One hundred years ago a unique typeface, the Doves Press Type, was lost to the world when it was wilfully destroyed by an old man who had fallen out with his business partner. Between 1913 and 1916 and at the dead of night he carried 12lb loads of lead type from his printing house to Hammersmith Bridge on over 200 occasions. In all he consigned 2,600 pounds of metal to the muddy depths, never to be seen again. Or so he thought.

The old gentleman was Thomas Cobden-Sanderson who had founded the Doves Press in 1900 with his partner, Sir Emery Walker. They set up shop in a small house in Hammersmith Mall, next door to the famous Dove Tavern, and a few steps away from the London home of William Morris, Kelmscott House. The press produced all its books in a unique typeface, designed in 1899 and known as Doves Type, which existed in only one size, the equivalent of 16pt. Yet during the First World War Cobden-Sanderson pitched the whole lot into the Thames simply to spite his one-time partner.

Salvage

Until late 2014 it had been assumed that we would never again see any of this discarded lead.

But typographer Robert Green, after three years working on his digital facsimile of the Doves Press Type, decided to take matters into his own hands.

Working with a salvage team from the Port of London Authority, Mr Green has just recovered part of the trove from the muddy riverbed around Hammersmith Bridge.

Some of this metal type will be donated to the Emery Walker Trust as a small recompense for Cobden-Sanderson’s vandalism. But recovery of the type has also enabled Mr Green to create a more accurate facsimile and the digital fount has now been republished.

Cobden-Sanderson had fallen out with Walker because he felt he was not getting sufficient working support. It became an acrimonious dispute and the partnership was dissolved in 1909 with the legal proviso that Emery Walker should have access to the Doves Type.

This restriction clearly festered in Cobden-Sanderson’s mind and within four years he had determined that no one, least of all Emery Walker, would ever use the typeface again. In an act of unprecedented vandalism he cast the type, including all the tools and jigs needed to replace it, into the mud of the Thames beneath Hammersmith Bridge.

William Morris

Both Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker had been close to William Morris, the renowned designer who lived nearby. It was Cobden-Sanderson who, in 1887, suggested a committee to be called the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society which in turn gave its name to the A&C movement. In the following year Emery Walker gave a lecture on fine printing to a distinguished audience which included Oscar Wilde and William Morris. Morris was inspired to found the Kelmscott Press which subsequently depended heavily on Emery Walker’s experience and knowledge of printing.

After Morris died in 1896 Cobden-Sanderson encouraged Walker to go into partnership to establish a private press of their own. Funding was provided by Anne Cobden-Sanderson but, crucially, it was agreed that Emery Walker could take for his own use a fount of the type they intended to design, something that never happened.

Digital renaissance

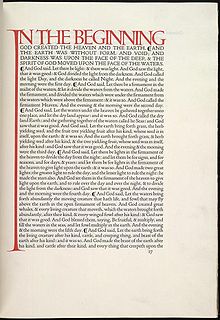

Initially this was an idyllic partnership. Between 1902 and 1905 work was concentrated on a five-volume English Bible (see facsimile above) which is thought to be the firm’s masterpiece. The opening of Genesis is now considered to be one of the world’s finest printed pages.

Over a year ago the Doves Type did make a reappearance, not from the bottom of the Thames but on an iPhone near you. The typeface was meticulously salvaged in digital format by designer Robert Green and can be purchased for as little as £40. Cobden-Sanderson would probably have approved of this new arts and crafts movement in typeface design. It is booming, thanks to digital compilation, with none of the disadvantages and costs that go with producing traditional lead type.

Typefaces are now safe from vandalism and no one can again spite the world by tipping a load of lead over Hammersmith Bridge.

I wrote originally about the Doves Type in January 2014 and the news of the recovery of some of the type has prompted me to rewrite this article. The accompanying photographs (except for the salvage shots and the Cobden-Sanderson house) were taken with a Sony A7r and Leica 35mm Summilux-M FLE. Cobden-Sanderson house taken with Leica M-P and 50mm Apo-Summicron ASPH.

Fascinating and very well told.Like reading a story in the New Yorker and such a contrast to the perfunctory content of most blogs.More please.

Thanks, John, much appreciated.