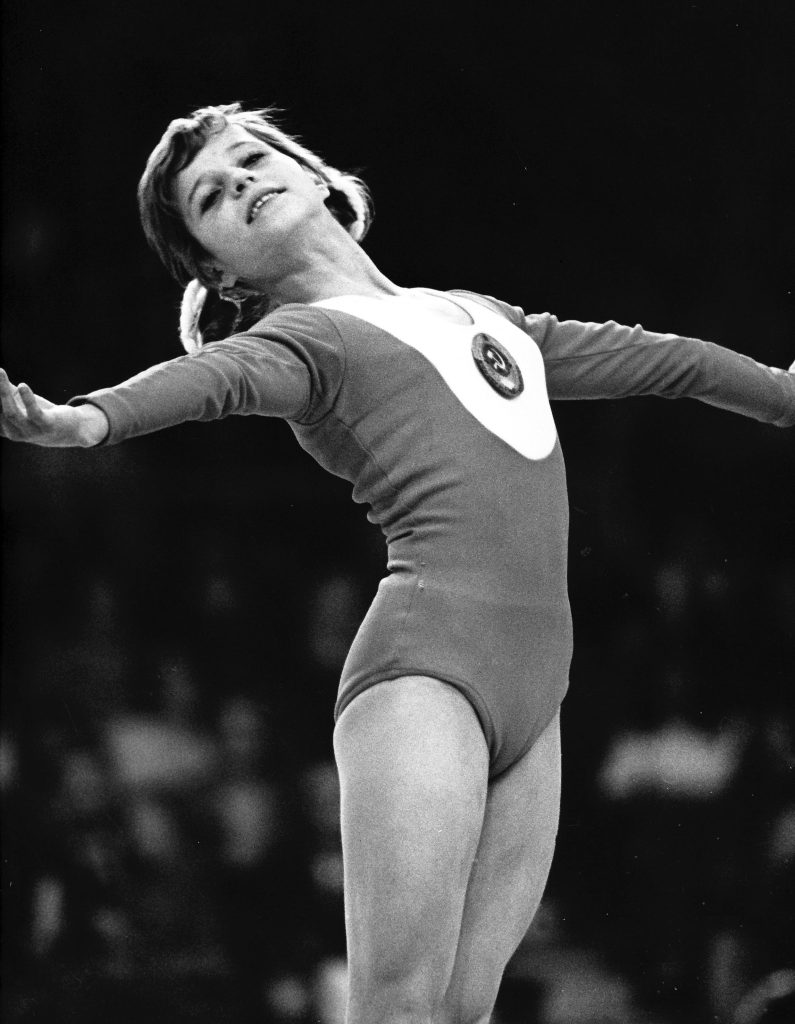

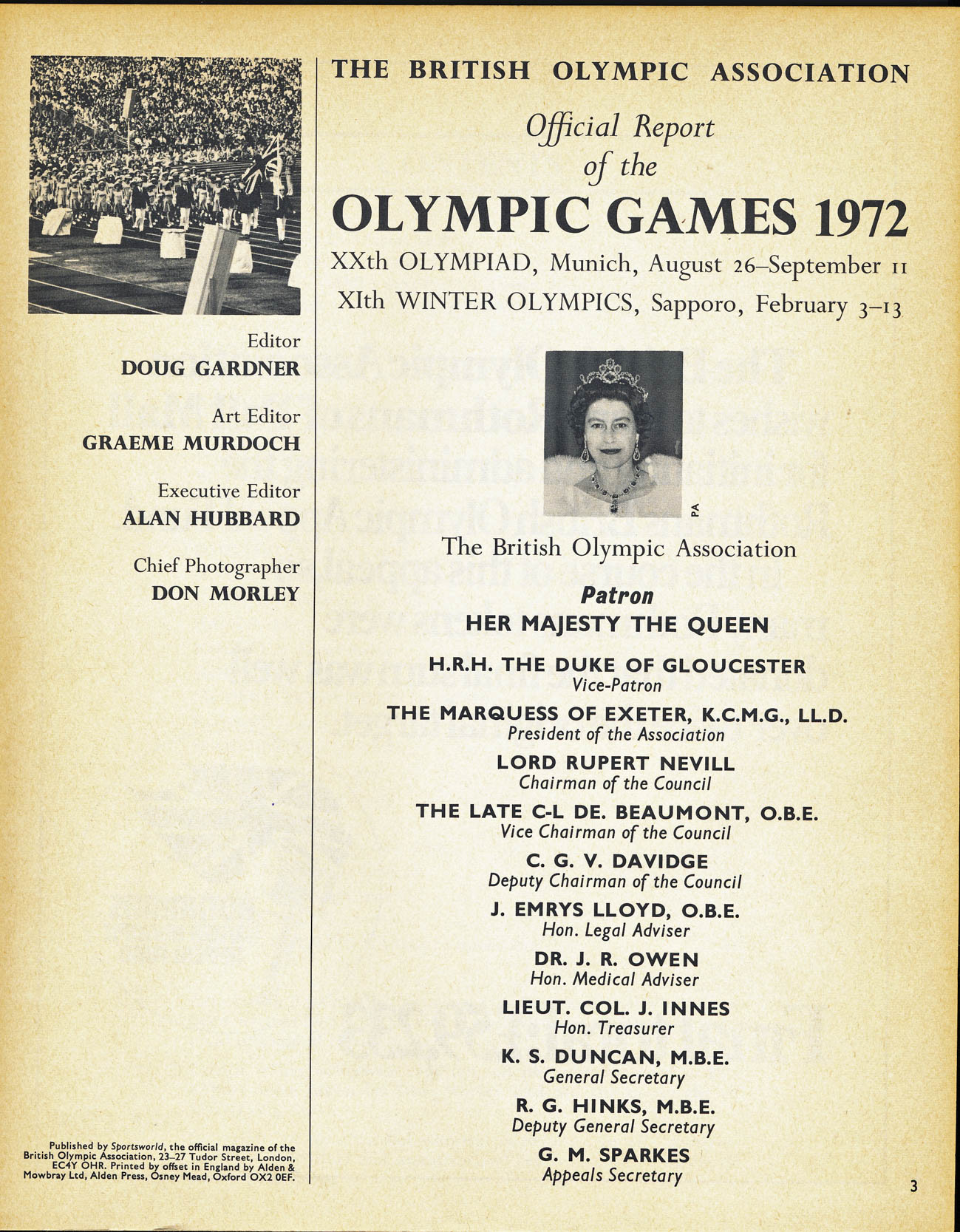

Subsequently, I went back to covering the aftermath and the re-started games. I was the official photographer for The British Olympic Association, in addition to my newspaper duties, and had plenty to do, even though it felt like something of an anticlimax.

Wonderful job, no bonus though

A week later, when I got back to London, United Newspapers threw a big party for me with Sir William Barnetson (later Lord Barnetson)1 and his fellow directors in the boardroom. There wasn’t even a bonus for me.

What I do have, however, is a nice certificate of thanks from the Munich Olympic Organisation, which now hangs on my office wall as a constant reminder of the event and its disastrous legacy. Oh, and a Munich Olympics tie…

Leica and a meeting with Leni Riefenstahl

It is interesting that Munich ’72 was the only occasion when Leica was appointed as the official Games camera. They had an on-site loan and repair service. Leica had contacted me before the games to offer as many cameras that I might need or want to try out.

However, I realised that once the Olympics started, I would be working under extreme pressure and would need to be completely “as one” with the gear. I did try the new SL and was not greatly impressed. Neither that nor any of Leica’s other SLRs were good as all-purpose professional cameras in my view. But the biggest problem then, and for many years later, was that the vital long lenses were inadequate.

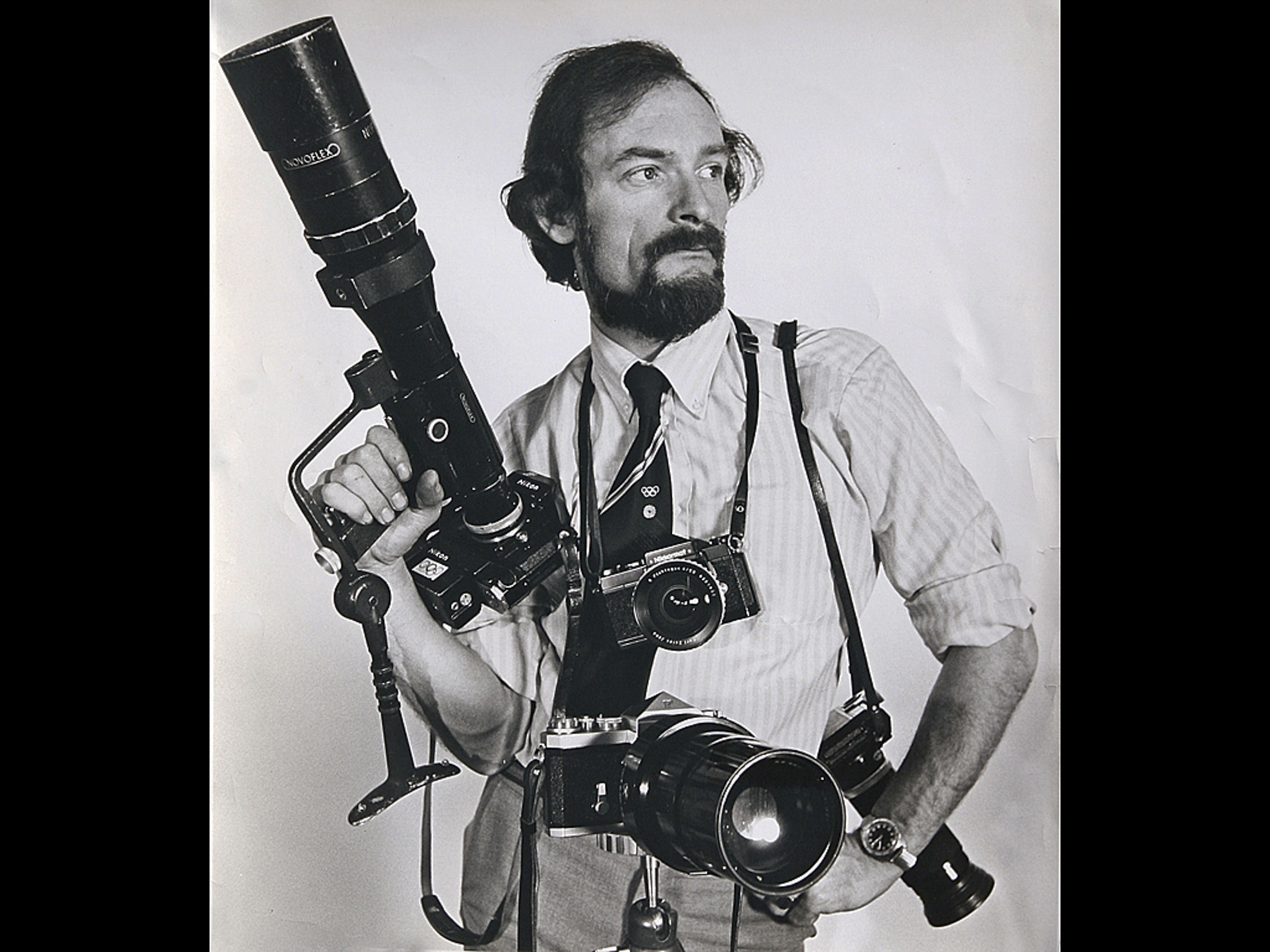

After various pre-Games experiments, I decided to stick with my Leica Ms and short lenses, ideal for boxing, indoor track cycling, gymnastics and so forth. But I also used Nikon Fs with motor drives for anything over 90mm. I still prefer my Novoflex 400mm f/5.6 Follow Focus lens over any of the contemporary Leica Telyts. I dare say that almost every other professional covering sport or hard news of that era would agree with me.

As a further aside, during the 1972 Munich Olympic Games I had the opportunity to work alongside Leni Riefenstahl, who had made that outstanding film of the 1936 Olympics. Andres Veiel’s award-winning documentary, Riefenstahl, is set to be released in UK and Irish cinemas this month and will be screened at the German Film Festival across Australia until May 28.

September 5th and an invitation

This brings us up to date, and to September 5th, the recent documentary-style film which introduced the terrible events of Munich in 1972 to a new generation. I was cogitating on this development and wondering if I should go to see the film, when I received an intriguing invitation from the Reigate Photographic Society.

My wife Jo and I were invited to what was described as a “private showing” of September 5th at the local cinema in Reigate. Couldn’t resist that.

It transpired that the society had invited members of almost every other photography club in South East England.

We were collected by car, fed and watered at the cinema before being ushered in to what proved to be a packed house. Before the film, the organisers showed a filmed interview with me, followed by a slide-show featuring almost a lifetime of my pictures.

Then, after the showing of September 5th, I was invited to the stage to answer questions. It was a wonderful occasion and, taken by complete surprise, I was delighted but, at the same time, emotional.

My shots were unique

When I watched September 5th, I immediately noticed that all the period clips were taken from a mound which was located a considerable distance outside the village. I realised that mine are the only pictures I have seen from the left-hand side, from within the village itself.

With modern technology and security, including CCTV, it is unlikely that a journalist or photographer could penetrate a security cordon such as this, and even more unlikely that they would evade scrutiny by moving from room to room.

Editor’s Note:

The author, Don Morley, and I have been friends for over 60 years. I first met Don when we worked together at Associated Iliffe Press in London. He was a staff photographer working on magazines such as Autocar, Flight, Amateur Photographer and Motor Cycle. I was a rookie journalist writing feature articles and road testing new models for Motor Cycle magazine, then the leading weekly of its type.

Don had started his career as an engineering apprentice at Rolls-Royce in his home city of Derby, and later retrained to become a staff photographer.

He was already a Leica enthusiast and would carry around two IIIfs, one loaded with colour and one with black and white. He built up a reputation as a sports photographer, specialising in motorsport. On one memorable occasion, at the Oulton Park race circuit, a Bentley swerved off the road, demolished the mound on which he was standing and buried one of Don’s precious Leicas.

Don had to make a special request to import a replacement IIIf, but was bitterly disappointed to find that, when it arrived, it had morphed into the newest version, the IIIg. Outraged, Don managed to swap the new IIIg for a second-hand IIIf and continued as before.

Don went on to a successful career in Fleet Street, covering general news, wars, show business and sport. Later, when United Newspapers closed the magazine “Sportsworld”, Don did a deal to buy out the entire colour picture library. He then co-founded the All-Sports Photographic Agency with Tony Duffy and others in 1975. This is now part of Getty Images.

Above: Photographing motorcycle sport has always been a firm favourite with Don. The above images are now the copyright of Allan Hitchcock of Hitchcocks Motorcycles Ltd (info@hitchcocksmotorcycles.com) of Solihull, B93 0EY. They may not be reproduced without permission.

An interview with Don Morley

- William Denholm Barnetson, Baron Barnetson, newspaper proprietor and television executive. d1981. ↩︎

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

Lovely to see your story here, Don. I have heard it from you before and also about your equal bravery in Northern Ireland where your long lens almost got mistaken for a sniper’s rifle. I must look out for that Reifenstahl film. A friend of mine in Limerick has a collection of cine cameras of the same types that Reifenstahl used to film the 1936 Berlin Olympics and he manages to use them today. One would like to think that what happened in Munich in 1972 could not happen again because of increased security, but, as you know, it is often the case that we take one step forward and then two steps backwards.

When you were taking photos of motor sport did you ever come across Louis Klemantski? I have a book of his motor sport photos which also shows him using an LTM Leica, literally on the edge of a race-track, and it looks like that if he stuck out his arm he could touch the F1 drivers passing by.

Different days, indeed, Don.

William

Hello Dunk. I had one of those later Telyts and have today ir was so needlessly heavy I thought Leca needed to suppy any user with A Sherpa to carry it, it was just plain daft making such for Pros who already had too much to carry, no wonder they did not sell many. Best wishes, Don

Thanks Don,

The story is spellbinding and we know how powerful and shocking were the images at that time. And they still shock! It’s also worth noting the personal risk you took. Others might have shrugged their shoulders and returned to your room, but you kept going despite being turned back. Kudos.

J

A fascinating story Don and a very enjoyable read. I visited the stadium in the mid 1970s and the events were still fresh in people’s minds. Your photos told the story.

Wow. Inspirational stuff. Kudos for taking advantage of the conditions to produce unique work.

Wow, what a story and what courage going way beyond reasonable expectation.Thanks for sharing the detail of the event. Perhaps your friend Mike can coax you into sharing some motorcycle sport tales!

This is your life, Mr Morley – thank you so much for sharing.

Wonderful article Don. You thoroughly deserved very much more than the Munich Olympics tie for your considerable efforts and risks taken. I’m also a Novoflex enthusiast and especially enjoy using the 3 element 400mm ‘T’ Noflexar – which easily adapts for use with Leica R APO extenders. Mention should also be made of the many motorcycle books you’ve written covering so many different marques and including ‘trials irons’, your modifications, and riding same. One of the Leitz Telyt lenses made available for the 1972 Olympics was the Telyt S 800/6.3 which weighs almost 7 kilos plus its case. Leica ‘lost the plot’ with the modular 5-section behemoth (takes c.5 minutes to unpack and assemble) and sold relatively few of them.