A brief recap before continuing our walk around some of Chicago’s notable architectural and historic gems. The story really starts after the Great Fire of Chicago happened in 1871. That fire started an architectural revolution that changed the face of Chicago forever. If you would like to know more about what happened after the fire and some buildings I already commented on, turn to Part I The Great Fire of Chicago: An architectural turning point of this article.

A space-age future

If you head west to the edge of the Loop and close to the south branch of the river, you will see a building that was originally known as the “Hyatt Center.” It was designed (I.M.) Pei Cobb and Freed Partners and completed in 2005.

It’s an unusual and strikingly shaped building that in plan form looks like a lozenge. It also includes extensive exterior and interior landscape gardening. If you’ve been to Singapore’s Changi airport you will get the idea. It’s a dramatic building to look at from street level, particularly through the TL 11-23mm lens.

Where the river divides

As you continue north, you come to the “Y” point where the north and south branches of the river diverge. In its early life this building was known as North Riverside Plaza but has recently been rechristened “River Point”. It provides a dramatic focal point when looking west along the river, particularly towards sunset when other buildings are reflected off its the curving façade.

For those who get nerdy on architectural details, Pickard Chilton designed the building and it was developed by Hines. Mr. Chilton had designed the building before the Great Recession struck in 2008 when financial challenges froze its development. Chicago’s architectural revolution continues with River Point including a city park that is built over railway tracks heading into Union Station, and also by being built above the CTA Blue Line. It’s a complex picture when see from above.

A new focal point

The most dramatic of the three high-rise buildings owned by the Kennedy family is the Salesforce Tower. It’s 835 feet tall and was designed by Pelli Clarke. The building was completed in 2023 and sits just to the north of where the Chicago River diverges between branches.

The beauty of these buildings is that they make the most wonderful use of the light as it shifts from rising over the river in the east to setting over the point where the north and south branches of the river divide. Winter or summer light makes for an arresting image.

Building on a different scale

The Marshall Field and Co department store chain originally owned the land on the north bank of the Chicago River on which the Merchandise Mart stands. Marshall Field developed the Mart to become a wholesale centre that consolidated 13 different warehouses into one location.

At its height, it had its own rail line that linked it to the Chicago rail network which fanned out across the country. The building also incorporates part of a CTA “L” line station.

And you really can’t miss the Merchandise Mart. Like the Sears Willis Tower, it dominates, in this case the river frontage. It had been designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst and White to act as a “city within a city”. You may notice throughout this pair of articles that the architectural revolution of Chicago’s buildings is prone to aiming for and hitting every “x-est” superlatives it can.

When the Art Deco style Mart opened in 1931 it was the world’s largest building with four million square feet of floor space. It is so large that it has its own zip code. As an aside, it used 29 million bricks, 380 miles of wiring, and four million cubic yards of concrete, approximately 10 miles of corridors, and 30 elevators.

So maybe it deserves a little “x-est” bragging right. I once worked in the building, and it’s difficult to grasp the size of it until you walk from one end to the other end looking for somewhere to grab a sandwich. In summer, “Art on the Mart” uses the 2.5-acre façade as a canvas to project digital artwork. It makes for a pleasant way to spend a summer’s evening on the river.

Another city within a city

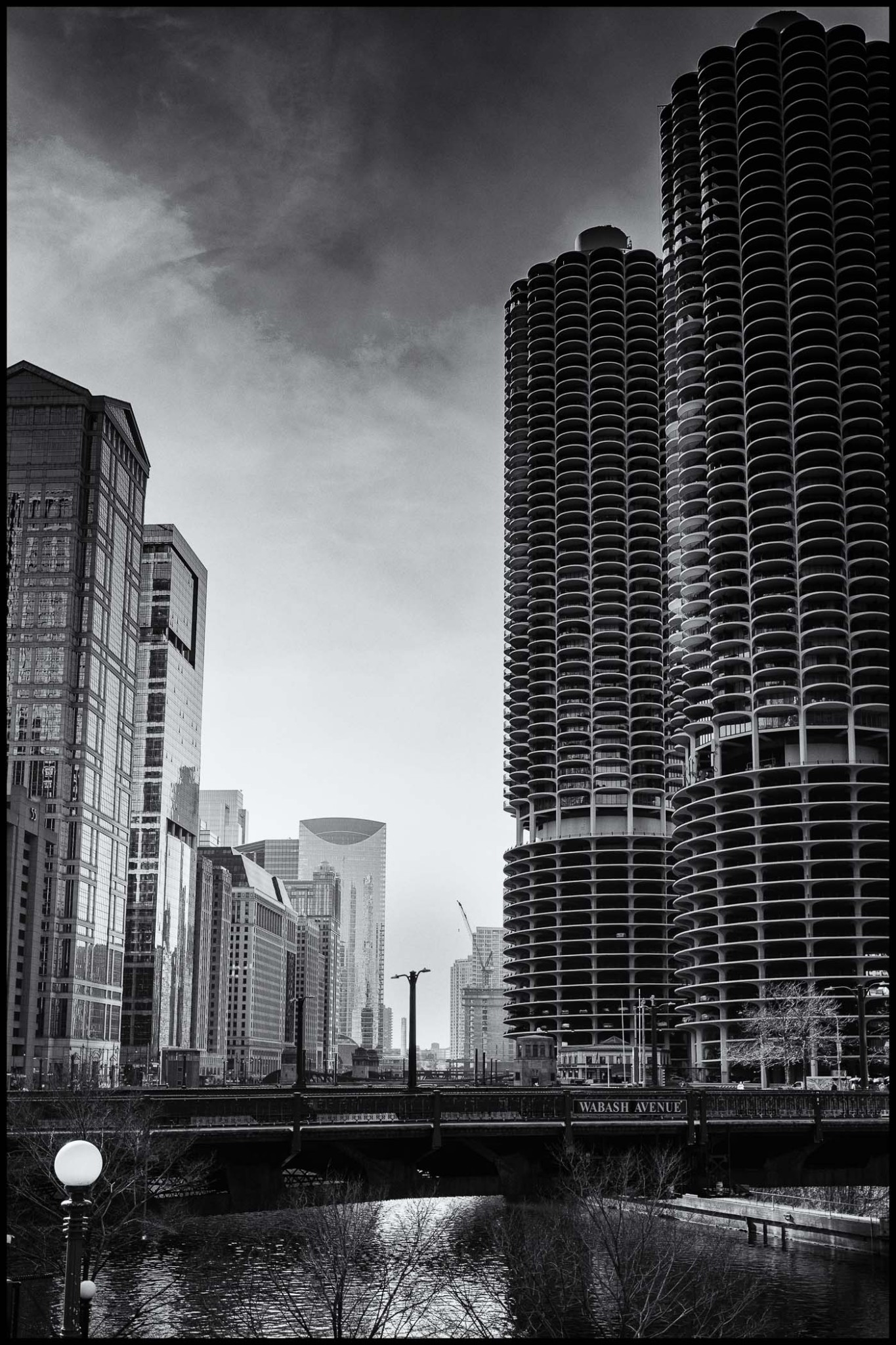

Walking back east along Wacker Drive and you can see the architectural revolution of the Marina City complex across the river. It was designed by Bertrand Goldberg in 1959 around two towers that resembled “corn-on-the cob,” a hotel that wraps around the “cobs,” an auditorium theatre building (now House of Blues), an ice rink, and below that, a small marina for private boats. And let’s not forget, valet car parking for about 900 vehicles.

The slightly oddball feeling of the building is created by the lack of internal right angles. Imagine looking down on a stacked circle of “Laughing Cow” cheese wedges, and you will get the idea of what it might be like to live in one of the wedges. I once tried to rent an apartment there as I thought it might be an interesting experience, and I could walk to work. Sadly, it was a hot property to live in even in the late 90s.

Want to know how Marina City fits into popular culture? It’s on the back cover of Sly and the Family Stone’s “There’s a Riot Goin’ on.” It also features in the movie “The Hunter” starring Steve McQueen, where, in a chase sequence, a car drives off the building into the Chicago River. More recently, it has appeared in an episode of “The Bear.”

Less is more

Keep walking east along the river, and you arrive at the former IBM Plaza, now AMA Plaza. It was one of a series of 14 buildings in Chicago, including the IIT campus, designed by Mies van der Rohe. They all follow his “less is more” minimalist approach to design. They exhibit subtly different details, like appearing to float above ground due to being built on pillars. The IBM building is an obvious relative of the Seagram’s building in NYC. It now incorporates the American Medical Association and the Langham Hotel.

Room with a view

The Trump organization wanted to build the tallest building in the world. But after the September 11 attacks, it was scaled back and became the second-tallest building in the USA. It sits on the site of the former Chicago Sun Times offices and printing plant. It has a spectacular roof deck with views out along the Chicago River towards Lake Michigan. Well worth the price of a drink on a summer’s evening.

The 1,400-foot tall, 100-storey building was designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and completed in 2009. The architectural revolution of the building was how it incorporated “setbacks” to give both a stepped appearance with rounded curves, and also how it was designed to combat wind vortexes at street level.

The arrival of air-conditioning

We’ve now arrived at Michigan Avenue, which is the main north-south shopping street that crosses the river at this point. The Wrigley building was designed by Graham, Anderson, Probst and White to be the new headquarters for the Wrigley (chewing gum) company.

The design was apparently influenced by Seville’s cathedral and was built as two different height towers. It has terracotta cladding of both towers, with skybridges linking them. It was also an architectural revolution by being the first air-conditioned office building in Chicago.

Stop the presses

For a while the Tribune was one of my clients, and you felt that you were stepping into history when you walked into the large editorial boardroom. In 1922, the Chicago Tribune chose to mark the paper’s 75th anniversary by hosting a design competition for their new headquarters.

John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood won the competition and delivered what can best be described as “a well-established neo-Gothic theme”. The design beat out more contemporary offerings from Eliel Saarinen (father of Eero), Walter Gropius, and others. If either of their designs had been preferred, it would have dramatically transformed Chicago’s skyline.

Putting the skeleton on the outside

And finally heading north up Michigan Avenue you arrive at the unmistakable John Hancock Center. It was originally commissioned by the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company, which was both the developer and the first tenant. The design was described as “Structural Expressionism” featuring the structural x-braced beams on the exterior of the building that provide support and stability.

The architect was Bruce Graham, who worked with the pioneering structural engineer Fazlur Khan from Skidmore, Merrill and Owings. From 1969 to 1973 it was the tallest building in Chicago. Pre-Covid there was a Skydeck that gave 360-degree views of four states, with a bar and restaurant as a major tourist attraction. The company that manages the building I happen to live in has offices here. It’s difficult to pay attention when the view is straight out to the lake, with sailboats catching the breeze in summer.

The end of one road and the start of a new one

Conclusions. This is not an exhaustive view of all the historic architectural treasures in Chicago. I have included 17, and you could do a superficial look at all these in one day if you wanted to. If you’re interested, there are architectural boat tours and walking tours with commentary from docents, who know their stuff.

I happen to have a relative who is an architect and who has worked for one of the names on my list of companies who designed some of the great buildings. It’s hard not to feel a sense of civic pride when you discuss these buildings. I could have added another dozen, but I have spared you until I have the strength to write a Part Three!

Postscript “The Bean”

It’s not a building but…. And it’s really called “Cloudgate”, designed by Anish Kapoor, and built between 2004 and 2006. It’s dramatic regardless of the season and a huge tourist attraction that draws visitors to photograph themselves and their reflections.

Shoot!

These images were all shot on a mix of D-Lux 109, CL (with TL 11-23mm, TL 18-56mm), Q2, and Q3 on various walkabouts in the downtown area.

I don’t have a camera that would support a tilt/shift lens for a “step back view”, nor do I currently have a tripod. The nearest thing that will work for me is the CL + TL 11-23mm lens. In good light this combination works beautifully, but you can never escape from the optical characteristics of a lens this wide and when you are not perfectly and perpendicularly aligned.

Exaggeration is something you can fight, but in reality, you might as well embrace it. It’s a shame Leica never continued to develop the CL: a highlight weighted metering option, as the Q3 has, would have helped. And a folding rear screen would also have been useful for some of these shots.

More:

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Excellent& informative article, Jon.

Wonderful follow up article. Interesting how modern skyscraper architecture has developed all around the world

For me, as a former Chicago resident, this was interesting throughout. I’d known these buildings by sight, but had no idea of all the history behind them. or of the river development.

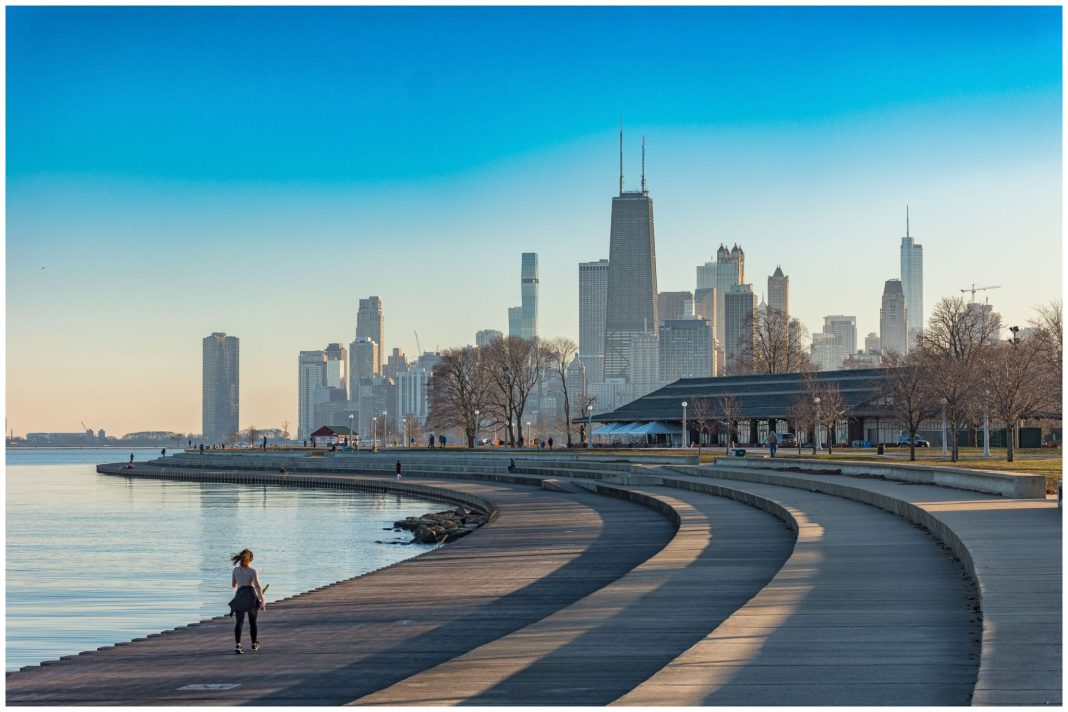

Just curious — I loved the lead-in photo, with the runner by Lake Michigan. Where was it taken?

Thanks Kathy,

Just north of Fullerton Ave. As it happens, late afternoon in early December! Chicago fooling us into a false sense of security! “Snow? What snow?”

Thank you, Jon, for taking us around Chicago. Great architecture, described with a lot of knowledge and captured in stunning images. Makes me want to travel there! And also thank you for all the work you are doing for Macfilos – many of our readers might not know that Jon is not only a distinguished author, but also an indispensable member of the editorial team. All the more amazing that he still finds time to write for all of us. So, thanks again, Jon! Jörg-Peter

Many thanks J-P! It was fun to do.