Speeding things up improves life in countless ways — think of jet planes, bullet trains, and HOV lanes — but when it comes to cognitive decline, slowing things down is the name of the game. Let’s explore the subject of photography and brain health, and discover how to keep our minds as sharp as our focus.

It is an unwelcome but undeniable fact that working memory, executive functioning, and ability to process information decline with age for most of us; we are dealt a finite number of neurons at birth and with the passage of time they steadily pop their clogs, never to be replaced. But, there are concrete actions we can take to slow or minimise the decline.

Photography and brain health

Biomedical research is helping to identify them. Researchers are beginning to understand how behavioural choices impact brain health and have already demonstrated the beneficial link between exercise and cognitive ability; even the underlying biological processes responsible for these changes are becoming clearer. We may possess fewer neurons than when we were spry nineteen-year-olds, but the connections between them can be rewired and the entire neural network optimized, given the right stimuli.

Those of us in the Macfilos community have a powerful weapon in our armoury when it comes to fighting cognitive decline: our obsession with passion for photography.

I firmly believe photography engages our brains in ways that keep those neurons fighting fit. In this article, I outline ten ways photography is good for our brains.

Photography and brain health: benefit number one — walking to a location that affords a great view.

The payoff from forsaking your couch and hiking up a steep gradient to the top of a hill or along a winding path to a secluded beach is twofold: the photogenic vista that awaits you and the brain-health benefits of your exertion. It has been proven that walking significantly improves thinking ability, and what better companion for your stroll than a camera slung over your shoulder?

The best views are not always accessible by car; while some photographers might baulk at the journey on foot, it is good for our grey matter and good for our art. In fact, consider loading your camera bag with your heaviest gear — a Leica SL2 and collection of full-frame L-mount lenses would be ideal — giving you the added benefit of some weight training while you are at it.

Photography and brain health: benefit number two — using composition as a workout for our inferotemporal neurons

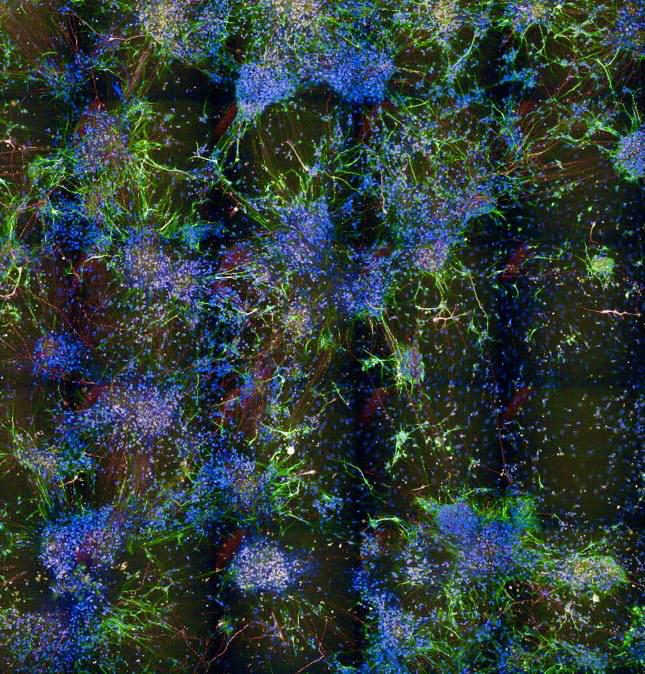

The world through your viewfinder comprises an assemblage of objects differing in shape and colour, some nearby, some distant. Regions in our brain devoted to visuospatial perception integrate and interpret this gemish of information, so we understand what we are seeing. Specialised neurons in the inferotemporal region of our visual cortex are summoned into action as we weigh how best to compose a photograph from the scene on our screen.

Should we zoom in on those shrubs in the mixed herbaceous border? Or should we highlight the alignment of shadows cast by that fence? Making these creative choices is the fun and challenge of photography, and for that spongy computer up top, like a session at the fitness centre.

Photography and brain health: benefit number three — harnessing our parieto-occipital neurons to capture the decisive moment

This second pathway within the visual cortex handles spatial location and motion of objects in the field of view. It comes in handy when driving a car or whacking a tennis ball. It is also busy when tracking the movement of a person, anticipating that moment when they are perfectly aligned with a reference point in the scene: a doorway or a gap between stepping stones in a pond.

This is the decisive moment, a term coined by Henri Cartier-Bresson, where a photographer has anticipated an important moment within the constant flow of life and captured it in a split second. I can almost feel my neurons go into overdrive and my noggin overheating as I track the subject’s trajectory, calculating when to press that shutter release. Give it a whirl; your brain will thank you.

Photography and brain health: benefit number four — employing hand-eye coordination to focus a camera manually

Just as there was a world of mental arithmetic, slide rules, and log tables before the advent of electronic calculators, a world of manually-focused cameras existed before the advent of autofocus. ‘Wait!’ I hear you protest, ‘manual focusing is still a thing, especially for Leica cameras’. It is indeed, and what an opportunity that affords. Accurately focusing a camera exercises neurons in the visual cortex and those governing fine motor control. So, let’s let them loose on some manual focusing challenges.

I confess that I have never used a rangefinder camera. Nevertheless, despite this egregious gap in my Leica journey, I do regularly focus my cameras manually. The physiological mechanics I employ are common to handling cameras in manual-focus mode: rotation of the focus ring on the lens barrel while viewing a scene through the viewfinder, judging by eye or focus-assist when the image is correctly focused.

This hand-eye-brain coordination is especially important with very fast lenses where the depth of field is razor-thin. Those neurons were really firing when a friend took this shot with his Fujifilm X-E4 and f/1.0 lens.

Photography and brain health: benefit number five — learning to use post-processing applications

Now that we have captured that cool image as a RAW file, it’s time to process, fine-tune, and export it as a JPEG, ready for submission to Macfilos. Here’s where a post-processing application such as Lightroom enters the scene and opens yet another avenue for improving brain health.

Before I splashed out on my Leica Q2, I had never heard of Lightroom; I had to figure out photo processing from scratch. Here was an opportunity to learn a new skill: a superb way to improve the brain’s neurocircuitry. In fact, it might be the best way to tune up that tangle of neurons housed in your head.

Even though some of us are getting long in the tooth, our brains are still plastic, meaning the spindly dendrites connecting our neurons to one another can be rearranged, forming new synapses that help us tackle new tasks. Practising our new skill also activates specialised brain cells called oligodendrocytes that strengthen the myelin sheaths insulating those dendrites, allowing electrical signals to flash along them more rapidly.

I am no Lightroom expert but am now reasonably proficient. I have even begun to use Photoshop to deal with blemishes or place borders on my abstract photos. As well as thousands of new photos, I reckon my Q2 purchase and Lightroom subscription have added millions of additional synapses to my collection; what a great deal!

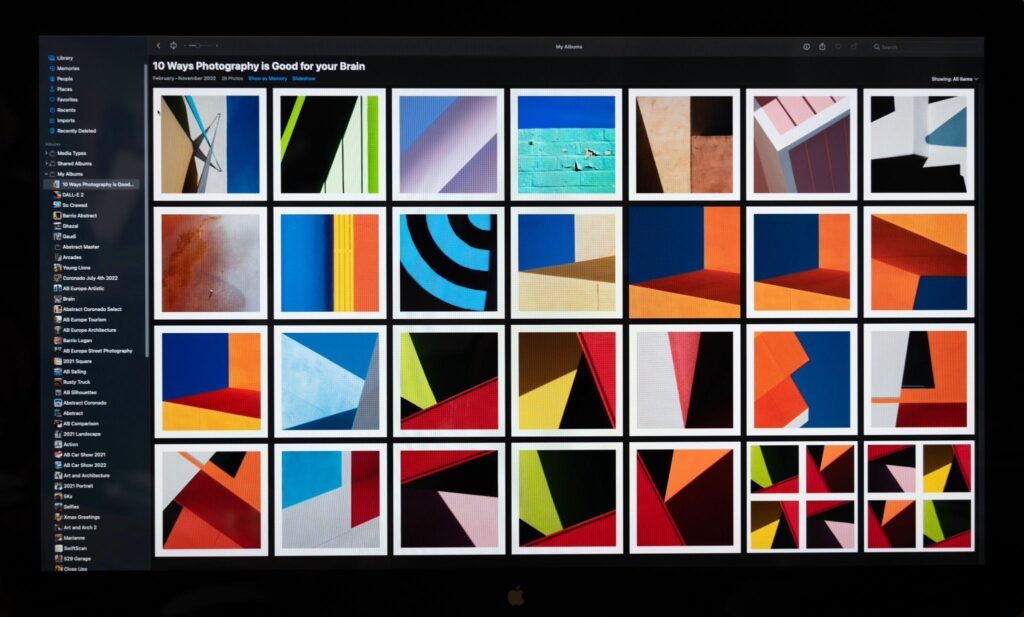

Photography and brain health: benefit number six — bringing order to that sprawling collection of photos.

If you are like me, your photographs live in many places: the cloud, accessible through applications such as Lightroom; the photo app on my computer; and as RAW files on a solid-state hard drive. How should I organize and harmonize these various collections? What logical archival framework would allow swift retrieval of images when needed for a new project? It could be based on chronology, location, topic, camera, lens, project or some other variable. So many choices! So many decisions! So good for the brain!

Solving multi-parametric puzzles like this, perhaps through folder-, album- or tag-based approaches, is good for keeping our cognitive capabilities sharp. And when the task is complete, we enjoy the extra benefit of a dopamine boost for our memory, motivation and concentration.

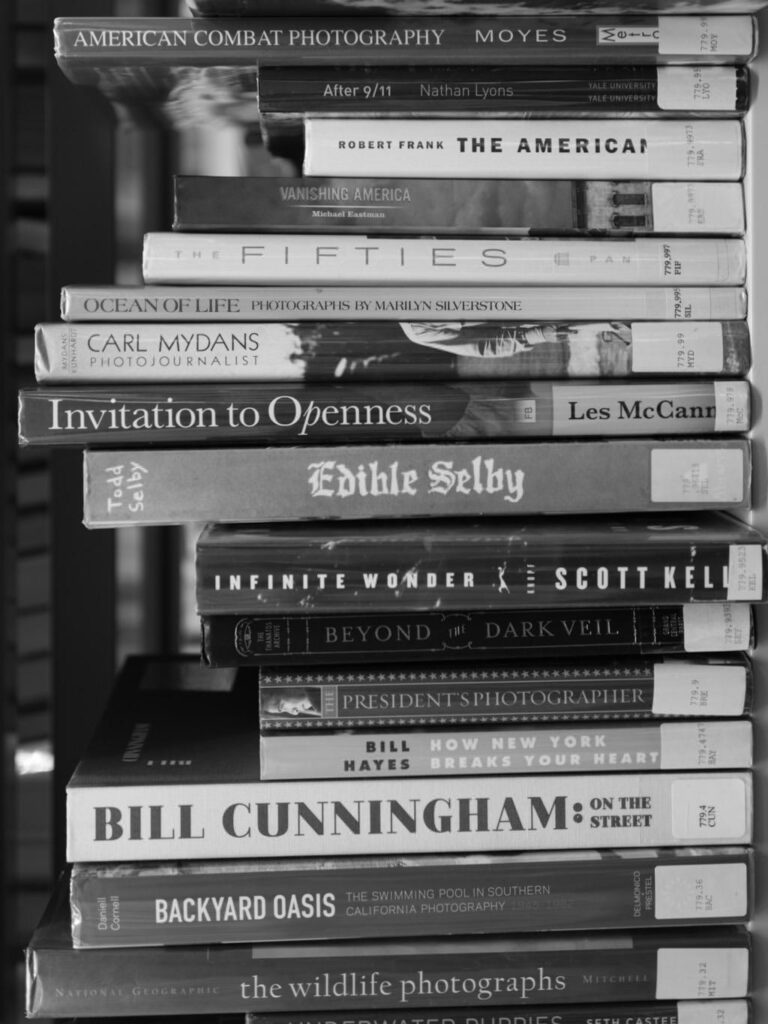

Photography and brain health: benefit number seven — reading books, articles, and blogs on photography

Here is another great way of taking your brain to the gym and working those mental muscles. Reading helps keep the mind active, and photography-related material exposes us to images that can lift our spirits and inspire us. There are so many aspects of photography to read about: technical details of cameras and lenses, reviews of the latest gear, reviews of vintage gear, biographies of photographers, travel stories, and opinion pieces.

Even though photography is primarily concerned with the visual arts, it is often complemented by a narrative describing the setting, the significance, and the creator of the photograph. Macfilos is a wonderful source of scholarly and informative articles about photography, and each article we consume adds heft to those reading muscles between our ears.

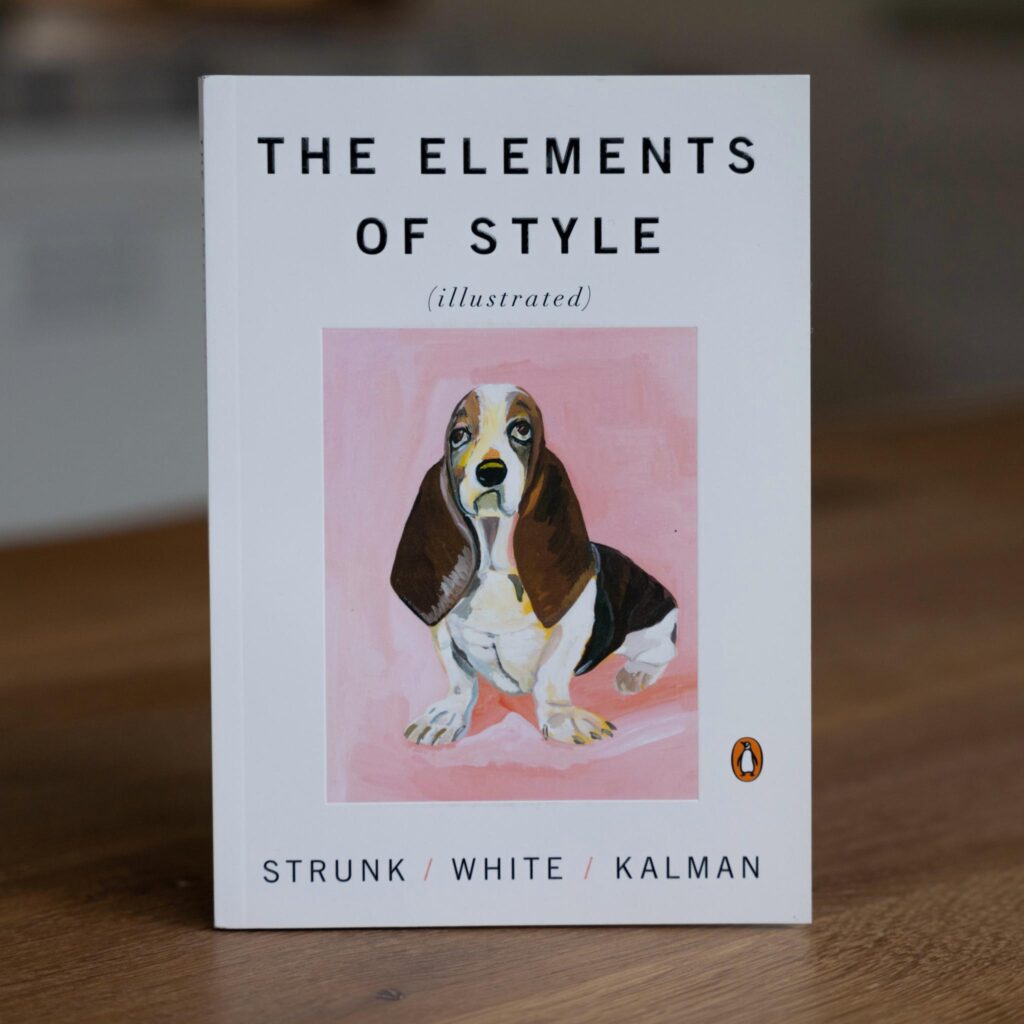

Photography and brain health: benefit number eight — writing about photography

As valuable as reading is for brain health, writing provides even more nourishment for our most energy-hungry organ. It demands the integration of multiple cognitive functions, including language, memory, and logic circuits, as well as hand-eye coordination and abstract thought. And that’s not even including the unique feature of writing about photography: tastefully illustrating articles with images likely created by the author.

Writing forces us to organize our thoughts; as we rack our brains for just the right words with which to convey them, we develop new neural circuitry along the way.

If you have yet to put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard to express your thoughts on photography, give it a go. I know just the person to whom you can send your article. Having recently encouraged a friend to write for Macfilos, I can testify how much he enjoyed the experience, we readers enjoyed the story, and his brain enjoyed the challenge.

Photography and brain health: benefit number nine — belonging to a community of photographers

Communities can be defined in many ways: through shared location, common background, or similar interests. One thing is clear, though: belonging to a community is a deeply-felt need and a powerful contributor to mental health. Although the world’s photographers could be considered a community linked by a common interest, a true sense of community is felt more emphatically by smaller groups who know and frequently communicate with each other in their distinctive patois.

Those interactions can be in person, through photography walks and social events, or virtually, through webinars and blog sites; they offer novice photographers an opportunity to learn, and experienced photographers an opportunity to share.

The Pacific Photography Society, based in San Diego, is an example of the former community, regularly organizing events hosted by experienced photographers. Macfilos is a great example of the virtual community, where, despite being distributed around the globe, we can schmooze and kvetch to our hearts’ content with people we have never met and perhaps will never meet.

In both cases, it falls to someone to take the initiative and organize these forums. They deserve credit for their leadership and contribution to improving our brains’ health.

Photography and brain health: benefit number ten — experiencing a regular dose of awe

By virtue of their relentless pursuit of breathtaking images, photographers are at increased risk of experiencing feelings of awe, an emotion proven to lift spirits, increase the width of grins, and boost psychological health. The photographers’ expanded view of the world, seen through lenses offering a field of view distinct from that of normal eyesight, increases the likelihood of them being awestruck – by a wide-angle shot of a cloudscape or a telephoto shot of an osprey plucking a hapless fish from the ocean.

Not only are photographers exposed to awesome experiences through their art, but they can also dole out awe to viewers of their photographs. After all, what greater compliment could a photographer receive than to have their work described as awe-inspiring?

Photographing natural wonders, spectacular buildings, or breathtaking sunsets is a surefire way to feel awe-inspired. I recently attended a virtual photography conference featuring a marine-wildlife photographer based in Monterey Bay, California. His work was truly awe-inspiring. Witnessing nature in all its beauty through his spectacular images lifted my spirits. That’s the power of awe.

Brains Trust

There are many more resources available to support healthy aging. Here’s one from The National Council on Aging. It is not specifically related to photography, but it is nevertheless a very helpful guide to keeping those neaurons in tip-top shape.

Have I convinced you of the link between photography and brain health? Is there someone you could encourage to take up photography and enjoy all these brain health benefits? Are you tempted to write about your experience as a photographer? Can you think of other ways that photography benefits our mental health? Please share your thoughts in the comments. I look forward to hearing from you.

Read more from the author

Join our community and play an active part in the future of Macfilos: This site is run by a group of volunteers and dedicated authors around the world. It is supported by donations from readers who appreciate a calm, stress-free experience, with courteous comments and an absence of advertising or commercialisation. Why not subscribe to the thrice-weekly newsletter by joining our mailing list? Comment on this article or, even, write your own. And if you have enjoyed the ride so far, please consider making a small donation to our ever-increasing running costs.

Great article Keith – I really enjoyed that.

all the best

Jono

Thanks Jono! Much appreciated. All the best, Keith

Hi Keith, this is another unconventional and fascinating contribution from you. Thank you very much!

I am sure that photography can help you to keep mental fitness, but I never managed to bring it down to a number or concrete points as you did. Sounds all very logical! The mixture of craftsmanship, technology, aesthetics, creativity and social exchange seems to work wonders. The same is said about the benefits of playing a musical instrument well into old age, for example piano. You have the same factors: Perception (in this case, hearing), brain (and heart)-hand-connection, aesthetic ideas, creative impetus, strive for perfection, communication (that’s what I think at least, never played the piano but love music). All in all: It seems to be important to have something that keeps you moving… Thanks again für this article. JP

And let’s not forget foreign languages or even a deeper understanding and ability with one’s native language. Even touch typing is a bit like playing the piano. Any skills such as these can help with keeping the brain cells busy.

Hi Joerg-Peter – many thanks! I was inspired to try my hand at a listicle by your listicle outlining gift ideas for photographers! That article also led me to buy a thumb grip for my Q2 – which is terrific. It was great fun brainstorming and researching the points I covered, drawing on a little on my science background. It was also the first time that I found myself taking photographs specifically for the purpose of illustrating an article.

The analogy you point out with learning and playing a musical instrument is spot on – another pursuit where the artist is hoping to inspire folk on the receiving end.

All the best!

Keith

Hi William – many thanks for your thoughts on this topic! I have some thoughts on ‘good for the body’, but ‘the mind’ and ‘the soul’ are too mysterious for me – well outside my jurisdiction! I think I will confine myself to considering the interaction of photography with flesh and blood matters. Having said that though, I suppose ‘awe’ might be on the borderline between a physical and a spiritual experience! All the best, Keith

When I’m out walking with herself, she often says “We have a long way to go, so there is no time for taking pictures”. My standard reply is ” When this walk is over, you’ll just have your memories, I’ll have my memories and my pictures”. To be fair she will often spot a great photographic opportunity which I will have missed and will draw it to my attention.

There are several stages of benefit in photography, but I will mention just three. Firstly there is actually activity of observing the world for potential photographs. This is a different way of observing the world than just going for a walk and admiring the scenery. It is also the reason why most photographers must always have a camera with them even if it just the one on a smartphone. The mental anguish of seeing a great scene and not being able to record it all is something much worse than actually having a camera and taking a bad photo.

Secondly, there are the whole series of activities surrounding the taking of the photo. The positioning, the choice of lens and camera settings, if these are available and then the capture of the image, including the sneaky peek at the rear screen if one is available on a digital model. Personally, I love the wait to see a developed film to see if it contains how I imagined the image of the scene.

The third stage is not only seeing the image for the first time, but also knowing that you can keep this forever, bringing yourself (and herself) back to a particular place and time. Often the ones which I took ‘against orders’ are the ones which are highly valued long afterwards.

‘Good for the mind, body and soul’ is how I would characterise photography.

William

Having settled in my seat for my daily dose of inspiration or education laid before me by Macfilos, I experienced the uncomfortable feeling of a college student who, by mischance or miscalculation, realized that he was sitting in the wrong lecture. As the student stirred to leave, the professor pleaded with him to stay. So he did and eventually left a much wiser and better-informed person.

I pride myself in my ambition to add a new word or two to my personal vocabulary as the opportunity arises. What a supreme challenge you have set me today!

Thank you for offering me the chance to explore the complex relationship between my brain and my photography. I am sure that I now have a much better insight into the relationship. I feel the benefit already.

Hi David – so pleased to read that the article expanded your vocabulary and provoked some reflection on the many ways photography engages and stimulates your brain. It might take a while before the opportunity arises to slip ‘oligodendrocyte’ or ‘inferotemporal neurons’ into a conversation, but it’s just a matter or time! All the best, Keith

Great brain exercise, thanks.

Manual activities involved in photography can also help to relax neurons: darkroom developing, alternative processing, pinhole camera development, or simply framing among others

Hi George – many thanks! Yes, these associated activities are both engaging and enriching. I can attest that framing a large-scale print of one’s photo and then standing back and admiring how neat it looks results in a very pleasant, dopamine-induced sensation! Cheers, Keith

Brilliant on many fronts – thank you!

This mirrors my behaviors since the start of Covid with almost daily walks with a camera to somewhere in the city and trying to see it fresh on each occasion.

Using LightRoom is also a fun way to see your work in multiple ways – there’s really no one way to present things. I recently went to the Chicago Art Institute to see the David Hockney exhibition “Spring in Normandy” and wondered whether you could get similar effects in LightRoom. Yes you can-ish. I’m a big fan of his as his “Wold Way” painted in Yorkshire, was my bike ride to grammar school in Bridlington a thousand years ago.

Seeing artists’ work is also good for the brain in terms of how they composed, used light and color. Gratefully the Art Institute is jammed full of great art for those bad weather days.

And finally learning how to use newly acquired camera equipment. This caused a lightbulb to flicker as I can now see a new way to convince “Management” that a new lens or camera is justified for my mental development.

Hi Le Chef – many thanks! I am a huge admirer of David Hockney’s art. I have enjoyed his work at every phase of his career – from early drawings and paintings of friends and family all the way through to his iPad work. I saw an extensive exhibition of his work at the Tate Britain some years ago, and it was wonderful to stand and stare at ‘Portraits of an artist’ and ‘A bigger splash’ in person.

I agree that learning to use new camera gear is another great brain workout, but it is clear from the pages of Macfilos that grappling with the complex menu systems employed by many camera brands is something many readers dislike and avoid. It seems Leica has a real edge in keeping it simple and avoiding too much brain strain! Cheers, Keith