Have you ever wondered why images in black and white hold such fascination for photographers or why many consider them the highest form of photographic art? New research in the field of paleogenetics could hold the answer. The revolutionary discovery of an ancient group of hominids, Homo monochromensis, has brought together the disparate fields of palaeontology and photography, with huge implications for both.

Palaeontology and photography

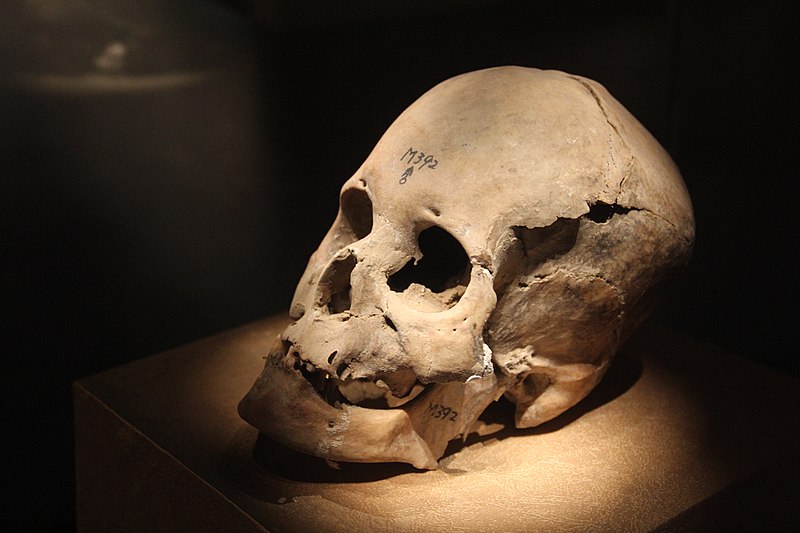

Two years ago, at the beginning of April 2021, a multi-national team of palaeontologists led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig made a remarkable discovery deep in a cave in Western Germany. They unearthed the skeletal remains of an ancient humanoid form, hidden for over eighty thousand years. Over the last century archaeologists have uncovered many such ancient remains, slowly piecing together the story of human migration from Africa. But this one broke new ground.

In collaboration with David Reich at Harvard University, they extracted DNA from the petrous bone of the skull inner ear. This allowed them to undertake a complete sequencing of the male individual’s genome. Detailed genetic analysis enabled assignment of his likely age and health status, nowadays routine and unremarkable accomplishments. However, buried in that DNA sequence, they also discovered something that was anything but unremarkable.

Cave Paintings

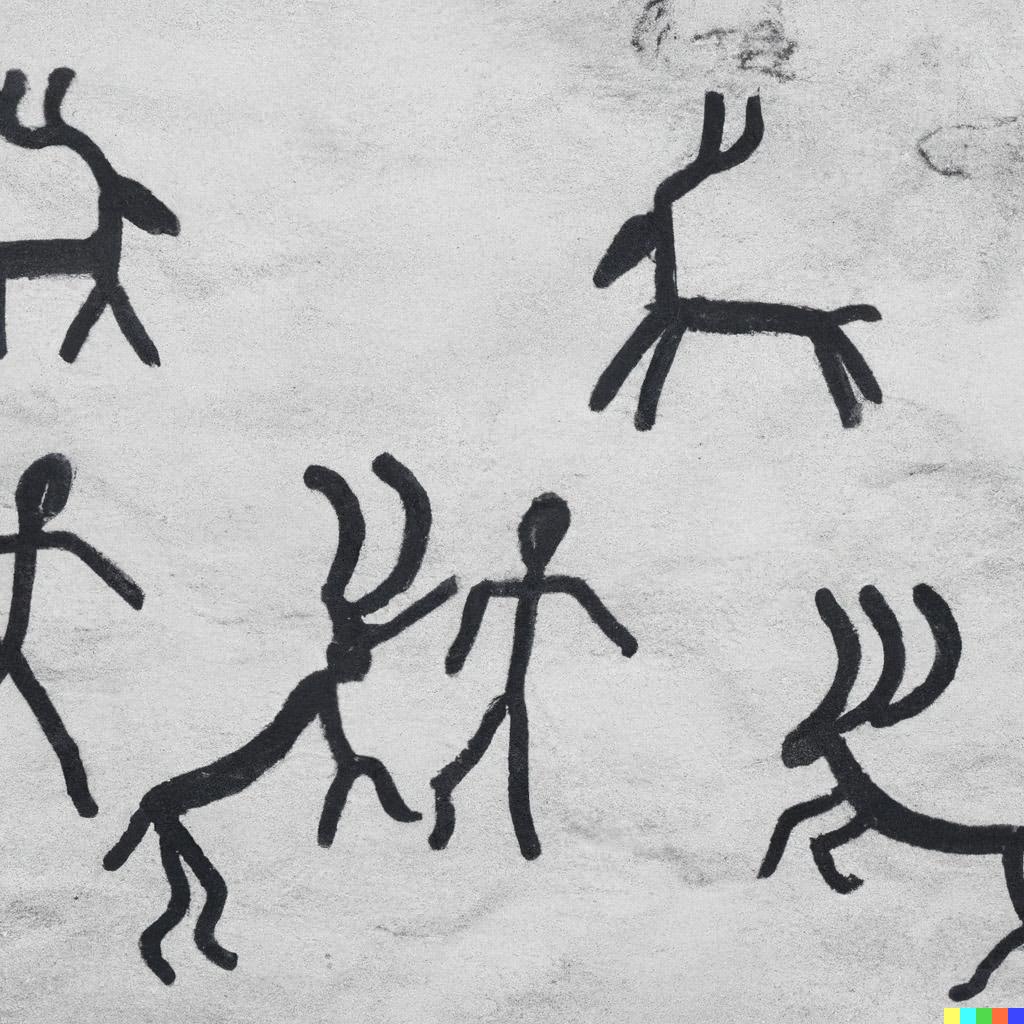

In parallel with efforts to recover DNA samples from the fossilized remains, the investigators explored a network of caverns linked to the burial site. In a distant chamber, they found wall paintings depicting both abstract images and stick-figure representations of tribal life. Strikingly, the paintings lacked any colour, unlike those found in the Chauvet cave in France, which they predated by almost sixty centuries.

The neolithic artists responsible had rendered them entirely in charcoal, derived from charred twigs, on a background of chalk. Here was a tiny clue, a piece of the jigsaw that was coming into view as the early results of the sequencing efforts began to emerge. The findings hinted at a hitherto unsuspected link between palaeontology and photography.

Missing Genes

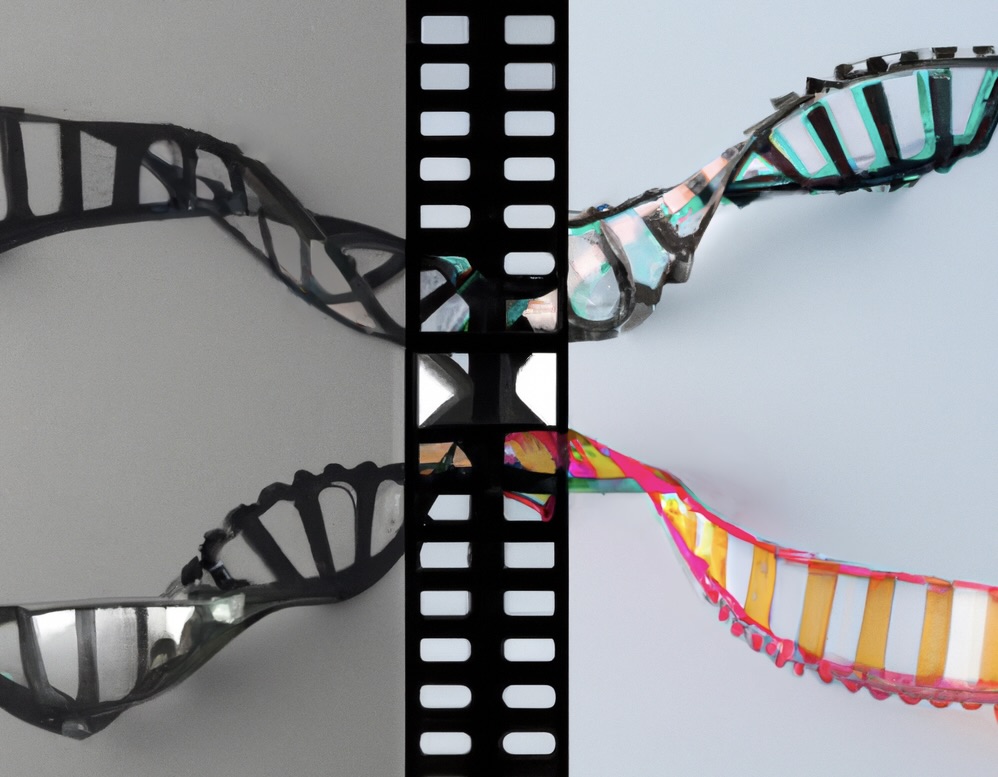

As the Harvard and Leipzig teams compared the DNA sequence of this newly discovered hominid with a reference genome from a modern human, they realized two crucial genes were completely absent from his X-chromosome. These genes, OPN1LW and OPN1MW, encode two of the three photoreceptor proteins required for colour vision. Their conclusion was inevitable and shocking.

The hominid they had discovered had only been able to see the world in black and white.

Although modern humans and other primates have evolved to use trichromatic colour vision, lower species do not possess this ability. The discovery of a new member of the Homo family which lacked colour vision was a revelation. In recognition of this momentous finding, the new hominid was named Homo monochromensis.

Although we cannot be certain, it is likely that artists from within the Homo monochromensis family were responsible for the nearby black and white cave paintings, which were dated to a similar era. The absence of colour in their art would be consistent with their inability to recognize colour in the prehistoric world around them.

The discovery of Homo monochromensis has puzzled the field of palaeontology. What became of this distinctive branch of Homo? Why did they suddenly appear and then disappear from the fossil record? Perhaps they were out-competed by the ancestors of Homo sapiens, whose colour vision conferred an evolutionary edge. Perhaps they interbred with the ancestors of Homo sapiens, and their genetic signature was diluted or lost.

But could there be vestiges of that monochromatic visual perception detectable in the genomes of modern humans?

Palaeontology and photography hiding in the data

In search of an answer, scientists have conducted statistical genetic analyses of large public-domain databases such as the UK Biobank. The biobank contains detailed biological, behavioural and genetic profiles of over half-a-million UK subjects. This resource has become a powerful tool for the world’s genetics community.

Recent analyses, called genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have revealed surprising results. Subjects who described themselves as photographers possess an unusual set of variants in genes encoding proteins within the visual cortex. Perhaps not surprisingly, these correspond precisely to variants found in the genome of Homo monochromensis.

Furthermore, in a follow-up study, the Harvard team anonymously interviewed several hundred people within this subgroup. In response to the question: “Have you ever felt a deep, primal need to take photographs in black and white?” over seventy-five per cent answered “yes”. Even more remarkably, over fifty per cent of that group answered “yes” to the question: “Do you own, or have you ever owned, a Leica Monochrom camera?”

This association between genetic makeup and photographic inclination is highly statistically significant. It seems that although this extraordinary member of the Homo genus died out millennia ago, the influence of their genes may still be felt today. In some sense, Homo monochromensis still walks among us.

Have you ever felt a primal urge to take photographs in black and white? Do you think it is possible that your genetic makeup influences your photography? Have you ever taken part in a survey about your photographic habits? Do you know what today’s date is? Let us know in the comments below.

Read more from Keith James

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Very nice April Fool’s joke Keith, thank you very much. Not so easy to come up with something in the Leica context when a camera with a Mickey Mouse design is meant seriously. And now I’m putting my revolutionary black and white interchangeable sensor in my camera, I just found another roll of Tri-X in the fridge.

I thought first photo Mikes cousin YORRICK!

A couple of years ago one of Ansel Adam’s descendants was fascinated by his family’s history so signed up with Ancestry.com to do the family tree and also take the DNA test that gives you an indicator of your heritage.

On a very early April day he discovered that his great grandfather Ansel Adams carried the Homo monochromensis gene and from that discovery many things about that great man became clear.

Further research showed an earlier descendent also carried the same Homo monochromensis gene but he had been practicing lawyer and later politician who had developed the theory that no answer can ever be purely black or white but must explore and develop all shades of grey of the argument.

The journey to discover our past is a wonderful thing. But the person who discovers it first can never be described as a fool.

Love it! Perhaps I should get my own DNA analyzed.

Nice ‘send-up’ of MACFILOS articles

Ahahahahaha! (..Worst Macfilos article – ever!)

Yeah this one tries too hard. Well, I guess, you win some, you lose some. 😀

No; well constructed: I was just referring to Keith’s previous article!

Absolutely fascinating! i’ve certainly considered putting one of my cameras on permanent monochrome and learning to see that way. Shall now do, thanks to your article.

Today is the anniversary of the date that Canaletto created Photoshop. And that one is partly true.

William

I thought Canaletto was a pastry maker in Florence who originally opened “The FiloShop” named for the type of pastry he preferred.