On October 8, 1871, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow reputedly kicked over a lantern in a crowded barn that started an architectural revolution. Chicago, at the time was built largely of timber with only a few buildings in brick or stone.

Most of the wooden buildings burned to the ground, leaving the city a smouldering scene of devastation and ruin. Three hundred people died, 100,000 were left homeless and 127,500 buildings were destroyed. That was the Great Fire of Chicago. So, what happened next?

Where it all started

The real answer to the question lies in what followed the Great Fire. Chicagoans are known for their ambition, creativity, stubbornness, and a sense of being overlooked. Carl Sandberg called Chicago “The city of broad shoulders. Hog butcher to the world.” You might call it “a chip-on-the-shoulder” but we call it “Second City-itis.”

The city set out to rebuild with new safety codes to prevent the same disaster happening again. Buildings would have to be made of stone and brick, not wood. Those safety codes became the foundations of an architectural revolution.

Rebuild it and they will come

Pressure to rebuild was enormous as the city had grown rapidly from a fur trading post in 1830 to a major manufacturing and distribution centre by the late 1800s.

Nevertheless, the city fathers had the good sense to arrange the “new” Chicago in a grid pattern. Sequential numbering subsequently followed in 1904. “Ground zero” was at the intersection of State (running north/south) and Madison (running east/west). Once you knew that, the city became easier to navigate.

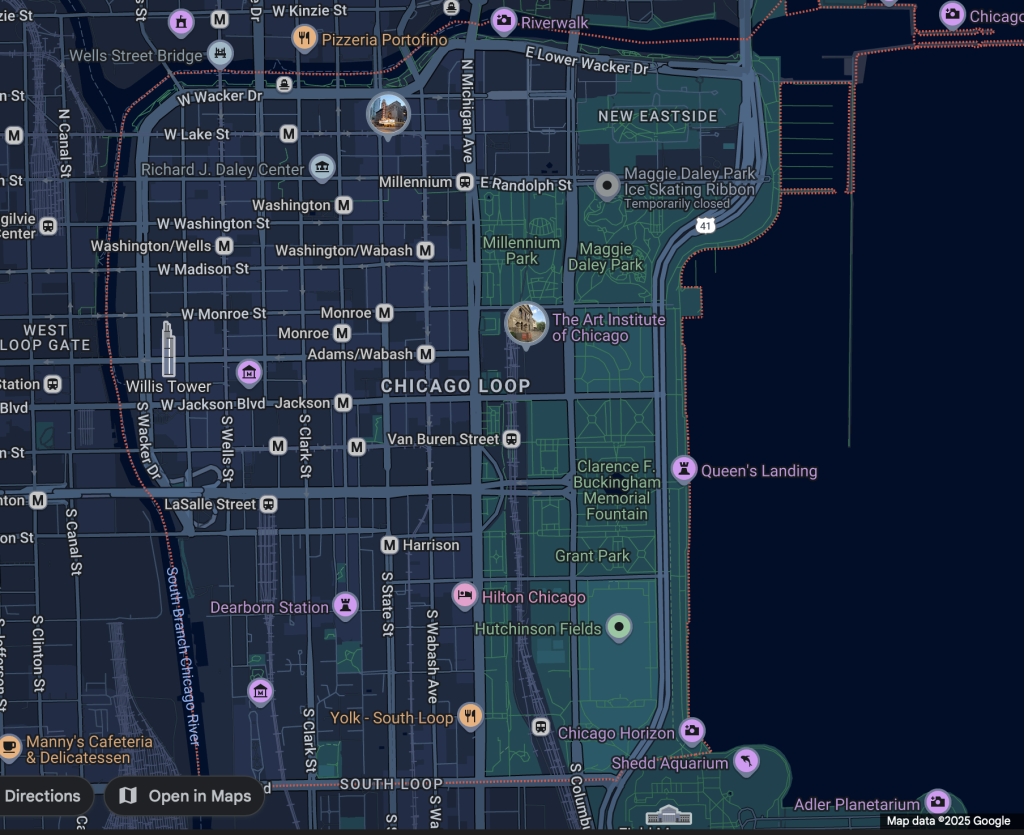

The Loop is the main business district area of Chicago

Wacker Drive forms two sides of a square and acts as a boundary for “The Loop” which is Chicago’s original business area. Wacker Drive was completed in 1926 after featuring in Daniel Burnham’s 1909 plan for the city. The “L” or elevated train system runs around the Loop and creates another demarcation of the business city centre.

Establishing a new school

Chicago was also wealthy and becoming more so: the founders of some of the leading companies decided to use the fire to rebuild the Loop in a way that matched their ambitions. That doesn’t cover the innovative engineering, design sophistication, or financial clout it took to rebuild a different kind of city: it took an architectural revolution.

This ambitious drive to rebuild led to the Chicago School of Architecture and the birth of what was essentially a new city in the late 1800s to the early 1900s.

The Chicago Style encompassed: steel-frame construction, the idea that form should follow function, and the embrace of new technologies. All of that led to the “International Style,” which in turn led to the Second Chicago School of Architecture that developed from the late 1940s to the late 1970s to form the next wave of the architectural revolution.

Take a walk around Chicago

So, let’s take a walk around some of these historic buildings, and some that may get that designation in the future. Architectural tours walk this central Loop area of Chicago every day, and you can take a river version, if you prefer, that takes you out onto the lake and down both the north and south branches of the river.

The AON Center

My first stop is the AON Center to the east of the Loop. It was originally called the Standard Oil Building or “Stan.” Later it was renamed the Amoco Building, and later still the AON Center. It was part of a new burst of competitiveness, civic drive, and desire for prestige in the late 60s through the 70s.

It was designed by Edward Durrell Stone in partnership with Perkins and Will, who were at the forefront of the second architectural revolution. The 83-storey building was engineered to reduce sway and structural column bending and to maximize available floor space. It was briefly the tallest building in the world before the Sears Tower was completed.

Errors in design

When I worked in the building, I was surprised when working late one evening to see that the three boxing punchbags in my company’s lobby were swaying in perfect unison. I also felt seasick as I walked through the building and wondered why I could hear creaking that sounded like it was coming from an old sailing ship. Yes, the building sways by several feet despite those anti-sway engineering features.

The building was not without other “issues.” It was originally clad in thin Carrara Marble slabs. Not long after construction, and during winter, one slab fell and damaged the roof of the adjacent building, inspections showed these slabs could bend and fail due to ice forming behind their surface. Eventually, the building was re-clad in white granite at a cost of $80 million…

Pritzker Pavilion

You can look down onto the Pritzker Pavilion from the AON Center across the street. Frank Gehry designed it to be the centrepiece of the newly developed Millennium Park, which was built above the Illinois Central rail yards using air rights bought by the city. The design of the pavilion follows Frank Gehry’s style seen in the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

The pavilion is the home of the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra and Grant Park Music Festival. It’s an absolutely beautiful park to spend a summer’s evening in, listening to music or having an alfresco picnic on the lawn while watching classic movies.

A foundation for a new city

The Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 had further encouraged ambition, boldness, and confidence in the city to kick-start an architectural revolution. The names of the architects who followed in its wake are renowned around the world; from Louis Sullivan to Mies van der Rohe, Frank Gehry and beyond.

A walk across the Loop from Millennium Park will take you to the Monadnock that was completed in 1893 in the South Loop of Chicago. It was the world’s first skyscraper, using pioneering frame construction made from brick, wrought and cast iron, and a founding example of Chicago’s architectural revolution.

But that’s really only half the story. The north half of the building was designed by Burnham and Root and construction started in 1891. The later, south half, was constructed in 1893 and designed by Holabird and Roche.

It was the second tallest load-bearing brick and masonry building ever constructed. When built it was the largest office building in the world. On the ground level you will find a variety of shops: a barber’s shop, a milliner’s and restaurants. It’s a building of real character.

A flair for the future

Head a little west and further into the Loop and you discover an unusual building that forms a distinctive half-pyramid shape with curving facades. The architects were CF Murphy and Associates, Stanislaw Gladych, and Perkins and Will. The building was completed in 1969 and became the First National Plaza for The First Chicago Bank. It feels very 70s. Time to get out the flares, big-collared shirts and stacked shoes.

The framework for a new type of building

Walk a bit further across the Loop to the heart of the financial area and the impressive LaSalle Street. The Rookery building is one of the most significant buildings in Chicago. It’s a great example of what was at the time the new and architectural revolution of frame or skeletal approach to building taller structures. A walk around the inside of the building shows how it was supported by that skeletal structure.

It was designed by Burnham and Root in 1885 and completed in 1888. At 11 storeys high it was one of the most impressive buildings in the world at that time. In 1905 Frank Lloyd Wright redesigned the 2-storey lobby that you can see in my images. Truly a beautiful foyer that is often used to stage wedding photographs.

Go big, or go home

Keep walking west, and you cannot miss the Sears Tower (sorry, Willis Tower) looming over the Loop. Chicagoans still call this building the Sears Tower after its first owners. It stands out on the Chicago skyline regardless of name, as an architectural revolution, by being 110 storeys, and 1451 feet (ca. 442 m) tall. Bruce Graham designed the building as nine square “tubes” bundled together in different heights. It opened in 1973 as the world’s tallest building.

The day before the event, the Chicago Tribune’s editorial board wrote: “Move aside, New York! After tomorrow, when schoolchildren dream of big buildings, they’ll no longer think of you and the Empire State Building or the World Trade Centre.” I have attended numerous meetings on the higher floors, looking out over Lake Michigan. You can see all the way to the state of Michigan across the lake. It’s hard not to let your attention wander from the meeting.

The arrival of Post-Modernism

Head north, and momentarily you see a strange skeletal structure in the process of renovation. The James R. Thompson Centre was until recently a State of Illinois building designed by Helmut Jahn and built in 1985 in what is described as a Post-Modernist style. The execution of the design proved costly with leaks, the need for a more expensive air-conditioning system to offset all the glass panelling, and other structural challenges.

The State planned on tearing it down, but Alphabet/Google came to the rescue and agreed to purchase this historic building and restore it as their Chicago Googleplex. It has featured in TV shows and movies and was the exterior for Gotham Square Garden in the 2022 Batman movie. It’s a very difficult building to photograph as the reflections at times almost look as if windowpanes have been broken. Dusk is probably the best time to capture it.

Let’s stop for lunch!

The Berghoff is not the oldest restaurant in Chicago, (that title belongs to Daley’s Restaurant in 1892) but it’s well worth a stop for hungry and thirsty walkers. The Berghoff opened in 1898 and apart from Prohibition has been serving beer and German food ever since. Wiener Schnitzel and a chilled pint of German lager should keep us going for a while!

Part II of this architectural walking tour will be along shortly!

More from:

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

A fascinating read, Jon. the pictures aren’t half bad, either.

Great pictures and a fascinating historical journey. Thanks.

Great commentary Jon! Pictures great too…. of course!

I’m looking forward to Part II 🙂 Wondering if you’ll get north of the river and see the old Water Tower (and the new one).

Ah, the Berghof. I think it was around 1970 — I had my first frog legs there. Perhaps just a bit of Continental cooking?

Thanks Kathy, I go north but to the Hancock building as my last stop. No more frogs legs at the Berghoff these days. Just solid German food.