This indeed could be a Pythonesque review: The Department of Silly Comparisons, Mirrorless Camera Division. Who on earth would compare a Leica SL with a Fuji X-Pro2 and (wait for it) an Olympus OM-D E-M1 with its four-thirds sensor? Madness, I hear you squeak.

Not quite so, however. These cameras may be completely different in size, price and just about everything else. But with their respective pro zoom offerings they are all attempting to satisfy a common demand: A craving for a high-quality weather-resistant camera attached to one lens (also weather resistant) that does most, if not all, you could want; a lens that to all intents and purposes can replace all but the fastest of primes at all common focal lengths.

Click on images below to see full comparisons

Expectations

I have been looking at these three cameras together with three outstanding lenses. At the outset, however, I need to make it clear that this is not an in-depth assessment of the optical qualities of the lenses, nor the detailed operation of the cameras. It is more an overview of what you can expect from a pro outfit—in terms of weight, handling, price and facilities—depending on the size of sensor you choose. It is a sort of starter pack to sift out your choices.

Generally speaking, the bigger the sensor, the bigger everything that goes with it. I have provided some images to compare although most were done very quickly because of the circumstances. They are merely examples and not precise comparisons. All shots were taken with the cameras hand held.

The lenses in question are the Leica 24-90 Vario-Elmarit f/2.8-4, the Fujinon 16-55 f/2.8 and the Olympus M Zuiko f/2.8 12-40. How are they similar? In more ways than you might think. All attack the same range of focal lengths, everything from a full-frame equivalent of 24mm right through to 80 or 90mm. The Olympus tops out at 80mm while the Fuji adds a few extra millimetres to reach 82.5. The Leica goes the whole nine yards to tickle the traditional staple focal length of 90mm.

For 99 percent of my photography, this is the range I work in. But I see the starting aperture of 24mm as important; it is an essential component of a do-it-all lens in a world where most lesser zooms start at 28mm. Yet those extra four millimetres make a huge difference to design difficulties and production costs and help explain both the size and weight of these lenses.

All three lenses are weather sealed (as are the cameras), all have fast apertures that are more directly comparable than the bare figures would suggest, and all are the finest and most professional zooms the respective manufacturers can aspire to. All have great performance and are capable of replacing primes at every intermediate focal length.

Aperture range

Two of the lenses, the Fujinon and the Olympus, have a fixed aperture of f/2.8 throughout the range while the Leica offers f/2.8 to f/4. In reality, though, the Leica is the fastest of the bunch and will provide the narrowest depth of field, thus the greatest opportunity for subject isolation. On the APS-C Fuji, f/2.8 is equivalent to f/4 in full frame terms while f/2.8 on the Olympus is similar to f/5.6 on full frame, particularly in terms of ability to isolate subjects. This article discusses the differences between a given aperture in conjunction with various sensor sizes.

In terms of cost, weight and size, all three of these lenses are predicated on the sensor size, from the Leica’s full-frame, through the Fuji’s APS-C to the Olympus with its relatively small micro four-thirds chip which is one quarter the size of the full-frame. Since all three lenses are professional in design, build and optical aspiration, none of them is what you would call light. In fact it is the two Japanese zooms that shock in relation to their manufacturers’ lightweight prime offerings. The Leica zoom weighs 1140g, the Fujinon 655g and the Olympus a slight 382g (which is nevertheless heavy for an MFT lens).

Compare these three camera combos on cost and the cheapest, as you would expect, is the Olympus OM-D EM-1 and zoom at around £1,350 (as a kit) followed by the Fuji at around £2,000 and the Leica at around £8,500. Significantly, none of these combos is what you would call cheap. That’s because they are all up to pro standards.

In combined weight of camera and lens the Olympus is again lowest, at 870g but followed closely by the Fuji rig at 1150g. In the heavyweight corner is Leica’s bruiser, the SL, at a relatively whopping 1987g.

Sensor size

All this is more or less what you would expect when you take into account sensor size. The Leica body is actually relatively light for what it is (a directly comparable Nikon D5 or Canon’s EOS-ID weigh in at 900g and 805g respectively). With their similarly professional 24-70 pro zooms these camera combos weigh 2300g and 2145g respectively. Such heavyweights put the relatively lithe Leica into context.

The Nikkor lens is even longer than the Leica, even though it has a shorter 24-70mm range. As an aside, the Nikon rig costs around £6,600 and the Canon £6,300, thus again putting the Leica’s £8,500 into perspective. Leica has never been cheap but it isn’t ridiculously overpriced bearing in mind the build and optical quality and the possibility of higher value retention, not to mention the pleasure of ownership.

As far as size goes, you just cannot overcome the laws of physics. If you want professional optical performance you pay the price, in terms of weight and bulk and the hole in your pocket.

All three of these mirrorless camera and lens combinations deliver superb performance. Whichever you go for, the decision has to be based on weight, convenience and, of course, price. Micro four-thirds, for instance, might be the smallest sensor but the results can be exceptional, perhaps as much as most of us really need unless we are hoping to flog our shots to JCDecaux. Indeed, I know of one Leica reviewer and SL fan who always keeps an Olympus (at the moment the new PEN-F) by his side for those times when he doesn’t want to lug around a heavier camera. It’s a good choice. I suspect he reasons that if he is going to do without full-frame goodness he might as well go for lightweight goodness rather than compromising with the in-between Fuji rig. I can well understand this.

Available options

Lucky me, I have had the opportunity to try all this kit and, with the help of Andy Sands and his team at Chiswick Camera Centre, I spent a morning out shooting with the Olympus, Fuji and Leica. This is not by any stretch of the imagination a thorough test of any of these camera-lens combinations. The object is simply to demonstrate the options available in the three most popular sensor sizes.

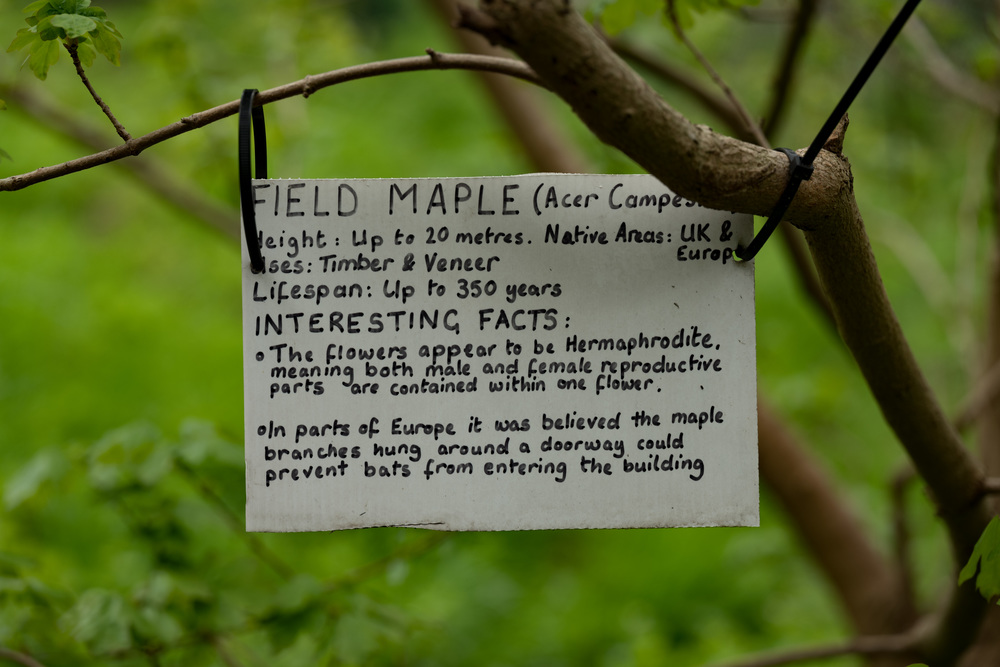

I spent about 45 minutes with each combination, scuttling back and forth from the dealer’s premises at Chiswick Park to the minute but rather endearing Gunnersbury Triangle nature reserve which neatly fills the space between the District Line junction of the Richmond and Ealing Broadway lines. Where possible I have attempted to get equivalent shots for comparison purposes and to illustrate this article.

In terms of handling, the Olympus is the smallest outfit (although the camera body is bulkier than the Fuji and weighs almost as much; it is the Zuiko lens that is smaller than expected) and that made it really handy. With this camera it is possible to enjoy the useful 24-80mm focal range with the minimum fuss. This is a camera you could carry all day without tiring. The 12-40 lens, too, has the best ergonomics of the three with its clutch ring to switch very rapidly between manual and auto focus. On the Fuji it is necessary to fiddle with a small switch on the front of the camera, out of sight and out of mind (however there is the facility, as with most modern Fujinons, manually to override the autofocus while half pressing the shutter button).

The SL is middling convenient, with the front button next to the lens customisable for focus selection (everything is customisable on the SL so you can tune it to your shooting style and choose the purpose of every button to suit your whim). All three optics have admirably damped zoom and focus rings and, unlike with many autofocus lenses, all have a short throw for focus with clear end stops. These are all high-quality constructions.

The SL lens is quite spartan by Leica standards. There are no aperture markings, no distance scale. The only legend shows the focal lengths from 24 to 90. The Fujinon, in contrast, has aperture markings in addition to the zoom range scale. The Olympus lacks aperture markings but does have a convenient focal distance scale which appears when the clutch ring is pulled forward to switch over the manual focus. Of the three, the Zuiko has the best ergonomics and is easiest to use. As fan of Leica manual lenses (and the fixed lenses on the X Vario, X and Q cameras), it sticks in my craw to admit this.

Both the Olympus and the Leica have effective optical stabilisation—in-lens in the case of the Leica and in-body for the Olympus. This is the famed five-axis system which is claimed to be the most effective on the market. The Fuji lacks stabilisation, either in body or lens.

All three zoom lenses protrude as you would expect when zoomed to maximum focal length but none is excessive. The Leica extends by 4.5cm, the Fuji by 3cm and the Olympus by just 2.4cm.

Complex

Of the three cameras, the Olympus is the most complex electronically and the most frustrating to approach for the first time. The menu system is fiendishly complicated and extremely difficult to master without copious reference to the instructions. For instance, I spent the best part of an hour trying to find out how to set RAW instead of JPG. The manual wasn’t much help and eventually I resorted to an Olympus forum thread.

This is obviously a difficult topic because there was a lot to read. I was advised to select the second option from the left in the “Super Control Panel” which is labelled “LF-RAW”. The only trouble is, as I discovered from another thread, that this control panel isn’t enabled by default. It is necessary to go into the menu and select the “Disp/PC” option D from the Custom Menu. None of this is intuitive. It is certainly easy when you know how but I use this instance as an illustration of the time needed to familiarise yourself with the camera. I have no doubt that an owner will soon come to terms with the controls and will grow to like them; but for a butterfly reviewer such as me things are not easy.

Fuji sits in the middle, a very familiar set up for me: It is logical, relatively uncomplicated and easier than the Oly to master. The Leica also takes a bit of getting used to but, ultimately, is simpler than the others. One unusual feature which I soon grew to love is the total absence of descriptions for buttons and dials (only the on/off switch is helpfully marked in order to give you a clue). But the DSLR-like top LCD panel contains all the important information that you would expect to glean from shutter dials, aperture, ISO and suchlike. It is in reality an adapted display from the Leica S medium-format camera. The SL is a very likeable and easy to use camera.

This, however, is not the place to discuss any of this gear in greater detail; I am more concerned with the general comparisons between three cameras and three lenses with pro aspirations and their ability to replace a bagful of 24, 28, 35, 50, 75 and 90mm primes.

I am also not going to pixel peep at this stage. The examples in the article offer some basis for visual comparison and you can make up your own mind. I would certainly welcome any comments. What is clear is that the sensor size has a big bearing on depth of field, with the full-frame Leica providing the best subject isolation. If you appreciate that razor-sharp in-focus moment then the Leica will do a better job. Subjectively, I felt that the Leica provided the best image quality overall (as of course it should do), followed by the Fuji and Olympus. The Fuji’s colour rendition, which tends to be more saturated in general, is not to everyone’s taste.

That said, when it comes to really big enlargements you cannot get away from the physics. The Leica wins, followed by the Fuji with the Olympus trailing. That’s as expected but, for many people, images are never taken to more than iPad or laptop screen size. Some never stray beyond the iPhone. For them, the investment in a full-frame camera and lens could well be unnecessary. In mini format all three cameras and lenses produce impressive stuff.

Little and Large

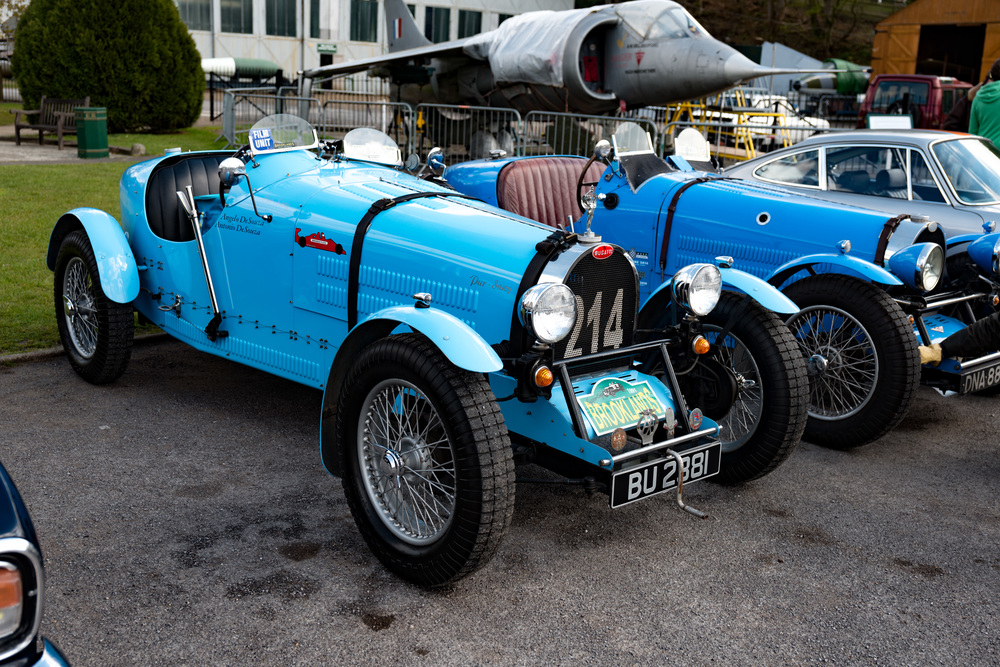

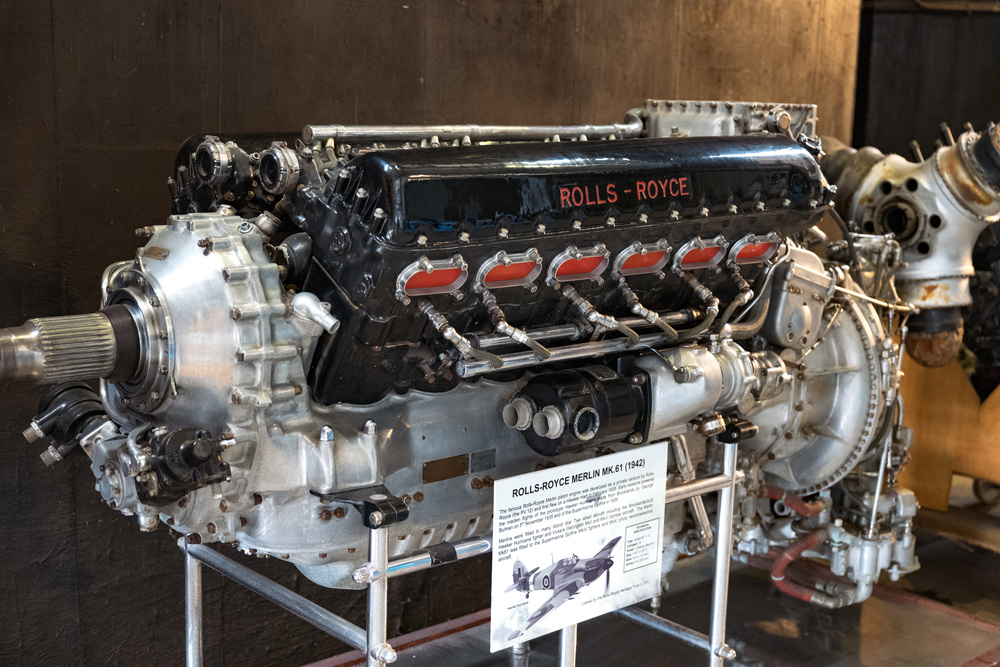

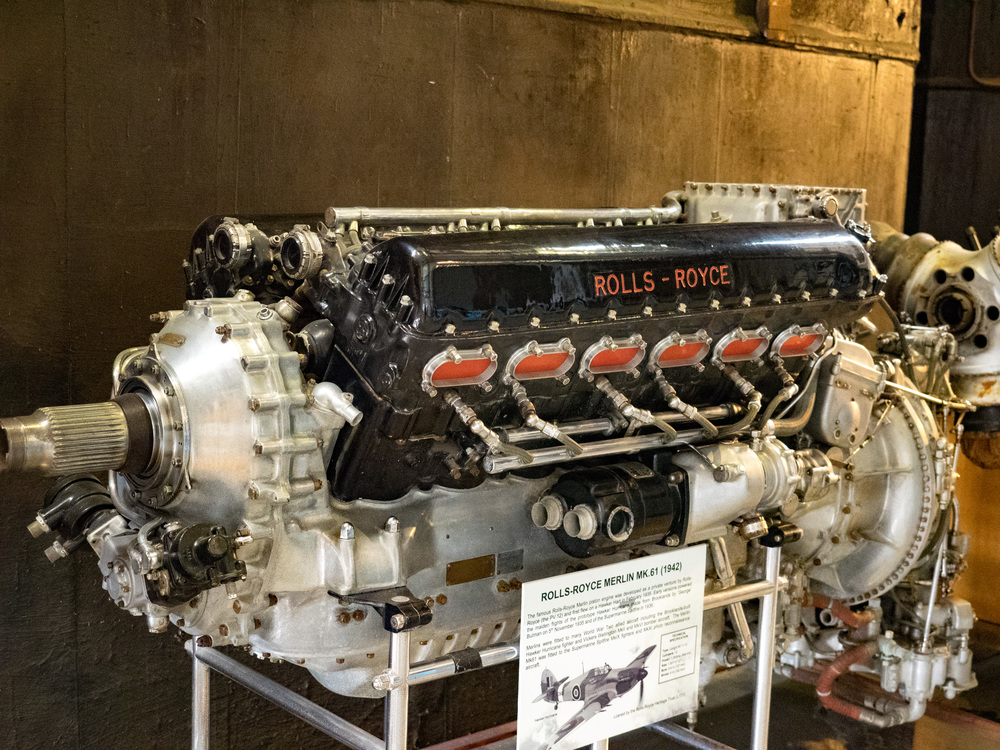

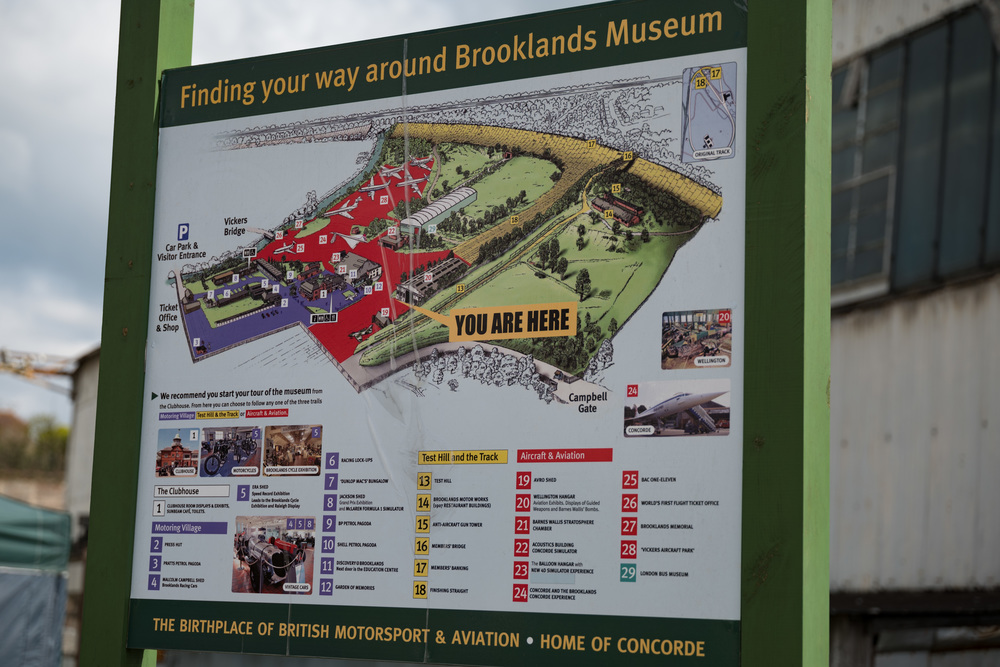

As a sub-test I took Little and Large, the Olympus and the Leica, to Brooklands for some period atmosphere. There is always a good collection of faces and machines to tempt any photographer. I couldn’t manage three cameras and, since the Fujinon 16-55 was back at the camera store, I thought it would be a crafty plan to make a direct comparison between the two extremes. Trust me in that that Fuji lies between the two. I apologise to the Fuji that it wasn’t possible to show a three-way comparison. However, it is interesting to see the smallest and largest cameras side by side.

The smaller Olympus brings the benefit of faster operation. The autofocus on the EM-1, even with the zoom lens, is blindingly fast. I knew this from reading reviews in the past but I was quite unprepared for the reality. The delay between half pressing the shutter and the focus locking is imperceptible. In comparison, the SL is slower. By full-frame mirrorless camera standards it is quick but it does not match the Olympus. The Olympus, too, is the easiest to handle. At under half the weight of the Leica combo, the OM and 12-40 impresses in the hand. It’s a wrist-strap type of camera whereas the SL (at least when equipped with the 24-90mm) is not.

Above all, the Olympus is a camera you would be happy to carry around all day, to pick up and use wherever the fancy takes you. The SL with this zoom lens is the opposite. It is a camera that requires commitment, a dedication to carrying it because you know you are going to get the most detail-filled files which can stand up to massive enlargement. The OM-D is remarkably versatile, packing all those individual focal lengths into one compact lens while not busting the scales. Despite its complex but fully featured control and menu set, I found myself warming to the little beast.

In terms of image perception during shooting, the SL, with its outstanding and enormous viewfinder, provides the firmest confirmation of a job well done. This difference was confirmed after processing. But the Olympus acquits itself extremely well and it is an endearing little camera to use.

Size and weight

It all comes down to size and weight balanced by performance. On this basis the Olympus does a wonderful job and is the camera I could happily travel with and not feel too shortchanged when it came to performance or image quality. The SL, on the other hand, is definitely not a travel camera in my book; I see it more as a special occasion camera (although, with M lenses replacing the massive zoom it becomes comparable in weight with the M240). In this sense the SL is a chameleon–heavyweight bruiser with the zoom, handleable middleweight with M lenses.

The Fuji sits in the middle as was obvious even before I set out. The camera body is no heavier than that of the Olympus (which is something of a surprise and a credit to Fuji) and, if you ignore the heavy zoom and travel with one prime, the Fuji rig will be more than comparable with the Olympus in terms of handling, thus providing a a theoretically more competent option bearing in mind the larger sensor.

Finally, what of the Sony A7 range? Here is a camera that offers a full-frame sensor, excellent image quality and a competing lens in the 24-70 Zeiss Vario-Tessar with its constant f/4. This provides an attractive alternative to the Leica for mirrorless fans and it is hard to gainsay the weight and price advantages (it costs around £3,800 for the A7rII combination, some £4,500 less than the Leica. However, this Zeiss lens, which is slower than the Leica’s, is not rated as highly by reviewers. I have not had the opportunity to try it but it is something you should have a look at if you want a full-frame rig but balk at the German pricing. An altogether better bet for Sony fans is the new G 24-70 lens that really does perform superbly. It’s a pricier job, though, at around £4,400 for the A7rII and lens. That’s still significantly cheaper the Leica, it has to be remembered. And at just over 1500g, the Sony combo is nearly 500g lighter than the Leica.

My friend Kai Elmer Sotto in Singapore is a great Leica M fan (he has just bought the new M-D) but uses a Sony as his go-to bells-and-whistles digital. He finds the SL slightly too big and heavy and feels more comfortable with the Sony. I can understand this.

There are only two full-frame mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras on the market, the Leica SL and the Sony in its various guises. I am biased in favour of the Leica because it is an easier camera to understand and operate. The Sony A7 body is also quite small when seen in the context of these lenses. The bigger Leica is perhaps a tad too big, but it does feel more balanced in my hands.

The difference in price is more than enough to make the Sony a very compelling alternative and I am sure that many users would argue that it has the legs of the SL. So it is excluded from this test not on lack of merit but simply because I didn’t have one to hand. It’s worth a look if you want more than the Fuji or the Olympus can offer but don’t want to shell out the best part of £9,000 on the Leica rig.

Primes vs. zooms

I am not by nature a zoom type of photographer. I prefer a single focal length, probably 50mm is my all-time favourite, and I am a great fan of manual focus. I enjoy the Leica M for its rangefinder and I am equally sold on the SL for its performance with almost all M-mount lenses. But if I am to go for a zoom lens, I need to be sure that it is of an optical quality similar to good primes. I think the Leica 24-90, the Fujinon 16-55 and the Olympus M-Zuiko 12-40 fit that bill. I would be happy to use any of them.

Interestingly, all three of these lenses perform exceptionally well when in manual-focus mode thanks to the short travel of the focus rings and the clear stops, just like a manual lens. I used all three part of the time in manual mode and came away impressed, more so than with any other auto-focus lenses I’ve tested (other than the lenses in Leica’s X and Q series cameras).

I plan to try out all three combinations over the next few months if possible and to add to these preliminary findings. Convenience means a lot and I could certainly see myself carrying a camera such as the Olympus on a daily basis. This is not the case with the SL, nor I suspect with the Fuji (at least with this lens). The 16-55 is hefty by Fuji standards, especially in comparison with the lightweight “kit” zoom, the 18-55, and the longer-reach and also weatherproofed 18-135mm.

Yet I am drawn back to this trio of heavier lenses by the wider 24mm (equivalent) angle of view they offer. If you want to cover all bases, from 24 to near 90, these are the lenses you will inevitably choose. Instinctively, I feel a bit short changed by a 28-70 or even a 28-90. The Leica is perfect in covering every focal length but the others aren’t far behind and are the do-all workhorses for their respective sensor sizes.

Thanks to Andy Sands and his team at Chiswick Camera Centre who did the product shots and without whom this comparison would not have been possible. If you wish to make a direct comparison between the Fuji and Olympus rigs this is the ideal place to go (next to Chiswick Park station on the District Line).

- Subscribe to Macfilos for free updates on articles as they are published. Read more here

- Want to make a comment on this article but having problems? Please read this