The terms “compact” and “medium format” are not natural bedfellows. Yet, Fujifilm has managed to turn oxymoron into opportunity. The GFX100RF is a remarkable medium-format camera that is surprisingly compact, making it an attractive and capable everyday carry device. This achievement marks a significant milestone in the world of enthusiast, high-resolution fixed-lens compacts — a genre pioneered by Ricoh, Leica, and Fujifilm.

This innovative camera represents a significant departure from the conventional approach. It is undoubtedly an important camera, and a milestone in the development of fixed-lens shooters. So important is it, that we were prompted to acquire one of the first Fujifilm RF cameras back in April 2025. Over the past four months, I have used the GFX100RF extensively and have come to appreciate its numerous advantages while acknowledging the few shortcomings.

It is intriguing to consider how such a substantial amount of functionality can be accommodated within a remarkably compact body-lens combination, resulting in a weight that is comparable to Leica’s full-frame Q3. The answer lies in two compromises that some believe are deal-breakers. First is the lack of image stabilisation for still photography, something which is unusual these days. Second is the “slow” f/4 aperture, which has an effect on low-light performance and the ability to create artistic subject separation. More on these aspects later.

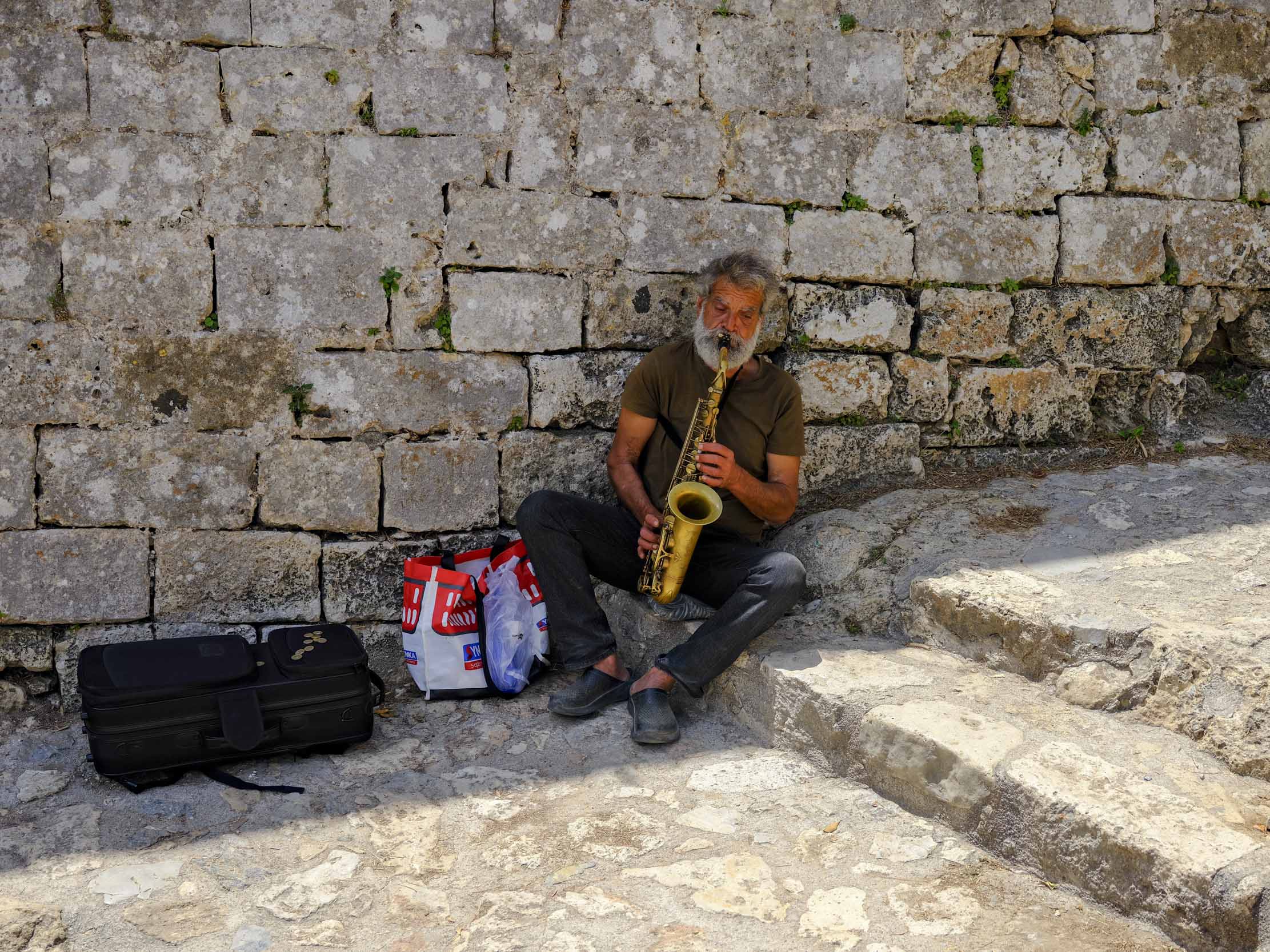

While these compromises cannot be overlooked, the camera redeems itself by its exceptional performance in normal use. It excels in landscape, architectural and “street” photography (lacking a better term), and its portrait capabilities are limited only by the wide-angle lens — common to all current fixed-lens cameras except for Leica’s 43mm Q3 43.

The RF, like the Leica M, it is a camera designed for deliberate and thoughtful photography, and it is masterful in this role.

Overview

The GFX100RF is designed to cater specifically to enthusiasts who prioritise in-camera processing over the shoot-now-develop-later RAW approach. It excels in the creation of off-the-peg JPEG (or HEIF) compositions, providing seamless access to crop settings, aspect ratios, and an extensive range of film simulations.

Initially, I harboured reservations. Customarily, I opt for RAW files, allowing ample time to refine the results in post-processing. Out-of-camera images have never been my preferred style. However, the design and control features dedicated to in-camera processing have ultimately won me over.

Not only does the GFX100RF serve up fantastic out-of-camera images, it specialises in harnessing the sensor’s 102 megapixel count to encourage digital zooming or cropped aspect images. In most respects, it replaces the standard zoom lens used on the typical interchangeable-lens camera, although an optical zoom will always preserve the full resolution of the sensor.

If one fully embraces the camera’s capabilities, utilising crops, aspect ratios, and film simulations, it will become addictive, Indeed, it is tempting to abandon RAW altogether, such is the quality of the processed images. However, I still like to have the insurance of being able to go to the RAW file if necessary.

None of this means that the camera is not intended for photographers who work exclusively in RAW. Sure, you won’t value many of the controls which are focused on JPGs, but you will love the extraordinary quality that this 102MP sensor is capable of.

However, while I have placed emphasis in this review on in-camera processing (which is what Fujifilm would like us to do), RAW files are there for your individual processing techniques.

The Q and X factors

The similarities between the Q3 and GFX100RF are obvious. And Fuji fans will instantly recognise the RF as a grown-up X100. I suspect both these cameras were highly influential in the design of the RF. To the Q, Fuji owes the concept of a large-sensor fixed-lens camera. While the home-grown X100 provides the perfect template for appearance, controls and handling.

Both these cameras, the full-frame Leica and the crop-frame X100, were in my thoughts throughout the test period and comparisons are difficult to avoid. So I won’t.

Buoyed by the remarkable success of the six consecutive X100 models — introduced in September 2010 and organically improved over the past fifteen years, Fujifilm is on a roll. However, faced with the proven success of the Leica Q over the past ten years, the Japanese company needed to develop a larger-sensor version of the APS-C winner. There is a decided interest among photographers in moving to full frame, so why not go one better?

The snag is that Fujifilm (sensibly) decided not to adopt full-frame. Rightly, the company decided that such a change would endanger the position of the X100 and its other cameras. Just too close for comfort. Panasonic Lumix made a similarly pragmatic decision in leapfrogging APS-C and adding full-frame sensors to its traditional MFT fare.

“There was a time when many in the industry thought Fujifilm was making a mistake by sticking to APS-C with its X Series, arguing instead that Fujifilm should commit to a full-frame mirrorless camera. Well, the company skipped right over that and went to medium format instead, and is performing exceptionally well in both segments” — Jeremy Gray, PetaPixel

As a result, the GFX50S was born in 2016, featuring a 44×33 mm “medium-format” sensor (but see the discussion on MF later in this review) with the same 4:3 aspect ratio as Micro Four Thirds. Just a lot bigger. The GFX100RF represents a natural development, and it surprises on many fronts, especially in its size and weight.

Design

This is a chunky, comfortable camera which is easy to carry around all day. I have used it mainly with a wrist strap, despite the very attractive leather strap provided, and this is a testament to its overall fitness for its role of an everyday carry — not to mention to its relatively light weight.

The camera is very similar in appearance to the X100VI, except for the missing viewfinder window at the front. This is a pity, since that window would add more balance and interest to the overall appearance. I hesitate to suggest a cosmetic dummy window, but they must have entertained the thought for a brief moment!

Whereas the X100 has always featured a hybrid electrical/optical finder, the RF relies entirely on its excellent electronic viewfinder. For me, this is fine. I never really bonded with the hybrid viewfinder and normally default to electronic view when using the X100VI. It makes things simpler. If I get rangefinder withdrawal symptoms, I can pick up my M11.

The camera sports a full set of physical controls and sturdy, well-fitting plastic doors at either end. This is an improvement on the rubber caps found on some cameras. The left-hand compartment is dedicated to the ports — USB-C (for charging and high-speed image transfer), a micro-HDMI port to connect to an external monitor, plus microphone input, headphone jack and a remote shutter release connection.

On the opposite end of the camera, the door reveals two SD card slots.

The overall build of the camera is excellent, with the cross-knurled milling on the lens and operating controls creating a stunning overall appearance.

In the box

The GFX100RF comes with everything you need to get started, even that high-quality leather rope-style strap and a UV filter. That must be a first. The lens adaptor and hood are included, unlike with the X100VI, where these items are a paid-for accessory.

The pack includes with one battery and charging cable but, as is normal these days, no charging pod. You have to rely on in-camera replenishing or buy a third-party double charge pod.

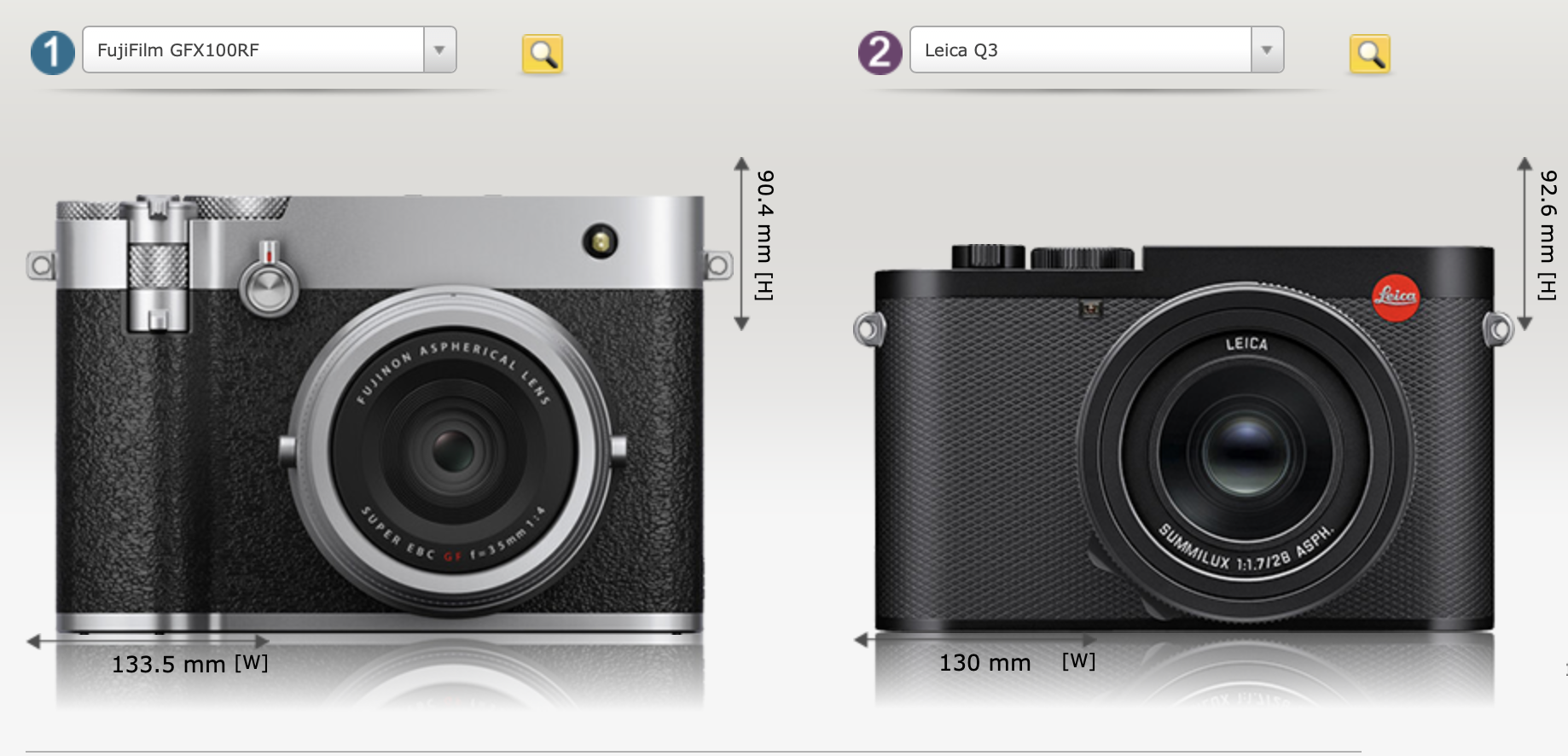

Dimensions and weight

The GFX100RF is almost identical in weight (735g) to the Leica Q3 (743g). Overall dimensions are 133.5×90.4×76.5 mm, compared with the Leica’s 130×80.3×92.6 mm. The Leica is actually slightly bigger in volume, despite the taller body of the RF. The reason is the smaller lens of the RF, which makes for a squarer profile. More on the size differences later.

I find it easier to store the RF in a bag than the Q3 because of the shorter lens (if no hood is attached). Coincidentally, if you look at the dimensions, the aspect ratio of the body is almost 4:3, to match the sensor. That’s why it looks squarish and high. The Q3 is more of a 3:2 type of guy when it comes to dimensions. Bear in mind, however, that if you fit the lens adaptor (for weather proofing or filter attachment) and the hood, the overall length of the lens is slightly longer than the Q3’s lens.

However, the incorporation of a 101.7MP medium-format sensor, with all its ramifications, truly does not add to the burden of carrying this camera. If you can manage a Q3, you can manage the RF. If you are used to the 521g X100 you’ll need to accustom yourself to the added weight, but the handling experience is very similar, and you will soon feel at home.

Physical controls

If you like the Fujifilm X100 series, you will love the concept of the GFX100RF. In contrast to many modern cameras, including Leica’s Q, this is a maximalist take on physical controls. There’s a knob, button, or dial for almost everything you would wish to adjust while out and about. In the main, the levers and buttons and dials can be customised via the menu (with the notable exception of the zoom lever).

Despite the apparent complexity, this is one of the few cameras that offers direct control over almost every aspect of operating the camera.

One glance down as you prepare to press the shutter, and you can check shutter speed (unless using the electronic shutter), exposure compensation, ISO setting, and aperture. There’s even more. A new vertical aspect ratio dial enables you to see the setting in a small window as you look down.

Control tower

While the RF loses the hybrid viewfinder of the X100, it gains several additional controls, including that prominent aspect ratio dial. On the front of the camera, the shutter button and power switch sit atop a “control tower” (my words) which incorporates the front control wheel and a lever dedicated to the crop function — demonstrating that cropping is considered a major part of the RF experience.

At the front, in the position where you used to find the old Leica self-timer, is a function button surrounded by a programmable two-way lever which uses long-pull and short-pull techniques to serve up four functions.

Similarities with the X100 continue on the top plate, with a dedicated exposure compensation dial, a programmable function button and the shutter speed dial incorporating an ISO setting window.

On the rear of the camera, there is a full complement of manual controls. The shooting mode dial is prominent and easily operated via a lever next to the viewfinder.

This is a much more sensible arrangement than the usual Fujifilm slider switch on the side of the body. The new and unusual vertical aspect ratio selector, with the exposure lock button and rear command dial, occupy the remainder of the rear of the top deck.

To the right of the tilting screen are four buttons, Menu/OK, Display/Back, Play and Drive/Delete. Above, is a joystick with its milled surface. It can be moved in four directions for scrolling and selection, or pushed for confirmation.

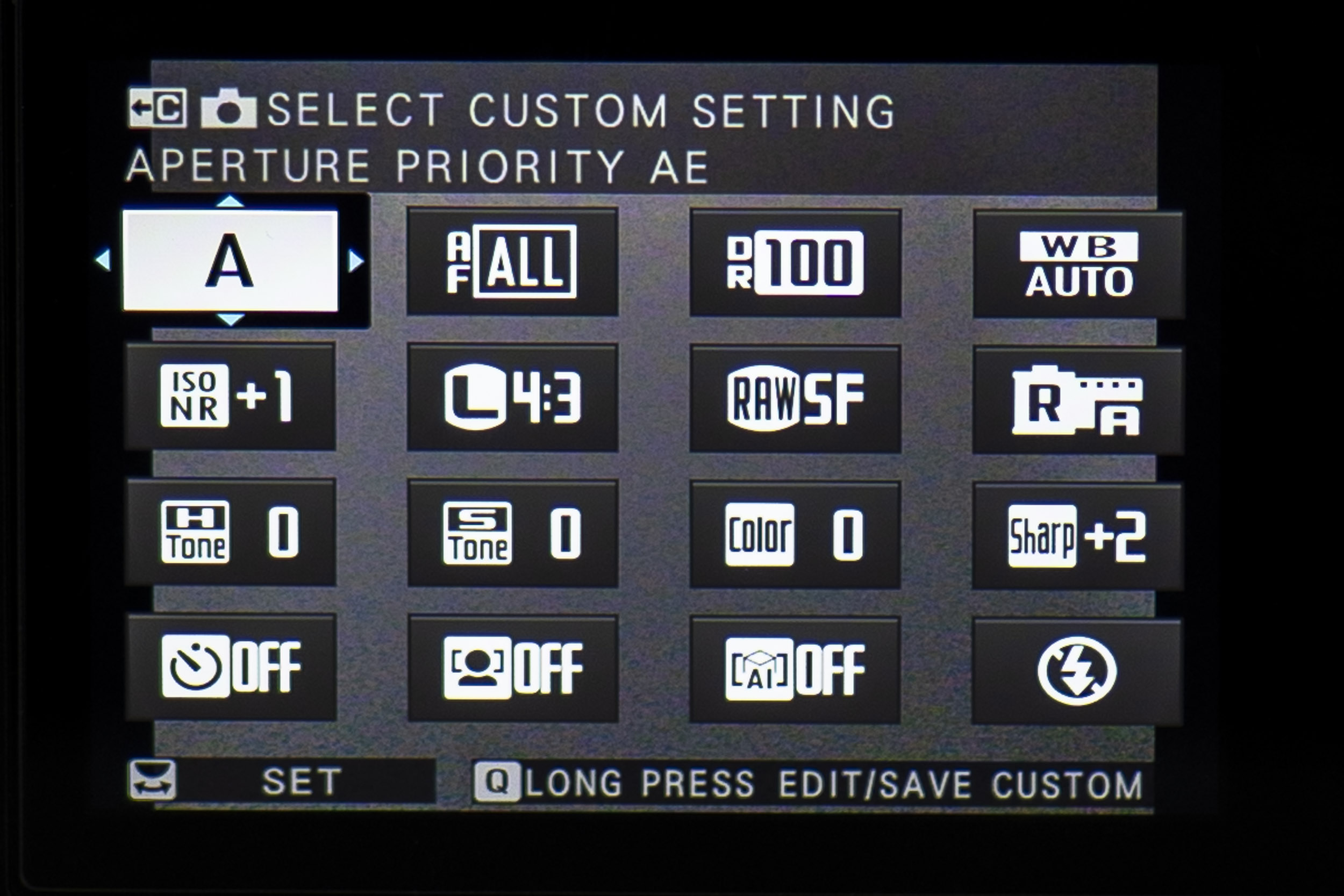

The viewfinder diopter control is large and easy to adjust, although the dial is prone to inadvertent nudging. To the far right of the rear, below the command dial, is a small Q button which accesses the Quick Menu of 16 customisable functions. After setting up to your taste, you gain rapid access to any commonly used functions that are not covered elsewhere by physical controls (see image in the Menus section).

If that isn’t enough, the menu system includes a two-page MY menu, which you can populate with yet more functions you wish to attack occasionally. I seldom found the need to meddle with this, having set up the camera to my preferences.

The aperture ring features two large round knobs to make adjustment easier. The entire control layout is typical Fujifilm and adheres to the ethos of providing a button or a knob for everything, thus ensuring that you have a complete overview of the status of the camera just by glancing down. That’s as it used to be, but is no longer, with Leicas.

The physical aspect ratio, exposure compensation and ISO dials all feature a “C” option which transfers the desired function to the rear command dial. I found this to be extremely useful, especially for direct adjustment of the aspect ratio while looking through the viewfinder.

I did miss the Leica method of programming function buttons and dials, where a long press brings up a list of available settings. It’s quick, intuitive, and effective. It certainly beats the Fuji method of ploughing through the menus every time you want to reassign a function to a physical control.

Whether you are a maximalist or minimalist when it comes to controls, is a matter of personal preference. I have long since bonded with Leica’s relatively minimalist approach and, in many ways, prefer it. However, I can also appreciate the Fujifilm approach, which imbues confidence in knowing instantly all the major exposure factors without using the screen or viewfinder.

Control problems

Levers and dials are generally smooth and precise, and the diamond milling makes it easy to grasp the control. The two control dials on the top plate sport rather sharp edges, which can be uncomfortable, although it’s a very minor issue.

The joystick, however, is rather unpleasant with its rash of tactile spots and a sharp edge which detracts from the comfortable feeling you get from the other controls.

I do not like the power switch which, as on the X100VI, is concentric with the shutter button. The power switch on the smaller camera has been criticised for being too loose and easily knocked. Fujifilm has tried to address this, with the RF lever being slightly stiffer in operation. Good.

However, this improvement is negated by the unfortunate decision to extend the lever 4mm from the front of the camera. It is too prominent, and it is easy to switch the camera on or off accidentally. Bad.

Furthermore, the forefinger sometimes connects with the power switch instead of the lower zoom lever (they feel similar, although at different heights) and I have switched off the camera many times accidentally when attempting to zoom. Muscle memory on this aspect is taking a long time to kick in.

This power switch is a design fault which cannot be correct — at least on this Mark I version — short of employing a warranty-busting metal file. Fujifilm would have done well to stick with the smaller, stubby switch of the X100VI, flush with the body, while making it somewhat stiffer in operation.

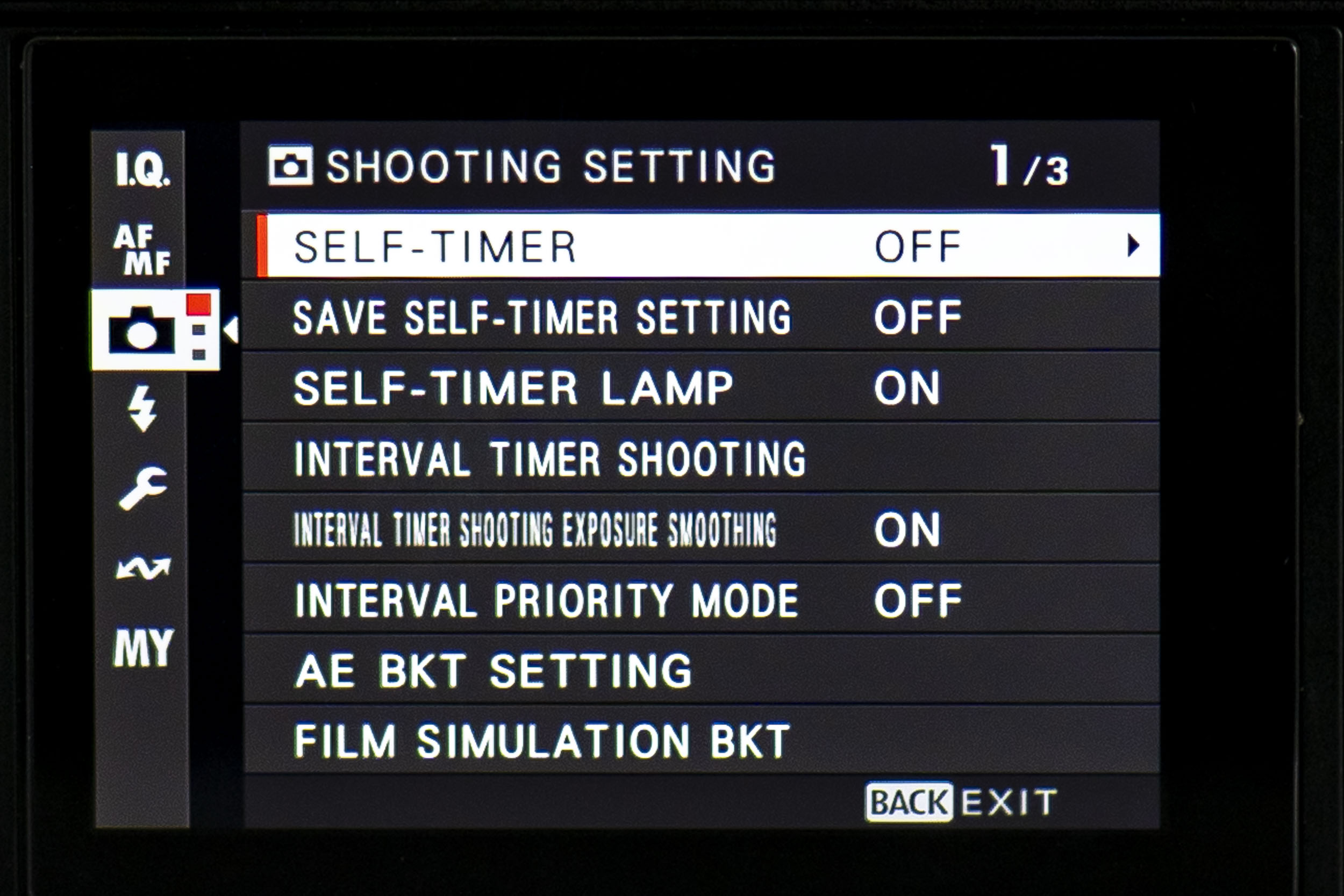

Menus

Fuji’s menus are not known for pandering to intuition. Fuji owners, especially the massive band of X100VI enthusiasts, will probably disagree. It’s what you’re used to. But coming from the clarity and simplicity of the Leica system, the Fuji menus are a shock. I’ve struggled with the menus on the X100VI, and the GFX100RF offers more of the same frustration.

My pet hate with Fuji menus is the condensed capitals. Some options are too long and, instead of using abbreviations, the designers opt to reduce the point size or adopt excessively compressed letters. Using upper and lower case instead of capital would make things easier, I believe. Although I can normally read camera menus without aid, I find it necessary to use reading glasses with both the X100 and RF.

As with any camera, nevertheless, once it has been set up, there is less need to delve into the menus for day-to-day tasks. I use the Fuji X100VI and have it set up for my needs; I seldom encounter the worst convolutions of the menu layout. The RF offers even more in the way of physical settings, so the menus represent just an occasional nuisance.

Sensor

The 43.8×32.9mm 101.7MP CMOS II sensor with 16-bit colour depth is designated as “G Format” by Fujifilm. Native aspect ratio is 4:3, as with Micro Four Thirds, and that is the setting to use if you wish to utilise the full quota of pixels at your disposal.

G Format is the same size as the sensor used in the Hasselblad X2D, for instance, and is becoming the accepted version of digital “medium format”. However, let’s not forget that historically there have been many versions, primarily based around the 120 film format.

These include 60×60 and 60×45 mm formats, and all are larger than the digital version. If you take a purist view, it isn’t really “medium format”. All I can say with certainty is that this digital sensor around 70 per cent bigger than a “full-frame” digital sensor (1,441 mm² compared with 864 mm²).

Incidentally, the sensor in the RF has the same pixel pitch as that in the Leica Q3, you just get more of them. Therefore, if you use the 45mm (35mm full-frame) crop on the RF you end up with 62MP, the same as the Q3 at 28mm. There are indeed many similarities between the sensors used in Hasselblad, Fuji, and Leica (Q3/SL), not to mention Sony cameras.

ISO sensitivity in standard output is from ISO100 to ISO12800. In extended mode it ranges from ISO50 to ISO102400. The sensor provides a useful 14-stop dynamic range.

Lens

Despite the howls of anguish over the “slow” lens and lack of in-lens stabilisation, Fujifilm made a courageous decision in opting for a high-quality but slow lens. The designers needed a really compact unit to offset the inevitable bulk of a medium-format body, and the choice of a faster f/2.5 or f/2.8 would have made the camera unwieldy for its intended purpose. The Fujinon Asperical Super EBC GF 35mm f/4 well fits the brief.

Bear in mind, though, that this f/4 lens is equivalent to a full-frame lens with a maximum aperture of around f/3.1, so in depth-of-field terms it is nearer to f/2.8 than f/4. Despite the shortcomings, the lens performs exceptionally well and is ideally suited to the camera in terms of size. If you are apprehensive about the slow aperture, remember the old Leica X Vario which had a bad press because of the slow lens, yet in retrospect we appreciate the quality of the results and have learned to live with the aperture range.

These days, too, it is always possible to bump up the ISO and denoise in post-production if light is a problem. But there is no doubt that you will miss that incredibly narrow depth of field that faster medium format lenses provide.

Stabilisation

The absence of in-lens stabilisation (as demonstrated ably in Leica’s Q3 and Q3 43 lenses) is also perceived as a major problem. But I believe Fujifilm made the right decision in trimming features and low-light performance in the interests of space and weight saving. With a faster, stabilised lens, this would no longer have been a light, easily handled camera. And please remember that we Leica users manage to take the odd acceptable photograph with M cameras, despite the lack of stabilisation. I set 1/125s as the minimum shutter speed for most of the out-and-about general photography.

Moving from these contentious issues, we can really appreciate this gorgeously crafted “pancake” lens which, remarkably, extends only 28mm from the body. The diamond milling on the focus ring is superb and exudes quality. This is a well-built, solid lens and no mistake.

The aperture ring is next to the body in usual Fujifilm style and the values are back to front by Leica standards, with the slowest aperture (f/22) adjacent to A (auto). I find this rather awkward since, if I’m switching from A to a fixed aperture, I’m usually reaching for f/5.6 than f/22. Think of it as like driving on the “wrong” side of the road. You get used to it, but it doesn’t come naturally for experienced Leica users.

Apertures are adjustable in 1/3 stops, and the ring sports two substantial knobs to aid adjustment. Without these protrusions, changing aperture would be challenging.

While this is a wonderfully compact pancake-style lens, it is not weatherproofed and the front element is exposed. Worse, it extends a further 3mm when the camera is powered. There is no way to fit a filter or hood to the naked lens. This is also the case with the similar set-up on the Fujifilm X100VI.

Adapter ring

Fujifilm gets around this problem by providing an 11mm-wide adaptor ring which allows a filter, hood, or both to be fitted. While it’s tempting to use the camera without this adapter, mainly because the lens is so incredibly small, few owners will be prepared to risk accidental damage, so the adapter has been a permanent fixture.

Thus, the lens, which starts so amazingly small, expands to a depth of 43mm when the adaptor ring is fitted. Adding a filter increases the length to 46mm and attaching the bayonet hood takes the length to 60mm, exactly twice the size of the lens itself.

Despite this, it is still an acceptable size for a medium-format f/4 lens. Imagine the size if Fuji had constructed an f/2.5 lens. The deep hood is very effective and is recommended for very sunny conditions.

Fujifilm X100VI owners, who have to buy the adapter ring and hood separately (around £70), will be jealous to find that the GFX100RF comes complete with the adapter and hood — and even a gratis UV filter. It’s the complete kit, and it’s necessary if you don’t want to risk damaging the front element of the lens.

The lens is constructed of ten elements in eight groups, including two aspherical elements. The leaf shutter is built into the lens, similar to the design of the Leica Q series, enabling the lens to be embedded in the camera to reduce external dimensions. This is a significant benefit compared with interchangeable-lens cameras such as Fujifilm’s other medium-format offerings.

Quiet leaf shutter

The mechanical shutter is available up to 1/4000s, while an electronic shutter allows two further stops of adjustment up to 1/16000s. A feature of the camera is that the leaf shutter is hushed; it is probably the quietest shutter I have experienced. I does not of itself cause camera shake.

Minimum focus distance is 20cm. The lens can accept 49mm filters when using the included adapter ring — the same as the X100VI.

The camera also features a built-in four-stop ND filter, offering greater control over exposure in bright conditions. This can be activated by using one of the physical control levers, so it is always available.

The focus ring has an additional option when the camera is set to AF mode. It can be assigned to two functions — white balance or film simulation.

Fujifilm’s compact lens, as with Leica’s Q3 lens, relies on mathematical software distortion correction and this is now a widespread feature of lens design. It’s something we have grown to accept and don’t give it a second thought.

EVF and screen

Although the OLED electronic viewfinder offers the same 5.76 million dots as the unit in the Leica Q3 and SL3, it just feels more involving. It is very subjective, but this is a magnificent finder. While it isn’t up to the standard of the outstanding 9.44 million finder in the Fujifilm GFX100 II, it offers an exceptionally sharp and detailed image which provides an immersive impression of the scene.

The eye cup is substantial and comfortable, even for wearers of glasses. The large diopter thumb wheel to the left of the viewfinder is easy to adjust from -5 to +3, although I did find that occasional it moved inadvertently because it is right on the edge of the body.

The 3.15in rear screen monitor has a resolution of 2.1 million dots. Touch mode operates in shooting and playback mode, but there is no touch facility for menu adjustment. That’s sensible because you’d need fingers as dinky as Korean chopsticks to make changes.

The screen tilts up and down, similar to the Q3. However, implementation is better in that the screen on the RF can be pulled out so that there is a gap of 20mm between the top edge of the screen and the camera body. This makes low shots, in particular, more convenient than on the Q3, where the top of the screen cannot be moved away from the camera body.

Another significant difference between the two cameras is that the screen of the RF is fully integrated and looks part of the design, almost undetectable when folded away.

On the Q3, by comparison, the screen stands proud of the body when folded away. It looks more like an afterthought, which I suppose it is because a folding screen was not implemented in the original Q3 body design.

One way in which the Q3 does score heavily is in the automatic transfer of the image from the EVF to the screen as soon as it is folded out. This doesn’t happen with the RF, and it is necessary to manually adjust the display so you can compose the picture. It can become a chore if you normally prefer to shoot with the screen disabled. Full marks to Wetzlar on this one; it’s a brilliant idea.

Battery and storage

Battery life of the GFX100RF is excellent. The camera uses the same large 2200 mAh NP-W235 unit as the GFX ILC cameras.

Fujifilm claim up to 820 shots per charge. I was able to top 500 without trying. Mostly, however, I was using the EVF only with auto power-off set to two minutes. One rider, though, is the tendency for the camera to switch itself on or off unbidden.

It is far too easy to toggle the power lever when storing the camera in a bag, with predictable results. If this happens, and you have a soft-release button in the shutter thread, you can run down the battery while the camera is in the bag. In theory, even if the camera is left switched on, it should power down after a couple of minutes. But it appears to wake repeatedly, probably because the power switch can be nudged easily while the bag is being carried.

Despite being fully aware of this danger, I frequently pull the camera out of the bag, only to find that the battery is flat. This is a real and constant danger and means that I always carry a spare battery, despite the large capacity.

It is a pity that Fujifilm doesn’t provide the opportunity to select a battery percentage display. In common with most cameras, the little battery icon with bars can be misleading. Once the first bar drops, the descent can be rapid.

As with most modern cameras, in-camera charging is the only option unless you buy an external charger pod (either from the manufacturer or from a third-party supplier). I ordered a K&F Concept double-battery charger pod for £39 from Amazon, and it has performed well1. As a bonus, it came with two NP-W235 after-market batteries. Incidentally, both batteries came with a plastic clip-on protector to keep the unit safe while in storage.

Storage

The GFX100RF is a grown-up camera when it comes to data-storage options. No flappy doors under the camera, or slots next to the battery. Here we have a proper, well-engineered side door with two SD card slots. Since there is no internal storage in the RF (and nor is there in the Leica Q3), the extra slot can be a lifesaver.

The slots accommodate SD, SDHC, and SDXC memory cards. Both UHS-I and UHS-II bus interfaces are supported.

During the test period, I set the camera to produce compressed RAW (Fujifilm = RAF) files and JPG. The compressed RAW files were generally 72MB in size, while JPGs ranged from 54 to 24MP depending on crop or aspect ratio. This is a lot of storage, of course, and you need to make adequate provision. Fortunately, mass storage is now relatively cheap, and I don’t see the size of the files as a major problem.

Tricks and treats

Fujifilm has gone to great lengths to encourage users to specialise in in-camera processing. Digital zoom, aspect ratio selection and film simulations are so easy to manage that it would be churlish not to take full advantage of the options.

Every aspect of the GFX100RF, including the control setup, is designed to complement the task of in-camera processing. While this camera produces outstanding and malleable RAW files if you wish to do your processing, it is a master of producing ready-to-use material which needs little, if any, adjustment. In many ways, the choice and quality of output is reminiscent of modern smartphones, but of course with exponentially greater resolution.

1. Digital zoom

What was once unthinkable and only for amateur point-and-shooters who didn’t know better, digital cropping is now highly respectable. Even Leica’s lens guru, Peter Karbe, is a fan of combining high-resolution sensors with outstanding wider-angle lenses to zoom in digitally. Within reason, of course. Let’s not get too carried away because an optical zoom will always win.

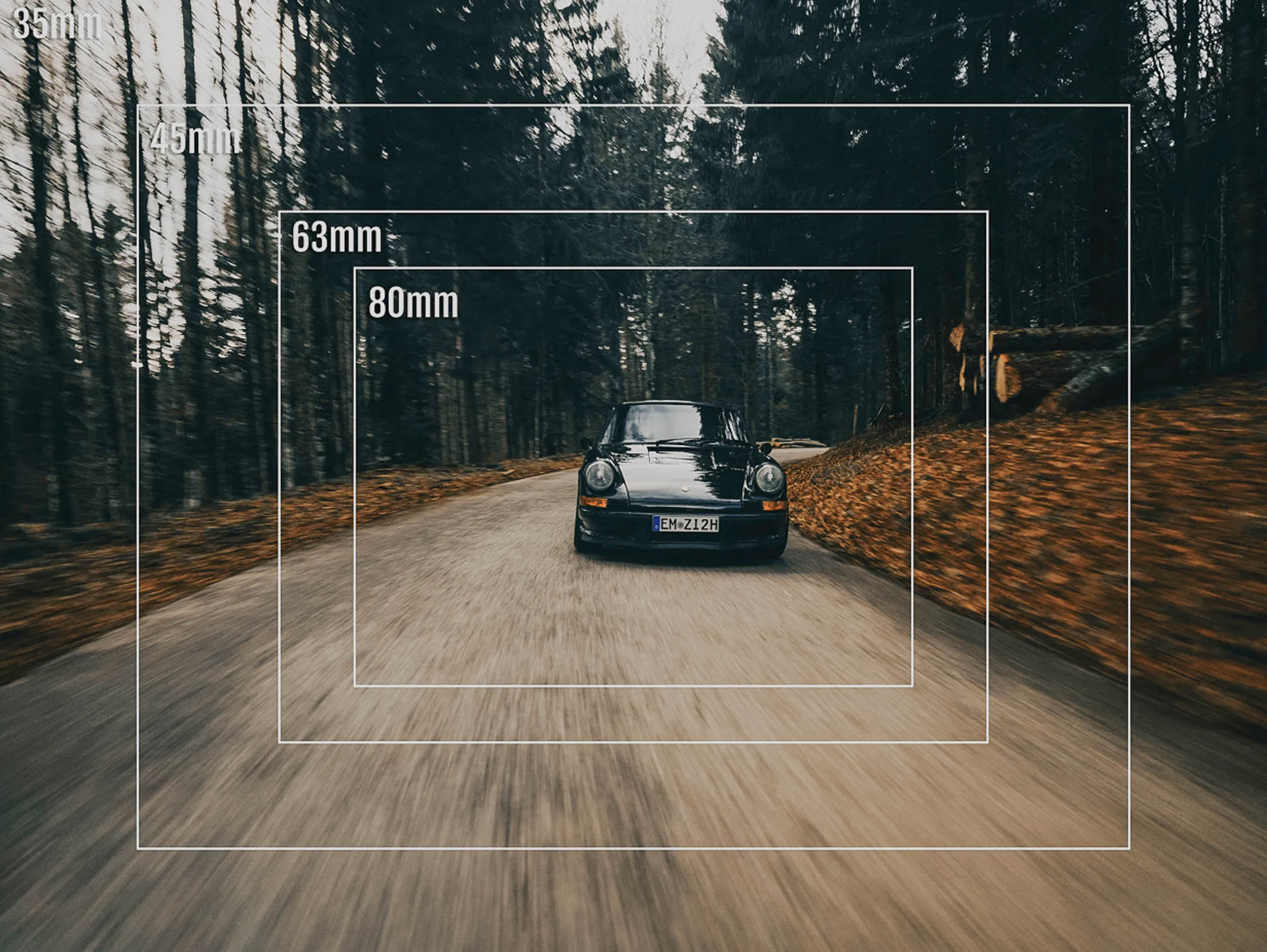

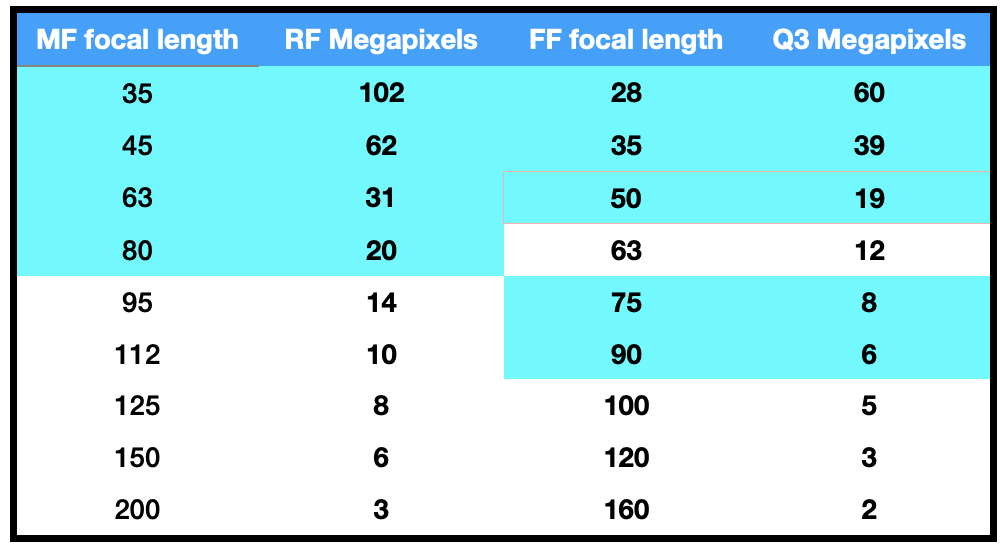

As sensor resolution has expanded, it is increasingly possible to produce crops that offer the same pixel count as a high-end full-frame camera of just a few years ago.

With 102 million dots at its disposal, the RF provides 62MP at 45mm, 31MP at 63mm, and a respectable 20MP at 80mm. All are more than impressive when compared with, say, the 24MP sensor that is still popular on cameras such as the Panasonic S5II and Leica SL3-S.

The RF produces outstanding results at 80 (63mm)mm, and it is surprising that Fujifilm did not include at least one extra set of framelines, to 90 or 100mm. It’s telling that the Leica Q3, with its 60MP sensor, provides 90mm framelines (roughly equivalent to 105 on the medium-format Fuji) and the company stands by the resulting image quality from the 6MP file.

I reckon you can zoom-in further, certainly up to the full-frame equivalence of 90mm, while still retaining usable quality for small prints. In my crop-to-zoom tests of fixed lens cameras last year, I found that image quality even at the equivalent of 135mm was still acceptable, though inferior of course to optical zoom. But needs must… and cameras such as the GFX100RF make excellent all-round travel companions unless you really must have long optical cover. Quite extreme crops are still usable, although obviously not as good as optical zoom images.

Using crop mode is simple. The dedicated crop lever on the front of the camera (beneath the power switch) toggles between the four options (35/45/63/80) and operates on any selected aspect ratio, with 4:3 being the standard ratio for the MF sensor. Furthermore, there are three ways of viewing the crop.

1 The traditional rangefinder style, with white frame lines. The surrounding area is visible, as with, say, a Leica M, and is similar to the crop-view options on the Q3.

2 Second choice replaces the frame with a shaded, opaque surround. Again, the surrounding area is visible, but darker than the frame.

3 Final option is a magnified image to fit the full frame. This is great and immersive, but it can be misleading if you forget you are using a crop mode. The only indicator is a small focal-length indicator in the screen/EVF sidebar (if you have it selected; otherwise you will not be aware).

The one thing you will not see in the viewfinder is the hybrid electronic/optical view, which is one of the main USPs of the X100VI. I don’t miss it, though, and prefer to work with the excellent electronic display.

Despite the camera manufacturers’ new love affair with cropping, we should not lose sight of the benefits of longer lenses in terms of greater subject separation (even at narrower apertures) and full-sensor utilisation at any focal length. They still have their place, and that’s why interchangeable lens cameras are still the most popular. However much you crop from a 28mm wide-angle lens is still a 28mm lens, with all the drawbacks that entails.

That said, fixed lenses, spearheaded now by the GFX100RF and the Leica Qs (and ably supported by their APS-C brethren), do offer an acceptable alternative for travellers who wish to cut down on weighty gear.

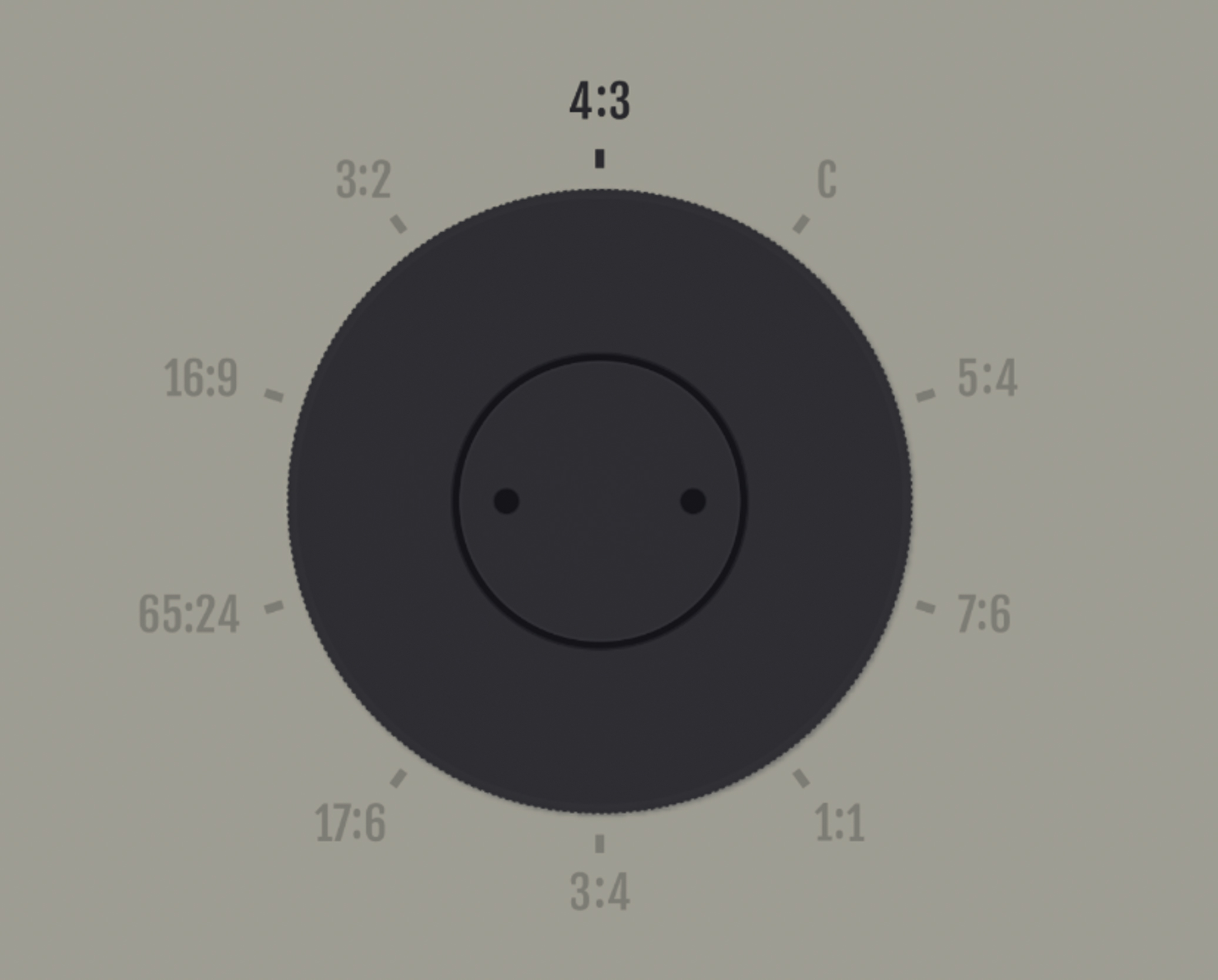

2. Aspect ratios

Users of many generations of the Panasonic LX100 and D-Lux cameras will be familiar with the physical aspect ratio switch on the lens. However, the RF ups the game with direct access to no fewer than nine aspect ratios. The new vertical selector wheel on the top plate, with the chosen ratio showing in a small window at the top, is a much better implementation than we find on the D-Lux 8. It becomes yet another glance-down setting that is always visible.

In addition to the native 4:3 aspect of the sensor, you can choose eight other ratios: 5:4, 7:6, 1:1, 3:4, 17:6, 65:24, 16:9 and 3:2. At first, I was sceptical about all this (as I have been in the past with the four options on the D-Lux), but I soon came to love playing with the settings. They can be useful in visualising a scene and add to the fun of using the camera, even for RAW shooters.

The vertical selector dial is rather fiddly to adjust, but fortunately, there is a ‘C’ setting which allows the selection to be transferred to the rear command dial.

If I had the choice, I would remove the physical control and rely on the command dial for adjustment. It’s quicker and more intuitive because you see what you are getting, rather than envisioning the result from a set of numbers.

As with the crop mode, the chosen aspect ratio is indicated on-screen by a small icon, this time in blue, if you have it visible. As you change ratios, the viewfinder, or screen image changes accordingly, with the image on a black background.

Aspect ratios are indicated in the viewfinder or on the screen using three options:

- White framelines

- Frames surrounded by an opaque background

- Frames surrounded by a black background.

After some experimentation, I opted for the third option.

The aspect ratio function is useful even when shooting RAW. For instance, choosing 16:9 enables accurate framing for that aspect and, when processing, the cropped image appears first in Lightroom. It’s a good guide, but it can be overridden; the full image is always available if you’ve cropped in a little too far2. Fuji has done a good job in integrating the crop and aspect ratio functions with RAW files.

However, aspect ratios are not available if you are shooting RAW only. If, therefore, you wish to see the aspect ratio initially in Lightroom, you must also shoot a minimum resolution JPG or HEIF.

A crucial factor in using aspect ratios is that the massive sensor in this camera produces high-resolution images that are genuinely useable at almost any aspect. For instance, the 65:24 panoramic aspect ratio still creates 50MP images — twice the resolution of, for instance, a full-frame image from a 24MP full-frame camera such as the Leica SL3-S. This became one of my favourite aspect ratios for landscape photography, where sky and foreground can often dominate the scene. Fujifilm tell us that this aspect ratio is based on the TX1 camera, and it is certainly the nearest we can come to that in 2025.

Fujifilm X100VI owners are less fortunate in their aspect ratio implementation. For starters, there are fewer choices (3:2 native, 4:4, 5:4, 1:1, 16:9). But the only way to change the aspects is to delve into the menu (or Q menu) and change the image quality. For every aspect ratio, you have to scroll through S, M and L image quality, and it is easy to choose the wrong one accidentally. On the good side, you can assign the image size option to a function button, enabling selection from the command dial.

The RF excels in its options, however. After totally ignoring aspect ratios when using the D-Lux 8, I have come full circle and thoroughly enjoy playing with the many options that can be conjured up on the RF at the flick of a dial.

3. Film Simulations

Fujifilm has a strong reputation for its film simulations. If you are a JPG shooter, the GFX100RF offers a wide range of options to choose from, mostly replicating the results from Fuji films of the past. There are twenty different modes, including filters, and it’s great fun to play with them. Again, I started off sceptical (as I did with aspect ratios), but, as I experimented, I thoroughly enjoyed selecting a simulation for the JPEG file. The same options are available on the Fujifilm X100VI.

Click here to see the above image in all 20 simulations

A neat touch is the ability to assign the lens control ring to these film simulations (it reverts automatically to focus when you select MF). This setting, which mimics that on the X100VI, provides a quick method of changing the appearance of the JPG file. It works well, although there is a tendency to overshoot, and you need to slow down and be more precise in your selection. Note that the only other available option for the lens control ring in auto-mode is for adjusting white balance.

Many of the images in this article were shot using the VELVIA/Vivid simulation. They are certainly vivid, which is not everyone’s cup of tea, but they demonstrate the JPG processing for which Fujifilm is renowned. I would dial down the saturation a tad, but readers will understand this and consider the overall image quality. For a less saturated effect, PROVIA is a practical alternative.

The choice of treatments (for in-camera processing) is extensive, so there should be something for everyone. REALA ACE for colour is currently fashionable, while ACROS for black-and-white, with its red, yellow and green filter effects, is gaining in popularity among Fujifilm shooters.

Here is a list of the full ready-made simulations. You can, of course, create your own bespoke JPGs, but the off-the-peg selection is very comprehensive and fun to use. Nevertheless, if you shoot raw (RAF) in tandem, all your options are open if you decide you don’t like the camera output.

• PROVIA/Standard

• VELVIA/Vivid

• ASTIA/Soft

• Classic Chrome

• REALA ACE

• PRO Neg.Hi

• PRO Neg.Std

• Classic Neg.

• Nostalgic Neg.

• ETERNA/Cinema

• ETERNA BLEACH BYPASS

• ACROS

• ACROS + Yellow Filter

• ACROS + Red Filter

• ACROS + Green Filter

• Black & White

• Black & White + Yellow Filter

• Black & White + Red Filter

• Black & White + Green Filter

• Sepia

No one does this film simulation thing better than Fujifilm, and I can guarantee hours of inoffensive fun if you use the GFX100RF and are a fan of in-camera processing. Even if you are a firm RAW addict, as am I, playing with the Fuji options is educational. Of course, most manufacturers offer off-the-peg JPG recipes, but Fujifilm just adds an attractive touch of showmanship.

In addition to normal and universal JPG output, the camera can handle other standards, including HEIF (High-Efficiency Image Format) which, although less universally acceptable, stores a greater level of detail. Using Lightroom (I haven’t checked other software) it is possible to retrospectively add the Fujifilm simulations to any RAW file.

Final word: The majority of images in this article are straight-from-camera and have not been processed in any way. This is a first for me. I generally shoot RAW and agonise over PP, worrying about consistency and condemning the camera unfairly as a result of my bungling. What you see here (mostly) is pure Fuji, there is nothing that cannot be reproduced effortlessly by any RF owner, however inexperienced.

Operation

Handling

The GFX100RF is a solid, squarish camera which feels really good to hold. I don’t mind the extra height when compared with the Q3. In some respects, the squarer format makes the camera even easier to balance.

The medium-sized bump at the front helps the grip, and I had no burning urge to add an accessory grip (even if one had been available). This is unlike the Leica Q, which lacks any form of grip, and where a hand- or thumb-grip makes a sensible addition.

Designing a thumb grip for this camera is a challenge because of the siting of the aspect ratio dial and the shooting mode switch. Haoge produce one already, although it has been out of stock for some time. I will buy it at the first opportunity (it’s on order…).

Having spent the last ten years with various iterations of the Leica Q, I found the RF to be just as easy to handle. It has more sharp corners than the Leicas, but is comfortable to hold. As I mentioned earlier, I used a wrist strap most of the time because I think this type of fixed-lens camera is easier to handle in this way. I tried the (excellent) leather rope strap supplied by Fujifilm, but found the two-point fixing overkill for the size and weight of the camera. Instead of draping the camera around my neck, I store it in the Billingham Pola Stowaway bag. Your preference may differ.

Again, though, this is an opinion — I prefer wrist straps in general — but you have all the options. Note that (in typical Fujifilm fashion), the strap lugs contain shims which reduce the size of the hole. It’s impossible to thread Peak Design anchor links which permit quick strap changes (including changes between neck and wrist straps). It even defies the dental floss trick, which I demonstrated in 2023. There are ways around this, mostly involving using brute force with a screwdriver to eject the shims. I haven’t tried in case it affects the warranty.

The body is clad in a faux-leather-look plastic, which is unyielding and can become rather slippery in hot conditions. It is the same material as the body of the X100VI and other Fujifilm cameras, but the more tactile “leather” cladding of the Q3 is both more attractive and more practical.

A small additional point: The RF is well-balanced and, even equipped with adapter and hood attached, sits satisfyingly upright on its bottom, with no tendency to tilt forward because of the weight of the lens. The bigger, heavier (and, admittedly, faster) lens of the Q3 upsets the balance of the camera so that it tilts forward. It’s one of my pet hates although, in the great scheme of things, a minor irritant. It’s probably just my OCD.

Focus

Throughout my time with the RF, I used the traditional centre-spot focus because it’s something I prefer after many years with rangefinders. I find it quicker to focus on the subject and then recompose the frame3. Using this method, the camera locks on to focus quickly, but not as quickly as, say, the X100VI. I experienced no problems with hunting, except in extreme low light.

However, the RF comes with the usual complement of focus options, including single point, frame, zone, multipoint and subject detection — including the useful face/eye options and intelligent hybrid AF. The camera uses hybrid contrast/phase detection focus for best results in most conditions. AF is generally quick and precise in any mode. It feels very much like the X100VI, although the APS-C shooter ought to be faster. With a medium-format sensor, the readout speeds and all the associated technology tends to be slower than with smaller sensors. However, this was not really noticeable when using the RF.

For aficionados of focus-and-recompose operation, a wandering focus point is a major irritant. This is usually caused by nudging the joystick (or four-way pad) when handling the camera. The focus point always seems to move to the corner of the frame, where you fail to notice it, in my experience. But Fujifilm has the answer — and it works like a dream.

The convenient operation lock feature can be customised to include (or exclude) as many controls and options as you wish. For instance, since the joystick is the culprit in the wandering focus point, you can tick this in the lock menu. Then, when lock is enabled, the joystick cannot move the focus point. The control can still be used when navigating menus, however. A press on the joystick will unlock its functionality if needed, and a second press will lock it again.

Leica has fought to the death to deny us similar sensible functionality in its cameras, although you can now restore the focus point to the centre with a button press. Fujifilm is well ahead, here, and you would be surprised how important it is to have a reliable focus lock.

Note that the Fujifilm X100VI has similar functionality, which makes it so much more satisfying to use.

Image quality

There is no doubting the image quality of the GFX100RF. It is as good as it gets with modern consumer cameras. As mentioned in the sensor section, the RF uses the same sensor technology as the GRX ILS cameras and is “very similar” to that used in the Hasselblad X2D and Sony full-frame sensors (not to mention the Q3). Heretics suggest one and the same, with a nod towards Sony.

In the past four months with the GFX100RF, I have been astonished by the full-frame image quality and the resolution. While crop to zoom is a delight on the Q3, it goes to another level on the GFX100RF because of the sensor’s greater pixel count. The files shown here on this web page do not do full justice to the sensor; all our images are compressed to 500KB before upload.

Camera shake is more of a problem on larger sensors, and this highlights the absence of IBIS or OIS. However, the leaf shutter (similar to that in the X100VI) is extraordinarily quiet and smooth, thus removing one big cause of camera shake. And, of course, choosing a slightly faster shutter speed also helps reduce shake.

As you will see from the captions to these images, I erred on the side of faster shutter speeds, just as one does with a Leica M11. Life before electronic stabilisation. I have read other reviews where the (younger and steadier) testers have achieved good results with hand-held shots at 1/4s. But I (not to mention many Macfilos readers) can’t accomplish that.

While strong light is not so much of a problem with the RF as it can be with, say, the f/1.7 lens of the Q3, the RF is admirably served by the inclusion of a four-stop ND filter, similar to the X100VI. Operation can be set to a physical control so that it is always available without ploughing through the menus.

Low-Light

With its f/4 lens and lack of stabilisation, this camera is not the strongest contender in low-light performance. If you are using auto ISO, the algorithm has a tendency towards aggressive ISO settings to preserve perfect exposure — often bumping up to the highest available level (as I had a ceiling of 12800 set for most of this test).

In most cases, in low-light situations it is preferable to set ISO either manually or by limiting the top setting to, say, 6400. Then let the 14-stop dynamic range take the strain. The recovery from underexposure, particularly in RAW files, is outstandingly good. So, by underexposing by a stop or two and then recovering the detail in post, you can achieve greater levels of detail.

Incidentally, the ISO setting dial in the shutter-speed dial is easy to adjust if you wish to fix the value physically.

Since the lens is very sharp even at f/4, you can take advantage of full aperture in most low-light situations without compromising sharpness. And the depth of field is therefore greater than if you are succumbing to the temptation to us a faster lens to gather more light, which means a correspondingly narrow depth of field.

Stabilisation would undoubtedly be an advantage in low-light situations, enabling lower shutters speeds and lower ISO. In ideal circumstances, the ISO output from this sensor is remarkably clean. However, the Leica Q3 is a better bet for low-light photography, if only because of its fast f/1.7 lens, notwithstanding the above remark about depth of field.

Rolling shutter

The notorious rolling shutter effect is a hazard when using any electronic shutter. While the RF’s electronic shutter up to 1/16000s is well capable of freezing motion in most circumstances, the line-by-line readout time can cause the subject to change form. By and large, it’s a rare occurrence, but is present on most electronic shutters. However, medium-format sensors are more prone than smaller sensors.

The RF elevates rolling shutter to an art form. Eventually, I turned off the hybrid shutter and relied exclusively on the fast (1/4000s) leaf shutter. After all, this camera is not intended for photography of fast-moving subjects, and 1/4000s (which is one stop faster than, say, the Q3’s 1/2000s ceiling) is good enough for most general purposes.

Incidentally, you cannot avoid rolling shutter even if you fix the speed to 1/4000s on the physical dial. For some reason, provided the hybrid operation is enabled, the camera will select the electronic shutter at 1/4000s. This was the case with the example below. Before taking the shot, I was aware of the rolling shutter problem and deliberately set 1/4000s on the dial, assuming this would force the use of the leaf shutter. Wrong.

Target audience

The large-sensor wide-angle fixed-lens compact market is growing by the month. Since I took delivery of the GFX100RF, Sony has re-introduced its less-than-successful RX1, with tweaks that it hopes will increase market share. And established smaller fixed-lens cameras such as the Ricoh GRIII and Fujifilm X100VI are in constant demand.

Medium format a big draw

But just who is the RF aimed at?

Existing Leica owners are unlikely to defect to the RF, despite the attractions and novelty of the medium-format sensor. Many are locked in to the Leica system, owning an M or an SL in addition to a Q3 or Q3 43.

Yet, there are many photographers out there who desire a high-resolution fixed-lens camera but cannot bring themselves to buy (or afford) a Leica. The 102MP sensor in this new “compact” is undoubtedly a big draw, since it gets one up on the Leica for less money. It’s the cheapest way into digital MF.

I also see a great potential among the hordes of X100 owners who have been eying Leica’s success with the Q series and are ready for a move up in the world. With such a large (expensive) sensor, the RF is even more of a niche product than the Q, and it will never sell in the same quantities as the X100. However, it could well become the most successful medium-format camera in the range.

For the moment, above all, the GFX100RF is unique and that alone will attract buyers. At three times the price of the X100VI, it is no impulse buy, and owners of the APS-C little brother will have to dig deep in their pockets. All the signs are that the GFX100RF is selling well, and I think the camera deserves to succeed.

In the United Kingdom, the GFX100RF sells for £4,699, including 20% tax. Average price in Europe is €5,499 (including tax) while the camera sells for $5,399 pre-tax in the USA. In comparison, the Leica Q3 costs £5,298 | €6,250 | $6,735.

Conclusion

My journey with the RF has been fascinating. It is my first digital medium-format experience and there was a steep learning curve. The reverse crop factor, for a start, is against everything I’ve been used to, in a world where full-frame is assumed to be just that, the biggest.

The image quality of this 102MP sensor is exceptional. The camera produces immaculate out-of-camera images with rich colours and high definition. However, you have to remember that at the current level of technology, a medium-format sensor is not a speed demon.

Stick to slow or static subjects and the RF offers superb results. It is outstanding for landscape, architectural and street photography and the effective crops (to a modest 80mm, or 63mm in full-frame terms) are eminently usable. You can go further, and that’s for sure.

Embracing the Fujifilm film-simulations, which are so much more entertaining than the usual offerings by camera manufacturers, is an act of faith which is well rewarded. And the comprehensive set of aspect ratios adds an element of fun to general photography, while preserving great image quality.

Rewarding

I’ve enjoyed the camera so much that I will keep it in my stable for the foreseeable future. It is fun to use, and rewarding to own. While I possess a Q3 43, I no longer have a Q3, so the RF fills the requirement for a genuine wide-angle fixed-lens camera. Apart from some quibbles over the control functionality (especially the egregiously unpredictable power switch), the RF represents something of a triumph for Fujifilm.

Not only is the GFX100RF unique, it represents almost a conjuring trick in squeezing such a large sensor into a relatively compact and light body. It’s definitely a camera you should seriously consider owning. It’s a medium-format camera in full-frame clothing, and that says it all.

More reading

Here are some useful links relating to the GFX100RF. For an in-depth assessment of the camera, including lens performance and image quality, we recommend Sean Reid’s informative website. It is a subscription-based service, but well worth the cost. Sean, along with Jonathan Slack, is a valued Leica beta tester. Fuji enthusiast, Jonas Rask, provides a detailed review of the camera from a Fuji perspective.

All images in this article are the copyright of Mike Evans and Macfilos.com unless otherwise stated. None of the images may be downloaded or used without written permission.

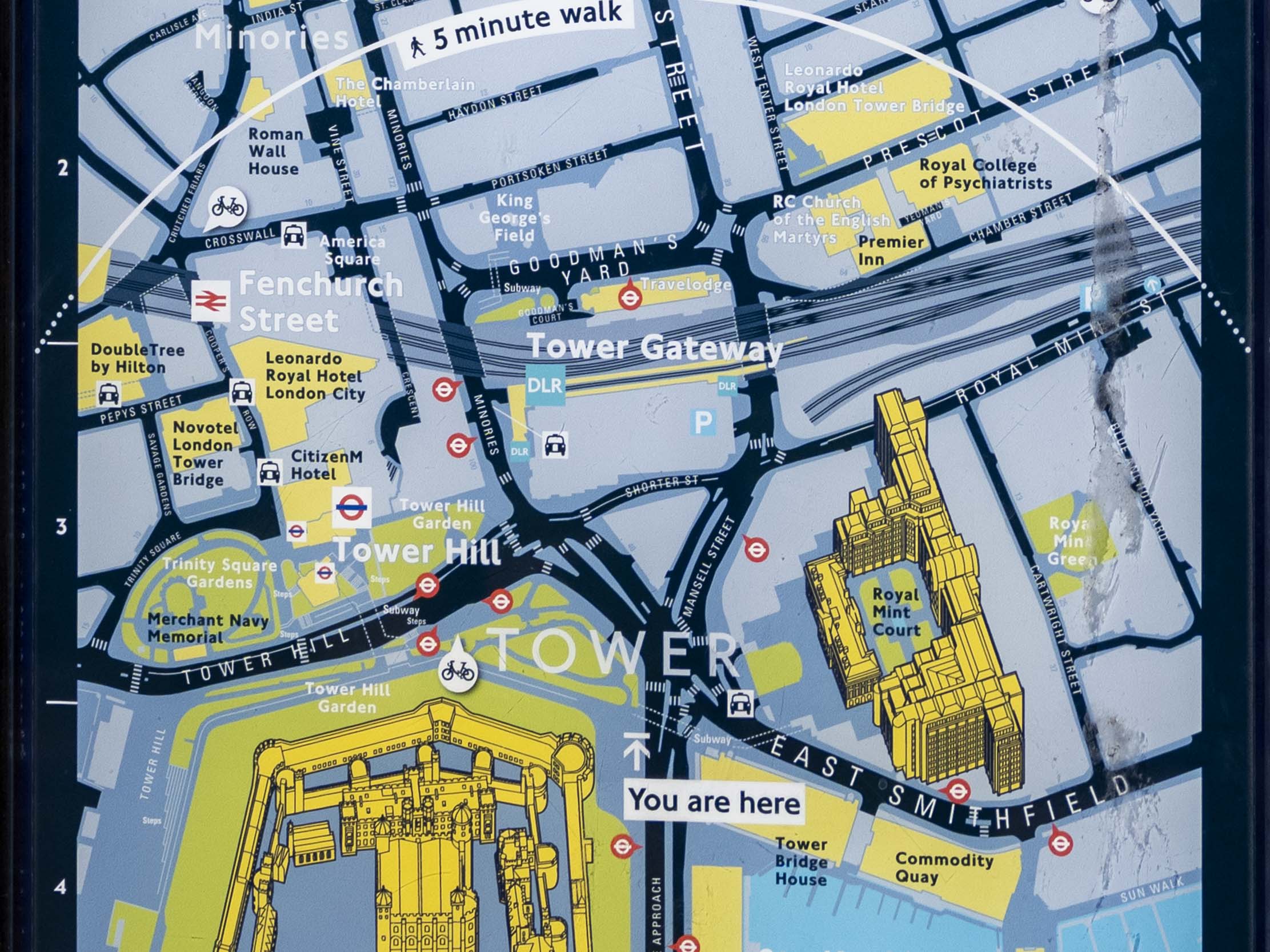

We bought this camera with our money at full recommended price. It was purchased from Chiswick Camera Centre, an old-established family photographic store in West London (there aren’t many of them left, and we like to support them…).

Click here to see further images and a gallery of film-simulation examples

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

- If you purchase from Amazon using this link, we could receive a small commission to help with our running costs. ↩︎

- If you shoot JPG only, of course, there is no going back from a crop or aspect ratio. That’s why a side-car RAW file is always useful to have. ↩︎

- This use of focus and recompose is a sore point. While many experienced M users adopt this method with AF cameras, many experienced photographers hate the idea. It’s all a matter of personal choice, but I just don’t like to see focus points wandering all over the frame (except when using the face or eye-detect functions). ↩︎

Dear Mike,

I must apologize as I have just now posted in the comments relating to your Fujifilm GFX100RF review but somehow inserted that post among those of other readers submitted on August 18th. I draw attention to my clumsy action as otherwise you might not get to see my post! Meanwhile, thank you for this great site that I have only recently discovered and spent much time reading today. Thomas

Thanks again. I did reply to your original comment, so the system is working. I am glad you enjoy the site. It’s one of the very few non-commercial magazine-style blogs of its type and we have a loyal band of contributors and readers. As you discovered for yourself, we often buy own own equipment for testing and are not beholden to any manufacturers, even Leica.

Mike

A very thorough and enjoyable short review Mike. I love the 65:24 aspect ratio but can apply it easily enough in post processing. The SL3 offers a 3:1 ratio but don’t believe that’s available on the Q3 models. Down the track Fujifilm have the option to add a more affordable 50MP version of the GFX100RF in much the same they have done with their medium format camera bodies. I’ve yet to try the Leica looks but I tend to shoot RAW only.

Thanks Tom. You are the only person who has described the review as “short”, which pleases me. All 10,600 words of it.

I agree that any aspect ratio can be applied in post — I have a stock of custom ratios in Lightroom, in addition to the standard fare.

However, having aspect ratios so easily to hand does help in composition. It’s a guide, and I soon became addicted. I am currently back on the X100VI and really miss the easy aspect ratios. It is such a fiddle to change that I seldom do.

Mike

Hi Mike,

I enjoyed your review. I can see how it could replace your Q3. I hope to get my hands on a new Hassy in the not too distant future and experience the medium format world for myself.

Thanks for your review!

Mark

Thanks, Mark. I found my brief foray into “medium format” (Jono likes me to use quotes because it really isn’t, in his book) entertaining and instructional.

I would like to try Hasselblad but not sure if I can get my hands on a rig without paying for it! That said, though, a Hassy or GFX100 II is probably more right than I want to carry around.

Glad you enjoyed the review.

Mike

In my view, it is a medium format camera. Even B&H photo calls them medium format. It is medium format in the mirrorless camera world!

I agree it is what is generally accepted now as medium format. It’s the same as the GFX and Hasselblad at least. But Jono’s point on historic formats is worth mentioning.

Well, even Leica called the Leica S a medium format camera, and the Leica S with its 3:2 aspect ratio had even less to do with historic formats used by medium format film cameras. It makes sense in my opinion to call them medium format cameras.

Mike what a truly exceptional article, I picked up a Fuji XT5 in the spring with a kit lens, after my X has more or less given up on me. When I have time and resource I’ll send it to David Slater to get fixed.

However like you seem to have discovered, jpeg recipes can be addictive once you get under the skin of it. But the Acros with Red filter produces some amazing results. I initially would shoot a scene in Velvia, and then Acros until I discovered shoot once, and then just reprocess it in camera, one RAW and two JPEGs much less space.

I spent an amazing week in North Yorkshire – where else – and never once got my tripod or Df out. I managed everything from seascapes to street shots from handheld.

The difference between the Df images and the XT5 despite sensor difference are negligible, and yes that is accepting resolution too.

Buying a Fuji was one of the harder camera decisions I have ever made, I had a lot of reservations, but someone it won me over quickly – although I’ve found challenges processing RAF RAW files. But that’s resolved for me and I have a decent solution now.

Also I initially intended to buy a GFX until I tested some raw files on my M1 MacBook Air – and it wheezed a lot, the only thing I’ve done with it in five years. So not up for spending out on the camera a lens and a new MacBook Air – I went to the XT5.

The RF seems to have won over many, I’ve seen Icelandic images and now Norwegian ones. Thank you for the article.

Thanks, Dave. I had a reasonably long love-in with Fuji before I bought my first Leica M digital. I just loved the retro looks of the Fuji cameras of the time. And they’ve stuck to their guns.

The RF has had a lot of stick because of the lens and lack of IBIS, but I’m with Brian Nicol on this — it’s not a deal breaker. The fact is that if you want MF image quality and don’t want to carry a ton, the RF is the only choice.

I really hope they make a success if it. But I’m encouraged that Fuji sticks to its guns and develops organically, unlike other manufacturers who swap from pillar to post at the slightest setback. Mike

Wow! I was going to read this on my iphone and happened to notice the 53 minutes read time. I thought it could not be correct and scrolled rapidly for probably 5 minutes and then decided to read it on my computer where I could also better appreciate the exquisite images.

This camera has been on my radar since introduction. I plan to invest on one.

There are no competent reviews on this camera and discovering your post was the final confirmation I needed.

This post is amazing and must be your magnum opus! It is the most comprehensive and as well competent review I have had the pleasure to read. I am totally sold. I only hope that more accessories will become available to pimp it up such as leather half cases.

I do not mind the absence of image stabilization as I am used to M cameras. The rare instance I need better low light performance I will use my Gitzo monopod – there is proper technique to use one. I carry one for balance hiking and for defence in various situations.

I actually prefer the 4:3 sensor ratio since using Micro Four Thirds.

I love the “one glance” to check essential exposure settings as I enjoyed on the Leica M.

As for f/4 glass, I no longer use glass faster than f/4 for my photography adventures.

I have one enhancement for your article after careful study: at the beginning of the article I believe you overlooked the Ricoh GR IIIx/ HDF which I know you are aware is a 40mm equivalent camera, when you stated “common to all current fixed-lens cameras except for the Leica Q3 43”.

My only issue with the incredible article is the product images do not appear exposed properly to me.

Thanks for an informative and comprehensive review with great images.

Again, you have confirmed my future purchase.

Thank you so much, Brian. It really was a magnum opus for me, and it caused me more stress than anything else I’ve written. But it was worth it in the end, all 10,600 words of it. So it is good to find it appreciated.

You are quite right about the Ricoh and I will add a line.

Strange you should mention the product images since I was rather proud of them! I invested in a light box contraption and, for the first time, thought I’d nailed the difficult task of product photography.

The background is white and, somehow they all came out grey. I can see I will have to up my game. There’s more of the same in a couple of forthcoming articles, so you will just have to wince and bear it! I promise to improve.

Mike

Which do you prefer, black or silver?

Interesting question. My silver version came from my local dealer and was a cancelled order. So I grabbed it while the going was good.

I think it looks great, but I also like the black. I have an all-black X100VI and I also love that. I suppose I have the best of both worlds.

But, from your point of view, it’s a personal thing and I don’t think I’m going to be of much help is choosing!

When you do get if, of whatever hue, please let me know your initial reactions. Mike

Dear Mike, I was very interested to read your review; long or short, it chimed with my own thoughts about why Fujifilm were smart to leave out stabilization and to go for a slightly slower aperture lens in order to provide a compact yet super high resolution camera. I love my black GFX100RF, having used it extensively since picking it up in London in April. Talking of which, it must have been you who came into the shop when I collected mine: your mention above of taking up a cancelled order for a silver RF was the jolt that brought back the recollection.

I agree with you that the on/off switch is too easily moved, that the crop control lever’s positioning has led me to turn off the camera when aiming to zoom out, and that the focus stick is a bit mushy and non-responsive; however, as you say, nothing is perfect and to make up for it the EVF screen is superb. I always think the viewfinder is one of the most important features influencing my choice of camera and this one is so good that it actively encourages me to use the crop and aspect ratio options, whereas with an X100-series if I do crop or alter aspect ratio I do it in Photo Mechanic when choosing the ‘keepers’.

By the way, as you may well have discovered, you CAN see the battery charge percentage on the GF100RF: when in shooting mode, not playback mode. simply press the DISP/BACK button to cycle through the viewfinder screens and in one of them the charge percentage remaining shows up in the top right corner. The same applies to the X100VI which incidentally I like so much that — shameless conspicuous consumption warning — I have a silver and a black!

Reading your comments about the reversed direction of the aperture ring settings compared with Leica, I suppose that many other old-school Leica shooters will have encountered this over the years, swapping from M cameras to Nikons when needing to use a longer lens.

Thank you for your excellent review. Thomas

Dear Thomas

Many thanks for your supportive comments. I’m grateful for the tip on battery percentage. I will try accessing that. I am currently in China and have been using the X100VI constantly. I decided not to bring the RF in weight grounds and, by and large, I have been happy. I also have the two lens converters, but I now believe the RF is a better all-rounder because of the wider field of view and the greater crop-ability

Mike

Excellent review Mike. Congratulations! I hope the GFX100RF will be a success for Fuji and I am sure they will continue to refine it and make it even better. If I didn’t already have a Hasselblad X2D I would probably be rather tempted by this camera. Compared to the Hasselblad I would miss IBIS, 1TB of internal memory and obviously the ability to use multiple lenses on the Fuji. The weight and the price of the Fuji is just right though. I love the 65:24 XPan crop mode on the X2D. It is very addictive and it is good to hear that it is also present on the Fuji. About the Sony RX1R, are you sure it was not successful? The Sony RX1R II still sells for over $2K and it is a 10-year-old camera. It pretty much achieved cult status.

Thanks, SlowDriver, a labour of love it was, too. I’ve also looked at the Hasselblad, particularly after Keith James was able to borrow one and tested it recently. But the weight is a big disincentive for me. That’s why the RF appealed.

As for the RX1R, I might be doing it a disservice, because my comments were based on the fact that I have seen or read much about it, nor have I seen any in the wild. In contrast, you see Leica Qs everywhere. Perhaps it’s just that I don’t move in Sony circles. I actually owned one of the first generation and really liked it, apart from the lack of built-in viewfinder. But it is definitely the smallest full-frame fixed-lens camera out there, and I wish it success. I’d borrow one and review it if only I didn’t want to go down the Sony route.

Great review, thanks Mike. Looks like you really had to slum it on the accommodation front too.

I am quite interested in larger sensor cameras and feel tempted to enter the fray. But if I did I would want the flexibility of lens choice to fully exploit such a sensor’s capabilities. It seems like this camera cripples itself with that lens though I appreciate why they made that choice.

For everyday photography, the X100VI would give you everything you need I think. The Q3’s wider lens makes it a more flexible option. I reckon Fuji have filled a niche that very very few people will be interested in with this one.

Hi Andrew, thanks for the kind comments on the review.

Like you, I have been interested in trying MF for some time, and I would certainly be interested in an ILC set up rather than fixed lens. However, weight has always been a disincentive. I’d like to check out the GFX100 II if Fuji will lend me one, but the body alone weighs over 1 KG… then there’s the lens(es).

I therefore saw the RF as the only MF camera that I could conceivably be able to carry around and it didn’t disappoint. I accept the lens compromises, although the lack of stabilisation didn’t really worry me. If you are box ticking, then its absence can be seen as a significant failing. However, if you accept the camera for what it is, it’s just a matter of adapting.

That said, I understand your overall reservations on the aperture and stabilisation and it remains to be seen whether Fujifilm will make a success of this. I hope they do, because I can image the RF II tackling the negative aspects. If Fujifilm demonstrates the staying power they have done with the X100, it will eventually come right.

Strange you should mention the X100VI, which I also have at my disposal. I plan to take it (together with the 28mm and 50mm conversion lenses) on a forthcoming trip to China. I might even put finger to keypad when I return. I was tempted to do an RF reprise, but thought it would be interesting (as you imply) to compare it with the X100VI.

In reference to accommodation, I’m taking my tent to Chongqing.

Thanks for your interest and valid comments.

Mike

It would be very interesting to see the same shots taken with the X100VI and the RF if you could bear taking both with you.

Ah… that’s too much to ask! However, having been trying out Leica Looks today, I’m dithering on whether to take the Q3 43 instead of the X100VI. If I’d still had the Q3, that would have been my natural choice, but I feared that the 43mm lens of the ’43 would be too long for general work in a crowded city. I suppose, though, I would still have a wide-angle view through the Panasonic S5II. Perhaps readers will vote: Which camera should Mike take to China…

That said, you’ve given me an idea for some test shots and I will find a suitable location. There’s always Chinatown…

How about the 20-60mm to go with the Panasonic S5II. Great travel lens. I recently took that and a Q3 43 to Switzerland. The Q3 43 was great for low light, portraits and when I wanted shallower depth of field. The 20-60mm is great for cityscapes, interiors etc.

I suppose I will be one of the very few people. I think this is brilliant. I sold my Hasselblad X1D because the kit was too heavy but the images took my breath away. I am now prepared to make this my only camera: architecture, landscapes, street, travel photography.

Mike, Wow! Ditto on all the kudos for this well done comprehensive review!

I also appreciate all the photos. I am really drawn to the St John’s Wood station black and white image. And who can’t love that rolling shutter shot of the Napier-Railton?

A couple stores called me when they got in the first shipments of the GFX100RF and I turned them down. Not that I wouldn’t love to own one or wouldn’t appreciate it. But I felt it would be a bit of a sideways move from my Q3. I think if I had the Q3-43 and having read this, I can see the merits of having both.

Thanks for the fabulous review.

Dear Joel,

Good to hear from you. I’ve heard positive things about you from my colleague Keith James and, of course, seen evidence of your excellent work. So your comments on the RF test carry that much more weight.

You are right on the Q3 v Q3 43 question. When I bought the ’43 I decided to sell my Q3 because I suspected I wouldn’t need it. While the ’43 is a wonderful camera and, in many ways, superior to the Q3, I soon found that I missed the full-frame 28/35mm experience (I have an X100VI and Ricoh GRIII, by the way). The RF sort of fell into my lap. On the one hand, it gave me back a high-performance 28mm-equivalent angle of view, but it also satisfied my curiosity about MF. I’d always avoided the larger format because of the weight.

So, I am grateful to the RF for giving me back my 28mm and a monster sensor that makes cropping so viable. It has its faults, and I’m already looking forward to the RF S or RF II (or whatever suffix they decide on) and I wish Fuji well. I don’t worry too much about criticism from Leica owners who, naturally, can make a strong case for the Q3, because there is a whole market out there. And the enormous body of X100 owners are fruitful ground for MF-ification.

Incidentally, I also love the St. John’s Wood image, largely because of the wonderful design and those magnificent uplighters. It must have seemed so futuristic when the newly-constructed station was opened in 1939. I almost didn’t include it because it’s not exactly spot on from a technical point of view, but the overall impression is evocative of the pre-war age.

Mike

Hi Mike,

I’m happy to know Keith has said positive things. 🙂 I feared I might be driving him a little nuts with changes/edits to my current article. He is so great to work with and although I am only at one and a half articles contirbuted to Macfilos so far, I have thoroughly enjoyed working with y’all.

I didn’t realize St. John’s Wood station opened in 1939. In your black and white image, it has a timeless feel and peronally not knowing that station, I could believe it is a new one with a retro look. Again, nicely done!

I suspect I will have a serious look at the next iteration of the RF. For the time being I am quite happy with my Q3. I have long been intrigued by the Q line but never considered it previous to the Q3. I didn’t want a 28 as an only lens and I need the resolution to make large prints. Of course the Q3 added many other nice features but at 60MP I can still get sufficient resolution at 35 and 50mm crops. Also I surprised myself at how much more I use the 28mm than I expected.

Cheers,

Joel

Great work, Mike. You mentioned this to me earlier in the week. The output from the camera looks great, as its does from most digital cameras these days. The thing that always stands out with Fuji are the colours which are derived from its film past. Personally, I would ‘take down’ the Velvia look images a bit, but that is down to taste. The red occasionally hurts the eyes a bit. I find that Lightroom can do most adjustments quite well from RAWS, but you have to be careful when adding ‘Nik’ filters such as Color Efex. The best filter in the Fuji system, in my experience, is ACROS + red filter which can really add punch to an otherwise dreary black and white scene.

As with the Q3 , the ‘zoom’ feature is just cropping, but the RF has more MP to ‘throw away’.

I hope that the camera is a success. We will probably only know if and when Fujifilm adds another iteration.

William

Thank you, William. I agree with you on both counts — the slightly over-saturated appearance of Velvia and the excellence of Acros +Re. As you say, though, it is a matter of taste. Having decided to make film simulations a key part of the test (every story needs a theme), I realised that fiddling with the settings to reflect my personal taste was not a good idea.

I was impressed by the way in which all 20 simulations are integrated into the RAW processing (in Lightroom, at least). Even if you shoot only RAW, you can apply any simulation as a starting point. I discovered this only halfway through the test. I found it very useful, for instance, in creating 20 different versions of the little tug boat picture. Instead of taking 20 pictures, I just used one RAF file and saved a copy for every simulation.

I dismiss the cries of “no stabilisation” or “slow lens”. Fujifilm, of all manufacturers, responds to criticism and has a history of staying power — organically developing a camera over many years (vid. X100). Criticisms will be addressed one by one until the RF is a genuine contender. With future sensor price reductions, the RF could well become the go-to MF camera for those who don’t want the weight of a full system.

Thanks again for the points you make. Mike

Well

I think that Very Extremely Comprehensive is certainly the expression to describe your mammoth article – well done! (How many words is it?)

I think you’ve done a fantastic job describing the camera and the features, and whilst it does have a ‘medium format’ sensor the difference between a 36mm sensor and a 44mm one (the difference between a 36” print and a 44” one) really isn’t very much – looking at MP (ie area) I feel is misleading – and calling it medium format doubly so (which should be 60mm by 40 – much bigger!)

On the other hand I can see that it’s a great lens and a great sensor (probably substantially the same as the Q3 SL3 M11 Sony A7r V etc. etc. )

You’ve done well to concentrate on the in camera processing options.

Me, I’m not so fussed about the missing image stabilisation or the rolling shutter – what would make it a complete no-go for me is two things:

Proprietary RAW format – after my last Fuji raw files kept changing with different iterations of Lightroom

No weather sealing, not just because of rain, but I would also worry about dust getting in

I think Fuji’s film modes are really clever – and Leica are coming along with their ‘Looks’ – and I can see that they are really popular but I think all this stuff is best done in Lightroom!

Still – I’m glad you’re enjoying it – and I’m sure that lots of people will find your review really helpful. Your enthusiasm is positively infectious, so I think it just lodges me in the ‘grumpy old man’ category!

Great pictures too – and it looks like you’ve been having a fun time which must be good!

All the best

Thank you, Jono. First, please accept my thanks for all the support you’ve given during the gestation period of this long article (despite your misgivings about the camera). You’ve clarified some of the more esoteric aspects of sensor design and other issues, and you have been patient and so very helpful.

We have discussed these aspects privately but, for the benefit of readers, I did incorporate your reservations about the various MF formats, and made it clear that the Hasselblad/Fuji size is small compared with traditional medium-format dimensions. All we can say with certainty is that it is bigger than full-frame.

I now understand your concerns about proprietary RAW files; it’s something I hadn’t considered and should have mentioned. I haven’t had any difficulties, but I can understand the potential issues. Our friends at Panasonic also have a proprietary file, I think, so Fuji is in good company. It would be good to have one standard.

Agree with you on the stabilisation issue. I approached this camera in the same way that I would handle the M11… just make sensible choices and compensate with a bit of extra speed. The lack of weather sealing on the lens is a problem, of course, but it is no different to the X100VI or, in another instance, the Ricoh GRIII in this respect. I’d always add the 11mm adapter to the RF and a filter to protect the lens, even if I could get away without the hood.

Anyway, thanks for your input and unfailing support.

Best wishes,

Mike

Sorry, I forgot. It is 10,600 words and, according to Mr AI, has a reading time of 56 minutes. Good luck to you all, and I hope it’s worth it. It took me more like 56 days from start to finish… and I’ve nagged the life out of my long-suffering colleagues.