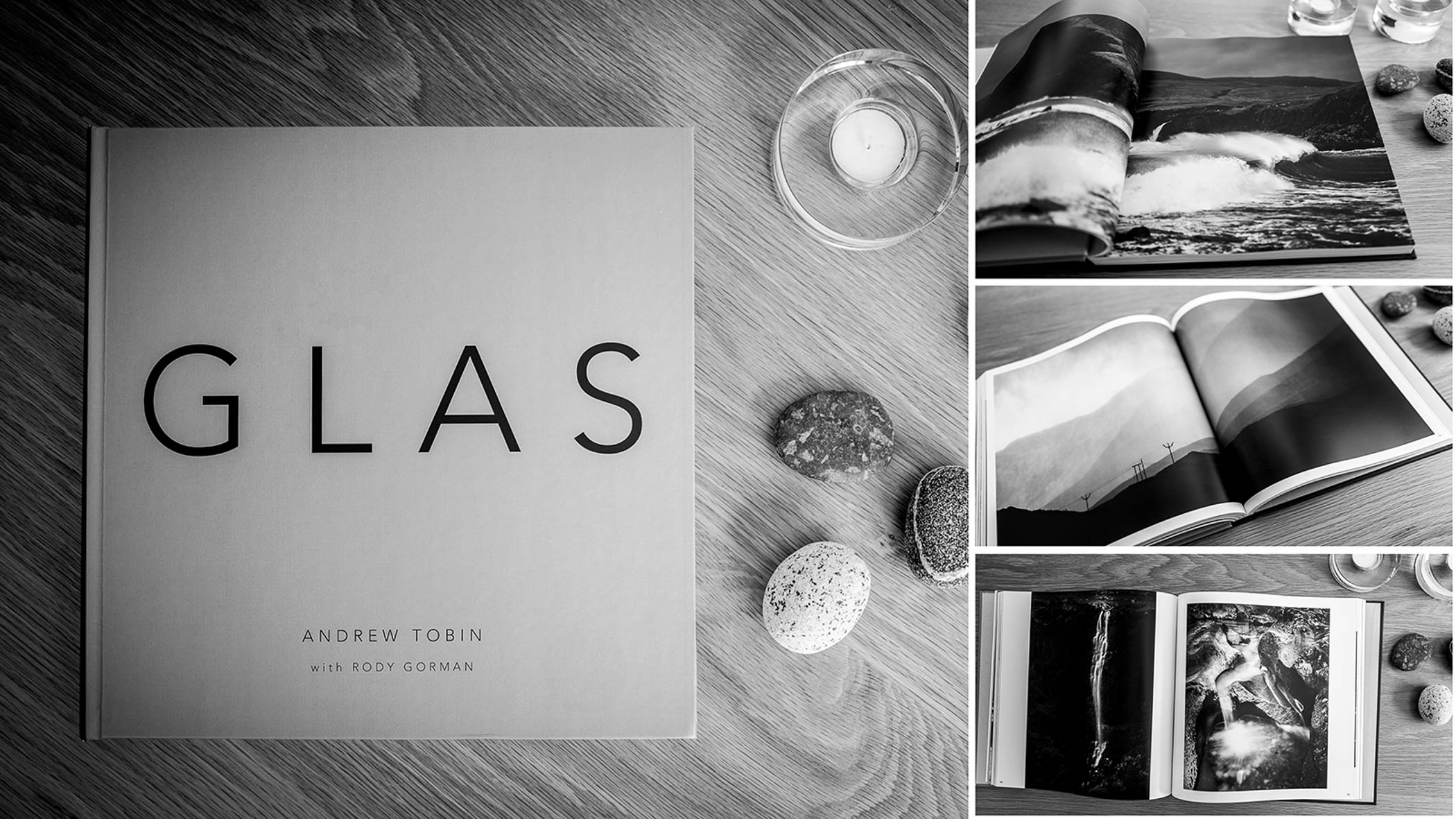

In the previous article, “An exclusive Macfilos preview of Glas — a seminal work on the Isle of Skye” I described my philosophy and motivations behind the creation of my new fine art book, Glas (which means “grey” in Scottish Gaelic, although it does seem to have more than a hint of green in the mix over in Ireland). In this second part, I will describe some of my background, how I went about the photography for Glas, the importance of projects for stimulating creativity, and the trials and tribulations along the way.

Glas has been part of my photography life for seventeen years. It has been instrumental in shaping my approach to photography, and responsible for pushing myself into new territory. Glas has become an instrument to enable self learning and to explore how to create compelling photographs that form a complete body of work.

Nothing else in my decades of photography has had such a profoundly positive impact on the joy and fulfilment I get from photography, and I hope that I can share some of this with you so that you might enjoy similar benefits.

The need to be loved

Like many of you, I have photographed all sorts of things in many places. I have some individually lovely images, and a huge amount of dross.

And then comes the question: what to do with all these images?

For one reason or another, I decided that winning camera club competitions would help, so I joined a camera club. Over a couple of years, I realised how rubbish my photography was, and had a dawning realisation about the incredible depths of photography itself — the different styles, subjects, meanings, and approaches. I didn’t win anything, either.

My desire to win competitions, I realised, was part of a need for recognition. It was important for people to see my photographs and appreciate them. So began a decade-long quest to climb the slippery ladder of sports photography, as I figured that the way to get plenty of people to see my photographs was to have them published in national newspapers.

This worked. It culminated in my photographing the FIFA World Cup in Brazil in 2014 as well as Premier League football, international rugby and scores of other sports. I was published on the front and back pages of newspapers across the UK and internationally. And I got to be in the best seat in the house at major sporting events. What’s not to love?

Listening to the quiet voice within

While all this had been happening and, frankly, taking over my photography life a bit too much, I found I was appreciating the quieter moments when I got to escape for a bit of landscape photography. I enjoyed exploring around the southeast of England, travelling to the coast, finding ruined castles and photographing urban landscapes.

Once a year, I would migrate to the hallowed ground of Northwest Scotland for a precious week of photography indulgence.

After a while doing that in my spare time, I found I was creating temporary enjoyment, rather than longer-lasting satisfaction. Again, I was just scratching the surface of this photography lark.

The power of a project

It was practically too difficult to keep travelling farther and farther afield just to have thirty minutes at dawn at a nice location, fun though it was, so I started looking closer to home.

As I did so, I realised that it wasn’t necessary to travel to some well-known photogenic location to get satisfaction. True creativity only started to enter my photography life when I started my first “proper” project. I could stop chasing “trophy shots” and concentrate on something deeper. So how did I go about it?

Near my house at the time was a piece of heathland — sort of grassy scrub with some heather and random trees — which was very unattractive from a traditional photography perspective. Called Whitmoor Common, it is flat, featureless, and irredeemably dull. It presented a challenge. But it was nearby so I could get there in five minutes.

I started visiting regularly. To make matters even less conventional, I decided to use one camera and one lens, my Sony A7R and a manual focus Canon FD 85mm f/1.2. Definitely not a traditional landscape lens. Over time, with this strange equipment and featureless terrain, I had the most enjoyment with my camera I could recollect.

Finding new focus

This project gave me an excuse to try different approaches. It gave me “permission” that I didn’t know I needed. I felt my brain becoming more open to new ideas. I found my images were reflecting more than just a digital record of a scene. They were starting to transmit mood and emotion. This opened my eyes and it stands out in my mind as a transitional period from “person with a camera” to “photographer”.

The focus of having a project helped tremendously with the creation of Glas, and my other book Skye At Night. Both have been multi-year projects, with Glas being seventeen years and Skye At Night running in parallel to Glas for five years.

The idea for Glas began in 2008 when, during a visit to Skye, I photographed Castle Moil lit by gorgeous fleeting light just after a storm. Converted to black and white, it looked epic and conveyed mood and drama in a way that just worked. I didn’t know it back then, but I had inadvertently started a mega-project that I adjusted and expanded over the years to come. I guided it and it guided me.

Recommendation #1: Have a project. But it doesn’t need to be a seventeen year one.

Evolution, change, adaptation

A project like Glas is like a living, evolving entity. Glas changed over time. It wasn’t called Glas until it was fifteen years old. It wasn’t even a book to start with. I had in mind a nice selection of black and white images for a gallery on my website.

Falling deeper into the rabbit-hole that I had dug for myself and drawing on my experience from my Whitmoor Common project, I started to visit Skye regularly and looked for ways to express how the island “felt” to me.

Translating three dimensions and all the other senses of smell, sound, taste, hearing as well as “character” into a two-dimensional photograph is the challenge. How could a photograph, devoid of everything apart from the sense of sight, convey so much more?

Removing colour was a conscious decision. By removing colour it leaves space for the viewer to fill in the blanks. Photographing in bad weather was another. Not for me the nuclear sunset or startling dawn. Conveying mood and feeling means creating a visceral impact in the view so they can imagine what it must be like being there. I found horrendous weather to be my friend.

Digging beneath the cliché

I also wanted my photographs to get across the character and quirks of the Isle of Skye. The island is a lot more than the usual world-famous tourist hotspots of the Fairy Pools, Old Man of Storr and Neist Point. Sure, they are great locations for photography, but they miss many of the nuances and delights that are on offer on Skye.

Like all the Scottish islands, Skye has its particular atmosphere and ambience. I decided to seek some of the more intriguing aspects of island life that give the place its unique flavour. Gradually, over many visits to the island, a “body of work” began to evolve which was just starting to get across what I wanted. But it was rather messy and needed to be curated in some way such that it would make sense.

Themes to the rescue

At about 3 am one winter night, an idea reared its head and shouted at me, “you need to split it into different themes, you idiot!”. Doh! Divide and conquer. Of course. I could take the behemoth that I’d been worrying about and chunk it up into easily manageable pieces, and then focus on each of them individually. A set of “mini projects” if you like.

The next morning, I started organising the images I already had into some logical themes. I had quite a few weather-related pictures, so a “Weather” chapter was an obvious first decision. I had also been photographing some of the little white cottages that are tucked into the astonishing island landscape, resulting in a “Small Houses” theme. Then, there were plenty of coastal shots, so “Sea Views” was born, followed quickly by “Water Features” for the rivers, waterfalls and lochs that I had captured.

The impact of themes

Later that day, I had a list of ten themes, which eventually became twelve (see my previous Glas article for the list of themes). This was, quite literally, a revelation. It is something I really should have thought about earlier, but didn’t.

The impact of having these themes was threefold:

- It gave me focus. I would decide: “today I am photographing fences (one of the themes)” and go out looking for interesting fences. Rather than roaming the landscape randomly, I had purpose each time I went out.

- It gave me permission. I don’t know why I needed permission, especially from myself, but now I did. I had an “excuse”.

- It gave me structure. Rather than having many random though lovely images, I now had a framework to put everything into. I can’t explain how important this was to me.

Recommendation #2: If it feels too big, split your project into manageable pieces.

Just not good enough

I started getting very excited about what I was putting together. I made a sample 70-page hard cover photobook to see how it looked, how it flowed, and most importantly to seek feedback from those close to me. To do this I used Lightroom’s Book module. I thought it looked bloody brilliant, and I couldn’t wait to show it off to my long-standing photography friends in the local pub.

I knew I was in trouble when one of them said “it feels like there is a lot of filler”. Uh-oh. I paused and went and got another round of beer for everyone. Then I asked “roughly what proportion of good stuff to filler”. “About 20:80” was the reply.

Earth shattering. But they were right, and I had been blinkered by my own enthusiasm. It wasn’t good enough. I had to make it better.

Recommendation #3: Seek the feedback and guidance of others.

No more messing about

I returned to Skye with a mission: to create simply the best possible body of work about Skye ever. I studied the work of many of the photographers that I admire, like Rene Burri, Sebastiao Salgado, Bruce Percy, Minor White, Steve Curry, David Ward, Ian Lawson. And then critically analysing the work I had already produced. Lists of my own compositions were developed to reshoot. And most of all, deciding not to settle for anything less than awesome.

Shape, contrast, and simplicity became the drivers of what followed.

I returned to some scenes ten or more times to get them right. Horrendous weather, freezing cold and horizontal rain did not stand in my way. I wanted to make each image the best it could possibly be without compromises.

Wanting to change perspective

The shot below is a good example. The well-known Allt Dearg Cottage near Sligachan is usually photographed from a lot closer to show the river flowing past. But I wanted to get across a sense of isolation and loneliness, so eventually found a different composition well away from any paths. It then needed snow on the mountains and the right moody sky to go with it.

I also spent a lot of time exploring harder-to-reach spots to create original compositions that fitted the brief I had given myself. This was extremely rewarding. Putting in the extra effort to find somewhere fascinating and then spending time slowly considering different compositions before setting up and triggering the shutter is very fulfilling.

Discovering something different

By kind coincidence, I made some of my favourite photographs while shooting something entirely different. The shot below, for example, best viewed large, shows a tiny white house at the extreme left of the streak of sunlit ground on the far shore. I had been waiting for an otter for what seemed like hours (it was hours actually) and bided my time watching the play of light on the mountains in the distance.

Eventually, a sunbeam-of-photographer-happiness aligned with the small-house-of-much-joy and all that was left to do was press the shutter. I also got the otter shot, which is in Part 1 of this article.

The extra effort I was putting in was yielding rewards. I felt my photography was improving significantly the more I tried and the harder I worked. What I discovered was that I could set my own standards far higher and achieve those higher standards by putting a lot more into my work.

Recommendation #4: Try harder.

Editing and printing

To finish this second part, I’ll describe some of the processes after the photographs have been made that led to the creation of the final result, a proper high-quality book.

I have used Lightroom for almost all my editing work since v1 many years ago, and it is now a natural extension of my photography process. Over the years I have built up a rapport with it and, much as I despise Adobe’s horrible subscription model, it is an incredible piece of software.

I created a couple of black-and-white presets that had the look I wanted, and I would apply these as I was importing images from my memory cards. This gave me immediate feedback from a composition, shape, and contrast perspective.

For those images that made the initial pick/reject cut, I’d spend quite a lot more time on each of them. Occasionally, I would venture into Photoshop, for example when I merged two images, such as a short and long exposure used in the image below.

Adding new tools to do the job properly

I had to drop some more subscription money on Adobe InDesign. I quickly reached the limits of Lightroom’s Book module. It couldn’t handle the number of pages I wanted, and it kept screwing up the formatting as well as losing track of page numbers. It became increasingly annoying, so I splurged to do it “properly” with InDesign.

I have worked hard to get a consistent look to all the images in Glas and ensure there is a good variety of layouts but not too many, so it gets messy. I decided not to have any captions in the book as I felt that they broke up the flow and clean, minimalist design.

This meant creating a separate book that I have called the “Photography Index” which contains all the technical information about each image along with location information and little stories or anecdotes about how they were created.

How to pay for the very best quality

To manage pre-orders I have been running a Kickstarter campaign that has already met its target. That’s great progress and well ahead of my expectations. I will now be able to pay for the substantial printing costs. I will now be able to pay for the substantial printing costs. There is still plenty of room for more Kickstarter backers who will get Glas at £140 instead of the £170 retail price. So it is worth putting in a pledge on Kickstarter, as Kickstarter backers not only get a lower price but also priority, getting their orders before anyone else.

Printing is the next stage. As I am printing two books (Glas itself and the accompanying Photography Index), and a slipcase, with high-end materials it isn’t cheap. It also turns out that printing black and white with no colour cast is really difficult and needs particular care and attention. I have interviewed several printing companies and am pretty settled on the one I want to use and I am currently working on with my selected printing company on how I want to print it.

Choosing the right printing option

Digital options are ink-jet, toner and digital offset. The “analogue” option is litho. Litho should give the best quality, but because physical plates have to be produced that fit onto drums in the printing press, the setup costs are very expensive for a short print runs.

Digital offset can rival litho for quality, and involves an image being digitally but temporarily imprinted into a roller to pick up the ink, so there is no need for physical plates to be produced so setup costs are cheaper. Both litho and digital offset create very consistent results which can’t be matched by ink-jet and toner printing.

The choice is therefore between litho and digital offset. To make this decision, there is a lot of to-ing and fro-ing with sample prints, different settings for PDF files, line screen settings, ink densities, ink spread factors, paper types and so on. It is very time consuming but a necessary evil. The process of preparing test files, getting samples printed, adjusting the settings on InDesign and repeating multiple times is lengthy and painstaking, and not nearly as much fun as the photography itself.

Recommendation #5: Don’t underestimate the amount of time you will be in front of your computer.

Summing up

Firstly, and being completely transparent, I’d be more than delighted if you pre-ordered a copy of Glas using Kickstarter. Judging demand is incredibly difficult, and I’ll likely only ever print around 100 copies, such is the printing cost. This will make Glas a rare and lovely thing.

Secondly, I hope that you have enjoyed this rather monumental journey that I have undertaken. I’m happy to answer any questions in the comments, and even address the whole book creation process in detail in another article. I have learned a huge amount about photography, my own motivations, and how to get the most out of my own capabilities.

Lastly, I encourage you to make the most of this strange hobby/activity/infatuation that we call photography. The personal fulfilment it has given me is considerable, and it has saved my own sanity when the pressures of the day job (cybersecurity stuff) have become intolerable.

When stuck in a rut, having a project is the way out. It doesn’t really matter what it is, but it will get your creative juices flowing. You don’t need to create a crazily complex book as I have, or run the project for seventeen years. Whatever project it is you will find it gives you purpose and direction, and helps to develop your photography hugely.

Cameras and kit

You might find this interesting, if only as a good example of Gear Acquisition Syndrome (GAS)

- 17-year project.

- 22 cameras used, from mobile phones to various Leica M’s and Qs, with some Fujis and Sonys added into the mix, plus the recent arrival of a Ricoh GRIIIx HDF.

- Favourite camera to use: Leica Q3.

- Least favourite camera to use: Sony A7III.

- About 70,000 frames in total

- 3,500 made it through the initial pick/reject cut

- 611 were considered for inclusion in Glas

- 194 made it into the book.

- 0.28% “keeper” rate

Make a donation to help with our running costs

Did you know that Macfilos is run by five photography enthusiasts based in the UK, USA and Europe? We cover all the substantial costs of running the site, and we do not carry advertising because it spoils readers’ enjoyment. Any amount, however small, will be appreciated, and we will write to acknowledge your generosity.

I now have my copy of Glas, and I can confidently say it’s the highest quality of production of any photography book I own. It really is magnificent, and the photos are absolutely first rate too. It fully justifies its not inconsiderable cost. Andrew’s decision to include Gaelic poems by a local helps to create a rhythm as one reads through the book, even if they’re inevitably less effective for someone like me who had to rely on the English translation, they still serve a purpose. The book is a masterpiece, and if there any copies left and you’re tempted to buy – don’t hesitate.

Andy, it’s fascinating to read your progress with the book – and good to hear you’ve hit the target and it will happen! Personally, I don’t see what’s so terrible about Adobe’s subscription model (which I see Topaz are moving to as well). Photography isn’t cheap, and being guaranteed a fully up-to-date version of Lightroom Classic seems to be something worth paying for – particularly when you take into account how much it’s improved in the last couple of years.

(At a tangent, I’ve just finished my first ever ‘zine’ back from the printers today. Perhaps, modest though it be compared to what you’re doing, there’s a Macfilos feature I should write.)

Hi Paul – I’m sure we’d like to hear about how you go about creating a zine, and also what defines a zine. I’ve always been curious about this. In other news, I’ve just given the go-ahead to the printing company to start the presses for Glas!