For twenty years, from the early eighties onwards, visitors to London Heathrow could marvel at the sight of the striking model of the British Airways flagship, Concorde. The Heathrow Model Concorde stood in the centre of the roundabout connecting the M4 motorway with the tunnel to the terminals.

One day, shortly after its bigger, supersonic siblings were withdrawn from service, G-CONC, the perfect little replica, was carted off, but not to oblivion. British Airways had donated the model to the Brooklands Museum in Surrey to recognise the huge part Brooklands had played in the development and manufacture of all Concordes. Over the next few years, a team of up to 30 volunteers restored the Heathrow Model Concorde to its former glory.

Nearly a decade ago, in 2012, the model found a permanent home as the gate guardian to the Brooklands Museum. It now sits at the entrance to Brooklands Drive and welcomes visitors as it once impressed international travellers entering London Heathrow. Yet it serves a double purpose—to provide a welcome and a pointer to its full-size sister inside the museum.

No visitor can overlook the full-size Concorde that sits in the aircraft park, alongside many other historic aircraft. Yet not many realise that this is the first production Concorde to take to the skies. It was the first to carry over 100 people at supersonic speeds. Now, it represents the close ties between Concorde and Brooklands.

Concorde HQ

Brooklands was a pivotal force in the development and production of the Anglo-French aircraft. Sir George Edwards and his development team were based at Brooklands and over one-third of the airframe of all Concordes, whether they eventually emerged from the British or French factory, was constructed at the Weybridge site. All the wiring looms—90 miles of wiring per aircraft—were made and installed at Brooklands and the cockpits were fitted out there.

Brooklands is now regarded as the headquarters of the Concorde preservation movement, with the museum’s aircraft standing as the most senior of the 16-strong fleet currently preserved and on display in various parts of the world. Almost all spare parts are stocked at Brooklands, and the museum preserves manufacturing equipment, engine maintenance tools and tyre-changing equipment. The volunteers, many of them retired British Airways engineers who worked on Concorde in its heyday, are there to ensure that this aircraft remains in pristine condition.

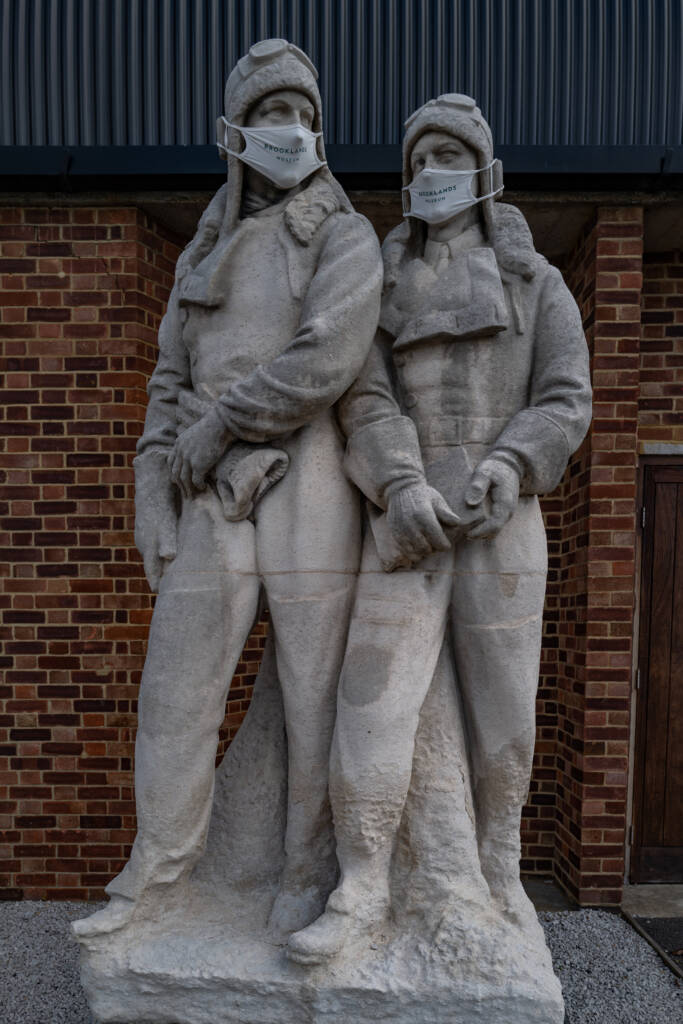

Last Friday, I paid my first visit to Brooklands after five months of Covid-induced closure. And, as usual, I was welcomed by the Heathrow Model Concorde as I entered Brooklands Drive.

Until May, the museum is open only on Fridays and Saturdays, with pre-booking essential, and visitors are restricted to outside exhibits, including Concorde and the other historic aircraft in the park. Sadly, only glimpses of the motoring exhibits, through the open doors of the museum halls, are currently allowed.

The museum hopes to be fully open again in May as Covid restrictions are gradually removed following the dramatic reduction in infections and serious illness.

What’s in a name

Reflecting the treaty between the British and French governments that led to Concorde’s construction, the name Concorde is from the French word concorde, which has an English equivalent, concord. Both words mean agreement, harmony or union. The name was officially changed to Concord by Harold Macmillan in response to a perceived slight by Charles de Gaulle. At the French roll-out in Toulouse in late 1967, the British Government Minister of Technology, Tony Benn, announced that he would change the spelling back to Concorde. This created a nationalist uproar that died down when Benn stated that the suffixed “e” represented “Excellence, England, Europe and Entente (Cordiale)”. In his memoirs, he recounts a tale of a letter from an irate Scotsman claiming: “You talk about ‘E’ for England, but part of it is made in Scotland.” Given Scotland’s contribution of providing the nose cone for the aircraft, Benn replied, “It was also ‘E’ for ‘Écosse’ (the French name for Scotland) – and I might have added ‘e’ for extravagance and ‘e’ for escalation as well!” — Wikipedia

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Concorde has featured a few time in Secrets of the Transport Museum https://yesterday.uktv.co.uk/shows/secrets-of-the-transport-museum/episodes/ (I’m not sure if you can watch online outside the UK).

Recommended reading is Concorde the complete inside story by the chief test pilot Brian Trubshaw (ISBN 9780750989022).

My memories of Concorde relate to the long corrugated tube from Terminal 1 in Heathrow connecting the main building to where the Irish flights took off and landed. This was affectionately and mockingly called the ‘Paddy Tunnel’ by generations of Irish passengers. We did not mind it as we knew that when we were at the other flight end we would be one step closer to home. Anyway, if a Concorde took off or landed while you were in the tunnel the whole thing would shake as though the Second Coming had commenced. If you were at the flight end of the tunnel at night you could see the flames from the aircraft’s engines through the windows.

I have seen a Concorde flying over my house here in Dublin as a lot of the UK-US flight routes go over Ireland. The economics of the Concorde did not work out. There have been proposals to build hyper-speed and near-space aircraft which would need to be packed to the gills with passengers for the economics to make sense, but will there be a rush to go there post-Covid?

William

I would think people are itching to travel and when they can relatively safely air travel will see a boom.

Hi William,

Post COVID, to pack people in, you can see each passenger sitting in a plastic cubicle so that the operators can maintain numbers. And while it sounds perhaps a little daft, do not underestimate where some companies will go to keep their coin rolling.

Dave

Ah another piece of genius human engineering, that for some unfathomable reason we failed to modernise.

I am sure it also became slightly unsafe on the basis of upkeep, and these things need close scrutiny when they push the boundaries of science.

If only we could build new ones, even slightly more advanced, instead of our aviation fixation of putting sky juggernauts in the air.

It’s become clear over the last year at some point I need to visit Brooklands.

If you do envisage a trip to Brooklands let me know and maybe we can arrange to meet. I can even admit you as a guest.

“..I am sure it also became slightly unsafe on the basis of upkeep..” ..I think one of the reasons – besides cost – for retiring them was the vulnerability of the fuel tanks ..remember? ..didn’t a wheel or part of the undercarriage rupture a tank in Paris with a full complement of passengers on board ..and didn’t it burst into flames?

Ah yes; here it is on Wikipedia: “Air France Flight 4590”. All 109 people on board died, and four more in the hotel which it crashed into. Wikipedia has a photo of it taking off, and on fire.

The End.

That was indeed the incident that put the kibosh on Concorde. After that, I don’t think many people would have rushed to pay £7,000 for a round trip to New York for the sake of saving three hours… the great pity of the Paris incident, as I seem to remember, it was one of those short jollies rather than a regular flight. Just so people could say they flew on Concorde.

Yes, sadly, a small failing had a massively catastrophic outcome. The thing for me, is surely we retire the current fleet, or adapt them, and build a new fleet that has new advances, and rectifies some of the areas of risk. That is the usual human evolution of all things science orientated.

Perhaps one day, some one will see fit to reintroduce a very modernised variation that is viable for flights once more.

I was at White Waltham airfield for an air show to mark the Queen’s Silver Jubilee. The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh arrived in an aircraft of the Queen’s Flight, an Andover i believe. Despite all of the wonderful flying displays it was Concorde which stole the show. It came down on a landing approach with nose and wheels down and passed across the airfield no more than 100 feet above ground. Just magnificent. For those not in the know White Waltham is a grass airfield. My biggest regret is not taking one of those flights towards the end of its career round the Bay of Biscay.

I have just had a look on Google Earth and seen the actual Concorde and a VC10. How did they get the planes there? At the Duxford museum, the airfield is large for exhibits to land, for example the B52 in 2008.

I believe the VC10 was the personal plane of Sultan Qaboos of Oman. Am I right? I remember being told by somebody in the know, that Qaboos once went on a foreign tour from Oman and all his ministers, a military guard and band were at the airport to bid him farewell. The VC10 duly took off to waves from the onlookers. Ten minutes later a small jet took off carrying Sultan Qaboos. He took his own personal security very seriously.

I think you are right. It is certainly a Gulf potentate’s plane and I’ve walked round it a few times. As for how they got the planes there, I don’t know. There is a runway but too small for Concorde, so they must have been brought by road. I must ask next time I am there.

The fun of Macfilos – it can jog memories. Thanks Chris and Michael.

In the late 70s we were on our first overseas adventure, living a handful of miles from Duxford. At that time the runway was significantly shortened as the M11 motorway was being constructed at one end.

And what was the last plane to land there on the long runway? Yes, Concorde 101. From then on trapped in by a new motorway built decades early in anticipation of our Editor’s new Tesla 😀

I don’t remember where it was going (I did once know), but at Isleworth one day (south west London, near Mike, many years ago) I saw a Concorde body – sans wings – whaddya call it? ah; the fuselage, being taken ..very slowly.. down the Thames on a barge. It had been, apparently, dismantled at Heathrow, but the body & wings were thought too awkward or disruptive to move any long distance by low loader, so they were taken just to the river, and then floated downstream to somewhere below London where they could be transported further by road.

I used to watch it fly overhead, as we were pretty much under the flightpath, till the path moved slightly after 9/11, and when the wind was in the right direction ..otherwise, with the wind in the other direction the Queen and Co at Windsor had – or rather have – all the aeroplane noise. We don’t really notice it ..but then, there haven’t been that many Heathrow flights during the year of lockdown. My Beloved once flew on Concorde (..one of those fly one way, then back on the QEII – or the other way round – trips. She said it was tiny and cramped).

The answer is, the VC-10, the One Eleven and the Vanguard were all flown in, in 1987, 1994 and 1996 respectively. For the VC-10, they made missed approach to get an idea of it, went around and landed second time. By the time of the Vanguard, the runway had been shortened by the building of Wellington Way across it. Some street lamps and I think trees had to be uprooted to remove obstructions just before the “displaced threshold”. In fact the Vanguard touched down short and nearly put its gear straight in a hole where a tree had been temporarily removed.

Some videos of the One Eleven and Vanguard arriving here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLDgkAqKJiI

https://youtu.be/fmakSwlYLs0

I have photos of the VC10 arrival, but they’re not mine so I cannot really share them.

Sorry this was delayed, Toby. The link meant it was flagged for moderation and I didn’t see it until Saturday morning.

That was a beautiful plane. We still have one near Roissy Charles de Gaulle airport near Paris. Wish they went on building these planes. It would make long distance travelling much more comfortable.

And expensive. That was the problem. I flew Concorde once from Washington DC to Heathrow. While it was an interesting experience, I would have paid the £3,000 oneway fare. Luckily I was on a BA staff ticket, but, faced with that cost I would sooner have spent seven hours being pampered in first class on a 747. My time es never that valuable!