Mount Everest and the countless attempts to conquer the world’s highest mountain have been gripping the imagination for at least the past hundred years. And the first successful attempt by Sir Edmund Hilary (citation) in 1953 set the seal on Coronation Year. It was the year when the gloom of the Second World War was finally shrugged off in Britain. A new Queen was on the throne, and the conquest of Everest was seen as a defining moment for a new age.

But 1953 was just the midpoint in a century of excitement and adventure. Macfilos author Wayne Gerlach wrote about his recent trip to Mount Everest, outlining the mystery of the Mallory and Irvine expedition of 1924 and the tantalising possibility of finding the lost Kodak camera from that fateful journey. I was fascinated by the article, and I remember Wayne’s words:

It is now much easier to visit the north side of Everest than it was for the British expeditions of the 1920s. However, the route is still the same, so it is thought-provoking to stand at historical locations where those early expeditions saw Everest for the first time, nearly a hundred years ago. Very little of the landscape has changed, so one can accurately imagine the view as it was back then.

Hugh Boustead

I was fortunate, many years ago, to hear at first hand the personal recollections of a member of the 1933 Everest Expedition about his return journey across the Tibetan Plateau in springtime.

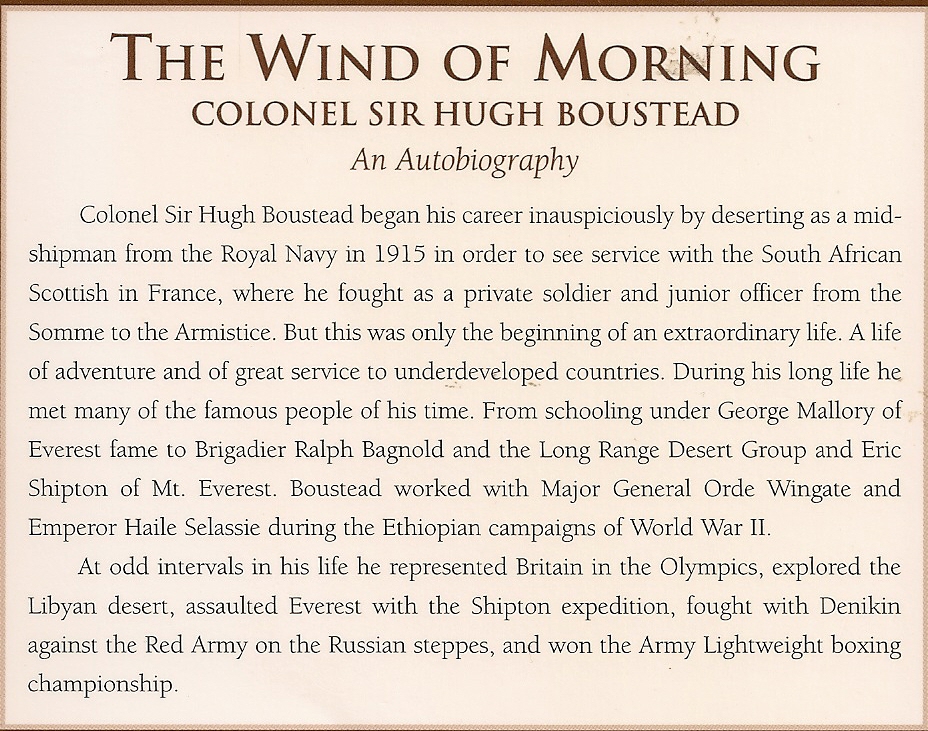

In late 1977, I served with B Squadron, Oman Gendarmerie, stationed at Buraimi Oasis, situated on the border with the UAE. Just ten miles away, in the eastern shadow of Jebel Hafeet, lived Colonel Sir Hugh Boustead, KBE, CMG, DSO, MC and bar.

His grand address was: Royal Stables, Miziad, Al Ain, Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Recollections of an extraordinary man

Sir Hugh was an extraordinary man and, as he said to me, he “wrote his life”. The book was called, “The Wind of Morning”.

It was Sheikh Zaid of the UAE who offered Sir Hugh, towards the end of his life, a home where he could look after the President’s horses and enjoy his retirement amongst the Arabs he loved so much.

Click on images to enlarge

Shortly after I arrived at Buraimi, I was introduced to Sir Hugh, and subsequently, I visited his home on many occasions during that time in 1977. He often had a stream of visitors, but on one occasion, I sat down to dinner with him alone; waited upon by his steward.

He was 82, and I was 29. He loved recounting the exploits in his extraordinary life, and I particularly remember him telling me about the 1933 Everest Expedition. It was just two years after the successful 1975 British ascent from the south-west face. On his coffee table was the book, “Everest The Hard Way”, so Everest was a natural conversation topic.

What sticks in my mind, particularly after some 44 years, is his description of the return journey across Tibet on a pony, having suffered frostbite. He and the rest of the climbing party had been pinned down in atrocious conditions at camp 5, which had been pitched at 25,700 feet.

If I may, I will quote extracts from Sir Hugh’s autobiography. They are as he told me as we sat in his desert home over a most agreeable dinner.

“Outside the tent at camp 5 we gazed over a scene which looked like the top of the world. The great mass of Makalu and all the wilderness of Himalayan peaks were ranged around us, seen through mist and driving snow. A white sheet of snow flew like a pennant from the top of Everest, in effect a snow curtain blown by the wind. The summit looked so near across the great yellow slabs of the last gully, which led up to it.

“After 3 days the food in camp had given out and the porters were in poor condition. News had come that the monsoon was upon us and Hugh Ruttledge sent a message up telling us to come down. My own time had run out and I had to set off without delay for Darjeeling. The descent to the base camp was painful to a degree. I had not realised till then that I was suffering from frostbite, not severe but extremely painful and increasingly so as I went further down. Each time I put my foot on the ground it was like treading on red hot bricks.

“This was the end of the attempt for me…

“At base, a horse transport convoy was arranged with the local Tibetans because I could go no further on foot…

“The journey across Tibet was one of the most memorable and enchanting of its kind I can remember, despite the fact that I had to be lifted onto a Tibetan pony at 8 o’clock in the morning and lifted off at noon for lunch; lifted on again at 1 o’clock until we made camp at 5.

“Rivers that had been iced up when we crossed were running streams with teal and mallard diving in their waters. The great white plains of the plateau were now green with new grass and violet with flowers. Mountains 2 or 3 days’ journey away looked as if you could hit them with a stone. Wild asses, gazelle and Ovis Ammon roamed over the countryside and to the south the snow peaks of the Himalayas were spread in a jagged chain of ice particles.

“For the past two months the only sounds we had heard were the roaring of the winds, the gurgling of a glacier or the fall of ice and rock. We saw no sign of life other than the occasional chough up on the high rocks. We had breathed with increasing difficulty as the height increased, but here although the altitude was 15,000 feet, every breath of air seemed to fill me with so much life I felt I could never be tired again…

“We rode solidly for 8 hours a day, crossing these vast and beautiful plains. I felt I could have done another 4 or 5 hours daily without fatigue. My pony had been taught to tripple the easiest pace for long trekking.

“It was not until we came across the Natu La down into the forests of the Himalayas, already rain-swept by the first monsoon showers, that the pain of the frostbite began to disappear in the damp of the warmer atmosphere…

“When I eventually reached Calcutta my feet were totally recovered.

“I arrived back in the Camel Corps in July. It was not until the following year that I saw General Norton again. He was now in the War Office. We talked for a long time and he asked me what I thought was the most enjoyable part of the expedition.

“I told him of the return journey across Tibet alone, with all the immense contrasts it held compared to the weeks of striving among the snows. I found that my senses had been so keyed up by the weeks of high altitude I was able to appreciate all the beauties of the Tibetan spring in a way I could not describe. Norton entirely agreed, and said, ‘I found exactly the same’. The whole expedition was worth the return journey across the enchanting plains in spring.”

Later at dinner, I asked Sir Hugh about the 1924 expedition and whether he thought Mallory and Irvine had actually reached the summit. He said, “We found an ice axe probably belonging to Irvine”, but offered no other opinion except to say, “We shall never know”.

Sir Hugh died on 4 April 1980 in Al Ain, aged 84. A memorial service took place in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral later that year which I attended. Just as the service began a loud voice behind me was heard to say, “And then he ate his camel!”.

What a remarkable character he was.

A one-to-one dinner spanning two generations. Special.

And special that you’ve documented memories that would have otherwise been lost.

The world of exploration was much harder a century ago. But hardy souls just got in with it and did it.

Also enjoyed the accompanying images.

Thank you. I am glad you enjoyed the article.

Chris

William,

Thank you for your incisive observations about the connections between cultures. Are you sure it wasn’t natural Irish charm which invoked the term of endearment; brother?

To be serious for a moment, I would encourage you to write an article which encompasses the themes you have already mentioned. If it was of interest, I could let you have my thoughts on the do’s and don’ts of Gulf Arab customs, for example, not showing the souls of your feet, correct greetings, drinking coffee etc.

Chris

Reading this, I was immediately reminded of Wilfred Thesiger and his travels around the ‘Empty Quarter’ and his various books such as Arabian Sands as well as his wonderful photographs. His name came up for mention more than once during my time in the Middle East. Thesiger was born in Addis Ababa and, like Sir Hugh, he knew Haile Selassie. I am sure that Boustead and Thesiger must have known one another. There is a photo on Thesiger at Haile Selassie’s Coronation in 1930 as a very young man amid one of the most medal be-decked British delegations that I have ever seen. Boustead may have been there, but I did not spot him.

I would like to mention here a book called ‘To the Ends of The Earth, 175 years of Exploration and Photography’, published by the Royal Photographic Society, which somebody gave me as a present while I was in Doha. It covers a lot of the era which you describe in your article and is full of ‘brave chaps’ out there ‘discovering the world’.

Reading about Thesiger and his trips with the Bedu, I was reminded that only last week I was describing Bedouin culture in a Zoom talk which I gave showing my photos from Qatar and Syria. My theme was the extent to which Bedouin culture still informs the present day culture of the Gulf States. I won’t go into the details here, but I had some interactions with the Bedouin over issues like camel racing and they reminded me very much of some of the population of my own little island.

Thanks Chris for this insight into the days when European (well British anyway) culture was being replaced by the native Bedouin culture which is still there today. You just have to scratch below the glossy towers of Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Doha etc to find it.

William

I agree William. Old men in the UAE will speak of the day their little sister or brother died in the desert of an injury because the nearest hospital was hours away. Only a couple of generations ago; how the UAE has changed. It is said that regarding glitz and pace of life Al Ain is to Abu Dhabi city as Abu Dhabi city is to Dubai city.

William,

Yes, Thesiger was very much of a legend out in Arabia. Indeed he visited Oman when I was there but I didn’t meet him. I have just read that Hugh Boustead did not in fact meet Haile Selassie until 1939, in Khartoum, when Ord Wingate was planning the invasion of Ethiopia to reinstall the Emperor. As we know, the Italians had annexed Ethiopia in 1937.

When I was in Oman the Bedouin culture prevailed and it was we expatriates who followed and respected their culture. Perhaps now this has changed in the name of tourism, though as you say, the Bedouin culture is still deep rooted.

When I was in Oman the population was under 1 million, now it is 5 million. The change in Arabia has been dramatic in the last 40/50 years.

Thanks Chris. There are a lot of Bedouin concepts still holding strong in the Gulf, including the tribe with the Sheikh as leader and the sharing and circulation of wealth among the tribe. The famous Bedouin saying ‘I am against my bother, my brother and I are against our cousin, my brother and I and our cousin are against the stranger’ does not necessarily indicate a warlike people, but rather a hierarchy of loyalties.

If we meet up and have a few beers sometime we could swap stories, particularly about their love for their camels, the animals that kept them alive in their many centuries wandering the deserts. Next up come their falcons which are not just for sport, but were actually food hunters for them as they crossed the barren wastelands. The main Bedouin tribe I dealt with were the Al Marri, who are called the Al Murrah in Saudi. There is also an old saying about them which goes ‘In the skies, the telegraph, on the ground the Al Murrah’. In Qatar, members of the Al Marri tribe have risen to high positions within the State, including becoming Attorney General and Ambassadors.

I could say a lot more, but, despite the shiny skyscrapers, the old culture is always there. I also found that my friends in Qatar always respected my culture and my religion. I have fond memories and still maintain contact with them

William

William

Could there be a written article entitled; “The extent to which Bedouin culture still informs the present day culture of the Gulf States”?

I for one would be very interested in reading such an article. Does the editor have a view?

Chris

I will think about it. I have a lot of stories revolving around camels including a proposal to put SIM chips on roaming camels and then having to make regulations to allow higher powered wireless for the robot jockeys on the local track where 10 km races were not uncommon. The real story, though, is that people whose fathers lived in tents and who grew up in houses with dirt floors themselves are now sitting down and having tea with the likes of Bill Gates. They have come along way in a very short time, but they retain the essentials of what is a very old culture. In the film Lawrence of Arabia Alec Guinness as Faisal captured the cultural essentials perfectly. Lawrence and Thesiger and I am sure Boustead as well had the emotional intelligence to cross the bridge between two very different cultures. Lawrence’s The Seven Pillars of Wisdom has been called the finest insight into the Arab mind written in English. Some Europeans and other Westerners never make the cultural connection. The day you know you have made that connection is when an Arab calls you ‘brother’. I was first called that over a dozen years ago and the man who did that still calls me that even though I am retired in Ireland and he is running a very important State body in his own country. I am sure that you became a ‘brother’ to your colleagues in Oman. Crossing that divide does not mean abandoning your own culture. As I mentioned already they have great respect for other cultures and religions. I had a very interesting experience one time going with a Qatari delegation to visit one of the Papal Palaces in Rome, which fascinated them.

I will think about the article. I am sure that you had a lot of interesting experiences yourself in Oman in the 1970s. I always found the Omani people to be more immediately friendly than other Gulf peoples, but you can cross a bridge with the others, it just takes more time.

William

Thanks for this Chris. I lived in Abu Dhabi for a few years and most recently in Al Ain in 2017. I was fortunate to know Jocelyn the wife of Edward Hendersen, both good friends of Sh Zayed. Edward wrote of his experiences in his autobiography Arabian Destiny which, if you haven’t read it already, I am sure you would enjoy.

Kevin,

Would you call yourself an Arabist? I have just read the obituary of Edward Henderson and he would certainly have known Hugh Boustead. I have found a second hand copy of his book on the internet so I will most probably buy it.

Did you recognise Jebel Hafeet in the photograph? Certainly it was an overbearing feature of Al Ain. I have just looked on Google Earth to see how Al Ain has spread and the development is remarkable since I left there some 40 years ago.

Chris,

I wouldn’t call myself an Arabist in the strict sense of the word because I don’t speak Arabic sufficiently well. I have however spent years working in various Arabian Gulf countries and as well as being attracted to the desert I respect the peoples and their cultures. Although in many countries the peoples principally looked to the sea for their livelihoods rather than to the desert.

I did recognise the Jebel and was always interested in how it looked day by day as the weather changed. I’m thinking of preparing a short article on Al Ain and its oasis, the town has a rich history going back hundreds of years.

As an aside the term Bedouin has a specific meaning and I recommend that it be used with care on this public forum.

I agree that the name Bedouin can have particular meanings and connotations, but the boundaries are blurred and when it comes to culture they are even more blurred. In Qatar, where I was, the Bedouin and Bedouin culture were held in very high esteem, all the way up to the Royal Family. For a period, the young Heir Apparent, now Emir, who at the time was Chairman of our Board, attended camel races near Palmyra (or Tadmor as the Arab people call it) in Syria, where like minded people from various countries held international camel racing. In Qatar the people who organise camel racing had attendees from Saudi (‘brothers’ from Saudi) late last year, even before the Saudi boycott of Qatar had ended. Despite differences there are common cultural features at work across national boundaries in Arabia. There were issues in the past where Bedouin regularly crossed national boundaries, but my understanding is that at one point they had to choose one or other of the Gulf States and that this may have led to some issues of conflict. We met some Bedouin in Petra and one of them introduced himself as the son of the New Zealand woman who wrote the book ‘Married to a Bedouin’, which is well worth reading for further insights. I can also talk about a former army officer, working for a TV station, who thumped his chest with pride and started his address to me with ‘I am Bedu’ before describing an issue about roaming camels. Finally, describing people as engaging in Bedouin cultural pursuits does not mean that you are calling them Bedouin. I am fully aware of all of the history and cultural sensitivities and had no issues in that respect while I was living in the region.

William