It’s not hard to find a history corner in London. They’re everywhere. But there is one small cluster of buildings, nestling on the bank of the River Thames in the suburb of Hammersmith, which has seen more contributions to the arts and science than most. It is a true corner of history with an eclectic mix of firsts.

Surrounding the ancient Dove public house is the birthplace of the world’s first electronic “web”, the kernel of a major 19th Century art movement and the location of a unique experiment in typography that provoked a murky 100-year mystery.

I call it Dove Corner, although I suspect no one else does. It lies at the end of Upper Mall, part of the riverside road from the old village of Chiswick, just before Furnivall Gardens (also spelt Furnival), which, in earlier centuries, was the course of the Stamford Brook, feeding into the Thames at Hammersmith Creek. The creek was the site of an active fishing trade up to 200 years ago but was finally filled in and turned into gardens in 1936.

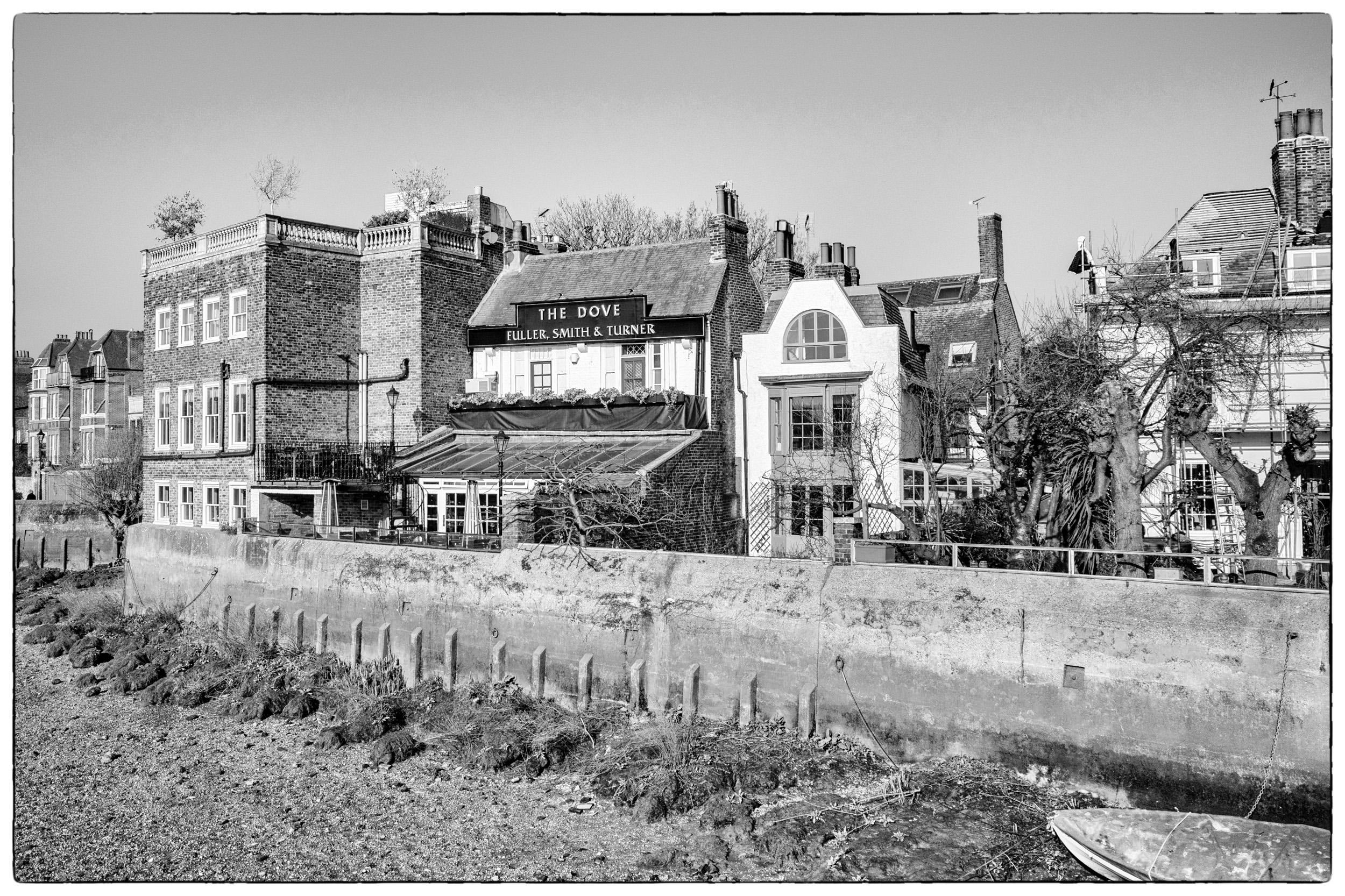

History Corner: The Dove public house

The Dove pub itself is one of the most historic hostelries to be found along the River Thames in London. It dates back to the 17th Century and has a full hand of claims to fame, including serving as a discreet royal trysting house and a quiet location for the composing of a rousing patriotic song.

For over 90 years, the pub was known as The Doves because of a sign writing error in 1860, probably accounting for the naming of The Doves Press later in the century. Now, the other birds have flown, and the One and Only Dove again presides over the narrow Thames-side passage as it has done since the 17th century.

This is a pub that should be on anyone’s bucket list. It is home to the smallest bar in England and offers a wonderful (but small) river terrace for summer drinks and pub food. Yet few of the walkers and cyclists squeezing through the narrow passageway in front of the pub’s door realise the full extent of The Dove’s connection with world events.

History Corner: The Electric Telegraph

The world’s first true communications internet, the electric telegraph, was first demonstrated in 1816 across the road from The Dove. Sir Francis Ronalds constructed an intricate web of wires, eight miles long, in the back garden of his home, which is now known as Kelmscott House. He proved that electric signals could travel long distances and be employed as a means of instant communication.

Yet his invention was written off by the British government, and Ronalds never saw the fruits of his labours. It was left to others, on both sides of the Atlantic, to claim his birthright.

Above: The garage or stable adjacent to Kelmscott House bears the commemorative plaque (right) above the top-floor windows (Ricoh GRIII left, Lumix S5 and 24-105mm right)

Key to Ronalds’ disappointment was the year. After the 23 years of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, Britain was in no mood for a new-fangled improvement in military communications. Napoleon had been defeated the year before at the battle of Waterloo. Peace was assured, so why spend money on an invention that could have only one possible use — in war? John Barrow, secretary to the Admiralty, wrote that “telegraphs of any kind are now after the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars totally unnecessary, and that no other than the one now in use, a semaphore telegraph, will be adopted”.

After this rejection, the invention languished for twenty years, and as a result, Sir Francis Ronalds does not get the credit he deserves. It fell to two other Britons, William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone, to patent the first practical telegraph in 1837. The same year, Samuel Morse registered his patent for the electric telegraph. But the first demonstration of the invention’s potential took place in Hammersmith, within hailing distance of The Dove.

Historic Corner: The Arts & Crafts Movement

Kelmscott House in Hammersmith’s Upper Mall was the home of William Morris, the English reformer, poet, and designer. Morris was a leading protagonist of the 19th-century aesthetic movement, Arts & Crafts. In 1861 Morris founded a firm of interior decorators and manufacturers — Morris, Marshall, Faulkner, and Company — which later became Morris & Co. The company was dedicated to renewing the spirit of medieval craftsmanship.

The Arts and Crafts movement spread from Britain across the Empire and later to the rest of Europe and America. It flourished in Europe and North America from 1880 to 1920 and is the root of the Modern Style, the British expression of what later came to be called the Art Nouveau movement.

Historic Corner: The Doves Press

The story of Doves Press, itself an offshoot of the Arts and Crafts movement, is a murky tale which “bears all the hallmarks of a story by Edgar Allan Poe”. The typography website, Typespec.co.uk, outlines the background:

The Doves Type legend is one of the most enduring in typographic history and probably the most infamous. It’s the story of a typeface and a bitter feud between the two partners of Hammersmith’s celebrated Doves Press, Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson and Emery Walker, leading to the protracted disposal of their unique metal type into London’s River Thames. Starting in 1913 with the initial dumping of the punches and matrices, by the end of January 1917 an increasingly frail Cobden-Sanderson had made hundreds of clandestine trips under cover of darkness to Hammersmith Bridge and systematically thrown 12-pound parcels of metal type into the murky depths below. As one person so aptly commented on Twitter recently, this notorious tale bears all the hallmarks of a story by Edgar Allan Poe.

Typepec.co.uk

Cobden-Sanderson, who is often credited with coining the term ‘arts and crafts’, established the Doves Bindery in 1893. His home and the adjoining bindery lie cheek by jowl with The Dove and a stone’s throw from William Morris at Kelmscott House.

Morris was already heavily involved in typography thanks to an inspirational lecture by the renowned engraver Emery Walker, delivered to the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society in 1888. A fascinating account of Morris’s involvement with Walker and the setting up of the Kelmscott Press in 1890, including the use of photography, can be found on the web page of the Emery Walker House Museum (which lies a few hundred yards upriver on Hammersmith Terrace).

When the Kelmscott Press closed in March 1898, Cobden-Sanderson saw this as an opportunity and, in 1900, set up the Doves Press at No.1 Hammersmith Terrace, near Emery Walker’s home, offering Walker the partnership that he was never given by William Morris.

According to the Emery Walker Trust, “With their clean typography and spacious setting, the Doves Press books strongly contrasted with those of Morris. For a typeface, they returned to Renaissance Italian books, but with the intention, however, of producing a set of letters that looked lighter on the page than their sources. The aesthetic vision was largely Cobden–Sanderson’s, who believed in ‘The Book Beautiful’. Exteriors were stark white vellum with gold spine lettering; inside, there were no illustrations.

Two high points of the collaboration were the 1902 edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost and The English Bible, published in five volumes between 1902 and 1905.

As the story unfolds, Cobden-Sanderson wanted to end his partnership with Emery Walker, who promptly took umbrage. Relations soured, and in 1906 Walker was banned from the premises. Eventually, it was agreed that Cobden-Sanderson, who was the older of the two, would use the Doves type during his lifetime, but it would afterwards revert to Walker. On reflection, though, Cobden-Sanderson found the arrangement intolerable, and he became determined that Emery Walker would never have access to the type.

Thus began a period of several years spanning the First World War, when Cobden-Sanderson would walk to Hammersmith Bridge in the dead of night and throw parcels of the typeface into the river. The increasingly eccentric publisher made 170 such trips and disposed of the entire typeface, weighing over a ton, before his death.

The unique Doves Type was thus seemingly lost to the world forever. But not quite. Fast forward a hundred years and part of the hoard was discovered lurking on the muddy shores of the Thames near Hammersmith Bridge. This video recounts Cobden-Sanderson’s obsession with the Doves Type and its eventual re-discovery by Robert Green. And modern technology has enabled the long-lost font to be recreated in digital form.

T.J.Cobden-Sanderson could not have imagined that his beloved typeface could be digitised in the 21st century and made available to the world of typography. In theory, you could now use the Doves Type to compose your next email.

Above left: The Doves Bindery attached to Cobden-Sanderson’s home. Right, the plaque on the wall of his house, next door to The Dove (Ricoh GRIII)

History Corner: An unwoke anthem survives

In 1741 the Scottish poet James Thomson sat in a cosy upstairs room at The Dove and penned the poem that was later adapted as the lyric of the archetypal patriotic anthem, Rule Britannia. A permanent fixture at the annual Last Night of the Proms at the Albert Hall in London, Rule Britannia remains immensely popular and deliciously unwoke. So far, it has escaped all revisionist tendencies but don’t hold your breath. Here’s a Rule Britannia fix from a typical Last Night (2009, the year in which the Leica M9 was launched, happily enough):

History Corner: A royal trysting spot

So far, we’ve been looking at the factual history surrounding this fascinating historical corner in West London.

But there is anecdotal evidence of some right royal shenanigans taking place upstairs at the ancient Dove public house.

It is said that the present King Charlies III’s immediate numerical predecessor, Charles II, used an upper room at The Dove as a trysting spot where he would meet his mistress Nell Gwyn.

They had two illegitimate children, Charles Beauclerk, later Duke of St Albans and James Beauclerk, who died in Paris at the age of ten. Could it be that the Beauclerks were conceived at The Dove in the rural village of Hammersmith?

Nell Gwyn was one of the first of a new breed, The Actress. The new theatres in London were the first in England to feature actresses; earlier, women’s parts had been played by boys or men. Gwyn joined the rank of actresses when she was fourteen (assuming she was born in 1650), less than a year after becoming an orange girl.

Her good looks, strong, clear voice, and lively wit allowed her to prove herself clever enough to succeed as an actress. This was no easy task in the Restoration theatre; the limited pool of audience members meant that very short runs were the norm for plays. Fifty different productions might be mounted in the nine-month season lasting from September to June. She was reputed to have been illiterate, but her successful acting career and her long liaison with Charles II show that she was a woman who realised her full potential.

History Corner: The location

Hammersmith Upper Mall ends at The Dove, with Kelmscott House on the left. Foot traffic has to funnel down the narrow pipette of Dove Passage, passing the pub, T.J. Cobden-Sanderson’s old house and the home of the Doves Bindery and Press before issuing forth into the wide expanse of Furnivall Gardens. As you can see from the map, The Dove corner is sandwiched between the Great West Road and the river, next to Furnivall Gardens. The William Morris Society maintains Kelmscott House as a museum. Emery Walker’s House Museum and the first home of the Doves Press are several hundred yards upstream (to the left of this map) along Upper Mall.

If you pay a visit to London, this spot represents a most unusual resting place, far from the tourist haunts, where you can savour over three hundred years of history. But The Dove no longer lets out trysting rooms, even if you happen to be the King of England. The nearest Underground stations are Stamford Brook or Ravenscourt Park (District Line), or you can walk along the river from Hammersmith station (District and Piccadilly Lines). It’s advisable not to drive there because there is no parking available.

Join the Macfilos subscriber mailing list

Our thrice-a-week email service has been polished up and improved. Why not subscribe, using the button below to add yourself to the mailing list? You will never miss a Macfilos post again. Emails are sent on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at 8 pm GMT. Macfilos is a non-commercial site and your address will be used only for communications from the editorial team. We will never sell or allow third parties to use the list. Furthermore, you can unsubscribe at any time simply by clicking a button on any email.

Super historical vignettes and atmospheric B&W 1

Thank you, John

Delightful story and photos, Mike!

Thank you, Andrea.

Can not remember the mystery story, but they referenced the MORRIS wallpaper thru out the home. Is this that guy? Love b/w gald c using gr3!

Yes indeed. William Morris wallpaper keeps coming back into popularity. I remember using Morris wallpaper in a dining room in the 1980s.

Hi Mike, I thoroughly enjoyed these interconnected tales about a corner of London of which I was completely unaware. Great photos too! I think there is sufficient substrate here for a film or play about these colorful characters. The story of a ton of typeface being dropped into the Thames is itself worthy of a BBC historical drama! Cheers, Keith

Lovely set of interwoven short historical stories. Makes me want to come back home to visit. BTW. Did you also write a story about Dove Printing and type being thrown into the river a few years ago, or am I imagining things?

Full marks for being a long-time reader. Yes, I have covered various facets of this story on more than one occasion, but I decided to weave them all into one story. Several friends have suggested recycling some interesting older posts, perhaps with an up-to-date embellishment. This is a first effort…

Thoroughly approve! These stories have depth and if anyone wanted to they could continue to explore using your articles as the basis.

BTW. I’m glad you referred to me as a “longtime reader” as opposed to being an “old reader” 😉

Just like the Long-time Editor…

No mention of A P Herbert who lived along there? (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A._P._Herbert) ..the humorist, author, essayist and law-reformer?

No mention of that stretch along the Thames being known from the film ‘Sliding Doors’ ..just near the end; the scenes in the pub, and John Hannah sitting in a boat with Gwinny Paltrow, wasn’t it, drifting towards Hammersmith Bridge? ..now, sadly, closed to motor vehicle traffic as no council, nor government, can decide who’ll pay for its upkeep.

(..Lowest bridge on the Tidal Thames, incidentally, with only about 12′ between the water and its underside at High Water Springs!)

Thanks for the additional information, David. I’d forgotten the film reference and I seem to remember the area near the bridge is featured in another film… was it Dirk Bogarde in Victim? But it is a popular spot for TV locations, too.

I am a great admirer of A.P. Herbert, but I left him out because he lived on Hammersmith Terrace, which is away from The Dove. The only reason I brought in Hammersmith Terrace was because of Emery Walker and the association with the printing works. The house at No.1 still has a shop-style front, almost identical to The Doves Bindery next to Cobden-Sanderson’s home.

While we are in a reminiscing mood, readers will be interested in just one anecdote concerning A.P. Herbert. I’m sure you’ve heard it. The tale does that A.P.H. found himself in conflict with Hammersmith Council over a trifling bill which he resented paying. After protracted negotiations, he was told he had to pay up. So he wrote a cheque on the side of a pig and walked it to the old National Provincial Bank on King Street. Perfectly legal because he has stuck two-penny stamp on the unfortunate beast, and the bank had to stamp it as paid. No mention of defecation in the banking hall, but that would have been icing on the cake for A.P.H. I think he recounted this in “Punch” so it might have been rather embellished.

I was on holiday in France (1975?) and I’d been carrying around a letter from the Thames Conservancy reminding me to pay my boating licence, but had no cheque book with me.

So I stretched across and got a paper napkin, wrote the usual guff with my account and sort-code, the amount payable, signed it (nearly wrote “singed it”) and posted it off to Commodore Bridgeman at Molesey Lock.

The TC cashed it, and my permit was waiting for me on my arrival home a fortnight later.